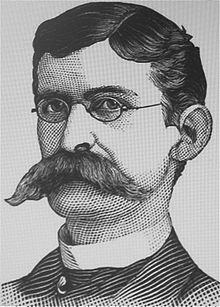

Samuel White "Sam" Small (July 3, 1851 – November 21, 1931) was a journalist, Methodist evangelist, and prohibitionist.

Samuel White Small | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 3, 1851 |

| Died | November 21, 1931 (aged 80) |

| Resting place | Arlington National Cemetery |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Emory & Henry College |

| Occupation | Journalist |

| Employer | Atlanta Constitution |

| Known for | Evangelist, prohibitionist |

| Political party | Democratic, Prohibition, Populist |

| Spouse | Annie Isabelle Arnold |

| Children | 3 |

Youth edit

Small was born on a plantation near Knoxville, Tennessee, the son of Alexander B. Small, a newspaper editor and president of an express company.[1] Small later said of his childhood that he was "well born … given by kindly parents all the true and religious culture that a boy could have in a loving home."[2] At thirteen Small enlisted in the reserves of the Confederate Army during the last months of the war.[3] He graduated from high school in New Orleans[4] and then attended Emory & Henry College, graduating in 1871. He immediately began a career in journalism even while toying with becoming a lawyer. In 1873, he married Annie Isabelle Arnold, and they had a daughter and two sons.[5]

Early career edit

The influence of his father secured Small a position as secretary to former President Andrew Johnson. In 1878, President James Garfield appointed Small secretary to the United States commissioner general of the Paris Exposition of 1878. Despite his other interests, Small retained an "obsession for politics," and near the end of his life he boasted of having "clasped hands with every president from James Buchanan to Herbert Hoover."[6]

Small contributed to the Atlanta Constitution a series of dialect sketches under the persona of an old black man, "Old Si," stories that gained him a national reputation.[7] Unfortunately, Small had by this time descended into alcoholism, and when he was unable to continue, editor Evan Howell asked Joel Chandler Harris to try his hand at similar material.[8]

Evangelist and prohibitionist edit

In September 1885, while working as a court stenographer and freelance reporter, Small covered a revival meeting of evangelist Sam Jones in Cartersville, Georgia. There Small was so "overwhelmed by conviction of sin" that on arriving back in Atlanta, he immediately started drinking.[9] Nevertheless, four days after visiting Cartersville, Small "pleaded with Christ that he would let me cling to his cross, lay down all my burdens and sins there, and be rescued and saved by his compassion." Small's family at first feared he was slipping into madness.[10] Small soon began testifying to his deliverance from alcohol, and Sam Jones now came to hear him preach in Atlanta. "Small's fame and newspaper connections ensured that his conversion would garner publicity," and Jones invited Small to be his associate.[11]

Although Small's collaboration with Jones lasted only a few years, in part because of heavy debts Small had contracted while he was drinking,[12] Small interspersed his re-entrance into journalism with preaching, lecturing, and writing two books that advocated prohibition: Pleas for Prohibition (1889) and The White Angel of the World (1891).[13] In 1889, Small even considered becoming an Episcopal priest.[14]

Later career edit

Small founded the Oklahoma City Oklahoman (1889) and the Norfolk (VA) Pilot (1894).[15] Appointed a chaplain during the Spanish–American War, Small began an English language paper in Havana. In 1890 Small also unsuccessfully attempted to found a Methodist college in Ogden, Utah,[16] but he eventually found his way back to the editorial staff of the Atlanta Constitution by 1901.[17]

Small also lectured on behalf of the Anti-Saloon League.[18] In a florid address to the Anti-Saloon League's 1917 convention in Washington, DC, Small told the cheering crowd that if the United States enacted prohibition, "then you and I may proudly expect to see this America of ours, victorious and Christianized, become not only the savior but the model and the monitor of the reconstructed civilization of the world in the future."[19] Small also kept his hand in politics. In 1892 he ran for Congress as a prohibition-supporting Populist.[20]

In 1927, Bob Jones, Sr. asked Small to write a creed for the proposed Bob Jones College. The creed written quickly on the back of an envelope has been memorized and recited daily by generations of Bob Jones University students.[21]

By 1930, Small was the oldest active editor in the South and still wrote three columns of editorials a day.[22] Nevertheless, Small had been injured in a fall during the Republican National Convention of 1928, and he died in Atlanta on November 21, 1931. He was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.[23]

References edit

- ^ Kathleen Minnix, Laughter in the Amen Corner: The Life of Evangelist Sam Jones (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1993), 92.

