Shoot the Piano Player (French: Tirez sur le pianiste; UK title: Shoot the Pianist) is a 1960 French New Wave crime drama film directed by François Truffaut that stars Charles Aznavour as the titular pianist with Marie Dubois, Nicole Berger, and Michèle Mercier as the three women in his life. It is based on the novel Down There by David Goodis.

| Shoot the Pianist | |

|---|---|

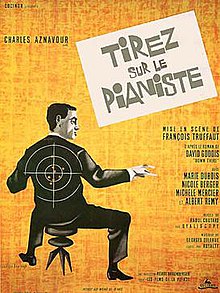

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | François Truffaut |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | Down There 1956 book by David Goodis |

| Produced by | Pierre Braunberger |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Raoul Coutard |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Georges Delerue |

Production company | Les Films de la Pléiade |

| Distributed by | Les Films du Carrosse |

Release date |

|

Running time | 81 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Budget | ₣890,062.95 |

| Box office | 974,833 admissions (France)[1] |

In the film, a professional pianist learns that he owes his entire career to his wife's affair with a talent agent. Following his wife's suicide, the widower starts using a pseudonym and finds work in a bar. When his brothers steal the loot of gangsters, the pianist and his new love interest are targeted for kidnapping.

Plot edit

In Paris, Édouard Saroyan hits rock bottom after his wife Thérèse confesses that his career as a concert pianist is due to her having slept with a top agent, and when he fails to respond, she kills herself. Under the assumed name of Charlie Koller, he now strokes the keys in Plyne's bar, and when she has no clients, he spends the rest of the night with Clarisse, a prostitute who cooks for his little brother Fido.

Léna, the bar's waitress, is falling in love with Charlie, and she secretly knows his true identity. When his two older brothers steal the loot of a pair of gangsters,[2] the gangsters abduct Charlie and Léna, who escape through Léna's quick thinking. Léna takes him to her room, where they make love. The gangsters then abduct Fido, who reveals his brothers' mountain hideout.

Léna realises that the gangsters traced Charlie and Fido through Plyne, who wants to sleep with her and who is jealous of Charlie's luck. In a confrontation at the bar, Charlie accidentally kills Plyne, and Léna then smuggles him from Paris to the mountain hideout. Léna is killed in a shoot-out when the gangsters arrive with Fido.

Differences from novel edit

The film shares the novel's bleak plot about a man hiding from his shattered life by doing the only thing he knows how to do while remaining unable to escape the past. However, Truffaut's work resolves itself into both a tribute to the American genre of literary and cinematic film noir and a meditation on the relationship between art and commercialism.[citation needed]

Truffaut significantly changes Charlie's personality. Originally, Goodis's Edward Webster Lynn (whom Truffaut adapts as Charlie) is "pictured as a relatively strong, self-confident guy who has chosen his solitude [whereas] Truffaut’s Charlie Kohler has found his isolation inevitably; he was always shy, withdrawn, reclusive".[3]

Cast edit

- Charles Aznavour as Charlie Koller / Edouard Saroyan

- Marie Dubois as Léna

- Nicole Berger as Thérèse Saroyan

- Michèle Mercier as Clarisse

- Serge Davri as Plyne

- Claude Mansard as Momo

- Richard Kanayan as Fido Saroyan

- Albert Rémy as Chico Saroyan

- Jean-Jacques Aslanian as Richard Saroyan

- Daniel Boulanger as Ernest

- Claude Heymann as Lars Schmeel

- Alex Joffé as Passerby

- Boby Lapointe as The Singer

- Catherine Lutz as Mammy

Production edit

Background and writing edit

Truffaut first read David Goodis's novel in the mid-1950s while shooting Les Mistons when his wife Madeleine Morgenstern read it and recommended it to him.[4] He immediately loved the book's dialogue and poetic tone and showed it to producer Pierre Braunberger, who bought the rights.[5] Truffaut later met Goodis in New York City, and the novelist gave Truffaut a vintage viewfinder from his brief experience as a second unit director on a U.S. film.[6]

Truffaut said he made the film in reaction to the success of The 400 Blows, which he considered to be very French. He wanted to show his influence from American films.[5] He later told a reporter that he wanted to shock the audience that had loved The 400 Blows by making a film that would "please the real film nuts and them alone."[7] He previously had several ideas for films about children, but was afraid of repeating himself in his second film. He told a reporter "I refused to be a prisoner of my own first success. I discarded temptation to renew that success by choosing a "great subject". I turned my back on what everyone waited for and I took my pleasure as my only rule of conduct."[7]

