Catherine Lynch (1880 – 19 October 1908), née Catherine Driscoll, also known as Kate Driscoll, was a petty criminal from Swansea, Wales. Following the death of her father in an industrial accident in 1900, Driscoll took up employment as a domestic servant to a local publican's family. She rapidly descended into crime and alcoholism, and over the next few years was regularly convicted of prostitution, theft, and alcohol-related public order offences. She married in 1906, becoming Catherine Lynch, and although her criminal activity appears to have fallen somewhat following her marriage she continued drinking heavily.

Catherine Lynch | |

|---|---|

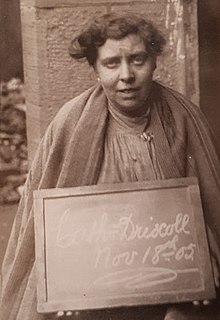

Catherine Driscoll (later Catherine Lynch) on admission to Swansea Prison, 18 November 1905, aged 25 | |

| Born | Catherine Driscoll 1880 Swansea, Wales |

| Died | 19 October 1908 (aged 27–28) Swansea, Wales |

| Nationality | Welsh |

| Other names | Kate Driscoll |

| Occupation(s) | Petty criminal, prostitute |

| Spouse | John Lynch (m.1906) |

In October 1908, at the age of 28, she collapsed and died at home while preparing to go out for the evening. A subsequent inquest attributed her death to a syncope induced by alcohol. The presiding coroner was harshly critical of her, describing her as "one of a class who were a nuisance to themselves, their husbands and everybody else" and as symptomatic of an increase in drunkenness among Swansea's women. He was also critical of her husband John Lynch for having continued to support her despite her alcoholism, instead of having taken the opportunity to have her incarcerated.

In her lifetime, Lynch attracted little notice beyond official records and local newspaper accounts. Her life was examined by local historian Elizabeth Belcham in her book Swansea's 'Bad Girls': Crime and Prostitution 1870s–1914.

Early life edit

Catherine Driscoll's father Jeremiah Driscoll had emigrated from County Cork to work in the Cwmfelin Tin Plate Works in Cwmbwrla.[1][2] He married Mary Ellen Sheehan in Swansea in 1876;[2] Catherine was born in Swansea in 1880, the third of the Driscolls' eight children.[2][3] A drunkard with a history of convictions for brawling and public drunkenness,[2][4] Jeremiah lived with his wife, children, parents and sister in a single house in Skinner Street, Swansea, later moving to a larger house in Baptist Well Street.[2]

Jeremiah Driscoll died due to an industrial accident on Monday May 7, 1900,[1] dying in hospital later that day.[5][3][1] Preparing to ride on a steam crane, he was waiting on the tracks of the crane as it approached, intending to sit on the crane's cab. He mistimed his sitting down, and sat in front of the oncoming crane.[6] The crane's driver, who was positioned at the rear of the crane, was unable to see Driscoll sitting on the tracks, and consequently did not stop. Jeremiah Driscoll sustained a crushed right foot, a broken spine, facial injuries and two broken ribs.[6] He was immediately taken to hospital but died shortly afterwards.[7] His injuries were described as "hopeless from the first",[6] and the coroner's jury ruled that his death was purely accidental.[1]

Adult life edit

With the family's breadwinner gone, Catherine, now commonly known as Kate, took a job as a domestic servant to a Swansea publican and his family in 1901.[2] She soon turned to crime; she first appeared in court charged with indecency in May 1903.[8][A] In June 1904, she was described in court for the first time as a prostitute;[10] her conviction on this occasion was for the public use of obscene language,[10] an offence for which she would be repeatedly prosecuted that year.[11]

By the following year, Driscoll was descending into alcoholism, and on 20 March 1905 she was sentenced to 14 days' hard labour following repeated convictions for being drunk and disorderly.[12][13] This did little to reduce her criminal activities; on 19 August 1905 she was again sentenced to 14 days' hard labour for "riotous behaviour in Castle-street".[14] On 17 November 1905 she was arrested, along with her friends Selina Rushbrook and Lily Argent,[15] for the theft of a sea captain's purse.[16][17][B] (By this time Driscoll had been convicted of indecency, obscene language, four counts of drunkenness and two counts of being a disorderly prostitute.[13][B]) Although all three were found not guilty on grounds of insufficient evidence,[19] days later Driscoll was convicted yet again of drunkenness, and sentenced to a month's imprisonment.[20][C]

