Stoning, or lapidation, is a method of capital punishment where a group throws stones at a person until the subject dies from blunt trauma. It has been attested as a form of punishment for grave misdeeds since ancient times.

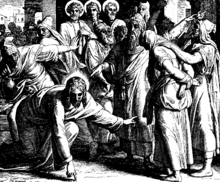

(Pinakothek of Munich)

Stoning appears to have been the standard method of capital punishment in ancient Israel. Its use is attested in the early Christian era, but Jewish courts generally avoided stoning sentences in later times. Only a few isolated instances of legal stoning are recorded in pre-modern history of the Islamic world. Criminal laws of most modern Muslim-majority countries have been derived from Western models. In recent decades several states have inserted stoning and other hudud (pl. of hadd) punishments into their penal codes under the influence of Islamist movements. These laws hold particular importance for religious conservatives due to their scriptural origin, though in practice they have played a largely symbolic role and tended to fall into disuse.

The Torah and Talmud prescribe stoning as punishment for a number of offenses. Over the centuries, Rabbinic Judaism developed a number of procedural constraints which made these laws practically unenforceable. Although stoning is not mentioned in the Quran, classical Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh) imposed stoning as a hadd (sharia-prescribed) punishment for certain forms of zina (illicit sexual intercourse) on the basis of hadith (sayings and actions attributed to the Islamic prophet Muhammad). It also developed a number of procedural requirements which made zina difficult to prove in practice.

In recent times, stoning has been a legal or customary punishment in Iran, United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Yemen, northern Nigeria, Afghanistan, Brunei, and tribal parts of Pakistan, including northwest Kurram Valley and the northwest Khwezai-Baezai region though it is rarely carried out.[1][2][3][4] In some of these countries, including Afghanistan, it has been carried out extrajudicially by militants, tribal leaders, and others.[2] In some other countries, including Nigeria and Pakistan, although stoning is a legal form of punishment, it has never been legally carried out. Stoning is condemned by human rights organizations.

History

Stoning is attested in the Near East since ancient times as a form of capital punishment for grave sins.[5] However stoning as a practice was not geographically limited to only the Near East, and there is significant historical record of stoning being employed in the west as well. The ancient geographer Pausanias describes both the elder and younger Aristocrates of Orchomenus being stoned to death in ancient Greece around the 7th century BCE.

Stoning was "presumably" the standard form of capital punishment in ancient Israel.[6] It is attested in the Old Testament as a punishment for blasphemy, idolatry and other crimes, in which the entire community pelted the offender with stones outside a city.[7] The death of Stephen, as reported in the New Testament (Acts 7:58) was also organized in this way. Paul was stoned and left for dead in Lystra (Acts 14:19). Josephus and Eusebius report that Pharisees stoned James, brother of Jesus, after hurling him from the pinnacle of the Temple shortly before the fall of Jerusalem in 70 CE. Historians disagree as to whether Roman authorities allowed Jewish communities to apply capital punishment to those who broke religious laws, or whether these episodes represented a form of lynching.[7] During the Late Antiquity, the tendency of not applying the death penalty at all became predominant in Jewish courts.[8] Where medieval Jewish courts had the power to pass and execute death sentences, they continued to do so for particularly grave offenses, although not necessarily the ones defined by the law, and they generally refrained from use of stoning.[6]

Aside from "a few rare and isolated" instances from the pre-modern era and several recent cases, there is no historical record of stoning for zina being legally carried out in the Islamic world.[9] In the modern era, sharia-based criminal laws have been widely replaced by statutes inspired by European models.[10][11] However, the Islamic revival of the late 20th century brought along the emergence of Islamist movements calling for full implementation of sharia, including reinstatement of stoning and other hudud punishments.[10][12] A number of factors have contributed to the rise of these movements, including the failure of authoritarian secular regimes to meet the expectations of their citizens, and a desire of Muslim populations to return to more culturally authentic forms of socio-political organization in the face of a perceived cultural invasion from the West.[13][14] Supporters of sharia-based legal reforms felt that "Western law" had its chance to bring development and justice, and hoped that a return to Islamic law would produce better results. They also hoped that introduction of harsh penalties would put an end to crime and social problems.[15]

In practice, Islamization campaigns have focused on a few highly visible issues associated with the conservative Muslim identity, particularly women's hijab and the hudud criminal punishments (whipping, stoning and amputation) prescribed for certain crimes.[13] For many Islamists, hudud punishments are at the core of the divine sharia because they are specified by the letter of scripture rather than by human interpreters. Modern Islamists have often rejected, at least in theory, the stringent procedural constraints developed by classical jurists to restrict their application.[10] Several countries, including Iran, Pakistan, Sudan, and some Nigerian states have incorporated hudud rules into their criminal justice systems, which, however, retained fundamental influences of earlier Westernizing reforms.[10][12] In practice, these changes were largely symbolic, and aside from some cases brought to trial to demonstrate that the new rules were being enforced, hudud punishments tended to fall into disuse, sometimes to be revived depending on the local political climate.[10][11] The supreme courts of Sudan and Iran have rarely approved verdicts of stoning or amputation, and the supreme courts of Pakistan and Nigeria have never done so.[11]

Unlike other countries, where stoning was introduced into state law as part of recent reforms, Saudi Arabia has never adopted a criminal code and Saudi judges still follow traditional Hanbali jurisprudence.[16] Death sentences in Saudi Arabia are pronounced almost exclusively based on the system of judicial sentencing discretion (tazir) rather than sharia-prescribed (hudud) punishments, following the classical principle that hudud penalties should be avoided if possible.[17]

In China, stoning was one of the many methods of killing carried out during the Cultural Revolution, including the Guangxi Massacre.[18]

Religious scripture and law

Judaism

Torah

The Jewish Torah (the first five books of the Hebrew Bible: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) serves as a common religious reference for Judaism. Stoning is the method of execution mentioned most frequently in the Torah. (Murder is not mentioned as an offense punishable by stoning, but it seems that a member of the victim's family was allowed to kill the murderer; see avenger of blood.)

