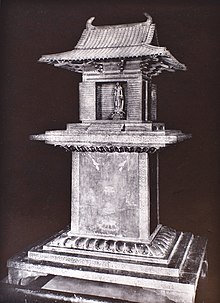

The Tamamushi Shrine (玉虫厨子, Tamamushi no zushi) is a miniature shrine owned by the Hōryū-ji temple complex of Nara, Japan. Its date of construction is unknown, but estimated to be around the middle of the seventh century.[2] Decorated with rare examples of Asuka-period paintings, it provides important clues to the architecture of the time[2][3] and has been designated a National Treasure.[4]

Consisting of a low rectangular dais supporting a plinth upon which stands a miniature building 233 centimetres (7 ft 8 in) tall, the Tamamushi Shrine derives its name from the iridescent wings of the tamamushi beetle with which it was once ornamented, but which have now exfoliated.[2] In spite of what its name in English may suggest, the shrine is not a miniature Shinto shrine, as zushi (厨子) is a term for a miniature shrine that houses Buddhist images or sūtra scrolls,[5] in this case a statue of Kannon and small rows of seated bronze Buddhas.[2]

History edit

The precise date of the shrine is uncertain, but it is generally placed around the middle of the seventh century.[2] A terminus ante quem is provided by the first documentary evidence for its existence, an inventory in temple records dating to 747, which includes "two items taking the form of a palace building, one with a design of a Thousand Buddhas in repoussé metalwork" (宮殿像弐具 一具金埿押出千佛像), understood to refer to the Tamamushi Shrine, the other being the later Tachibana Shrine.[6] A fuller description is given by the monk Kenshin in his account of the 1230s or 40s of Shōtoku Taishi, prince, regent, culture hero closely associated with the early promotion of Buddhism in Japan, and founder of the temple. He refers to the shrine's tamamushi wings and states that originally it belonged to Empress Suiko (d. 628).[6] Fenollosa, who helped implement the 1871 Plan for the Preservation of Ancient Artifacts through nationwide survey, concluded that it was presented to the Japanese Empress in the 590s.[7] Japanese scholar Uehara Kazu, who has written twenty-eight articles about the shrine over the course of nearly four decades and authored an extensive monograph, has conducted comparative analyses of architectural features and decorative motifs such as the tiny niches in which the Thousand Buddhas are seated.[8] Based on such considerations, the shrine is now dated either to c.650 or to the second quarter of the seventh century.[2][9][8]

Perhaps originally housed elsewhere, the shrine escaped the 670 Hōryū-ji fire.[10] Early accounts of the temple and its treasures see it placed on the great altar of the kondō.[6] Kenshin in the early Kamakura period mentions that it faced the east door and that its original Amida triad had at some point been stolen.[6][11] The shrine was still standing on the altar when Fenollosa was writing early in the twentieth century and is located there also in Soper's studies of 1942 and 1958.[12][13][7] Ernest Fenollosa describes the shrine along with the statue he uncovered at Hōryū-ji known as the Yumedono Kannon as "two great monuments of sixth-century Corean Art".[7] It is referred to by the authors of The Cambridge History of Japan as one of the "great works of Asuka art created by foreign priests and preserved as Japanese national treasures".[14] Domestic production under foreign influence is now the received wisdom.[2][8]

Evidently it escaped the major fire in the kondō on 26 January 1949 - the building was undergoing dismantling for restoration at the time and all portable items had already been removed.[15] (The damage to Hōryū-ji's celebrated wall paintings led to an overhaul of legislation relating to the preservation of the Cultural Properties of Japan.)[15] The shrine's shibi had already been detached, placed in the treasure hall, and replaced with copies.[12] Today the Tamamushi Shrine is exhibited in the temple's Great Treasure House.[9]

Architectural form edit

While the ground plan of many structures that are no longer extant is known, this miniature building is particularly important not only for its early date but also for the understanding it provides of the upper members, in particular the roof system, tiling, and brackets.[2] Few buildings survive from before the Nara period and, even for those that do, the roofs have been rebuilt several times.[15] The best if not only source for the earliest styles are miniature models such as the Tamamushi Shrine and, for the following century, the miniature pagodas from Kairyūō-ji and Gangō-ji.[16]

