The Train is a 1964 war film directed by John Frankenheimer[1] and starring Burt Lancaster, Paul Scofield and Jeanne Moreau. The picture's screenplay—written by Franklin Coen, Frank Davis, and Walter Bernstein—is loosely based on the non-fiction book Le front de l'art by Rose Valland, who documented the works of art placed in storage that had been looted by Nazi Germany from museums and private art collections. Arthur Penn was The Train's original director, but was replaced by Frankenheimer three days after filming had begun.

| The Train | |

|---|---|

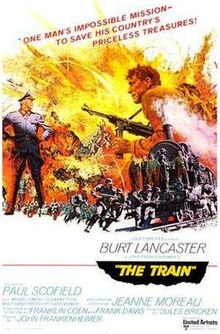

Theatrical release poster by Frank McCarthy | |

| Directed by | John Frankenheimer |

| Written by | Franklin Coen Frank Davis Walter Bernstein |

| Produced by | Jules Bricken |

| Starring | Burt Lancaster Paul Scofield Jeanne Moreau Michel Simon |

| Cinematography | Jean Tournier Walter Wottitz |

| Edited by | David Bretherton |

| Music by | Maurice Jarre |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release dates | September 24, 1964 (France) October 29, 1964 (United Kingdom) March 7, 1965 (United States) |

Running time | 133 minutes[1] |

| Countries | United States[1] France |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $5.8 million[2] |

| Box office | $6.8 million[2] |

Set in August 1944 during World War II, it pits French Resistance-member Paul Labiche (Lancaster) against German Colonel Franz von Waldheim (Scofield), who is attempting to move stolen art masterpieces by train to Germany. Inspiration for the scenes of the train's interception came from the real-life events surrounding train No. 40,044 as it was seized and examined by Lt. Alexandre Rosenberg of the Free French forces outside Paris.

Plot edit

In August 1944, masterpieces of modern art stolen by the Wehrmacht are being shipped to Germany; the officer in charge of the operation, Colonel Franz von Waldheim, is determined to take the paintings to Germany, no matter what the cost. After the works he selects are removed from the Jeu de Paume Museum, curator Mademoiselle Villard seeks help from the French Resistance. Given the imminent liberation of Paris by the Allies, SNCF (French National Railways) workers associated with the Resistance need only delay the train for a few days, but it is a dangerous operation and must be done without risking the priceless cargo.

Resistance cell leader and SNCF area inspector Paul Labiche initially denies the plan, telling Mlle. Villard and senior Resistance leader Spinet, "I won't waste lives on paintings." He has a change of heart after his cantankerous former mentor, Papa Boule, is summarily executed for sabotaging the train on his own. After that sacrifice, Labiche joins his Resistance teammates Didont and Pesquet, who have been organizing their own plan with the help of other SNCF Resistance members. In an elaborate ruse, they reroute the train, temporarily changing railway station signage to make the German escort believe they are heading to Germany when they have actually looped back round towards Paris. Two deliberate collisions then block the train in at the small town of Rive-Reine without damaging the cargo. Labiche, although shot in the leg, escapes on foot with the help of Christine, the widowed owner of a Rive-Reine hotel, while other Resistance members involved in the plot are murdered, including Pesquet and Jacques, the Rive-Reine stationmaster.

That night, Labiche and Didont meet Spinet again, along with Jacques's young nephew Robert, and plan to paint the tops of three wagons white to warn off Allied aircraft from bombing the art train. Robert recruits railroad workers and friends of his uncle. He and Didont are killed when the painting is detected during a false air raid alarm staged by Robert, but because of the paint, the train is spared from bombing the next day when Allied medium bombers roar over Rive-Reine.

Now working alone, Labiche continues to delay the train after the tracks are cleared, to the mounting rage of von Waldheim. Labiche attempts to use plastic explosives to destroy the locomotive, only to find it carrying French hostages placed by the Germans. To spare the hostages, he blows the explosives early, damaging the tracks in front of the train. While the Germans fix the tracks, Labiche runs ahead, struggling to keep away from the soldiers searching for him. Finally, he manages to derail the train by unscrewing and loosening one of the rails, causing the rails to spread and the engine to fall gently into the ballast without harming the hostages.

No crane is available to re-rail the train, so Von Waldheim flags down an army convoy retreating on a nearby road, learning that a French armored division is not far behind. The colonel orders the train to be unloaded and attempts to commandeer the trucks for the art, but the convoy's commander refuses the order. The train's German contingent then kill the hostages and join the retreating convoy.