Mishna

Mode of judgment

In rabbinic law, capital punishment may be inflicted by only the verdict of a regularly constituted court of twenty-three qualified members. There must be the most trustworthy and convincing testimony of at least two qualified eyewitnesses to the crime, who must also depose that the culprit had been forewarned of the criminality and the consequences of such a project.[19] The culprit must be a person of legal age and of sound mind, and the crime must be proved to have been committed of the culprit's free will and without the aid of others.

Islam

Islamic sharia law is based on the Quran and the hadith as primary sources.

Quran

Stoning is not mentioned as a form of capital punishment in the canonical text of the Quran. However, Islamic scholars have traditionally postulated that there is a Quranic verse ("If a man or a woman commits adultery, stone them...") which was "abrogated" textually while retaining its legal force.[20]

Hadith

Stoning in the Sunnah mainly follows on the Jewish stoning rules of the Torah.[citation needed]

Contemporary legal status and use

As of September 2010, stoning is a punishment that is included in the laws in some countries including Saudi Arabia, Sudan, Iran, Somalia, Yemen and some predominantly Muslim states in northern Nigeria as punishment for Zina ("adultery by married persons").[21][22][23]

Afghanistan

Before the Taliban government, most areas of Afghanistan, aside from the capital, Kabul, were controlled by warlords or tribal leaders. The Afghan legal system depended highly on an individual community's local culture and the political or religious ideology of its leaders. Stoning also occurred in lawless areas, where vigilantes committed the act for political purposes. Once the Taliban took over in 1996, it became a form of punishment for certain serious crimes or adultery.[24][25][26][27] After the fall of the Taliban government, the Karzai administration re-enforced the 1976 penal code which made no provision for the use of stoning as a punishment. In 2013, the Ministry of Justice proposed public stoning as punishment for adultery.[28] However, the government had to back down from the proposal after it was leaked and triggered international outcry.[25]

After the Taliban took back power in 2021, stoning became legal again.[29][30][31][32]

Brunei

Per a penal code announced by the government of Brunei on 3 April 2019, any Muslim individuals found guilty of gay sex and adultery are stoned to death, and the punishment must be "witnessed by a group of Muslims."[33] In the adoption of this law, Brunei became the first Southeast Asian country to officially allow public stoning as a judicial form of punishment.

On 5 May 2019, the Sultan of Brunei confirmed that the de facto moratorium (a delay or suspension of an activity or a law) on the death penalty applied to the Sharia Penal Code, and committed Brunei to ratifying the United Nations Convention Against Torture (UNCAT).

Iran

The Iranian judiciary officially placed a moratorium on stoning in 2002; however, in 2007, the Iranian judiciary confirmed that a man who had been convicted of adultery 10 years earlier, was stoned to death in Qazvin province.[34] In 2008, the judiciary tried to eliminate the punishment from the books in legislation submitted to parliament for approval.[35] In 2009, two people were stoned to death in Mashhad, Razavi Khorasan Province as punishment for the crime of adultery.[36] The amended penal code, adopted in 2013, no longer contains explicit language prescribing stoning as punishment for adultery. According to legal experts, while an explicit prescription of stoning as punishment for adultery has been removed from Iran's new penal code, stoning remains a possible form of punishment, since the penal code still lists it, without specifying when it should be used, and allows punishment to be based on fiqh (traditional Islamic jurisprudence), which includes provisions for stoning.[37][38] In 2013 the spokesman for the Iranian Parliament's Justice Commission confirmed that while the Penal Code no longer prescribes stoning, it remains a valid punishment under sharia, which is enforceable under the Penal Code.[37][39] The most known case in Iran was the stoning of Soraya Manutchehri in 1986.

- Methods

In the 2008 version of the Islamic Penal Code of Iran detailed how stoning punishments are to be carried out for adultery, and even hints in some contexts that the punishment may allow for its victims to avoid death:[40]

Article 102 – An adulterous man shall be buried in a ditch up to near his waist and an adulterous woman up to near her chest and then stoned to death.

Article 103 – In case the person sentenced to stoning escapes the ditch in which they are buried, then if the adultery is proven by testimony then they will be returned for the punishment but if it is proven by their own confession then they will not be returned.[40]

Article 104 – The size of the stone used in stoning shall not be too large to kill the convict by one or two throws and at the same time shall not be too small to be called a stone.[40]

Depending upon the details of the case, the stoning may be initiated by the judge overseeing the matter or by one of the original witnesses to the adultery.[40] Certain religious procedures may also need to be followed both before and after the implementation of a stoning execution, such as wrapping the person being stoned in traditional burial dress before the procedure.[41]

The method of stoning set out in the 2008 code was similar to that in a 1999 version of Iran's penal code.[42] Iran revised its penal code in 2013. The new code does not include the above passages, but does include stoning as a hadd punishment.[38] For example, Book I, Part III, Chapter 5, Article 132 of the new Islamic Penal Code (IPC) of 2013 in the Islamic Republic of Iran states, "If a man and a woman commit zina together more than one time, if the death penalty and flogging or stoning and flogging are imposed, only the death penalty or stoning, whichever is applicable, shall be executed".[43] Book 2, Part II, Chapter 1, Article 225 of the Iran's IPC released in 2013 states, "the hadd punishment for zina of a man and a woman who meet the conditions of ihsan shall be stoning to death".[43][44]

