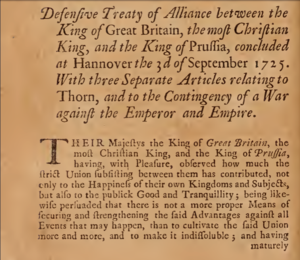

The Treaty of Hanover was a treaty of defensive alliance signed on 3 September 1725 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, the Electorate of Hanover, the Kingdom of France and the Kingdom of Prussia. The alliance was formed to combat the power of the Austro-Spanish alliance, which was founded at the Peace of Vienna months earlier in May 1725.[1]

| Defensive Treaty of Alliance between the King of Great Britain, the most Christian King, and the King of Prussia, concluded at Hannover the 3rd of September 1725. | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Defensive Alliance |

| Context | Stately Quadrille |

| Signed | 3 September 1725 |

| Location | Hannover, Germany |

| Effective | 30 September 1725 |

| Signatories | List

|

| Ratifiers | |

| Language | French |

The United Provinces and the Kingdom of Sweden later acceded to the Hanoverian Alliance through the Treaties of The Hague (1726) and Stockholm (1727).[1] The Kingdom of Denmark-Norway did not formally join the Hanoverian Alliance but signed the Treaty of Copenhagen with Great Britain and France in April 1727.[2] In 1728, Prussia would ally itself with Emperor Charles VI and the Viennese Alliance by signing the secret Treaty of Berlin.

Principal conditions edit

Alliance provisions edit

Reasoning and formation of Hanoverian Alliance edit

The Spanish, who were allies and close friends of the Habsburg monarchy following the succession of Charles I (V) to the Spanish throne in 1516, broke their partnership with the Austrians in 1700. This was due to the death of Charles II, the last Habsburg king of Spain, who died without issue.[3] King Charles II appointed Philip de Bourbon, Duke of Anjou as his successor.[4] The following succession crisis sparked the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714), and consequently ended the two century alliance between Austria and Spain.

After the defeat of the Spanish in the War of the Quadruple Alliance (1717-1720), the Austrians decided to ally the Spanish once again in order to reset the balance of power in Europe; which had leaned towards France in recent years. King George I had also become wary of a renewed hegemony of Europe by Spain and the Empire. The Treaty of Hanover marks the beginning of the Hanoverian Alliance as a formal opposition to the renewed Austro-Spanish alliance (which would later be joined by the Russian Empire, and the Electorates of Bavaria and Cologne in 1726).[5][6] Separate reassurances of full military support were also given in the event of the Holy Roman Empire attacking the French unexpectedly.[1]

"There shall be now, and in all Time coming, a true, firm, and inviolable Peace, the most sincere and intimate Friendship, and the most strict Alliance and Union between the said three most serene Kings, their Heirs and Successors...and prevent and repel all Wrongs and Damages, by the most proper means they can find out."

edit

It was agreed among the signers that approximate amounts of troops and cavalry would be supplied immediately in support if an enemy were to declare war. Great Britain and France would both send eight thousand troops and four thousand cavalry, while Prussia would send only three thousand troops and two thousand cavalry.[1] Naval support was also guaranteed if needed.[1]

Separate Article edit

City of Thorn edit

In 1714, a religious massacre occurred in Polish-ruled Royal Prussia called the Tumult of Thorn. Religious tensions had been present in the city since the Jesuits entered into Thorn due to Poland-Lithuania's acceptance of the Counter-Reformation in 1595. After the Treaty of Oliva[a] in 1660, religious tolerance was enforced in Royal Prussia; the city had become about half Catholic and half Lutheran.[7]

On 16 and 17 March 1726, the Jesuits were celebrating the feast day of Corpus Christi[b] when Jesuit student of a monastery complained that Lutherans who were watching the procession did not take off their hats or kneel before the statue of Mary. Fights on both sides ensued, and a Jesuit monastery was damaged.[8]

Jesuits were badly beaten, portraits of Catholic saints were destroyed, and part of the altar was damaged. The Lutherans also gathered a pile of Catholic books and paintings, which were set on fire outside the monastery.[8] After these events, the Jesuits sued the City in the Polish Supreme Court in Warsaw. The court, directed by King Augustus II,[c] issued a verdict where thirteen Lutherans were set to be executed.[9]

Great Britain and Prussia, who both guaranteed the Treaty of Oliva, were greatly concerned with this massacre.[1] The Polish court's verdict revealed religious intolerance present in Poland towards its Lutheran population, which both powers believed needed to be corrected and damaged Poland's international reputation.[10] Prussia and Great Britain agreed to concert efforts towards Poland to enforce tolerance in the area.[1]

Footnotes edit

- ^ Treaty of peace which ended the Second Northern War 1555-1560.

- ^ A Catholic religious ceremony celebrating the transubstantiation of the Eucharist during the Mass.

- ^ Originally Elector of Saxony who was elected King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania in 1697, reinstated in 1706

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g Knapton, J.J. & P. (1732). A General Collection of Treaties of Peace and Commerce, Manifestos, Declarations of War, and other Publick Papers, from the End of the Reign of Queen Anne to the Year 1731. Volume IV. University of Toronto. pp 158-186

- ^ Treaties, Oxford Historical (16 April 1727). "Treaty of Alliance between Denmark, France, and Great Britain, signed at Copenhagen, 16 April 1727". Oxford Public International Law.

- ^ Henry., Kamen (2001). Philip V of Spain : the king who reigned twice. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300087185. OCLC 45499749.

- ^ Onnekink, David (29 March 2017). Redefining William III : the impact of the king stadholder in international context. London. ISBN 978-1138257962. OCLC 993014462.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Treaties, Oxford Historical (3 November 1726). "Treaty of Alliance between the Emperor and Russia, signed at Vienna, 6 August 1726". Oxford Public International Law. doi:10.1093/law:oht/law-oht-32-CTS-285.regGroup.1/law-oht-32-CTS-285 (inactive 31 January 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - ^ Treaties, Oxford Historical (24 October 1726). "Treaty of Alliance and Subsidy between Bavaria, Cologne and the Emperor, signed at Vienna, 1 September 1726". Oxford Public International Law. doi:10.1093/law:oht/law-oht-32-CTS-331.regGroup.1/law-oht-32-CTS-331 (inactive 31 January 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 (link) - ^ Davies, Norman (2001). Heart of Europe : the past in Poland's present (New ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-1423769422. OCLC 67983594.

- ^ a b Morton, Michael; Koepke, Wulf (February 1988). "Johann Gottfried Herder". German Studies Review. 11 (1): 145. doi:10.2307/1430850. ISSN 0149-7952. JSTOR 1430850.

- ^ Wandycz, Piotr S.; Davies, Norman (April 1983). "God's Playground: A History of Poland". The American Historical Review. 88 (2): 436. doi:10.2307/1865504. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 1865504.

- ^ Friedrich, Karin (2000). The Other Prussia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511470646. ISBN 9780511470646.