The House on Carroll Street is a 1988 American neo-noir film[1] directed by Peter Yates, and starring Kelly McGillis, Jeff Daniels, Mandy Patinkin, and Jessica Tandy. Set in 1950s New York City, it follows a photojournalist who, blacklisted after refusing to disclose names to a 1951 House Un-American Activities Committee, stumbles upon a plot to smuggle Nazi war criminals into the United States.

| The House on Carroll Street | |

|---|---|

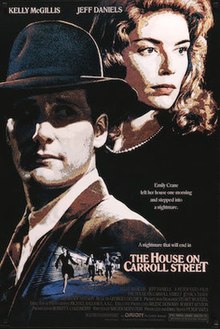

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Peter Yates |

| Written by | Walter Bernstein |

| Produced by | Peter Yates Robert F. Colesberry |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Michael Ballhaus |

| Edited by | Ray Lovejoy |

| Music by | Georges Delerue |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 101 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $14 million |

| Box office | $459,824 |

Plot edit

Emily Crane, a picture editor for Life magazine, is fired after refusing to give names to a 1951 House Un-American Activities Committee. She then takes a part-time job as companion/reader to an elderly woman. One day she overhears a noisy argument in a neighboring house. Outside, she eavesdrops through an open window. One of the occupants is the committee's main Senate prosecutor, Ray Salwen. The elderly man he is talking to speaks only German; a younger man named Stefan, whom Emily had earlier asked for directions, is interpreting their confrontation.

Emily meets Stefan on the street again and attempts to press him for information. When he rebuffs her, she follows him to a cemetery, where he demands to know why she is interested. They arrange to meet later a book shop, but are accosted by two US Immigration agents, panicking Stefan. He and Emily escape their pursuit; but before Stefan can tell Emily more, he is murdered by a knife-wielding assassin. During the crime scene investigation, the police find a list of four names in Stefan's pocket, and Emily insists that they search the house where she overheard the argument.

The police are skeptical of Emily's story, so she decides to search the house herself; the assassin reappears, but is thwarted by FBI agent Cochran, who has been keeping an eye on Emily for several days. After a scuffle, the assassin flees, and Cochran takes Emily home — but not before she picks up a book with a woman's name and a date written inside the cover. Cochran and his partner, Hackett, deduce that the name is actually that of a ship, which will be arriving in the Port of New York City the next day. Cochran and Emily observe the ship's arrival, but the intrigue grows when Cochran notes government officials present to receive some of the passengers.

Rather than take immediate action, Emily and Cochran follow the passengers to a wedding reception, where Emily recognizes the man who had the heated argument with Salwen — only he now speaks fluent English and introduces himself as Teperson, one of the names on Stefan's list. Emily slips away, eavesdrops on another conversation and learns that the group will be leaving on a train for Chicago the next evening. This time, she is intercepted by bodyguards and taken to a restaurant where Salwen is waiting to meet her.

Cochran, meanwhile, views a series of intelligence photographs featuring the men who are named on the list; they are all Nazi war criminals traveling under false names, being smuggled into the United States to participate in top-secret anti-Soviet scientific programs. Salwen cryptically reveals as much to Emily, who returns home to find Cochran trying to disarm a bomb rigged to her kitchen stove. They escape Emily's apartment seconds before the bomb explodes, and though Cochran is removed from the investigation, Emily goes to Grand Central Terminal to catch the party before their departure.

Cochran disobeys orders and meets Emily at the station; the assassin makes another attempt on Emily, but is subdued by Cochran and Hackett. Outrunning Salwen's other henchmen, Emily is finally cornered by Salwen in the framework of the station's ceiling, where he makes one last attempt to convince her of the greater good of the smuggling operation. When he tries to restrain her physically, she kicks him off a catwalk, whereupon Salwen crashes through the ceiling and falls to his death.

Cochran and Emily board the train carrying the criminals in the nick of time, where Cochran places the entire party under arrest. He loudly reveals to the other people on the train that Teperson is actually a physician who performed deadly experiments on prisoners at Auschwitz. Case closed, Emily returns to her part-time job as Cochran informs her that he is being transferred to Butte, Montana, and it is unlikely that they will see each other again.

Cast edit

- Kelly McGillis as Emily Crane

- Jeff Daniels as Cochran

- Mandy Patinkin as Ray Salwen

- Jessica Tandy as Miss Venable

- Jonathan Hogan as Alan

- Remak Ramsay as Senator Byington

- Ken Welsh as Hackett

- Christopher Buchholz as Stefan

Release edit

Box office edit

Released theatrically on March 4, 1988, The House on Carroll Street was a box-office bomb, grossing $459,824.[2] It was the second-worst performing film at the box office in 1988 after Distant Thunder.[3][4]

Critical reception edit

The reception for the film was mixed. Roger Ebert, film critic of the Chicago Sun-Times liked the film, especially the acting, and wrote "As thriller plots go, The House on Carroll Street is fairly old-fashioned, which is one of its merits. This is a movie where casting is important, and it works primarily because McGillis, like Ingrid Bergman in Notorious, seems absolutely trustworthy. She becomes the island of trust and sanity in the midst of deceit and treachery. The movie advances slowly enough for us to figure it out along with McGillis (or sometimes ahead of her), and there is a nice, ironic double-reverse in the fact that the government is following a good person who seems evil, and discovers evil people who seem good."[5][6]

Janet Maslin, film critic for The New York Times, gave the film a mixed review: "Mr. Yates does his best to make The House on Carroll Street a stylish period thriller, but its more ambitious scenes get away from him. A chase through a bookstore is monotonously staged, and the piece de resistance — a battle across the upper reaches of Grand Central Terminal — becomes noticeably clumsy. Even such showy gestures as having Salwen describe the Red Menace by pouring ketchup onto a white tablecloth manage to lack visual flair, not to mention political sophistication. It hardly helps that whenever the plucky Emily is doing her eavesdropping, she's able to overhear something much too convenient, like 'You'll be leaving on the Chicago Express, which departs at 6 o'clock.'"[7]

Frederic and Mary Ann Brussat, film critics at Spirituality & Practice, also gave the film a mixed review, writing "Although The House on Carroll Street lacks dramatic punch, the filmmakers deserve credit for raising moral issues involved in recruiting former Nazis to secure America's scientific lead over the Russians in the Cold War."[8]

Awards edit

The film won the award for Best Film at Mystfest in Italy in 1988.[9] Mystfest "focuses on the mystery film genre."[10]

Discography edit

The CD soundtrack composed by Georges Delerue is available on Music Box Records label (website).

References edit

- ^ Schwartz 2005, p. 120.

- ^ "The House on Carroll Street". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 5, 2022.

- ^ Klady, Leonard (January 8, 1989). "Box Office Champs, Chumps : The hero of the bottom line was the 46-year-old 'Bambi'". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on December 4, 2012.

- ^ Sickels 2008, p. 162.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 4, 1988). "The House on Carroll Street". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (March 4, 1988). "Reviews: The House on Carroll Street". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 2023-12-09.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (March 4, 1988). "Movie Review: The House on Carroll Street (1988)". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2016.

- ^ Brussat, Frederic and Mary Ann (2009). "The House on Carroll Street film review". Retrieved March 11, 2010.

- ^ "Mystfest: 1988 Awards". IMDb. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

- ^ "Mystfest". IMDb. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

Sources edit

- Sickels, Robert, ed. (2008). The Business of Entertainment. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-0-275-99838-7.

- Schwartz, Robert (2005). Neo-Noir: The New Film Noir Style from Psycho to Collateral. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-810-85676-9.