Indonesia

On 14 September 2009, the outgoing Aceh Legislative Council passed a bylaw that called for the stoning of married adulterers.[45] However, then governor Irwandi Yusuf refused to sign the bylaw, thereby keeping it a law without legal force and, in some views, therefore still a law draft, rather than actual law.[46] In March 2013, the Aceh government removed the stoning provision from its own draft of a new criminal code.[47]

Iraq

In 2007, Du'a Khalil Aswad, a Yazidi girl, was stoned by her fellow tribesmen in northern Iraq for dating a Muslim boy.[48]

In 2012 at least 14 youths were stoned to death in Baghdad, apparently as part of a Shi'ite militant campaign against Western-style "emo" fashion. It was followed by condemnation by Shiite scholars.[49]

An Iraqi man was stoned to death by IS, in August 2014, in the northern city of Mosul after one Sunni Islamic court sentenced him to die for the crime of adultery.[50]

Nigeria

Since the sharia legal system was introduced in the predominantly Muslim north of Nigeria in 2000, more than a dozen Nigerian Muslims have been sentenced to death by stoning for sexual offences ranging from adultery to homosexuality. However, none of these sentences have actually been carried out. They have either been thrown out on appeal, commuted to prison terms or left unenforced, in part as a result of pressure from human rights groups.[51][52][53][54]

Pakistan

As part of Zia-ul-Haq's Islamization measures, stoning to death (rajm) at a public place was introduced into law via the 1979 Hudood Ordinances as punishment for adultery (zina) and rape (zina-bil-jabr) when committed by a married person.[55] However, stoning has never been officially utilized since the law came into effect and all judicial executions occur by hanging.[56] The first conviction and sentence of stoning (of Fehmida and Allah-Bakhsh) in September 1981 was overturned under national and international pressure. Another conviction for adultery and sentence of stoning (of Shahida Parveen and Muhammad Sarwar) in early 1988 sparked outrage and led to a retrial and acquittal by the Federal Sharia Court. In this case the trial court took the view that notice of divorce by Shahida's former husband, Khushi Muhammad, should have been given to the Chairman of the local council, as stipulated under Section-7(3) of the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance, 1961. This section states that any man who divorces his wife must register it with the Union Council. Otherwise, the court concluded that the divorce stood invalidated and the couple became liable to conviction under the Adultery ordinance. In 2006, the ordinances providing for stoning in the case of adultery or rape were legislatively demoted from overriding status.[57]

Extrajudicial stonings in Pakistan have been known to happen in recent times. In March 2013, Pakistani soldier Anwar Din, stationed in Parachinar, was publicly stoned to death for allegedly having a love affair with a girl from a village in the country's north western Kurram Agency.[58] On 11 July 2013, Arifa Bibi, a young mother of two, was sentenced by a tribal court in Dera Ghazi Khan District, in Punjab, to be stoned to death for possessing a cell phone. Members of her family were ordered to execute her sentence and her body was buried in the desert far away from her village.[2][59]

In February 2014, a couple in a remote area of Baluchistan province was stoned to death after being accused of an adulterous relationship.[60] On 27 May 2014, Farzana Parveen, a 25-year-old married woman who was three months pregnant, was killed by being attacked with batons and bricks by nearly 20 members of her family outside the high court of Lahore in front of "a crowd of onlookers" according to a statement by a police investigator. The assailants, who allegedly included her father and brothers, attacked Farzana and her husband Mohammad Iqbal with batons and bricks. Her father Mohammad Azeem, who was arrested for murder, reportedly called the murder an "honor killing" and said "I killed my daughter as she had insulted all of our family by marrying a man without our consent."[61] The man whose second wife Farzana had become, Iqbal, told a news agency that he had strangled his previous wife in order to marry Farzana, and police said that he had been released for killing his first wife because a "compromise" had been reached with his family.[62]

Saudi Arabia

Legal stoning sentences have been reported in Saudi Arabia.[63][64] There were four cases of execution by stoning reported between 1981 and 1992, but nothing since.[65]

Sudan

In May 2012, a Sudanese court convicted Intisar Sharif Abdallah of adultery and sentenced her to death; the charges were appealed and dropped two months later.[66] In July 2012, a criminal court in Khartoum, Sudan, sentenced 23-year-old Layla Ibrahim Issa Jumul to death by stoning for adultery.[67] Amnesty International reported that she was denied legal counsel during the trial and was convicted only on the basis of her confession. The organization designated her a prisoner of conscience, "held in detention solely for consensual sexual relations", and lobbied for her release.[66] In September, Article 126 of the 1991 Sudan Criminal Law, which provided for death by stoning for apostasy, was amended to provide for death by hanging.[citation needed]

In June 2022, Sudan sentenced a woman named Maryam Alsyed Tiyrab, to death by stoning, although the previous year it had ratified the UN Convention Against Torture which forbids the practice.[68]

Somalia

In October 2008, a 13-year-old girl, Aisha Ibrahim Duhulow, reported being gang-raped by three armed men to the local al-Shabaab militia-dominated police force in Kismayo, a city that was controlled Islamist insurgents.[69] The insurgents claimed that Aisha had committed adultery by seducing the men, and went on to allege that she was 23 years of age (a claim disproven by both Aisha's father and aunt) and that she had expressly stated she wanted sharia law to be applied in her sentencing, thus theoretically justifying the capital punishment of stoning.[70] However, numerous witnesses have reported that in actuality Aisha had been visibly confused, crying, begging for mercy, and was physically forced into the hole in which she was buried up to her neck and stoned.[71]

In September 2014, al-Shabaab militants stoned a woman to death, after she was declared guilty of adultery by an informal court.[72]

