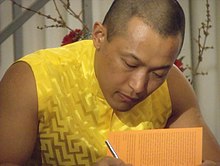

Sakyong Jamgon Mipham Rinpoche, Jampal Trinley Dradül (born Ösel Rangdrol Mukpo ca. November 15, 1962) is a Tibetan Buddhist lama and holder of the Sakyong Lineage of Mukpodong, a family lineage. The Sakyong was recognized in 1995 as the tulku (reincarnation) of Mipham the Great, the great Rime teacher of the late 19th century.

Mipham Rinpoche | |

|---|---|

| |

| Title | Sakyong |

| Personal | |

| Born | Ösel Rangdrol Mukpo ca. November 15, 1962, on the Full moon day of the tenth lunar month Bodh Gaya, India |

| Religion | Shambhala Training |

| Nationality | American, Tibetan |

| Spouse | Semo Tseyang Palmo Mukpo, nee Ripa aka Dechen Choying Sangmo |

| Children | 3 daughters: Jetsun Drukmo Yeshe Sarasvati Ziji Mukpo, Jetsun Yudra Lhamo Yangchen Ziji Mukpo, Jetsun Dzedrön Ökar Yangchen Ziji Mukpo |

| Lineage | Sakyong Lineage, Kagyü and Nyingma |

| Occupation | Author and Teacher, Tibetan Buddhism |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, Penor Rinpoche (aka. Pema Norbu Rinpoche), Namkha Drimed Rinpoche |

| Reincarnation | Mipham the Great |

| Sakyong Mipham | |||||

| Tibetan name | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tibetan | ས་སྐྱོང་མི་ཕམ་ | ||||

| |||||

The Sakyong led the Shambhala organization, a worldwide network of Buddhist meditation centers, retreat centers, a monastery, and other enterprises, from 1991 until 2021 when they parted ways.

He is the son of the renowned Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche.

In July 2018, after more than two decades at the helm Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche agreed to temporarily step back from his administrative and teaching duties to allow space for an investigation into allegations of sexual misconduct.[1] He resumed teaching in late 2019. He legally separated from the Shambhala organization in February 2022 after an impasse in which the Shambhala Board of Directors could not agree with the Sakyong Potrang - the organization representing the Sakyong - on a way forward together. He moved to Nepal and gives teachings to his international sangha most weekends online.[2]

Biography edit

Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche was born Ösel Rangdröl Mukpo in Bodhgaya, India about November 15, 1962, although his mother was not certain of the exact date.[3][4] His father, Chögyam Trungpa, was a Buddhist monk who fled Tibet in 1959 (at age 20). His mother, Könchok Paldrön, was a nun who met Trungpa in Tibet and was among the refugees who fled with him to India.[5] For several years, Mukpo lived with his mother Konchuk Paldron in a Tibetan refugee camp in northwest India.[5][6] His father left India in early 1963 to study at Oxford University.[6] At the age of seven, he went to live with his father at Samye Ling in Scotland.[5] Ösel was left at Samye Ling in the care of Akong Rinpoche when his father moved to North America. Later that year when Akong travelled to India, he left the boy in the care of Christopher and Pamela Woodman.[5][6] Diana Mukpo returned to retrieve the boy from the couple who were caring for him near Samye Ling but they refused to surrender him. Social Services took custody of young Ösel and he was moved to Pestalozzi Village, a boarding school for orphaned children established during WWII. He resided there until Social Services could conduct a home inspection in the US.[6] Young Ösel was released to his father's custody in 1972 after more than two years alone in Britain.[3][6]

Ösel Mukpo has two younger half-brothers by his father and Diana Mukpo, (Gesar Mukpo and Tagtrug "Taggie" Mukpo), a half-brother, Gyurme Dorje Onchen, by his mother "Lady" Konchuk Paldron and her husband Lama Pema Gyaltson, and two younger step-brothers (Ashoka Mukpo) and David Mukpo, sons of Diana Mukpo and Mitchell Levy.[5]

In 1979, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche performed a ceremony officially investing his son Ösel Rangdröl with the title of Sawang ("earth lord"). This confirmed Ösel as his Shambhala heir and the future Sakyong.[3]: 204 After his father's death in 1987, the Sawang began his studies with Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, in Nepal which continued until the Mahasiddah's death. At that time and at the instruction of Khyentse Rinpoche, Mukpo began his studies with Pema Norbu Rinpoche(Penor Rinpoche) in India where he attended Shedra at Namdrolling Monastery and continued to oversee the Vajradhatu community. The young Sakyong spent six months each year in the east in his studies, and six months in the west relating to the sangha.