The miniature building has been identified variously as a palace-style building[2] and as a temple "golden hall" or kondō.[9] It has a hip-and-gable roof in the style known as irimoya-zukuri, or more precisely a variant of the type, known as shikorobuki (錏葺). In this technique, the hip and gable are clearly distinguished, with the latter overhanging the notably flat former and there is a distinct break in the tiling.[16][12] When Shitennō-ji was rebuilt after its destruction in the Pacific War, the roofing of the kondō retained this ancient style.[16][17] Ornamenting both ends of the ridgepole that runs the length of the top of the roof are curved tiles known as shibi, found in surviving eighth-century architecture only on the Tōshōdai-ji kondō.[9][18] The roof tiles are of the lipless, semi-circular type.[2][19] In the triangular field at each gable end is a "king-post", supporting the end of the ridgepole.[13][20] Descending the length of the gable and perpendicular to the main ridgepole are kudarimune (降り棟, or descending ridges).[16][21] Edging the gable beyond the descending ridges are "hanging tiles" or kakegawara (掛瓦), laid at right angles to both the other tiles and the descending ridges and projecting slightly to afford a degree of shelter (were this building not a miniature) to the bargeboards that help define the gable.[16][22]

The radiating brackets and blocks that support the deep eaves of the roof are "cloud-shaped" (kumo tokyō (雲斗栱, lit. cloud tokyō)), a type found only in the earliest buildings to survive to the modern period: the kondō, pagoda, and central gate (chūmon) at Hōryū-ji, and the three-storey pagodas at Hokki-ji and Hōrin-ji (the last was struck by lightning and burnt to the ground in 1944).[9][23] The bracket system supports tail rafters (尾垂木, odaruki) that extend far into the eaves. In a full-scale building, the downward load of the eaves upon the far end of these tail rafters is counterbalanced at the other end by the main load of the roof.[16][24] The simple unjointed purlins that support the roof covering in the eaves are circular in cross-section, as opposed to the rectangular purlins of the earliest surviving buildings.[12][25] Also at the corners the purlins are arranged parallel to each other rather than in the radial setting known from excavations at Shitennō-ji.[2] The columns or square posts are encased by their tie beams rather than pierced by the more usual penetrating tie beams (貫, nuki).[12][26]

Paintings edit

Japanese sculpture of the period was heavily influenced by Northern Wei and later sixth-century Chinese prototypes.[9] Details in the paintings such as the "flare" of the drapery, the cliffs and plants have also been likened to Wei art and that of the Six Dynasties.[2][10] The figures on the doors, the Guardian Kings and bodhisattvas, may be closer to more contemporary Chinese styles.[9] The handling of narrative in the Indra scene and that of the Tiger Jātaka, where spatial progression is used to represent that of time, may be found in the paintings of Cave 254 at Mogao.[9][27] At the same time it foreshadows that of later Japanese picture scrolls.[1]

Paintings on Buddhist themes cover all four sides of both building and plinth. While both pigmented and incised images are known from a number of tombs of a similar date, the shrine is the only example of Buddhist painting from early seventh-century Japan.[9][28] The closest domestic pictorial parallel is with embroideries such as the Tenjukoku Mandala from neighbouring Chūgū-ji, which shows Sui and Korean influence.[2][29] The description below can be followed in the linked images.

Standing on the front doors of the miniature building are two of the Four Guardian Kings, clad in armour, with flowing draperies, holding slender halberds; their heads are ringed with aureolae or Buddhist haloes.[2] On the side doors are bodhisattvas standing on lotus pedestals, their heads crowned with three mani jewels, holding a flowering lotus stalk in one hand and forming a mudrā or ritual gesture with the other.[2] The mudrā is a variant of the aniin (安慰印) or seppōin (説法印), the palm turned in and the thumb and index finger forming a circle (see Wheel of the Law), which according to the Sutra of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas symbolizes their thought of consoling all sentient beings.[30] The side panels flanking the doors are adorned with flowers and jewels.[2] On the back panel is a sacred landscape, with four caves in which Buddhist monks are seated, its heights topped with three pagodas.[2] Either side of the central mountain is a phoenix and apsara or tennin (celestial being), riding on clouds. At the top are the sun and the moon. This may be a representation of Mount Ryoju, where Shaka preached the Lotus Sutra.[2]

