The Book of the Hanging Gardens (German: Das Buch der hängenden Gärten), Op. 15, is a fifteen-part song cycle composed by Arnold Schoenberg between 1908 and 1909, setting poems of Stefan George. George's poems, also under the same title, track the failed love affair of two adolescent youths in a garden, ending with the woman's departure and the disintegration of the garden. The song cycle is set for solo voice and piano. The Book of the Hanging Gardens breaks away from conventional musical order through its usage of atonality.

| The Book of the Hanging Gardens | |

|---|---|

| by Arnold Schoenberg | |

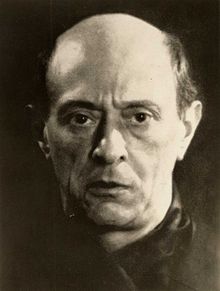

Portrait of Arnold Schoenberg by Man Ray, 1927 | |

| Native name | Das Buch der hängenden Gärten |

| Opus | 15 |

| Genre | Song cycle |

| Style | Free atonality |

| Text | The Book of the Hanging Gardens by Stefan George |

| Language | German |

| Composed | 1908–1909 |

| Duration | about 30 minutes |

| Movements | 15 songs |

| Scoring | Soprano and piano |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 14 January 1910 |

| Location | Vienna |

| Performers | Martha Winternitz-Dorda (soprano) Etta Werndorf (piano) |

The piece was premiered by Austrian singer Martha Winternitz-Dorda and pianist Etta Werndorf on January 14, 1910, in Vienna.

Biographical and cultural context edit

The Book of the Hanging Gardens served as the start to the atonal period in Schoenberg's music. Atonal compositions, referred to as "pantonal" by Schoenberg,[1] typically contain features such as a lack of central tonality, pervading harmonic dissonance rather than consonance, and a general absence of traditional melodic progressions. This period of atonality became commonly associated with the expressionist movement, despite the fact that Schoenberg rarely referred to the term "expressionism" in his writings.[citation needed] Whether or not he wanted to be associated with the movement, Schoenberg expresses an unambiguous positivity with his discovery of this new style in a program note for the 1910 first performance of The Book of the Hanging Gardens:

With the [Stefan] George songs I have for the first time succeeded in approaching an ideal of expression and form which has been in my mind for many years. Until now I lacked the strength and confidence to make it a reality. I am being forced in this direction ... not because my invention or technique is inadequate, but [because] I am obeying an inner compulsion, which is stronger than any upbringing. I am obeying the formative process which, being the one natural to me, is stronger than my artistic education.[2]

Schoenberg's libretto transcends the tragic love poems of George and become a deeper reflection of Schoenberg's mood during this period when viewing his personal life. The poems tell of a love affair gone awry without explicitly stating the cause of its demise. In 1908, Schoenberg's wife Mathilde left him and their two children for Richard Gerstl, a painter with whom Schoenberg was a close friend and for whom Mathilde often modeled. She returned to the family from her flight with Gerstl eventually, but not before Schoenberg discovered the poems of George and began drawing inspiration from them.

Structure edit

Although the 15 poems do not necessarily describe a story or follow a linear development, the general subjects can be grouped as follows: a description of the paradise (poems 1 and 2), the paths that the lover takes to reach his beloved (poems 3–5), his passions (poems 6–9), the peak of the time together (poems 10–13), premonition (poem 14), and finally, love dies away and Eden is no more (poem 15).[3]