The increasing severity of her sentences did not deter Driscoll; within days of her release from this sentence she was arrested yet again for riotous behaviour. The case against her was adjourned as she "pleaded that she was willing to go to St. Joseph's Convent".[21] She does not appear to have taken advantage of the leniency of the court; less than a month later, yet another charge of rioting was abandoned by the prosecutor "as she is now serving a term of imprisonment on another charge".[22] Following this sentence Driscoll appears to have evaded the attention of the authorities for a time, her sole court appearance being an allegation of the theft of £4 (about £460 in 2024 terms[9]) from a sailor with whom she had made a "promiscuous acquaintance", but she was released without charge when it transpired that she had no money on her at the time of her arrest.[23][D]

In August 1906 Kate Driscoll married John Lynch,[24] and settled with him at 96 Mitchell Row, Swansea.[25] Although she continued drinking,[24] she appears to have given up criminal activity for a time, and she did not come to the attention of the authorities for the remainder of 1906. This did not last; in May 1907 she was once again sentenced to a month's imprisonment, this time for the theft of a purse and four shillings (about £20 in 2024 terms[9]).[26]

John and Catherine Lynch subsequently moved to 6 Michael's Row in the Greenhill district of central Swansea.[27] Catherine Lynch's descent into alcoholism and crime continued, and in June 1908 she yet again was prosecuted, on this occasion for the theft of three half-crowns (about £40 in 2024 terms[9]) from a coal miner who had been "in the woman's company".[28] (Lynch denied being with him, telling the court that "I don't go with a dirty little scamp like that".[29]) It was noted that Lynch by now had 41 previous convictions, and she was sentenced to two months' imprisonment.[28][B]

Death edit

On the evening of 19 October 1908, aged 28, Catherine Lynch was "preparing to go out to a place of amusement".[27] She was washing her face and hands in her Michael's Row home, when she went to sit on the stairs. At 7.15 p.m. she suddenly fell backwards. John Lynch tried to give her a drink of water but she was unable to drink it; he carried her upstairs to bed, and summoned a doctor.[27] Upon Dr Jones Powell's arrival he found her dead in bed.[27] Jones Powell attributed her death to syncope (fainting) induced by alcoholism.[27]

At the coroner's inquest, John Lynch testified that Catherine had been drunk at the time. Challenged by the coroner as to why he had allowed her to drink herself into such a condition, John stated that she had been an alcoholic for as long as he had known her, and that he felt obliged to give her money for drink as "if I didn't she used to take it off me".[27] Mr. Leeder, the coroner, challenged John Lynch, advising him that he should have contacted the police and have her "put away", stating that this would have been "cheaper than allowing her to ruin the home".[27] Leeder was unsympathetic to Catherine Lynch, describing her as "one of a class who were a nuisance to themselves, their husbands and everybody else".[27] He considered Lynch's death as part of a pattern of increasing drunkenness among women in Swansea,[30] observing that "one woman led others to drink, for she would not drink by herself"[31] and "when one of these women went wrong she dragged six others with her".[27] In line with Jones Powell's testimony, the jury returned a verdict of "death from syncope brought on by excessive drinking".[30] She was buried in Danygraig Cemetery on 23 October 1908.[24][E]

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ For this first conviction, Driscoll was given the choice of paying a fine of £1 4s (about £140 in 2024 terms[9]) or 14 days' imprisonment.[8]

- ^ a b c As with all Swansea prostitutes in this period, her number of convictions for theft is misleadingly low. Prostitutes doing business with sailors would enquire as to when they were sailing out, and if the customer's ship was due to sail soon would attempt to steal their money, in the knowledge that by the time they appeared in court the victim would no longer be available to give evidence. As sailors were paid back-pay for their time at sea once on shore, they often had large quantities of cash on them, little to spend it on, little knowledge of the city, and often took the opportunity of shore leave to get drunk, making them ideal targets for prostitutes and thieves.[18]