When Trungpa Rinpoche's Regent Ösel Tendzin died in 1990, the 27-year-old Sawang was acknowledged by Jamgön Kongtrül Rinpoche and Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche as Trungpa's successor in the Kagyu, Nyingma and Shambhala lineages and head of the Vajradhatu organization.[3]: 410–411 Upon discovering that Trungpa Rinpoche had given the boy the name Mipham Lhaga, Penor Rinpoche recognized Mukpo as the tulku of Mipham the Great,[3]: 413 and in May 1995 he was formally enthroned as Sakyong. Since then he has been known by the title Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche.

In 2002 the Sakyong began running. His first marathon was Toronto in 2003.[7] He trained and ran in nine marathons, including Big Sur, Chicago, and the New York and Boston Marathons in 2005[8][9]

In 2005 the Sakyong met and married Semo Tseyang Palmo Ripa, daughter of the Tibetan Buddhist Rinpoche Terton Namkha Drimed Ripa, a Nyingma master and holder of the Ripa family lineage.[10] They first met when Penor Rinpoche invited the Gesar Lingdro dancers to perform at Namdroling monastery where the Sakyong was studying. The Sakyong's mother, Konchuk Paldron also knew the Ripa family, and had close ties to the bride's paternal uncle, though the Sakyong did not meet them until this time.[11]

In late 2008 and early 2009 the Sakyong received the Rinchen Terdzo, or the complete cycle of terma teachings of the Nyingma school of Buddhism from Namkha Drimed Rinpoche in Orissa, India.[12] This cycle of teachings had been given to Namkha Drimed Rinpoche by the Sakyong's father, Chogyam Trungpa in Tibet.

In 2009 he began teaching the Scorpion Seal terma, the highest teachings of the Shambhala lineage to more than two thousand students.[13] For the next several years he taught extensively on these deep teachings at the four Shambhala retreat centers, Shambhala Mountain Center in Colorado, Karme Choling, in Vermont, Dorje Denma Ling, in Nova Scotia, and Dechen Choling, in France. He continued to write and teach on this terma cycle until the summer of 2018.

In 2010 his first daughter, Jetsun Drukmo Yeshe Sarasvati Ziji Mukpo was born. The birth of their first child was also a year of deep retreat and writing for the Sakyong. The Sakyong's father had died at the age of 47, and so he marked this milestone by going into retreat in Nepal.

While on retreat he wrote volumes of practices and commentaries on the Buddhadharma and the Shambhala teachings of his father.[14] The Sakyong came out of retreat to teach, including giving an empowerment at Shambhala Mountain Center in the summer of 2010, and then returned to teaching full time in 2012.[15] Namkha Drimed Rinpoche also bestowed the Nyingma Kama empowerments on the Sakyong, which represent the oral transmission the Nyingma received from India from the time of their arrival in Tibet.

The Sakyong received the Gongter, or Mind Terma[16] of the Terton, Namkha Drimed Rinpoche in the fall of 2015.[17] This Gongter of Gesar of Ling teachings is the largest terma cycle of Gesar in the world.

Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche has written several books, including the national bestseller Turning the Mind into an Ally, Ruling Your World, Running with the Mind of Meditation, and The Shambhala Principle and The Lost Art of Conversation. His most recent book Garuda 108 Poems, was released in 2019. In 2018, he temporarily stepped back from all teaching and administrative duties to allow for an investigation and public discussion of his alleged sexual misconduct.[18] He resumed teaching with a small group of students in the Netherlands late in 2019, and then in March 2020, instructing a group of 108 students in Nepal.[19] His teachings have continued regularly in person and online since then. <[20]>

Controversies edit

After assuming the leadership of Vajradhatu in 1990, the Sakyong completed his training under the guidance of Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, and Penor Rinpoche. As he took his seat as Chödak [(Tib. ཆོས་བདག, Wyl. chos bdag), or custodian of a terma cycle] and holder of the Shambhala Terma cycle of his father, the Sakyong began moving the sangha to practice this cycle of teachings. He began by talking about the singularity of the Shambhala teachings and Buddhism, which had previously been taught separately. Shambhala Training had often been referred to as a "secular" path. In 2000, the Sakyong began talking about Shambhala Buddhism as a single entity and path, with no separation between spiritual and secular. In 2004 at Vajrayana seminary at Shambhala Mountain Center, the Sakyong received and introduced the Primordial Rigden Ngondro, titled the Magical Heart of Shambhala. The following year, he held the first Rigden Abhisheka, an empowerment to practice the vajrayana teachings of Shambhala. Later that year thangka painter Cynthia Moku, under the direction of the Sakyong released the first Thangka of the Primoridal Rigden deity. The changes to the Shambhala curriculum, and the introduction of the Shambhala teachings as a Buddhist path caused upheaval in the community. Many people believed the Sakyong misunderstood what his father, Chogyam Trungpa had intended with these teachings. There were many complaints about the replacement of the primary thangka of Vajradhara with the Primordial Rigden from the organization's meditation centers. The curriculum was ever changing as older programs initiated by Trungpa Rinpoche were replaced with shorter, more accessible programs. The Sakyong also stopped teaching the Kagyu teachings of his Father, which he held and had offered through the 1990s.

In 2009 the Sakyong sent a letter to the community providing guidelines and restrictions on inviting teachers from other lineages to teach at Shambhala Centers. This, he said, was to help us 'know who we are' as a community. Students saw this as another change from how his father had done things, and therefore suspect.

In response, older students began to migrate to other teachers who were teaching the Kagyu practices of his father. Many resented the direction he took the organization. By the time of #MeToo, older students had decided clearly that they were following the Shambhala Vajrayana, or had found other teachers.[21]

In 2018, Buddhist Project Sunshine, an organization founded as a survivors' network for former Shambhala members,[22] reported multiple allegations of sexual assault within the Shambhala community.[23][24][18] In response, and in order to allow time for the community to investigate these accusations, Sakyong Mipham temporarily stepped aside as leader, and the Shambhala governing council resigned and appointed an interim Board of Directors and "Process Team."[25][26][27] Sakyong Mipham issued a letter to the community saying that "...some of these women have shared experiences of feeling harmed as a result of these relationships. I am now making a public apology. In addition, I would like you to know that over the years, I have apologized personally to people who have expressed feeling harmed by my conduct, including some of those who have recently shared their stories. I have also engaged in mediation and healing practices with those who have felt harmed. Thus I have been, and will continue to be, committed to healing these wounds."[28][29] In July 2018, Naropa Institute removed him from their board following the allegations of sexual misconduct.[30]

In August 2018, Buddhist Project Sunshine released another report containing further allegations against Sakyong Mipham that included sexual encounters with minors,[31][32] a charge that the Sakyong has denied.[33] In December 2018, the Larimer County, Colorado Sheriff's Office opened an investigation of the allegations of sexual assault.[34][35] The investigation was closed in February 2020, and no charges were filed.[36] In February 2019, Shambhala International's interim governing council issued a report by Wickwire Holm, a Canadian law firm, that detailed two credible allegations of sexual misconduct against Sakyong Mipham.[37][38][39] Later that month, six members of his Kusung (body protectors) wrote an open letter corroborating a pattern of physical and sexual misconduct and other concerns.[40][41] Sakyong Mipham subsequently stated that he would cease teaching for the "foreseeable future".[42] He returned to teaching in March 2020, instructing a group of 108 students in Nepal.[19] In September 2020, The Walrus published an investigative report detailing a culture of abuse dating back to early days of the Shambhala Buddhist organization, with all three leaders of the organization, including its founder, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, having been credibly accused of sexual misconduct and abuse of power.[43]