First line of each poem (Original German)[4] Approximate English translation 1 Unterm Schutz von dichten Blättergründen Under the shade of thick leaves 2 Hain in diesen Paradiesen Groves in this paradise 3 Als Neuling trat ich ein in dein Gehege As a novice, I entered your enclosure 4 Da meine Lippen reglos sind und brennen Because my lips are motionless and burning 5 Saget mir auf welchem Pfade Tell me on which paths 6 Jedem Werke bin ich fürder tot To everything else I am henceforth dead 7 Angst und Hoffen wechselnd sich beklemmen Fear and hope alternately oppress me 8 Wenn ich heut nicht deinen Leib berühre If I today do not touch your body 9 Streng ist uns das Glück und spröde Strictness to us is happiness, and brittle 10 Das schöne Beet betracht ich mir im Harren I looked at the beautiful [flower] bed while waiting 11 Als wir hinter dem beblümten Tore As we behind the flowered gates 12 Wenn sich bei heilger Ruh in tiefen Matten If it with sacred rest in deep mats 13 Du lehnest wider eine Silberweide You lean against a white willow 14 Sprich nicht mehr von dem Laub Say no more of the foliage 15 Wir bevölkerten die abend-düstern Lauben We occupied the night-gloomy arcades

Critical reception edit

Upon its initial debut in 1910, The Book of the Hanging Gardens was not critically acclaimed or accepted in mainstream culture. Hanging Gardens' complete lack of tonality was initially disdained. Although a limited number of his works, including The Book of the Hanging Gardens, had been played in Paris since 1910, there was little attention from the French press for Schoenberg's music in general.[5] The reviews received elsewhere were usually scathing. One New York Times reviewer in 1913 went so far as to call Schoenberg "A musical anarchist who upset all of Europe."[6]

Deemed the Second Viennese School, Schoenberg and his students Anton Webern and Alban Berg helped to make Hanging Gardens and works like it more acceptable.[7] By the 1920s, a radical shift had occurred in the French reception of Schoenberg, his Hanging Gardens, and atonality in general. "For progressives, he became an important composer whose atonal works constituted a legitimate form of artistic expression."[5]

Critical analysis edit

Alan Lessem analyzes the Book of the Hanging Gardens in his book Music and Text in the Works of Arnold Schoenberg. However, how to interpret the work remains debated. Lessem maintained that the meaning of the song cycles lay in the words, and one critic finds his proposed relation of words and music fits Hanging Gardens better than the other songs treated in his book, and speculates that this may be because the theory was originally inspired by this cycle.[8] Lessem treats each interval as a symbol: "cell a provides material for the expression of poignant anticipations of love, cell b of frustrated yearnings" ...the structure of [the] cycle may, viewed as a whole, give the impression of progression through time, but this is only an illusion. The various songs give only related aspects of a total, irredeemable present."[9]

Moods are conveyed though harmony, texture, tempo, and declamation. The 'inner meaning,' if in fact there is to be found, is the music itself, which Lessem already described in great detail.[10]

Anne Marie de Zeeuw has examined in detail the "three against four" rhythm of the composition's opening and its manifestation elsewhere in the work.[11]

The garden as a metaphor edit

As argued in Schorske's groundbreaking study of Viennese society, the Book of the Hanging Gardens uses the image of the garden as a metaphor of the destruction of traditional musical form. The garden portrayed in George's poem, which Schoenberg puts to music, represent the highly organized traditional music Schoenberg broke away from. Baroque geometric gardens made popular during the Renaissance were seen as an "extension of architecture over nature." So too did the old order of music represent all that was authority and stable. The destruction of the garden parallels the use of rationality to break away from the old forms of music.[7]

References edit

- ^ Dudeque, Norton (2005). Music Theory and Analysis in the Writings of Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951). Aldershot, Hants, England: Ashgate. p. 116. ISBN 0754641392. OCLC 60715162.

- ^ Reich 1971, 48; also quoted in Brown 1994, 53.

- ^ "Program Notes & Translations (for Sept. 15, 1999)". Notes Countdown. University of Michigan. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ Charles Stratford (27 June 2023). "15 Gedichte aus Das Buch der hängenden Gärten von Stefan George für eine Singstimme und Klavier Op. 15 (1907–1909)" (in English and German). Austria: Arnold Schönberg Center. Retrieved 18 February 2024.

- ^ a b Médicis 2005, 576

- ^ Huneker 1913.