United Arab Emirates

Since 2020, stoning is no longer a legal form of punishment following an amendment to the Federal Penal Code.[73] Before 2020, stoning was the default method of execution for adultery and homosexuality. Article 354 of the Federal Penal Code states: "Whoever commits rape on a female or sodomy with a male shall be punished by death.",[74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][excessive citations].,[83] and several people were sentenced to death by stoning.[84][85][86][87]

Islamic State

Several adultery executions by stoning committed by IS were reported in the autumn of 2014.[88][89][90] The Islamic State's magazine, Dabiq, documented the stoning of a woman in Raqqa as a punishment for adultery.[citation needed]

In October 2014, IS released a video appearing to show a Syrian man stone his daughter to death for alleged adultery.[90][91]

Other countries

Isolated incidents of illegal stoning also occur in countries where the practice is not generally a customary punishment. Stonings have been reported in Mexico in 2009,[92][93] 2010[94] 2011[95] and 2023.[96] In 1934, two Mexican women were stoned to death by a mob on the ground that they visited Puebla to make Socialist speeches.[97] In Guatemala, mob lynching has become a common form of vigilante justice, and is considered a legacy of the civil war.[98][99][100] In 2000, in the Guatemalan town of Todos Santos Cuchumatán, a bus driver and a Japanese tourist were stoned to death by a mob due to rumors that foreign tourists intend to kidnap Guatemalan children.[101] In 2021, a mob of more than 600 villagers in Honduras accused an Italian tourist of murdering a homeless man and stoned him to death.[102]

Views

Support

Among Christians

The late American Calvinist and Christian Reconstructionist cleric Rousas John (R. J.) Rushdoony, his son Mark and his son-in-law Gary North, supported the reinstatement of the Mosaic law's penal sanctions. Under such a system, the list of civil crimes which carried a death sentence by stoning would include homosexuality, adultery, incest, lying about one's virginity, bestiality, witchcraft, idolatry or apostasy, public blasphemy, false prophesying, kidnapping, rape, and bearing false witness in a capital case.[103][104][105][106]

Among Muslims

A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center in 2013 found varying support in the global Muslim population for stoning as a punishment for adultery (sex between people where at least one person is married; when both participants are unmarried they get 100 lashes). Highest support for stoning is found in Muslims of the Middle East-North Africa region and South-Asian countries while generally less support is found in Muslims living in the Mediterranean and Central Asian countries. Support is consistently higher in Muslims who want Sharia to be the law of the land than in Muslims who do not want Sharia.[107] Support for stoning in various countries is as follows:

South Asia:

Pakistan (86% in all Muslims, 89% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land), Afghanistan (84% in all Muslims, 85% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land), Bangladesh (54% in all Muslims, 55% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land)[107][108]

Middle East-North Africa:

Palestinian territories (81% in all Muslims, 84% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land), Egypt (80% in all Muslims, 81% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land), Jordan (65% in all Muslims, 67% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land), Iraq (57% in all Muslims, 58% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land)[107][108]

Southeast Asia:

Malaysia (54% in all Muslims, 60% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land), Indonesia (42% in all Muslims, 48% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land), Thailand (44% in all Muslims, 51% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land)[107][108]

Sub-Saharan Africa:

Niger (70% in all Muslims), Djibouti (67%), Mali (58%), Senegal (58%), Guinea Bissau (54%), Tanzania (45%), Ghana (42%), DR Congo (39%), Cameroon (36%), Nigeria (33%)[107][108]

Central Asia:

Kyrgyzstan (26% in all Muslims, 39% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land), Tajikistan (25% in all Muslims, 51% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land), Azerbaijan (16%), Turkey (9% in all Muslims, 29% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land)[107][108]

Southern and Eastern Europe:

Russia (13% in all Muslims, 26% in Muslims who say sharia should be the law of the land), Kosovo (9% in all Muslims, 25% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land), Albania (6% in all Muslims, 25% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land), Bosnia (6% in all Muslims, 21% in Muslims who say Sharia should be the law of the land)[107][108]

Places where substantial numbers of Muslims did not answer the survey's question or are undecided about whether they support stoning for adultery include Malaysia (19% of all Muslims), Kosovo (18%), Iraq (14%), Democratic Republic of the Congo (12%) and Tajikistan (10%).[108]

Opposition

Stoning has been condemned by several human rights organizations. Some groups, such as Amnesty International[109] and Human Rights Watch, oppose all capital punishment, including stoning. Other groups, such as RAWA (Revolutionary Association of the Women of Afghanistan), or the International Committee against Stoning (ICAS), oppose stoning per se as an especially cruel practice.

Specific sentences of stoning, such as the Amina Lawal case, have often generated international protest. Groups such as Human Rights Watch,[110] while in sympathy with these protests, have raised a concern that the Western focus on stoning as an especially "exotic" or "barbaric" act distracts from what they view as the larger problems of capital punishment. They argue that the "more fundamental human rights issue in Nigeria is the dysfunctional justice system."

In Iran, the Stop Stoning Forever Campaign was formed by various women's rights activists after a man and a woman were stoned to death in Mashhad in May 2006. The campaign's main goal is to legally abolish stoning as a form of punishment for adultery in Iran.[111]

Human rights

Stoning is condemned by human rights groups as a form of cruel and unusual punishment and torture, and a serious violation of human rights.[112][113]

Women's rights

Stoning has been condemned as a violation of women's rights and a form of discrimination against women. Although stoning is also applied to men, the vast majority of the victims are reported to be women.[114][115][116] According to the international group Women Living Under Muslim Laws stoning "is one of the most brutal forms of violence perpetrated against women in order to control and punish their sexuality and basic freedoms".[117]

Amnesty International has argued that the reasons for which women suffer disproportionately from stoning include the fact that women are not treated equally and fairly by the courts; the fact that, being more likely to be illiterate than men, women are more likely to sign confessions to crimes which they did not commit; and the fact that general discrimination against women in other life aspects leaves them at higher risk of convictions for adultery.[118]

LGBT rights

Stoning also targets homosexuals and others who have same-sex relations in certain jurisdictions. In Mauritania,[1] Northern Nigeria,[119] Somalia,[1] Saudi Arabia,[120] Brunei,[33] and Yemen,[1] the legal punishment for sodomy is death by stoning.

