Steamboat Bill, Jr. is a 1928 silent comedy film starring Buster Keaton. Released by United Artists, the film is the final product of Keaton's independent production team and set of gag writers.

| Steamboat Bill, Jr. | |

|---|---|

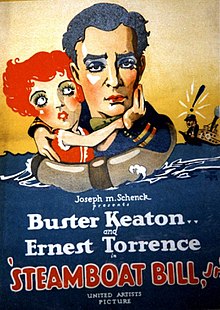

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by |

|

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Carl Harbaugh |

| Produced by | Joseph M. Schenck |

| Starring | Buster Keaton |

| Cinematography |

|

| Edited by | Sherman Kell (uncredited) |

| Distributed by | United Artists |

Release date |

|

Running time | 71 minutes (7 reels) |

| Country | United States |

| Languages | Silent film English intertitles |

The film was not a box-office success and became the last picture Keaton made for United Artists. Keaton ended up moving to Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, where he made one last film in his trademark style, The Cameraman, before his creative control was taken away by the studio.

Charles Reisner directed the film, and the credited story writer was Carl Harbaugh. The film, named after Arthur Collins's popular 1911 recording of the 1910 song "Steamboat Bill", also featured Ernest Torrence, Marion Byron, and Tom Lewis. The film is known for what may be Keaton's most famous film stunt: The facade of a house falls around him while he stands in the precise location of an open window to avoid being flattened.

In 2016, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress. The copyright of the film expired in 1956.[a]

Plot edit

William "Steamboat Bill" Canfield is the owner and captain of a paddle steamer, the Stonewall Jackson, that has seen better days. The King, a new steamer owned by the rich J. J. King, threatens to steal his customers. Canfield receives a telegram saying his son is arriving on the 10 am train, having finished his studies in Boston. Canfield has not seen him for many years.

King's daughter Kitty arrives home from college to visit him.

Canfield meets Bill Jr. at the train station, but is deeply disappointed with his slight, awkward son, who is wearing a foppish beret and has a pencil moustache and a ukulele. Canfield sends him to the barber to have the moustache removed, and there the young man bumps into Kitty, whom he knows from college.

Both Canfield and King are determined to break up the developing relationship between Bill Jr. and Kitty, but Bill Jr. slips off and boards the King at night. Canfield sees Bill Jr.'s clumsy and rebellious effort and buys him a ticket back to Boston. Kitty is angry at him for planning to leave and snubs him on the street.

When Canfield's ship is condemned as unsafe, he accuses King of orchestrating it. He assaults his enemy and is put in jail, prompting the son to tear up his train ticket. Bill Jr. makes a clumsy attempt to help his father escape, but ends up being knocked out by the sheriff and sent to the hospital.

A cyclone hits, demolishing buildings and endangering the ships. The hospital walls are torn away, leaving Bill Jr. exposed. As he makes his way through the town, a building front falls all around him as an unbroken facade, but Bill Jr. is untouched due to a fortunately placed open window. The jail is knocked off its foundations and starts to sink, with Canfield trapped inside. Bill Jr. rescues Kitty, Canfield, and King. Then he jumps into the water and comes back towing a minister in a lifebelt.

Cast edit

- Buster Keaton as William Canfield Jr.

- Ernest Torrence as William "Steamboat Bill" Canfield Sr.

- Marion Byron as Kitty King

- Tom McGuire as John James King

- Tom Lewis as Tom Carter

- Joe Keaton as the barber

Production edit

The original idea for the film came from Charlie Chaplin collaborator Charles Reisner, who was the director. Keaton, who had directed or co-directed many of his earlier films, was an uncredited co-director on this project.[1] In June 1927, he traveled to Sacramento, California, and spent over $100,000 building sets, including a pier. Original plans called for an ending with a flood sequence, but due to the devastating 1927 Mississippi River Flood, producer Joseph Schenck forced him to cut the arrangement.[1] Keaton also spent an additional $25,000 for the cyclone scene, which included breakaway street sets and six powerful Liberty-motor wind machines. The cyclone scene cost one-third of the film's entire budget, estimated at between $300,000 and $404,282.[2] Keaton, who planned and performed his own stunts himself, was suspended on a cable from a crane, which hurled him from place to place as if airborne.

Shooting began on July 15, 1927, in Sacramento. Production was delayed when Keaton broke his nose in a baseball game.