- ^ a b Schorske 1979, 344–364

- ^ Evans 1980, 36.

- ^ Lessem 1979, 42, 58.

- ^ Puffett 1981, 405.

- ^ de Zeeuw 1993.

Sources edit

- Brown, Julie (March 1994). "Schoenberg's Early Wagnerisms: Atonality and the Redemption of Ahasuerus". Cambridge Opera Journal. 6 (1): 51–80.

- de Zeeuw, Anne Marie (1993). "A Numerical Metaphor in a Schoenberg Song, Op. 15, No. XI". The Journal of Musicology. 11 (3): 396–410. doi:10.2307/763966. JSTOR 763966.

- Evans, Richard (March 1980). "[Review of Lessem 1979]". Tempo (132): 35–36.

- Huneker, James (19 January 1913). "Schoenberg, Musical Anarchist Who Has Upset Europe". Magazine section part 5. The New York Times. p. SM9.

- Lessem, Alan Philip (1979). Music and Text in the Works of Arnold Schoenberg: The Critical Years, 1908–1922. Studies in Musicology 8. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Research Press. ISBN 0-8357-0994-9 (cloth); ISBN 0-8357-0995-7 (pbk).

- Médicis, François de (2005). "Darius Milhaud and the Debate on Polytonality in the French Press of the 1920s". Music & Letters. 86 (4): 573–591.

- Puffett, Derrick (July–October 1981). "[Review of Lessem 1979]". Music & Letters. 62 (3): 404–406.

- Reich, Willi (1971). Schoenberg: A Critical Biography. Translated by Leo Black. London; New York: Longman; Praeger. ISBN 0-582-12753-X. Reprinted 1981, New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-76104-1

- Schorske, Carl (1979). Fin-de-siècle Vienna: Politics and Culture (1st ed.). New York; London: Knopf; Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 0-394-50596-4.

Further reading edit

- Dick, Marcel (1990). "An Introduction to Arnold Schoenberg's The Book of Hanging Gardens, op. 15". In Studies in the Schoenbergian Movement in Vienna and the United States: Essays in Honor of Marcel Dick, edited by Anne Trenkamp and John G. Suess, 235–239. Lewiston, New York: Mellen Press. ISBN 0-88946-449-9

- Domek, Richard C. (Fall 1979). "Some Aspects of Organization in Schoenberg's Book of the Hanging Gardens, opus 15". College Music Symposium 19, no. 2: 111–128.

- Dümling, Albrecht (1981). Die fremden Klänge der hängenden Gärten. Die offentliche Einsamkeit der Neuen Musik am Beispiel von A. Schoenberg und Stefan George. Munich: Kindler. ISBN 3-463-00829-7

- Dümling, Albrecht (1995). "Öffentliche Einsamkeit: Atonalität und Krise der Subjektivität in Schönbergs op. 15". In Stil oder Gedanke? Zur Schönberg-Rezeption in Amerika und Europa, edited by Stefan Litwin and Klaus Velten. Saarbrücken: Pfau-Verlag.

- Dümling, Albrecht (1997): "Public Loneliness: Atonality and the Crisis of Subjectivity in Schönberg's Opus 15". In: Schönberg and Kandinsky. An Historic Encounter, edited by Konrad Boehmer, 101-138. Amsterdam: Harwood Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-5702-047-5

- Schäfer, Thomas (1994). "Wortmusik/Tonmusik: Ein Beitrag zur Wagner-Rezeption von Arnold Schönberg und Stefan George". Die Musikforschung 47, no. 3:252–273.

- Smith, Glenn Edward (1973). Schoenberg's 'Book of the Hanging Gardens': An Analysis. DMA diss. Bloomington: Indiana University, 1973.

External links edit

- The Book of the Hanging Gardens: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project

- Das Buch der hängenden Gärten in Stefan George: Die Bücher der Hirten- und Preisgedichte, der Sagen und Sänge und der hängenden Gärten. Complete works, vol. 3, Berlin 1930