Right to private life

Human rights organizations argue that many acts targeted by stoning should not be illegal in the first place, as outlawing them interferes with people's right to a private life. Amnesty International said that stoning deals with "acts which should never be criminalized in the first place, including consensual sexual relations between adults, and choosing one's religion".[112]

Examples

Ancient

- Palamedes of Greek mythology, according to some sources stoned to death as a traitor.

- Lucius Appuleius Saturninus, d. 100 BC, grandfather of later triumvir Marcus Aemilius Lepidus

- Pancras of Taormina, about AD 40

- James the Just, in AD 62, after being condemned by the Sanhedrin

- Possibly Saint Timothy (by Hellenistic pagans), after AD 67

- Constantine-Silvanus, founder of the Paulicians, stoned in 684 in Armenia

- Chase (son of Ioube), Muslim Byzantine official of Arab origin, stoned in 915 at Athens

- Saint Eskil, Anglo-Saxon monk stoned to death by Swedish Vikings, about 1080

- Moctezuma II, 1520, last Aztec Emperor (according to Western accounts; whereas, according to Aztec accounts, the Spanish killed him)

Averted

- Xenophon mentions in his Anabasis, 4th century BCE, that several people are accused and suggested stoned, but averted, including Xenophon himself

Modern

- Soraya Manutchehri, 1986, a 35-year-old woman stoned to death in Iran after unconfirmed accusations of adultery

- Du'a Khalil Aswad, 2007, a 17-year-old girl stoned to death in Iraq

Averted

- Amina Lawal was sentenced to death by stoning in Nigeria in 2002 but freed on appeal.

- Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani was sentenced to death by stoning in Iran in 2006. Following a review the sentence was commuted and she was released in 2014.[121]

See also

Related methods of execution

- Ishikozume (Japan)

- Crushing

- Cement shoes

Individuals

References

- ^ a b c d e Emma Batha (September 29, 2013). "Stoning – where does it happen?". www.trust.org/. Thomson Reuters Foundation. Archived from the original on 2015-11-17. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ a b c Batha, Emma (29 September 2013). "Special report: The punishment was death by stoning. The crime? Having a mobile phone". The Independent. London: independent.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2013-10-06. Retrieved October 4, 2013.

- ^ Ida Lichter, Muslim Women Reformers: Inspiring Voices Against Oppression, ISBN 978-1591027164, p. 189

- ^ Tamkin, Emily (March 28, 2019). "Brunei makes gay sex and adultery punishable by death by stoning". Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 30, 2019. Retrieved April 1, 2019.

- ^ Frolov, Dmitry V. (2006). "Stoning". In Jane Dammen McAuliffe (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. Brill. doi:10.1163/1875-3922_q3_EQSIM_00404.

- ^ a b Haim Hermann Cohn (2008). "Capital Punishment. In the Bible & Talmudic Law". Encyclopaedia Judaica. The Gale Group. Archived from the original on 2021-04-17. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ^ a b W. R. F. Browning, ed. (2010). "Stoning". A Dictionary of the Bible (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954398-4. Archived from the original on 2019-04-07. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ^ Glen Warren Bowersock; Peter Brown; Oleg Grabar (1999). Late Antiquity: A Guide to the Postclassical World. Harvard University Press. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-674-51173-6.

- ^ Semerdjian, Elyse (2009). "Zinah". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530513-5. Archived from the original on 2017-02-25. Retrieved 2017-06-24.

- ^ a b c d e Vikør, Knut S. (2014). "Sharīʿah". In Emad El-Din Shahin (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Islam and Politics. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on June 4, 2014.

- ^ a b c Otto, Jan Michiel (2008). Sharia and National Law in Muslim Countries: Tensions and Opportunities for Dutch and EU Foreign Policy (PDF). Amsterdam University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-90-8728-048-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-09. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ^ a b Mayer, Ann Elizabeth (2009). "Law. Modern Legal Reform". In John L. Esposito (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of the Islamic World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008.

- ^ a b Stewart, Devin J. (2013). "Shari'a". In Gerhard Böwering, Patricia Crone (ed.). The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought. Princeton University Press. pp. 503–504.

- ^ Lapidus, Ira M. (2014). A History of Islamic Societies. Cambridge University Press (Kindle edition). p. 835. ISBN 978-0-521-51430-9.

- ^ Otto, Jan Michiel (2008). Sharia and National Law in Muslim Countries: Tensions and Opportunities for Dutch and EU Foreign Policy (PDF). Amsterdam University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-90-8728-048-2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-10-09. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ^ Tellenbach, Silvia (2015). "Islamic Criminal Law". In Markus D. Dubber; Tatjana Hornle (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Criminal Law. Oxford University Press. pp. 249–250.

- ^ Vikør, Knut S. (2005). Between God and the Sultan: A History of Islamic Law. Oxford University Press. pp. 266–267.

- ^ "How political hatred during Cultural Revolution led to murder and cannibalism in a small town in China". South China Morning Post. 2016-05-11. Archived from the original on 2019-12-04. Retrieved 2019-11-30.

- ^ "Capital Punishment". JewishEncyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 2024-05-31. Retrieved 2010-09-12.

- ^ Dmitry V. Frolov (2006). "Stoning". In Jane Dammen McAuliffe (ed.). Encyclopaedia of the Qurʾān. Vol. 5. Brill. p. 130.