Truffaut began writing the script with Marcel Moussy, who had co-written The 400 Blows. Moussy said that he didn't understand the book and attempted to establish clear social roots for the characters. Truffaut disagreed, wanting to keep the film loose and abstract; Moussy left after a few weeks, and Truffaut wrote the script himself.[8] One problem Truffaut had was that he considered the Goodis novel to be too chaste, and he decided to make the characters less heroic.[9] The book's main character Charlie is also much stronger in the book, and Truffaut called it a Sterling Hayden type. Truffaut decided to go the opposite direction and make the protagonist weaker and the female characters strong. Truffaut was influenced by French writer Jacques Audiberti while writing the film, such as in his treatment of the character Plyne.[10] Truffaut also used some scenes from other Goodis novels, such as the early scene where Chico bumps into a lamppost and has a conversation with a stranger.[11]

Casting edit

Truffaut had wanted to work with Charles Aznavour since seeing him act in Georges Franju's Head Against the Wall and wrote the role with Aznavour in mind.[12] Child actor Richard Kanayan had appeared in The 400 Blows and was always making the crew laugh, so Truffaut cast him as Charlie's youngest brother. Nicole Berger was an old friend of Truffaut's and also Pierre Braunberger's stepdaughter. Michèle Mercier was a dancer who had appeared in a few films before this role. Albert Remy had appeared in The 400 Blows and Truffaut wanted to show the actor's comedic side after his performance in the previous film. Truffaut also cast actor and novelist Daniel Boulanger and theatrical actor Claude Mansard as the two gangsters in the film.[13] Serge Davri was a music hall performer who had for years recited poems while breaking dishes over his head. Truffaut considered him crazy, but funny, and cast him as Plyne. Truffaut rounded out the cast with Catherine Lutz in the role of Mammy. Lutz had never acted before and worked at a local movie theater.[11]

Truffaut first noticed Marie Dubois when he came across her headshot during pre-production and attempted to set up several meetings with the actress, but Dubois never showed up. Truffaut finally saw Dubois perform on a TV show and immediately wanted to cast her shortly before filming began. Dubois's real name was "Claudine Huzé" and Truffaut changed it to Marie Dubois because she reminded him of the titular character of his friend Jacques Audiberti's novel Marie Dubois. Audiberti later approved of the actress's new stage name.[13] Truffaut later told a reporter that Dubois was "neither a 'dame' nor a 'sex kitten'; she is neither 'lively' nor 'saucy'. But she's a perfectly worthy young girl with whom it's conceivable you could fall in love and be loved in return".[14]

Filming edit

Filming took place from 30 November 1959 until 22 January 1960 with some re-shoots for two weeks in March. Locations included a cafe called A la Bonne Franquette on the rue Mussard in Levallois, Le Sappey-en-Chartreuse, around Grenoble and throughout Paris.[15] The film's budget was 890,062.95 francs.[16] Whereas The 400 Blows had been a tense shoot for Truffaut, his second film was a happy experience for the cast and crew after Truffaut's first success.[11] Truffaut had wanted to make it as a big budget studio film, but was unable to get sufficient funds and the film was made on the streets instead.[17] Truffaut filled the film with homages to such American directors as Nicholas Ray and Sam Fuller.[18] During the shooting Truffaut realized that he didn't like gangsters and tried to make their character more and more comical.[13] Pierre Braunberger initially didn't like Boby Lapointe's songs and said that he couldn't understand what Lapointe was saying. This inspired Truffaut to add subtitles with a bouncing ball.[9]

Filming style edit

The film's script changed constantly during shooting. Truffaut said that "In Shoot the Piano Player I wanted to break with the linear narrative and make a film where all the scenes would please me. I shot without any criteria."[19]

Truffaut's stylized and self-reflexive melodrama employs the hallmarks of French New Wave cinema: extended voice-overs, out-of-sequence shots, and sudden jump cuts. The film's cinematography by Raoul Coutard was often grainy and kinetic, reflecting the emotional state of the characters, such as the scene in which Charlie hesitates before ringing a doorbell.[20]