Lineage of Sakyongs edit

The Lineage of Sakyongs is the Mukpo family lineage of Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche. The Sakyong is the second in the family to hold this title and has the responsibility of propagating the teachings of Shambhala. This tradition emphasizes confidence in the basic goodness of all beings and teaches courageous self-rulership based on wisdom and compassion. The term "Sakyong" literally means "earth-protector" in Tibetan. Sakyongs are regarded as chögyals (Sanskrit dharmarajas) – "kings of truth" or "Dharma Kings" – who combine the spiritual and worldly paths. This Shambhala path is specifically meant for lay practitioners.

In Tibetan Buddhism, the first Dharmaraja of Shambhala, Dawa Sangpo, was said to have been empowered directly by the Buddha. Dawa Sangpo recognized that he could not give up his throne and responsibilities in order to pursue the path of a monastic. Thus, he requested teachings that could allow him to continue to rule his kingdom, while practicing the dharma.

The Blazing Jewel of Sovereignty is the ritual empowerment for the Sakyong. Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche was the first in this lineage of Sakyongs to receive this empowerment. He is referred to as the "Druk Sakyong", or "Dragon Earth-Protector". He received this ritual empowerment from Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche in Boulder, Colorado [citation needed].

Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche was first empowered as "Sawang" by his father, Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche in 1979. The empowerment of the Blazing Jewel of Sovereignty was conferred upon him by his teacher Penor Rinpoche in May 1995[44]

In April 2023, this empowerment was bestowed upon Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche's eldest daughter, Jetsun Drukmo Rinpoche, who will succeed him as lineage heir.

Sakyong Wangmo and family edit

The consort of the Sakyong is referred to as the Sakyong Wangmo. The current Sakyong Wangmo is Sakyong Mipham's wife Khandro Tseyang Ripa Mukpo, the daughter of Terton Namkha Drimed Rabjam Rinpoche. The Sakyong and Sakyong Wangmo were married in a public ceremony on 10 June 2006 in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[45] Khandro Tseyang was officially empowered as Sakyong Wangmo by Penor Rinpoche at a ceremony in Halifax in August 2008.[46] The Sakyong and Sakyong Wangmo have three daughters. The first, Drukmo Yeshe Sarasvati Ziji Mukpo (Lady Dragon Wisdom), was born on 11 August 2010. The second, Jetsun Yudra Lhamo Yangchen Ziji Mukpo, was born 12 March 2013.[47] The third, Dzedrön Ökar Yangchen Ziji Mukpo, was born on 10 April 2015.[48]

Bibliography edit

Books edit

- Garuda: 108 Poems, Kalapa Publications, 2019

- The Lost Art of Good Conversation, Harmony Books, 2017, ISBN 9780451499431

- The Vow: Illuminating the Sun and Moon, Dragon, Shambhala Media, 2014

- The Shambhala Principle: Discovering Humanity's Hidden Treasure, Harmony Books, 2013, ISBN 0770437435

- The Supreme Thought: Bodhichitta and the Enlightened Society Vow, Dragon, Shambhala Media, 2013, ISBN 9781550550542

- Running with the Mind of Meditation: Lessons for Training Body and Mind, Harmony Books, 2012, ISBN 0307888169

- Treatise on Enlightened Society, Dragon, Shambhala Media, 2012, ASIN B082891BNL

- Ruling Your World: Ancient Strategies for Modern Life, Morgan Road Books, 2005, ISBN 0-7679-2065-1

- Snow Lion's Delight: 108 Poems, Vajradhatu Books, 2005, ISBN 9781550550221

- Turning the Mind into an Ally, Riverhead Books, 2004, ISBN 1-57322-345-X

- Taming the Mind and Walking the Bodhisattva Path, Vajradhatu Publications, 1999, ASIN B000JI0B9S

- Smile of the Tiger, Vajradhatu Books, 1998, ISBN 978-1550550115

Articles edit

- Mahayana Motivation in Lion's Roar, February 2, 2018.