- ^ Handley, Paul (11 Sep 2010). "Islamic countries under pressure over stoning". Times of Malta. Archived from the original on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ Sommerville, Quentin (26 Jan 2011). "Afghan police pledge justice for Taliban stoning". BBC. Archived from the original on 2011-04-06. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^ Nebehay, Stephanie (10 Jul 2009). "Pillay accuses Somali rebels of possible war crimes". The Times of India. Archived from the original on 2015-01-20. Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ^

Sandhu, Serina (4 November 2015). "Afghan woman accused of adultery stoned to death in video posted online". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2015-12-07. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

According to Tolo News Agency, Police Chief General Mustafa said: "The Taliban ordered stoning of the girl after she was caught eloping with a man on the mountains. Police has started investigations and will arrest the perpetrators soon." But Wazhma Frogh, co-founder of the Research Institute for Women, Peace and Security, said the attackers could have been tribal leaders as local officials were known to blame Taliban insurgents "to cover up their own kind". She told The Guardian: "Of course the Taliban do these things, but we can't deny that tribal leaders also do the same things."

- ^ a b Rasmussen, Sune Engel (3 November 2015). "Afghan woman stoned to death for alleged adultery". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2016-12-17.

- ^ Hassan Hakimi, ed. (November 8, 2015). "Stoning Rukhshana was against Shariah: Ghor Ulema". Pajhwok Afghan News. Archived from the original on 2016-01-25. Retrieved November 8, 2015.

- ^ King, Laura (22 August 2010). "Young lovers killed by stoning in Afghanistan". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 2015-12-08. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ "Afghanistan: Reject Proposal to Restore Stoning". www.hrw.org. Human Rights Watch. 25 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2015-11-23. Retrieved 27 November 2015.

- ^ McKay, Hollie (2021-09-13). "Taliban bring back 'virtue' ministry, stoning and amputations for 'major sins'". New York Post. Archived from the original on 2022-11-12. Retrieved 2022-11-12.

- ^ "BBC article dated September 22, 2021". Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ "Forbes website, article by Dr Ewelina U Ochab, dated May 14, 2023". Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ "United Nations press release dated May 11, 2023". Archived from the original on August 27, 2023. Retrieved August 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Westcott, Ben (28 March 2019). "Brunei to punish gay sex and adultery with death by stoning". CNN. Archived from the original on 3 July 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ "Iran 'adulterer' stoned to death". BBC News. 10 July 2007. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 3 December 2012.

- ^ "Iran to scrap death by stoning". AFP. August 6, 2008. Archived from the original on June 6, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ^ Iran executes two men by stoning Archived 2014-09-03 at the Wayback Machine BBC News (January 13, 2009)

- ^ a b "Iran". Cornell Center on the Death Penalty Worldwide. 2014. Archived from the original on July 27, 2019. Retrieved Apr 7, 2019.

- ^ a b Mohammad Hossein Nayyeri, The Question of "Stoning to Death" in the New Penal Code of the IRI Archived 2014-11-04 at the Wayback Machine Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (2014)

- ^ «سنگسار» در شرع حذف شدنی نیست Archived 2014-03-14 at the Wayback Machine Persian document; Translation – "Muhammad Ali Asfnany spokesman for the Judicial Committee of the Parliament said Rajm is not being listed in the legislation, but the punishment per the law will be practically the same as the rest of the rules are valid in Islamic law. Asfnany said Western media makes noise against the implementation of Islamic law in Iran, a sentiment that is rooted in Western enmity with us, when their excuse is to change our rules."

- ^ a b c d Amnesty International (2008), Iran – End executions by Stoning Archived 2015-11-08 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Richard Johnson (20 November 2010). "Anatomy of a stoning – How the law is applied in Iran". National Post. Archived from the original on 2013-01-04. Retrieved 2010-11-21.

- ^ English Translation of Regulatory Code on Sentences of Qisas, Stoning, Crucifixion, Execution, and Flogging Archived 2014-11-03 at the Wayback Machine Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (2013)

- ^ a b Iran Human Rights Documentation Center (April 2014), English Translation of Books I & II of the New Islamic Penal Code Archived 2014-11-03 at the Wayback Machine IHRDC, New Haven, CT

- ^ National Laws – Iran Archived 2014-11-03 at the Wayback Machine (2014)

- ^ Katie Hamann Aceh's Sharia Law Still Controversial in Indonesia Archived 2010-10-03 at the Wayback Machine Voice of America 29 December 2009, and: In Enforcing Shariah Law, Religious Police in Aceh on Hemline Frontline Archived 2016-03-05 at the Wayback Machine Jakarta Globe, December 28, 2009

- ^ Aceh Stoning Law Hits a New Wall Archived 2016-01-25 at the Wayback Machine The Jakarta Globe, 12th October 2009

- ^ Aceh Government Removes Stoning Sentence From Draft Bylaw Archived 2016-01-25 at the Wayback Machine, Jakarta Globe 12 March 2013

- ^ "Iraq: Amnesty International appalled by stoning to death of Yazidi girl and subsequent killings" (PDF). Amnesty International. 27 April 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-04-21. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ Ahmed Rasheed; Mohammed Ameer (10 March 2012). "Iraq militia stone youths to death for "emo" style". Archived from the original on 2014-09-17. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ^ Islamic State militants stone man to death in Iraq: witness Archived 2015-10-01 at the Wayback Machine Reuters (August 22, 2014)

- ^ Gunnar J. Weimann (2010). Islamic Criminal Law in Northern Nigeria: Politics, Religion, Judicial Practice. Amsterdam University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-90-5629-655-1. Archived from the original on 2024-05-31. Retrieved 2019-04-07.

- ^ John L. Esposito; Dalia Mogahed (2008). Who Speaks For Islam?: What a Billion Muslims Really Think. Gallup Press (Kindle edition). p. Kindle loc. 370.