Among the film references in Shoot the Piano Player are nods to Hollywood B movies from the 1940s, the iris technique from silent films, Charlie being named after Charlie Chaplin, and having three brothers (including one named Chico) as a reference to the Marx Brothers.[21] Moreover, the film's structure and flashbacks resemble the structure of Citizen Kane.[22] Truffaut later stated, "In spite of the burlesque idea to certain scenes, it's never a parody (because I detest parody, except when it begins to rival the beauty of what it is parodying). For me it's something very precise that I would call a respectful pastiche of the Hollywood B films from which I learned so much."[23] This was also Truffaut's first film to include a murder, which would become a plot point in many of his films and was influenced by Truffaut's admiration of Alfred Hitchcock.[24]

Truffaut stated that the theme of the film is "love and the relations between men and women"[25][18] and later claimed that "the idea behind Le Pianiste was to make a film without a subject, to express all I wanted to say about glory, success, downfall, failure, women and love by means of a detective story. It's a grab bag."[26] Like The 400 Blows, Shoot the Piano Player was shot in Dyaliscope, a widescreen process which Truffaut described as being like an aquarium that allows the actors to move around the frame more naturally.[27]

Soundtrack edit

- "Framboise" (Boby Lapointe) by Boby Lapointe

- "Dialogue d'Amoureux" (Félix Leclerc) by Félix Leclerc and Lucienne Vernay

Reception edit

Critical response edit

Shoot the Piano Player was first shown at the London Film Festival on 21 October 1960.[28] It later premiered in Paris on 22 November and in the U.K. on 8 December.[15] It did not premiere in the U.S. until July 1962.[28]

The film was financially unsuccessful, although it was popular among cinephiles such as Claude Miller. Miller was then a film student at IDHEC and later explained that he and his friends knew all the film's dialogue by heart, stating "We cited it all the time; it became a kind of "in" language."[29]

Film critic Marcel Martin called it a disappointment after The 400 Blows and wrote that it would "only please the true lover of movies."[30] In Variety, film critic Mosk called its script meandering[31] and Bosley Crowther wrote that the film "did not hold together."[32] Pauline Kael called Aznavour's performance "intensely human and sympathetic"[33] and Andrew Sarris praised the film, stating "great art can also be great fun."[34] Dwight Macdonald stated that the film mixes "three genres which are usually kept apart: crime melodrama, romance and slapstick...I thought the mixture didn't gel, but it was an exhilarating try."[35] Jacques Rivette initially complained to Truffaut that Charlie was "a bastard", but later stated that he liked the film.[9]

On Rotten Tomatoes, 90% of critics' reviews for Shoot the Piano Player are positive, with an average rating of 8.9/10.[36]

Awards and nominations edit

| Year | Award ceremony | Category | Nominee | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | Cahiers du cinéma | Annual Top 10 List | François Truffaut | 4th |

In popular culture edit

In Britain, the joke about the piano player does not derive from this film but from the alleged remark of Oscar Wilde on his 1882 American tour, while in the wild west: "Don't shoot the pianist, he is doing his best."[37] This is also the source of the book and film title. The line evidently gained some currency in popular European culture thereafter. For example, the French translation—"Ne tirez pas sur le pianiste, il fait ce qu'il peut"—appears written prominently in the wall décor of a nightclub in the 1933 Julien Duvivier detective film A Man's Neck.[38]

The title has become somewhat of a joke on the club scene, usually to get a less-than-talented musician to stop performing, but occasionally breaks into the musical mainstream:

- The phrase 'shoot-the-piano-player' was firmly in American culture at the start of the 20th century. The 1933 Vitaphone short sound film, "The Mild West," opens in a Wild West saloon with a trio of men singing, accompanied by a house pianist playing barroom songs. An on-looker at a poker game across the room asks the players, "How can you play with all that noise going on?" A gambler replies, "I can't," promptly draws a pistol, and shoots the piano player, who falls to the floor dead. The saloon owner, a Mae West knock-off named Lulu, admonishes the shooter: "Say, what's the big idea? Can't you read?" The camera cuts to a sign on the wall: 'Please Do Not Shoot the Piano Player' encircling a drawing of a man with his hands up behind an upright piano. A second piano player takes the place of the first at the piano and the singing resumes. A dandy, Gentleman Joe, enters, greets Lulu, then turns to shoot the new piano player, who falls dead. When Lulu admiringly watches Jim walk away, Baby Doll says, "I notice you don't say anything to him about shooting piano players," Lulu answers, "Ah, but he shoots them so genteel!" Finally, the piano on its own starts up the song again--it's a Player piano--and a lone singer starts to sing. When he sings a note off-key, in disappointment, he takes out a revolver and shoots himself dead.