- Why We Must Practice the Art of Good Communication in Tricycle Magazine, January 16, 2018.

- Path Through Obstacles in Lion's Roar, November 6, 2017.

- Slow Down You Move too Fast in Lion's Roar, August 20, 2017.

- How to Practice Mindfulness in Lion's Roar, July 28, 2017.

- The Myth of Permanence in Lion's Roar, June 13, 2017.

- Just Leap in Lion's Roar, June 10, 2017.

- It's Not Us and Them in Lion's Roar, June 3, 2017.

- Shamatha Meditation: Training the Mind in Lion's Roar, April 17, 2017.

- Going at Our Own Pace on the Path of Meditation in Lion's Roar, March 29, 2017.

- Confined by Cowardice in Lion's Roar, March 29, 2017.

- True Listening in Lion's Roar, October 14, 2016.

- Deep Seeing in Lion's Roar, September 2, 2016.

- Running Into Meditation in Lion's Roar, August 23, 2016 .

- A Simple Sense of Delight in Lion's Roar, June 3, 2016.

- Let it Shine in Lion's Roar, .May 25, 2016

- Obstacles on the Path in Shambhala Sun, July 13, 2014.

- Let Your Confidence Shine in Shambhala Sun,June 30, 2014.

- Who Are We, Really? in Shambhala Sun, May 1, 2014.

- The Great Vow in Shambhala Sun, September 1, 2013.

- The Great Reversal in Shambhala Sun, July 1, 2013.

- Are We Basically Good in Shambhala Sun, May 5, 2013.

- The Supreme Thought in Shambhala Sun, March 7, 2013.

- We Need to be Warriors in Shambhala Sun, November 15, 2012.

- The Power of Self-Reflection in Shambhala Sun, May 9, 2012.

- Stop, Relax, Wake Up in Shambhala Sun, January 19, 2012.

- Joined at the Heart in Shambhala Sun,November 29, 2011.

- In Sync in Shambhala Sun, August 2, 2011.

- Sunny Side Up in Shambhala Sun, May 24, 2011.

- Love and Emptiness in Shambhala Sun, November 17, 2010.

- Lost in Shambhala Sun, September 1, 2010.

- What Turns the Wheel in Shambhala Sun, July 19, 2010.

- Time to be Pragmatic in Shambhala Sun, May 1, 2010.

- How to be a Peacemaker in Shambhala Sun, March 1, 2010.

- Peace in the Fast Lane in Shambhala Sun, January 1, 2010.

- Ready, Steady, Go in Shambhala Sun, September 1, 2009.

- The Jewel You Carry with You. in Shambhala Sun, May 1, 2009.

- How Will I Use This Day? in Shambhala Sun, February 1, 2009.

- Contemplating Compassion in Shambhala Sun, July 1, 2008.

- There's No "I" in Happy in Shambhala Sun, March 1, 2007.

- From Seed to Bloom in Shambhala Sun, January 1, 2007.

- It's All in the Mind in Shambhala Sun, November 2006.

- Good Mind in Shambhala Sun, September 1, 2006.

- The Wish Fulfilling Jewel in Shambhala Sun, July 1, 2006

- The Mind of the Dragon and the Power of Non-Self in Shambhala Sun, November 1, 2005