- ^ "Gay Nigerians face Sharia death". BBC News. 10 Aug 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-04-08. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ Coleman, Sarah (Dec 2003). "Nigeria: Stoning Suspended". World Press. Archived from the original on 2011-12-03. Retrieved 8 June 2011.

- ^ Lau, Martin (1 September 2007). "Twenty-Five Years of Hudood Ordinances – A Review". Washington and Lee Law Review. 64 (4): 1292, 1296. Archived from the original on 2014-11-29. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- ^ "Slow March to the Gallows: Death Penalty in Pakistan" (PDF). /www.fidh.org. Intl. Fed. for Human Rights. 2007. pp. 16, 58. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-19. Retrieved 2015-11-18.

- ^ "Overview of the Protection of Women Act, 2006 (Pakistan)" (PDF). af.org.pk. Islamabad: Aurat Publication and Information Service Foundation. 2008. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-11-19. Retrieved 18 November 2015.

- ^ "Pak soldier publicly stoned to death for love affair". Reuters. 2013-03-13. Archived from the original on 2015-11-19. Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- ^ "Woman Stoned to Death on Panchayat's Orders". Pakistan Today. Lahore. 10 July 2013. Archived from the original on 2013-08-20. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ^ "Pakistani couple stoned to death for adultery; six arrested". Reuters. 17 February 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-11-21. Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- ^ "Pregnant Pakistani woman stoned to death by her family". The Guardian. London: theguardian.com. 28 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-05-27. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ "Pakistani man protesting 'honour killing' admits strangling first wife". The Guardian. London: theguardian.com. 29 May 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-05-29. Retrieved May 27, 2014.

- ^ "Abolish Stoning and Barbaric Punishment Worldwide!". International Society for Human Rights. Archived from the original on 2010-10-12. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ^ Batha, Emma; Li, Ye (29 September 2013). "Stoning – where is it legal?". Thomson Reuters Foundation. Archived from the original on 2014-01-27. Retrieved January 26, 2014.

- ^ Vogel, Frank E. (1999). Islamic law and legal system: studies of Saudi Arabia. p. 246. ISBN 978-90-04-11062-5.

- ^ a b "Sudan –End stoning, reform the criminal law". Sudan Tribune. 30 July 2012. Archived from the original on 4 August 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ "Sudan: Amnesty International e Italians for Darfur mobilitati contro lapidazione di Layla" (in Italian). LiberoReporter. Archived from the original on 6 August 2012. Retrieved 18 August 2012.

- ^ "Sudan Sentences a Woman to be Stoned to Death Based on Islamic Law". 28 July 2022. Archived from the original on 31 May 2024. Retrieved 29 July 2022.

- ^ "Somalia: Girl stoned was a child of 13". Amnesty International. 2008-10-31. Archived from the original on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "Somali woman executed by stoning". BBC News. 2008-10-27. Archived from the original on 2008-10-30. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ^ "Stoning victim 'begged for mercy'". BBC News. 2008-11-04. Archived from the original on 2015-07-24. Retrieved 2010-05-24.

- ^ "Somali militants stone woman to death". Reuters. 27 September 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-10-01. Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- ^ "Federal Decree Law No. (15) of 2020". Ministry of Justice. 27 September 2020. Pages 1, Article 1 "The provisions of the Islamic Shari’a shall apply to the retribution and blood money crimes. Other crimes and their respective punishments shall be provided for in accordance with the provisions of this Law and other applicable penal codes". Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ "Article 354 of Federal Law 3 of the Penal Code (Prohibition of Sexual Violence)". evaw-global-database.unwomen.org. Archived from the original on 2021-01-21. Retrieved 2020-11-24.

- ^ "LGBT Couple Safety Worldwide". forktip.com. 2020-09-16. Archived from the original on 2021-05-26.

- ^ Douglas, Benji (14 September 2012). "Gays In The United Arab Emirates Face Flogging, Hormone Injections, Prison". www.queerty.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "» A Guide To Moving To The UAE – Laws & Regulations". 8 August 2012. Archived from the original on 6 August 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ "Homosexuality in the UAE". detainedindubai. Archived from the original on 2017-12-22. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ^ Nordland, Rod (11 November 2017). "Holding Hands, Drinking Wine and Other Ways to Go to Jail in Dubai". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ "Homosexuality can still mean the death penalty in many countries". thejournal.ie. 9 September 2018. Archived from the original on 3 August 2019. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- ^ Duffy, Nick (22 December 2015). "Judge blocks extradition of gay British man to UAE, where gays can face death penalty". PinkNews. Archived from the original on 22 May 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Dawn Ennis (October 5, 2016). "One photo of gay man in drag lands him on death row in Abu Dhabi". LGBT Nation. Archived from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved December 12, 2021.

- ^ Youssef, Marten (21 February 2010). "Call for more information on the death penalty". The National. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ Wheeler, Julie (28 February 2000). "UAE death sentence by stoning". BBC News. Archived from the original on 5 February 2022. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ Jahanhir, Asma (17 January 2001). "Droits Civils et Politiques et Notamment Dispartitions et Exécutions Sommaires" (PDF). Conseil Économique et Social des Nations Unies (in French). Archived (PDF) from the original on 31 May 2024. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ Amnesty International (12 June 2006). "UAE: Death by stoning / flogging". Archived from the original on 26 August 2019. Retrieved 4 February 2022.

- ^ Al Deberkey, Salah (11 June 2006). "Fujairah Shariah court orders man to be stoned to death for adultery". Khaleej Times. Archived from the original on 8 July 2006.

- ^ "Man, woman stoned to death for adultery in Syria: monitor". Reuters. 21 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- ^ "Islamic State militants stone man to death in Iraq: witness". Reuters. 22 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-10-01. Retrieved 2017-07-02.