- In the 1966 Howard Hawks film El Dorado, when Cole Thorton (John Wayne) and Mississippi (James Caan) stop to buy a shotgun for Mississippi, they ask the gunsmith Swede Larson where the shotgun came from, they are told that the previous owner was a man who couldn't see very well but got into a fight in a saloon. However, the shotgun owner couldn't hear the other man because the piano player was making too much noise, so "he just shoot the piano player and they hung him".

- British singer-songwriter Elton John turned the joke on its head by naming his 1973 album Don't Shoot Me I'm Only the Piano Player.

- In 1985, the band Miami Sound Machine used the joke in their video for "Conga". Whispering about how boring the ambassador's reception is, drummer Enrique Garcia says to singer Gloria Estefan "Let's shoot the fat guy on the piano!" She laughs, having no idea they'll be performing next.

- The 1991 party game Notability was played by people trying to guess a song played on a toy piano, while, according to the rules, "SHOOT THE PIANO PLAYER!" was to be shouted if someone thought the player was cheating (playing out of tune/tempo).

- This is one of Bob Dylan's favorite films and inspired his early work. Dylan refers to the film explicitly in "11 Outlined Epitaphs", which serve as the liner notes to his 1963 album The Times They Are a-Changin': "there's a movie called / Shoot the Piano Player / the last line proclaimin' / 'music, man, that's where it's at' / it is a religious line / outside, the chimes rung / an' they / are still ringin'" (spelling and punctuation as in the original).[39]

- Martin Scorsese said "the character played by Charles Aznavour in Shoot the Piano Player, who keeps almost acting but never does until it's too late, had a profound effect on me and on many other filmmakers."[40]

The 2002 film The Truth About Charlie was an homage to this film; references are made, a brief scene is shown, and Aznavour makes two appearances in the movie.

References edit

- ^ Box Office information for Francois Truffaut films at Box Office Story

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 35–110.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 203.

- ^ Wakeman, John. World Film Directors, Volume 2. The H. W. Wilson Company. 1987. pp. 1125.

- ^ a b Brunette 1993, pp. 119.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 123.

- ^ a b Brunette 1993, pp. 134.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 124.

- ^ a b c Brunette 1993, pp. 122.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 132.

- ^ a b c Brunette 1993, pp. 127.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 131.

- ^ a b c Brunette 1993, pp. 125.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 130.

- ^ a b Brunette 1993, pp. 33.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 126.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 142.

- ^ a b Brunette 1993, pp. 129.

- ^ Wakeman. pp. 1125.

- ^ Insdorf 1995, p. 24.

- ^ Insdorf 1995, p. 26.

- ^ Insdorf 1995, p. 3334.

- ^ Brunette 1993, p. 5.

- ^ Insdorf 1995, p. 44.

- ^ Insdorf 1995, pp. 107.

- ^ Insdorf 1995, pp. 27.

- ^ Brunette 1993, p. 120.

- ^ a b Brunette 1993, pp. 34.

- ^ Wakeman. pp. 1125.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 145.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 148.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 159.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 155.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 156.

- ^ Brunette 1993, pp. 9.

- ^ "Shoot the Piano Player". Rotten Tomatoes. 25 November 1960. Retrieved 10 February 2023.

- ^ "Oscar Wilde - Wilde in America". Today in Literature. 9 March 2014. Archived from the original on 9 March 2014. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ^ Duvivier, Julien, director. (1933). La Tête d'un homme. Paris: Produced by Marcel Vandal and Charles Delac.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Times They Are A-Changin' | The Official Bob Dylan Site". www.bobdylan.com. Retrieved 17 April 2021.

- ^ Scorsese, Martin (13 November 2006). "François Truffaut". Time. Archived from the original on 13 December 2006. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

Further reading edit

- Baecque, Antoine de; Toubiana, Serge (1999). Truffaut: A Biography. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0375400896.

- Bergan, Ronald, ed. (2008). François Truffaut: Interviews. Oxford: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 978-1934110133.

- Brunette, Peter (1993). Shoot the Piano Player: François Truffaut, director. New Brunswick and London: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-1941-1.

- Insdorf, Annette (1995). François Truffaut. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521478083.