- A Reign of Goodness in Shambhala Sun, September 1, 2005

- No Real Winners in Shambhala Sun, July 1, 2005

- Waves of Compassion in Shambhala Sun, May 1, 2005

- No Complaints in Shambhala Sun, November 1, 2004

- Harness the Wind in Shambhala Sun, September 1, 2004

- Make your Decisions for Others in Shambhala Sun, July 1, 2004

- Seeing Wisdom as the Essence of Phenomena in Shambhala Sun, May 1, 2004

- End Blame in Shambhala Sun, March 1, 2004

- Personal Practice in Shambhala Sun, January 1, 2004

- A Courageous Activity in Shambhala Sun, September 1, 2003

- A Healthy Sense of Self in Shambhala Sun, July 1, 2003

- Nine Stages to Training the Mind in Shambhala Sun, May 1, 2003

- Taking the First Step in Shambhala Sun, November 1, 2002

- Looking in All the Wrong Places in Shambhala Sun, September 1, 2002

- Riding the Energy of Basic Goodness in Shambhala Sun, July 1, 2002

- The Buddha's Bravery in Shambhala Sun, March 1, 2002

- The Great Stupa Which Liberates Upon Seeing in Shambhala Sun, January 1, 2002

- Take the Big View in Shambhala Sun, November 1, 2001

- Using the Power of Thought in Shambhala Sun, September 1, 2001

- Did You Hear? in Shambhala Sun, July 1, 2001

- Meditation and Post Meditation in Shambhala Sun, May 1, 2001

- Do I Exist or Not? in Shambhala Sun, March 1, 2001

- How We Make Ourselves Suffer in Shambhala Sun, January 1, 2001

- What is this Thing Called Mind in Shambhala Sun, November 1, 2000

- Becoming a Buddhist in Shambhala Sun, September 1, 2000

- Endless Migration in Shambhala Sun, July 1, 2000

- Wisdom in the Words in Shambhala Sun, March 1, 2000

- Meditation is the Practice of Being Alive in Shambhala Sun, July 1, 1994

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ Bundale, Brett (July 9, 2018). "Shambhala leader steps aside amid sexual misconduct allegations". CBC News.

- ^ "Teaching Schedule". SakyongLineage.org. Sakyong Lineage. Retrieved March 3, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Hayward, Jeremy (2008). Warrior-King of Shambhala: Remembering Chögyam Trungpa. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-546-6.

- ^ Mukpo, Mipham J. (2003). Turning the Mind into an Ally. New York, NY: Riverhead Books. pp. xii. ISBN 1-57322-345-X.

- ^ a b c d e Midal, Fabrice (2004). Chogyam Trungpa: His Life and Vision. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 9780834821866.

- ^ a b c d e Mukpo, Diana J. (2006). Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chögyam Trungpa. Boston: Shambhala Publications. ISBN 1-59030-256-7.

- ^ Moses, Michele (July 8, 2014). "I'm a Runner: Sakyong Mipham". Runner's World.

- ^ Schmidt, Michael S. "Lama Feels Spirit of City While Testing His Soles". New York Times. Retrieved November 7, 2005.

- ^ "The Sakyong by a mile". alexwright.com. April 21, 2005. Archived from the original on October 26, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- ^ Lowe, Lezlie (June 8, 2006). "Opinion: Big Love". The Coast. The Coast.

- ^ Shambhala News Service. "The Sakyong's Married". Shambhalasangha.livejournal.com.

- ^ Blaine, Walker (2011). The Great River of Blessings: The Rinchen Terdzo in Orissa, India. Halifax, NS: Highland Publications.

- ^ Wilton, James (January 21, 2009). "Shambhala and the Kagyu Lineage". radiofreeshambhala.org. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- ^ Thorpe, James (November 4, 2011). "The Sakyong in Deep Retreat". Shambhala Times.

- ^ "Shambhala Process Team History of teachings" (PDF).

- ^ "Mind terma". www.rigpawiki.org. Archived from the original on March 18, 2023. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

- ^ "Sakyong Gives Talk at Gongter". Ripa Ladrang.

- ^ a b "The 'King' of Shambhala Buddhism Is Undone by Abuse Report". The New York Times. July 11, 2018. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ a b "Rigden Nepal Pilgrimage March 8-15, 2020". Shambhala Report. April 16, 2020.