- ^ Samuel W. Small, "Deliverance from Bondage: A Temperance Sermon," in Sam P. Jones and Sam Small, Living Words of Sam Jones' Own Book …(London: T. Woolmer, 1886), 573.

- ^ Thomas W. Herringshaw, The Biographical Review of Prominent Men and Women of the Day (Chicago: Home Publishing House, 1888), 179. Small was hardly a partisan of the "Lost Cause." In a temperance sermon of 1886, Small said that "misguided men in the South fired the first shot upon Fort Sumter. ... I tell you that whatever were the disasters of war, it struck the shackles from six million slaves." Samuel W. Small, "Deliverance from Bondage: A Temperance Sermon," in Sam P. Jones and Sam Small, Living Words of Sam Jones' Own Book …(London: T. Woolmer, 1886), 573.

- ^ Thomas W. Herringshaw, The Biographical Review of Prominent Men and Women of the Day (Chicago: Home Publishing House, 1888), 179.

- ^ New York Times, November 22, 1931.

- ^ Minnix, 92–93.

- ^ New York Times, February 17, 1886. Small's collected sketches were published as Old Si's Sayings F.H. Revell, 1886)

- ^ R. Bruce Bickely, Joel Chandler Harris: A Biography and Critical Study (University of Georgia Press, 2008)

- ^ Minnix, 93.

- ^ Small, "Deliverance from Bondage: A Temperance Sermon," 582. Small said that when he asked God to "remove from him entirely and forever this awful craving … the long-felt desire left him there and then," never to return.

- ^ Minnix, 93. Jones said, "God wouldn't have kicked up a bigger fuss in all Georgia if he had gone down and restored sight to a man born blind than He did when, two weeks ago, He touched Sam Small. I tell you this conversion is the talk of all Georgia." As Minnix has written, Small "represented the refined plantation South," while Jones tended toward the "uncouth, impulsive … humorous and sarcastic side of things." (94)

- ^ New York Times, August 1, 1886.

- ^ Who Was Who in America, I.

- ^ Atlanta Constitution, December 13, 1889. He had earlier taken steps toward the priesthood in his drinking days. (Minnix, 93)

- ^ Washington Post, April 15, 1895.

- ^ New York Times, September 8, 1890. According to an early history of Methodism in Utah, Small was selected as president of the proposed college by five of nine trustees who "held a hurried meeting June 1, 1890 on the platform of the Union Pacific depot at Ogden...without the knowledge or consent of the Physical Agent, Dr. T. C. Iliff. This hasty action caused friction, and the selection of Reverend Small proved to be a regrettable mistake. The work ceased as the pledges in Ogden failed to be paid as promised in the amount of eleven thousand dollars." Henry Martin Merkel, History of Methodism in Utah (Colorado Springs: Dentan Printing Co., 1938), 195-96.

- ^ Washington Post, December 28, 1901.

- ^ Fulton (NY) Evening News, May 25, 1916, 1.

- ^ James Timberlake, Prohibition and the Progressive Movement, 1900–1920 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963), 38.

- ^ Joe L. Coker, Liquor in the Land of the Lost Cause: Southern White Evangelicals and the Prohibition Movement (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2007), 102, 113.

- ^ Daniel L. Turner, Standing Without Apology: The History of Bob Jones University (Greenville, SC: BJU Press, 1997), 29.

- ^ Washington Post, July 7, 1930.

- ^ New York Times, November 22, 1931.