- ^ Ebenezer Rushbrook, husband of Driscoll's accomplice Selina Rushbrook, was also convicted of drunkenness at the same hearing.[20]

- ^ By this time Driscoll was a familiar face in the local courts; when she said "I am innocent, gentlemen" following her release, she was warned by the Court Clerk "You had better not protest too much".[23]

- ^ She was buried in Board grave 31932 409/O in Danygraig Cemetery, under the name Catherine Driscoll Lynch.[32]

References edit

- ^ a b c d "Local News". The Cambrian. Swansea. 11 May 1900. p. 5.

On Wednesday afternoon, before the Deputy Coroner (Mr. Talfourd Strick), an inquest was held at the Hospital on the body of Jeremiah Driscoll, an employee of the Cwmfelin Works Co., who succumbed to injuries sustained on Monday morning whilst at work.

- ^ a b c d e f Belcham 2016, p. 337.

- ^ a b "Local News Items". Evening Express. Cardiff. 8 May 1900. p. 4.

- ^ "Swansea Police Court". The Cambrian. Swansea. 29 March 1889. p. 8.

- ^ "Jeremiah Driscoll - Died: 7 May 1900". billiongraves.com. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ a b c "Cwmfelin Works Fatality". South Wales Daily Post. Swansea. 9 May 1900. p. 4.

- ^ "Local News Paragraphs". Western Mail. Cardiff. 8 May 1900. p. 6.

- ^ a b Belcham 2016, pp. 337–338.

- ^ a b c d UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Obscene Language". The Cambrian. Swansea. 24 June 1904. p. 8.

- ^ "Coun. Morgan Hopkin Prosecutes". The Cambrian. Swansea. 14 October 1904. p. 3.

- ^ Belcham 2016, p. 325.

- ^ a b Belcham 2016, p. 338.

- ^ "Swansea Police Court". The Cambrian. Swansea. 25 August 1905. p. 2.

- ^ Belcham 2016, p. 35.

- ^ "Sea Captain's Adventure: Swansea Women at the Assizes". Evening Express. Cardiff: Walter Alfred Pearce. 23 November 1905. p. 3.

- ^ Belcham 2016, p. 151.

- ^ Belcham 2016, p. 286.

- ^ "Skipper's Adventure on the Strand". The Cambrian. Swansea. 24 November 1905. p. 5.

- ^ a b "Drunk and Riotous". The Cambrian. Swansea. 8 December 1905. p. 8.

- ^ "Swansea Police Court". The Cambrian. Swansea. 12 January 1906. p. 6.

- ^ "Under Lock and Key". The Cambrian. Swansea. 9 February 1906. p. 6.

- ^ a b "Advice to an Ex-Prisoner". Evening Express. Cardiff. 30 June 1906. p. 2.

- ^ a b c Belcham 2016, p. 339.

- ^ "News in Brief". Evening Express. Cardiff. 20 May 1907. p. 3.

- ^ "Justices in Holiday Mood". The Cardiff Times. Cardiff. 25 May 1907. p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "About to go Out for the Evening". The Cambrian. Swansea. 23 October 1908. p. 6.

- ^ a b "Maesteg Collier's Adventure". The Glamorgan Gazette. Bridgend. 19 June 1908. p. 7.

- ^ "Willing to "Swing for Him."". Weekly Mail. Cardiff. 20 June 1908. p. 10.

- ^ a b "Drinking Habits of Women: Coroner's Pointed Remarks at Swansea". Evening Express. Cardiff. 21 October 1908. p. 3.

- ^ "Drank Herself to Death". The Cardiff Times. Cardiff. 24 October 1908. p. 12.

- ^ Belcham 2016, p. 397.

Bibliography edit

- Belcham, Elizabeth F. (2016). Swansea's 'Bad Girls': Crime and Prostitution 1870s–1914. Glynneath: Heritage Add-Ventures. ISBN 978-0-9575974-2-6.