- ^ a b "Islamic State video 'shows man stone his daughter to death'". BBC News. 21 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2017-02-15. Retrieved 2018-06-20.

- ^ Memri TV: "#4558 Woman Stoned to Death by ISIS in Syria" Archived 2015-11-08 at the Wayback Machine October 21, 2014

- ^ Marisela Ortega (29 September 2010). "Man, sons convicted of stoning El Paso woman to death in Juárez". El Paso Times. Retrieved 2010-10-13.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Accused thief stoned to death in Mexico". Lewiston Sun Journal. 2009-02-22. Archived from the original on 2023-09-04. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Small-town mayor stoned to death in western Mexico". San Diego Union-Tribune. 2010-09-27. Archived from the original on 2023-09-04. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2023-09-04. Retrieved 2023-09-04.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "2 Migrants Stoned to Death by Smugglers at Southern Border in Tijuana". The Daily Signal. 2023-02-21. Archived from the original on 2023-09-04. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Mexican Women Stoned to Death". The New York Times. 1934-11-13. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2023-09-04. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Ugly lynchings in Guatemala a legacy of war". The Globe and Mail. 2000-08-04. Archived from the original on 2022-12-08. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Mob stones brothers to death in Guatemala". www.latinamericanstudies.org. Archived from the original on 2023-09-04. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "BBC News | AMERICAS | Two stoned to death in Guatemala". news.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2023-11-20. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Mob stones brothers to death in Guatemala". www.latinamericanstudies.org. Archived from the original on 2023-09-04. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ "Honduran police arrest five after mob of 600 lynches Italian man". Reuters. 2021-07-10. Archived from the original on 2023-09-04. Retrieved 2023-09-15.

- ^ Durand, Greg Loren. "The Object and Cause of True Santification". Judicial Warfare: Christian Reconstruction and Its Blueprints for Dominion. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013.

- ^ Invitation to a Stoning Archived 2014-04-02 at the Wayback Machine, Reason.com, Walter Olson, November 1998. Retrieved May 1, 2014.

- ^ Clarkson, Frederick (1995). "Christian Reconstruction: Theocratic Dominionism Gains Influence". Eyes Right!: Challenging the Right Wing Backlash. South End Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-0-89608-523-7. Archived from the original on 2024-05-31. Retrieved 2018-01-05.

- ^ Vile, John R. (2003). "Christian Reconstruction". Encyclopedia of Constitutional Amendments, Proposed Amendments, and Amending Issues, 1789–2002 (2nd ed.). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-85109-428-8. OCLC 51553072. Archived from the original on 2024-05-31. Retrieved 2018-01-05.

...North favors stoning,...because of the widespread availability of rocks....

Retrieved 1 May 2014. - ^ a b c d e f g "Muslim Beliefs About Sharia". Pew Research Center's Religion & Public Life Project. 30 April 2013. Archived from the original on 2014-08-30. Retrieved 2015-02-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The World's Muslims: Religion, Politics and Society" (PDF). Pew Forum. Pew Research Center's Forum on Religion & Public Life. 2013. p. 221. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-30. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ^ "Amina Lawal". Amnesty International. 2003. Archived from the original on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ "Nigeria: Debunking Misconceptions on Stoning Case". Human Rights Watch. 2003. Archived from the original on 2016-01-25. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ Rochelle Terman (November 2007). "The Stop Stoning Forever Campaign: A Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-11-28. Retrieved 2010-09-23.

- ^ a b "Afghanistan: Reject stoning, flogging, amputation and other Taliban-era punishments". amnesty.org – Amnesty International. 26 November 2013. Archived from the original on 2015-11-19. Retrieved 2015-11-04.

- ^ "Sudan: Ban Death by Stoning". hrw.org – Human Rights Watch. 31 May 2012. Archived from the original on 2017-01-15. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- ^ "Iran Human Rights Documentation Center – Gender Inequality and Discrimination: The Case of Iranian Women". iranhrdc.org. Archived from the original on 2014-03-02. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ^

"Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-03-13. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "2012 International Women's Day « Institut international des droits de l'homme et de la Paix (2IDHP)". 2idhp.eu. Archived from the original on 2014-03-13. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ^ "Activists push for global ban on stoning". wluml.org. Archived from the original on 2014-03-13. Retrieved 2014-03-13.

- ^ "Amnesty International – Iran: Death by stoning, a grotesque and unacceptable penalty". amnesty.org. 15 January 2008. Archived from the original on 20 October 2013.

- ^ "Gay Nigerians face Sharia death". BBC News. 10 August 2007. Archived from the original on 2011-04-08. Retrieved 2011-06-08.

- ^ "Here are the 10 countries where homosexuality may be punished by death - The Washington Post". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2022-01-04. Retrieved 2021-12-12.

- ^ Tomlinson, Hugh (19 March 2014). "Ashtiani freed after 9 years on death row". The Times. Archived from the original on 2015-04-16. Retrieved 10 April 2015.

External links

- Frequently Asked Questions About Stoning

- Stoning and Human Rights Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Stoning and Islam Archived 2013-09-27 at the Wayback Machine

- Extract of the Kitab Al-Hudud (The book pertaining to punishments prescribed by Islam)

- Khaleej Times Archived 2012-05-09 at the Wayback Machine (United Arab Emirates: Fujairah Shariah court orders man to be stoned to death for adultery – 11 June 2006)

- Muslims against stoning

- QuranicPath – Qur'an against stoning

- 1991 Video of Stoning of Death in Iran: WMV format | RealPlayer

- Graphic: Anatomy of a stoning (National Post, November 20, 2010)

- Amnesty International 2008, "Campaigning to end stoning in Iran" Archived 2014-11-27 at the Wayback Machine