Von Waldheim remains behind with the abandoned train. Strewn between the track and the road are crates labeled with the names of famous artists. Labiche appears and the colonel castigates him for having no real interest in the art he has saved. In response, Labiche turns and looks at the murdered hostages and then, without a word, turns back to von Waldheim and shoots him dead. Afterwards Labiche limps away, leaving the bodies and the art treasures where they lie.

Cast edit

Sourced to the American Film Institute.[1]

- Burt Lancaster as Paul Labiche

- Paul Scofield as Colonel Franz von Waldheim

- Jeanne Moreau as Christine

- Suzanne Flon as Mlle Villard

- Michel Simon as Papa Boule

- Wolfgang Preiss as Major Herren

- Albert Rémy as Didont

- Charles Millot as Pesquet

- Jean Bouchaud as Hauptmann Schmidt

- Richard Münch as General von Lubitz

- Jacques Marin as Jacques

- Paul Bonifas as Spinet

- Donald O'Brien as Sergeant Schwartz

- Arthur Brauss as Lieutenant Pilzer

- Bernard La Jarrige as Bernard

- Daniel Lecourtois as Priest

- Gérard Buhr as Corporal

- Howard Vernon as Hauptmann Dietrich

- Nick Dimitri as German soldier

- Christian Fuin as Robert

- Christian Rémy as Tauber

- Helmo Kindermann as Ordnance officer

- Jacques Blot as Hubert

- Jean-Claude Berco as Major

- Jean-Jacques Lecomte as Lieutenant of retreating convoy

- Jean-Pierre Zola as Octave

- Louis Falavigna as Railroad worker

- Max From as Gestapo officer

- Richard Bailey as Grote

- Roger Lumont as Engineer officer

Historical background edit

The Train is based on the factual 1961 book Le front de l'art by Rose Valland, the art historian at the Jeu de Paume, who documented the works of art placed in storage there that had been looted by the Germans from museums and private art collections throughout France and were being sorted for shipment to Germany in World War II.

In contrast to the action and drama depicted in the film, the shipment of art that the Germans were attempting to take out of Paris on August 1, 1944, was held up by the French Resistance with an endless barrage of paperwork and red tape and made it no farther than a railyard a few miles outside Paris.[3]

The train's actual interception was inspired by the real-life events surrounding train No. 40,044 as it was seized and examined by Lt. Alexandre Rosenberg of the Free French forces outside Paris in August 1944. Upon his soldiers' opening the wagon doors, he viewed many plundered pieces of art that had once been displayed in the home of his father, the Parisian art dealer Paul Rosenberg, one of the world's major Modern art dealers.[4]

Artworks seen in the film's opening scenes prominently include paintings that in reality were not looted by the Germans such as When Will You Marry? by Paul Gauguin and Girl with a Mandolin by Pablo Picasso.

Production edit

Frankenheimer inherited the film from another director, Arthur Penn. Lancaster fired Penn after three days of filming in France,[5] and asked Frankenheimer to assume the role of director. Penn envisioned a more intimate film that would muse on the role art played in Lancaster's character, and why he would risk his life to save the country's great art from the Nazis. He did not intend to give much focus to the mechanics of the train operation itself. But Lancaster wanted more emphasis on action to ensure that the film would be a hit, after the failure of his film The Leopard.[citation needed] The production was shut down briefly while the script was rewritten, and the budget doubled. As he recounts in the Champlin book, Frankenheimer used the production's desperation to his advantage in negotiations. He demanded and was given the following: his name was made part of the title, "John Frankenheimer's The Train"; the French co-director, demanded by French tax laws, was not allowed to ever set foot on set; he was given total final cut; and a Ferrari.[6] Much of the film was shot on location.

The Train contains multiple real train wrecks. The Allied bombing of a rail yard was accomplished with real dynamite, as the French rail authority needed to enlarge the track gauge. This can be observed by the shockwaves travelling through the ground during the action sequence. Producers realized after filming that the story needed another action scene and reassembled some of the cast for a Spitfire attack scene that was inserted into the first third of the film. French Armée de l'Air Douglas A-26 Invaders are also seen later in the film.[7]

The film includes a number of sequences involving long tracking shots and wide-angle lenses, with deep focus photography. Noteworthy tracking shots include Labiche attempting to flag down a train and jumping onto the moving locomotive, a long dolly shot of von Waldheim travelling through a marshalling yard at high speed in a motorcycle sidecar, and Labiche rolling down a mountain and across a road, finally staggering down to a railroad track.

Frankenheimer remarked on the DVD commentary, "Incidentally, I think this was the last big action picture ever made in black and white, and I am personally so grateful that it was filmed in black and white. I think the black and white adds tremendously to the movie." Throughout the film, Frankenheimer often juxtaposed the value of art with the value of human life. A brief montage ends the film, intercutting the crates full of paintings with the dead bodies of the French hostages, before a final shot shows Labiche walking away down the road.[8]

Locations edit

Filming took place in several locations, including: Acquigny (Calvados; Saint-Ouen, Seine-Saint-Denis; and Vaires, Seine-et-Marne. The shots span from Paris to Metz. Much of the film is centred in the fictional town called "Rive-Reine".