- ^ >https://sakyonglineage.org/sakyong-miphams-teachings/<

- ^ Cote, Benoit. "Twenty Years of Ruling and Teaching". Shambhala Times. Shambhala. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ "Buddhist Project Sunshine". andreamwinn.com. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Winn, Andrea M. "Project Sunshine: Final Report, February 27, 2017 –February 15, 2018" (PDF). andreamwinn.com. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Winn, Andrea M. (June 28, 2018). "Buddhist Project Sunshine Phase 2 Final Report" (PDF). andreamwinn.com. et al. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Kalapa Council. "Kalapa Council Quarterly Update". Shambhala.report. Shambhala. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ Bundale, Bret (July 9, 2018). "Shambhala Leader Steps Aside Amid Sexual Misconduct Allegations". The Canadian Press. CBC. Retrieved July 10, 2023.

- ^ O'Connor, Kevin (October 8, 2018). "Vermont Buddhists face their own MeToo moment". VTDigger. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ RInpoche, Sakyong Mipham. "Letter to the Community". Shambhala.report. Retrieved July 2, 2023.

- ^ Biddlecombe, Wendy Joan (June 28, 2018). "Shambhala head Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche accused of sexual abuse in new report". Tricycle. Retrieved July 11, 2018.

- ^ "Boulder's Naropa University removes Shambhala International leader from its board". Boulder Daily Camera. July 6, 2018. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Winn, Andrea M.; Merchasin, Carol (August 23, 2018). "Buddhist Project Sunshine Phase 3 Final Report; The nail: Bringing things to a clear point" (PDF). andreamwinn.com. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Agsar, Wendy Joan Biddlecombe (August 23, 2018). "Report Reveals New Sexual Assault Allegations Against Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche". Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Bundale, Brett (August 23, 2018). "Buddhist leader accused of sexual misconduct denies new allegations". CBC. CBC News. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Eaton, Joshua (December 9, 2018). "Colorado police investigating alleged sexual assaults by Buddhist leaders". ThinkProgress. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Barnett, Jackson (December 12, 2018). "Larimer County sheriff investigating "possible criminal activity" at Shambhala Mountain Center". The Denver Post. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Julig, Carina (February 18, 2020). "Larimer County Closes Investigation into Shambhala Mountain Center". The Denver Post. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Shambhala Interim Board (February 3, 2019). "Report to the Community on the Wickwire Holm Claims Investigation into Allegations of Sexual Misconduct". Document cloud. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Barnett, Jackson (February 3, 2019). "Shambhala report details sexual misconduct from Buddhist leader Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche". The Denver Post. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Bundale, Brett (February 4, 2019). "Report finds 'sexual misconduct' by leader of Buddhist group". CBC. CBC News. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Long-Serving Kusung (February 16, 2019). "An Open Letter to the Shambhala Community". drive.google.com. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ Bousquet, Tim (February 19, 2019). "Six former members of the Shambhala inner circle write an open letter detailing physical, sexual, and psychological abuse at the hands of Mipham Mukpo". Halifax Examiner. Retrieved February 24, 2019.

- ^ "Shambhala Buddhist leader drops teaching in wake of report on sexual misconduct". Estevan Mercury. February 21, 2019. Archived from the original on February 25, 2019.

- ^ "Survivors of an International Buddhist Cult Share Their Stories | The Walrus". September 28, 2020. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ "Sakyong Enthronement" (PDF). Vol. 10, no. 3. Snow Lion Publications. 1995.

- ^ Armstrong, Jane (June 3, 2006). "Heaven and Halifax at Buddhist "royal wedding"". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Bodley, Laurie (Winter 2008–2009). "The Sakyong Wangmo empowerment" (PDF). The Dot. 6 (3): 1, 6–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 6, 2013. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Brooks Arenburg, Patricia (March 13, 2013). "Halifax's Shambhala royal family welcomes second child". The Chronicle Herald. Retrieved July 30, 2014.

- ^ Watters, Haydn (April 13, 2015). "Shambhala Buddhist community's queen gives birth in Halifax". CBC News Nova Scotia. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

References edit

- Hayward, Jeremy (2008) Warrior-King of Shambhala: Remembering Chögyam Trungpa ISBN 0-86171-546-2