The film includes his most famous stunt: an entire building facade falling all around him. An open attic window fits neatly around Keaton's body as the structure falls, saving him from injury. He had performed a similar, though less elaborate, stunt in his earlier short films Back Stage (1919) and One Week (1920).[3] He used a genuine, two-ton building facade and no trickery. The mark on the ground showing Keaton exactly where to stand to avoid being crushed was a nail. It has been claimed that if he had stood just inches off the correct spot, he would have been seriously injured or killed.[4] His third wife, Eleanor, suggested that he took such risks due to despair over financial problems, his failing first marriage, the imminent loss of his filmmaking independence, and recklessness due to his worsening alcohol abuse at the time.[4] Evidence that Keaton was suicidal is scant—he was known throughout his career for performing dangerous stunts independent of any difficulties in his personal life, including a fall from a railroad water tower tube in 1924's Sherlock Jr. in which his neck was fractured.[5] He later said, "I was mad at the time, or I would never have done the thing." He also said that filming the shot was one of his greatest thrills.[6]

It is one of the few Keaton films to reference his fame. At the time of filming, he had stopped wearing his trademark pork pie hat with a short flat crown. During an early scene in which his character tries on a series of hats (something that was copied several times in other films), a clothing salesman briefly puts the trademark cap on his head, but he quickly rejects it, tossing it away.

At the end of shooting, Schenck announced the dissolution of Buster Keaton Productions.[3]

Reception edit

Steamboat Bill, Jr. was a box office failure[7] and received mixed reviews upon its release. Variety described the film as "a pip of a comedy" and "one of Keaton's best".[8] The reviewer from The Film Spectator appointed it "as perhaps the best comedy of the year thus far" and advised, "exhibitors should go after it".[9] A less enthusiastic review from Harrison's Reports stated, "there are many situations all the way through that cause laughs" while noting that "the plot is nonsensical".[10] Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times called the film a "gloomy comedy" and a "sorry affair".[11]

Over the years, Steamboat Bill, Jr. has become regarded as a masterpiece of its era. On Rotten Tomatoes 96% of critics have given the film a positive rating based on 52 reviews, with an average score of 9.00/10.[12] The film was included in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.[13]

Legacy edit

The film likely inspired the title of Walt Disney's Steamboat Willie (1928), which was released six months later and is considered the debut of Mickey Mouse.[14]

The famous falling house stunt has been re-created several times on film and television (although with lighter materials and more contemporary safety measures in place) including the 1975 The Goodies episode "The Movies", the 1991 MacGyver episode "Deadly Silents"; Jackie Chan's Project A Part II; the 2004 Arrested Development episode "The One Where They Build a House" (performed by the show's character named Buster); Al Yankovic's music video Amish Paradise (cross-referencing Peter Weir's 1985 film Witness); the 2006 comedy film Jackass Number Two; an Australian home insurance TV advertisement in 2021; and episode 7 in the first season of Lucha Underground, with a ladder.

Deadpan, a 1997 work by English film artist and director Steve McQueen, was also inspired by Steamboat Bill, Jr. McQueen stands in Keaton's place as a house facade falls over him. This film was shot from multiple angles, and the scene repeats over and over again while McQueen stands seemingly unaffected.[15]

George Miller's 1987 film The Witches of Eastwick references the scene where crates are blown all over Buster during the cyclone when Jack Nicholson gets debris (including boxes) blown over him in the windstorm sequence towards the end. The shot from the Keaton film is also seen in one of the multiple TVs in the media room in the final scene.

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ a b Meade 1997, p. 175.

- ^ Meade 1997, p. 176.

- ^ a b Meade 1997, p. 179.

- ^ a b Uytdewilligen, Ryan (2016). The 101 Most Influential Coming-of-age Movies. Algora Publishing. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-62894-194-4.

- ^ Gehring, Wes D. (2018). Buster Keaton in His Own Time: What the Responses of 1920s Critics Reveal. McFarland. pp. 367–. ISBN 978-1-4766-3326-8.

- ^ Meade 1997, p. 180.

- ^ Meade 1997, p. 182.

- ^ "Variety Reviews - Steamboat Bill, Jr.". Variety. May 16, 1928. Archived from the original on November 7, 2012. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "Steamboat Bill, Jr.". The Film Spectator. June 23, 1928. Retrieved January 31, 2011 – via silentsaregolden.com.

- ^ "Steamboat Bill, Jr.". Harrison's Reports. May 26, 1928. Retrieved January 31, 2011 – via silentsaregolden.com.

- ^ Hall, Mordaunt (May 15, 1928). "THE SCREEN; A Gloomy Comedy". The New York Times. p. 17. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- ^ "Steamboat Bill, Jr". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ "1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die". Listology. Archived from the original on July 15, 2016. Retrieved June 3, 2020.

- ^ Korkis, Jim. "Secrets of Steamboat Willie". Mouse Planet. Retrieved November 5, 2014.

- ^ "Steve McQueen. Deadpan. 1997". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ As a work governed exclusively under the 1909 Copyright Act, its copyright expired 28 years from publication since the copyright was not renewed.

- Bibliography

- Meade, Marion (1997). Buster Keaton: Cut to the Chase (1st ed.). New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80802-1.

External links edit

- Steamboat Bill, Jr. at IMDb

- Steamboat Bill, Jr. is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- Steamboat Bill, Jr. at AllMovie

- Steamboat Bill, Jr. at the TCM Movie Database

- Steamboat Bill, Jr. at the International Buster Keaton Society

- Choice clips from this Public Domain classic (in Windows and Real Media format)