On the front of the plinth, below a pair of tennin, are two kneeling monks holding censers before a sacred vessel of burning incense; below are Buddhist relics; the vessel at the bottom is flanked on either side by lions.[2] On the back of the plinth is another sacred landscape, the central mountain topped by a palace and supporting a pair of small palaces on either side. At the foot is a dragon and beneath it a palace with a seated figure. In the side zones are phoenix, celestial beings, jewels, the sun and the moon. It is understood that this landscape depicts Mount Sumeru, the central world-mountain, the hatching at the bottom representing the seas.[2][9] On the right panel of the plinth is a scene from the Nirvana Sutra. At the bottom, while the Buddha is undergoing ascetic training in the mountains, Indra on the right appears before him in the guise of a demon. After hearing half a verse of the scriptures, the Buddha offered to cast away his body to the flesh-eating demon for the remainder. Before doing so, in the middle tier of the painting, the Buddha inscribes the teachings on the rocks. He then casts himself down from the summit, whereupon he is caught mid-plummet by Indra on the right in his true guise.[2][31] On the left panel of the plinth is the so-called Tiger Jātaka, an episode from the Golden Light Sutra, of a bodhisattva removing his upper garments and hanging them on a tree before casting himself from a cliff to feed a hungry tigress and her cubs.[2]

-

Front door guardians

-

Upper back with mountains

-

Lower front

-

Lower right

-

Lower back

Other decoration edit

The shibi or fishtail-like ornaments at either end of the ridgepole are shaped with stylized scales or feathers, while the front doors of the shrine, on its long side, are approached by means of a small flight of steps.[2][12] The architectural members of the building and edges of the plinth and dais are ornamented with bronze bands of "honeysuckle arabesque".[1] The base of the building and the dais at the very foot of the shrine exhibit the shape known as 格狭間 (kōzama) resembling an excised bowl that is common on later furniture, altar platforms and railings.[12][32] The plinth is surrounded, top and bottom, with mouldings of sacred lotus petals.[2]

The serial Buddhas that line the doors and walls inside the miniature building are in the iconographic tradition of the Thousand Buddhas.[1][33] Sūtras on the Buddha names such as the Bussetsu Butsumyōkyō, first translated into Chinese in the sixth century, may be related to the practice of Butsumyō-e or invocation of the names of the Buddha.[34] According to this text, which invokes the names of 11,093 Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Pratyekabuddhas, "if virtuous men and women receive and keep and read the names of the Buddhas, in the present life they shall have rest and be far from all difficulties, and they shall blot out all their sins. They shall obtain perfect wisdom in the future".[34] The continental practice of fo ming (佛名), or naming the Buddhas, from which the Japanese practice derived is believed to lie behind such representations of the Thousand Buddhas as the paintings of the Northern Wei Cave 254 at Mogao near Dunhuang; in this same cave there are also paintings of the Tiger Jātaka.[27]

Technology edit

The shrine is made of lacquered hinoki or Japanese cypress and camphor wood.[1] Both are native species.[9] Attached to the members of the building and the edges of plinth and dais are bands of openwork bronze. It was under this metalwork that the tamamushi wings were applied in the technique known as beetlewing.[2] The tamamushi beetle, a species of jewel beetle, is also native to Japan. The Thousand Buddhas are of repoussé or hammered bronze and the roof tiles are also of metal.[7] Optical microscopy or instrumental analysis, ideally non-invasive, would be needed to identify conclusively the pigments and binder used in the original colour scheme - red, green, yellow, and white on a black ground.[35] The range of available pigments, compared with that evident in the early decorated tumuli, was transformed with the introduction of Buddhism to Japan.[36][37] The precise medium in which the pigments are bound is uncertain.[35] While commonly referred to as lacquer, since the Meiji period some scholars have argued instead that the paintings employ the technique known as mitsuda-e, an early type of oil painting, using perilla (shiso) oil with litharge as a desiccant.[35][38]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d e Bunkazai Hogo Iinkai, ed. (1963). 国宝 上古, 飛鳥·奈良時代, 西魏·唐 [National Treasures of Japan I: Ancient times, Asuka period, Nara period, Western Wei, Tang] (in Japanese and English). Mainchi Shimbunsha. p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y Mizuno Seiichi (1974). Asuka Buddhist Art: Horyuji. Weatherhill. pp. 40–52.