'Circular journey'

Actual train route: Paris, Vaires, Rive-Reine, Montmirail, Châlons-sur-Marne, St Menehould, Verdun, Metz, Pont-à-Mousson, Sorcy (Level Crossing), Commercy, Vitry Le Francois, Rive-Reine.

Planned route from Metz to Germany: Remilly, Teting (level crossing), Saint Avold, Zweibrücken.

Locomotives used edit

The chief locomotives used were examples of the former Chemins de fer de l'Est Series 11s 4-6-0, which the SNCF classified as 1-230-B.[citation needed] 1-230.B.517 was specified as Papa Boule's locomotive and features particularly prominently, flanked by sister locomotives 1-230.B.739 and 1-230.B.855. A decommissioned locomotive doubled as the 517 for the crash scene (a production still of the aftermath from the rear shows the tender identification number reading 1-230.B.754), and another was given a plywood armoured casing to depict a German Army locomotive for the yard manoeuvres-and-raid scene. An ancient "Bourbonnais" type 030.C 0-6-0 (N° 757), apparently decommissioned by SNCF, was deliberately wrecked to block the line; it moved faster than the film crew anticipated and smashed three of the five cameras placed near to the track in the process.[9] Other engines of various classes can be seen on background sidings in the run-by scenes and in aerial views of the yard, among them SNCF Class 141R 2-8-2 engines, which were not supplied to France until after the war as part of the railway's reconstruction, as well as USATC S100 Class 0-6-0T tank engines, designated by the SNCF as 030TU, which were used by the approaching Allied forces.

Reception edit

After a production cost of $6.7 million,[10] The Train earned $3 million in the US and $6 million elsewhere.[11] The film was one of the 13 most popular films in the UK in 1965.[12]

Awards and nominations edit

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Story and Screenplay – Written Directly for the Screen | Franklin Coen and Frank Davis | Nominated | [13] |

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Film from any Source | John Frankenheimer | Nominated | [14] |

| Laurel Awards | Best Action Performance | Burt Lancaster | Nominated | |

| National Board of Review Awards | Top Ten Films | 9th Place | [15] | |

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d e "The Train". American Film Institute. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ a b "The Train, Box Office Information." The Numbers. Retrieved: January 22, 2013.

- ^ "DVD enclosure booklet: The Train". MGM Home Entertainment.

- ^ Cohen, Patricia and Tom Mashberg. "Family, 'Not Willing to Forget,' Pursues Art It Lost to Nazis". The New York Times, April 27, 2013, p. A1; published online April 26, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2013.

- ^ p. 15, p.47 Penn, Arthur Arthur Penn: Interviews Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2008

- ^ Mackieon, Drew. "Nine Reasons to Watch The Train", KCET presents, December 18, 2011. Retrieved November 22, 2012.

- ^ Swanson, August. "The Douglas A/B-26 Invader Film Stars", napoleon130.tripod.com.[unreliable source?] Retrieved April 20, 2011.

- ^ Evans 2000, p. 187.

- ^ "The Train (1964)". IMDb.

- ^ Buford 2000, p. 240.

- ^ Balio 1987, p. 279.

- ^ "Most Popular Film Star", The Times, December 31, 1965, p. 13 via The Times Digital Archive, September 16, 2013.

- ^ "The 38th Academy Awards (1966) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1965". BAFTA. 1965. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "1965 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

Bibliography edit

- Armstrong, Stephen B. Pictures About Extremes: The Films of John Frankenheimer. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2007. ISBN 978-0-78643-145-8.

- Balio, Tino. United Artists: The Company That Changed the Film Industry. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1987. ISBN 978-0-29911-440-4.

- Buford, Kate. Burt Lancaster: An American Life. New York: Da Capo, 2000. ISBN 0-306-81019-0.

- Champlin, Charles, ed. John Frankenheimer: A Conversation With Charles Champlin. Bristol, UK: Riverwood Press, 1995. ISBN 978-1-880756-09-6.

- Evans, Alun. Brassey's Guide to War Films. Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books Inc., 2000. ISBN 978-1-57488-263-6.

- Pratley, Gerald. The Cinema of John Frankenheimer (The International Film Guide Series). New York: Zwemmer/Barnes, 1969. ISBN 978-0-49807-413-4

External links edit

- The Train at IMDb

- The Train at the TCM Movie Database

- The Train at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Train at AllMovie