Clement Reid FRS (6 January 1853 – 10 December 1916) was a British geologist and palaeobotanist.

Life edit

Reid was born in London in 1853. His great uncle was Michael Faraday. His family circumstances meant he was largely self-taught but he was nonetheless able to join the Geological Survey of Great Britain in 1874 and be employed in drawing up geological maps in various parts of the country. In 1894 he was appointed Geologist and in 1901 District Geologist. He retired in 1913.[1]

He was particularly concerned with tertiary geological deposits and their paleontology, and is most renowned for the work he did on quaternary and Pliocene deposits alongside his wife Eleanor in Norfolk.[2]

He was awarded The Murchison Fund in 1886, won the Bigsby Medal in 1897, was elected Fellow of the Geological Society in 1875, and was vice-president of the Geological Society of London 1913–1914. He was elected a Fellow of the Linnean Society in 1888.

In 1899 he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, his application citation reading:

Geologist in the Geological Survey of England and Wales, and has served on the Staff since 1874. Awarded the Murchison Fund by the Council of the Geological Society in 1886. Has been Secretary and Recorder to the Geological Section of the British Association. Has added largely to our knowledge of the Lower Tertiary formations of the Isle of Wight and Dorset, the Pliocene deposits of Norfolk and the North Downs (including the fauna and flora of the Cromer Forest Bed), and the Glacial Phenomena of Norfolk and Sussex. To aid his researches he has made a special study of recent and fossil seeds (a subject previously much neglected), whereby much light has been thrown on the climate conditions of later Tertiary times, and on the origin of the British flora. Author of Geological Survey memoirs on 'Geology of the Country around Cromer,' 1882; 'Geology of Holderness,' 1885; 'Pliocene Deposits of Britain,' 1890, and revised Tertiary portion of 'Geology of Isle of Wight,' 2nd ed, 1889. Also author of many original papers, including 'Dust and Soils' (Geol Mag, 1884); 'Norfolk Amber' (Trans Norf Nat Soc, 1884); 'Origin of Dry Chalk Valleys' (Quart Journ Geol Soc, 1887); 'Geological History of the Recent Flora of Britain' (Ann Botany, 1888); 'Pleistocene Deposits of Sussex Coast' (Quart Journ Geol Soc, 1892); 'Natural History of Isolated Ponds' (Trans Norf Nat Soc, 1892); 'Desert or Steppe Conditions in Britain' (Nat Science, 1893); 'Eocene Deposits of Dorset' (Quart Journ Geol Soc, 1896); 'Report on Relation of Palaeolithic Man to the Glacial Epoch' (Hoxne Excavation) (Brit Assoc, 1896)"[3]

From 1899 to 1909, Reid undertook the analysis of archaeobotanical remains from the Roman town of Silchester.[2]

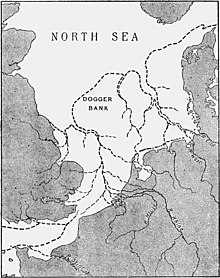

In 1913 he published his book "Submerged Forests" in which he postulated a drowned land bridge between eastern England and the European mainland. His conceptual map of what is now called "Doggerland" turned out to be remarkably close to the currently known reality.

He died in Milford-on-Sea, Hampshire in 1916. He had married in St Asaph in 1897 Eleanor Mary Wynne Edwards. She became a fellow herself and won the Lyell Medal for her work after Reid died.[4]

References edit

- ^ "Obituary - Clement Reid". Retrieved 11 January 2011.

- ^ a b Lodwick, L (2017). "'The debatable territory where geology and archaeology meet': reassessing the early archaeobotanical work of Clement Reid and Arthur Lyell at Roman Silchester" (PDF). Environmental Archaeology. 22 (1): 56–78. doi:10.1080/14614103.2015.1116218. S2CID 162420770.

- ^ "Library and Archive Catalogue". Royal Society. Retrieved 11 January 2011.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Marilyn Ogilvie; Joy Harvey (16 December 2003). The Biographical Dictionary of Women in Science: Pioneering Lives From Ancient Times to the Mid-20th Century. Routledge. pp. 385–386. ISBN 978-1-135-96343-9.

- Preece, R.C. & Killeen, I.J., 1995. Edward Forbes (1815-1854) and Clement Reid (1853-1916): two generations of pioneering polymaths. Archives of Natural History, 22: 419-435.

External links edit

- Works by or about Clement Reid at Wikisource

- Works by Clement Reid at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Chrono-Biographical Sketch: Clement Reid at www.wku.edu