- ^ "Tamamushi no zushi". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "玉蟲厨子" [Tamamushi Shrine]. Agency for Cultural Affairs. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Zushi". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ a b c d Uehara Kazu (1991). 玉虫厨子 飛鳥・白鳳美術様式史論 [Tamamushi-no-Zushi Shrine in Hōryū-ji Temple: a Study of Art in the Asuka-Hakuhō Period, Focussing on their Stylistic Features] (in Japanese). Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. pp. 122–4. ISBN 4-642-07300-0.

- ^ a b c d Fenollosa, Ernest F (1912). Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art: An Outline History of East Asiatic Design. Heinemann. p. 49.

- ^ a b c Uehara Kazu (1991). 玉虫厨子 飛鳥・白鳳美術様式史論 [Tamamushi-no-Zushi Shrine in Hōryū-ji Temple: a Study of Art in the Asuka-Hakuhō Period, Focussing on their Stylistic Features] (in Japanese). Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. pp. 1 f., passim. ISBN 4-642-07300-0.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Mason, Penelope E. (2004). History of Japanese Art (2nd (paperback) ed.). Prentice Hall. pp. 65, 74–81. ISBN 978-0-13-117601-0.

- ^ a b Stanley-Baker, Joan (1984). Japanese Art. Thames & Hudson. pp. 32. ISBN 978-0-500-20192-3.

- ^ Wong, Dorothy C., ed. (2008). Hōryūji Reconsidered. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-84718-567-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g Soper, Alexander Coburn (1942). The Evolution of Buddhist Architecture in Japan. Princeton University Press. pp. 104, 110, 113–5, 121.

- ^ a b Paine, Robert Treat; Soper, Alexander Coburn (1981). The Art and Architecture of Japan. Yale University Press. pp. 33–5, 316. ISBN 0-300-05333-9.

- ^ Brown, Delmer, ed. (1993). The Cambridge History of Japan. Cambridge University Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0-521-22352-2.

- ^ a b c Larsen, Knut Einar (1994). Architectural Preservation in Japan. ICOMOS. pp. 26, 111.

- ^ a b c d e f Parent, Mary Neighbour (1983). The Roof in Japanese Buddhist Architecture. Weatherhill. pp. 55, 62, 67, 227. ISBN 0834801868.

- ^ "Shikorobuki". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Shibi". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Gyougibuki gawara". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Shinzuka". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Kudarimune". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Kakegawara". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Kumotokyou". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Odaruki". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Hitonoki (cf. Futanoki)". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Nuki". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ a b Abe, Stanley K. (1989). Mogao Cave 254: a case study in early Chinese Buddhist art (PhD dissertation). University of California, Berkeley.

- ^ 装飾古墳データべース [Decorated Tomb Database] (in Japanese). Kyushu National Museum. Archived from the original on 16 August 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "The Tenjukoku Shucho Mandara". Tokyo National Museum. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ Saunders, Ernest Dale (1960). Mudrā: A Study of Symbolic Gestures in Japanese Buddhist Sculpture. Princeton University Press. pp. 66–75. ISBN 0-691-01866-9.

- ^ "The Mahayana Mahaparinirvana Sutra" (PDF). Shabkar.org. pp. 197–200. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ^ "Kouzama". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ "Sentaibutsu". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ^ a b De Visser, M. W. (1935). Ancient Buddhism in Japan, I. Brill. pp. 377–93.

- ^ a b c Uehara Kazu (1991). 玉虫厨子 飛鳥・白鳳美術様式史論 [Tamamushi-no-Zushi Shrine in Hōryū-ji Temple: a Study of Art in the Asuka-Hakuhō Period, Focussing on their Stylistic Features] (in Japanese). Yoshikawa Kōbunkan. pp. 395–401. ISBN 4-642-07300-0.

- ^ Kuchitsu Nobuaki (2007). "Impact of the introduction of Buddhism on the variation of pigments used in Japan". In Yamauchi Kazuya (et al.) (ed.). Mural Paintings of the Silk Road: Cultural Exchanges between East and West. Archetype. pp. 77–80. ISBN 978-1-904982-22-7.

- ^ Yamasaki Kazuo; Emoto Yoshimichi (1979). "Pigments used on Japanese Paintings from the Protohistoric Period through the 17th Century". Ars Orientalis. 11: 1–14.

- ^ "Mitsuda-e". Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. Retrieved 12 March 2012.

External links edit

- Introduction to the Tamamushi Shrine (The Saylor Foundation)

- (in Japanese) CiNii for articles about Tamamushi Zushi (search term: 玉虫厨子)