Roman Arkadyevich Abramovich (Russian: Роман Аркадьевич Абрамович, pronounced [rɐˈman ɐrˈkadʲjɪvʲɪtɕ ɐbrɐˈmovʲɪtɕ]; Hebrew: רומן ארקדיביץ' אברמוביץ'; born 24 October 1966)[1] is a Russian oligarch and politician. He is the former owner of Chelsea, a Premier League football club in London, England, and is the primary owner of the private investment company Millhouse.[2] He has Russian, Israeli and Portuguese citizenship.[3][4]

Roman Abramovich | |

|---|---|

| Роман Абрамович | |

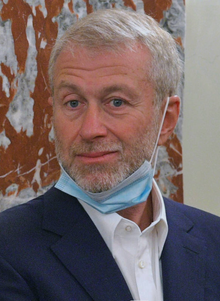

Abramovich in 2021 | |

| Governor of Chukotka | |

| In office 17 December 2000 – 3 July 2008 | |

| Preceded by | Aleksandr Nazarov |

| Succeeded by | Roman Kopin |

| Member of the State Duma from Chukotka constituency | |

| In office 10 January 2000 – 17 December 2000 | |

| Preceded by | Vladimir Babichev |

| Succeeded by | Vladimir Yetylin |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Roman Arkadyevich Abramovich 24 October 1966 Saratov, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (present-day Saratov, Russia) |

| Citizenship |

|

| Political party | Independent |

| Spouses | Olga Lysova

(m. 1987; div. 1990)Irina Malandina

(m. 1991; div. 2007) |

| Children | 7, including Arkadiy Abramovich |

| Education | Moscow State Law University Russian State University of Oil and Gas |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for |

|

| Awards | |

He was formerly Governor of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug from 2000 to 2008. According to Forbes, Abramovich's net worth was US$14.5 billion in 2021.[5] making him the second-richest person in Israel,[6][7] Since then, his wealth decreased to $6.9 billion (in 2022), and recovered up to $9.2 billion in 2023.[8] Abramovich enriched himself in the years following the collapse of the Soviet Union in the 1990s, obtaining Russian state-owned assets at prices far below market value in Russia's controversial loans-for-shares privatisation program. Abramovich is considered to have a good relationship with Russian president Vladimir Putin,[9] an allegation Abramovich has denied.[10]

Early life edit

Roman Arkadyevich Abramovich was born on 24 October 1966 in Saratov, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union (present-day Saratov, Russia). His mother, Irina (1939−1967), was a music teacher who died when Abramovich was one year old.[11] His father, Aaron Abramovich Leibovich (1937−1969), who was of Jewish descent,[12] worked in the economic council of the Komi ASSR,[13] and died when Roman was three.[11] Roman's maternal grandparents were Vasily Mikhailenko and Faina Borisovna Grutman, both born in Ukraine. It was to Saratov in the early days of World War II that Roman's maternal grandmother fled from Ukraine. Irina was then three years old.[14] Roman's paternal grandparents, Nachman Leibovich and Toybe (Tatyana) Stepanovna Abramovich, were Belarusian Jews.[14] They lived in Belarus and, after the revolution,[which?] moved to Tauragė, Lithuania,[15][16][17] with the Lithuanian spelling of the family name being Abramavičius.

In 1940, the Soviet Union (USSR) annexed Lithuania. Just before the Nazi German invasion of the USSR, the Soviets "cleared the anti-Soviet, criminal and socially dangerous element" with whole families being sent to Siberia. Abramovich's grandparents were separated when deported. The father, mother and children – Leib, Abram and Aron (Arkady) – were in different camps. Many of the deportees died in the camps. Among them was the grandfather of Abramovich. Nachman Leibovich died in 1942 in the NKVD camp in the settlement of Resheti, Krasnoyarsk Territory.[14]

Having lost both parents before the age of 4,[15] Abramovich was raised by relatives and spent much of his youth in the Komi Republic in northern Russia. Abramovich is the Chairman of the Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia, and a trustee of the Moscow Jewish Museum.[18] Abramovich decided to establish a forest of some 25,000 new and rehabilitated trees, in memory of Lithuania's Jews who were murdered in the Holocaust, plus a virtual memorial and tribute to Lithuanian Jewry (Seed a Memory) enabling people from all over the world to commemorate their ancestors' personal stories by naming a tree and including their name in the memorial.[19]

Career edit

Business career edit

Abramovich entered the business world during his army service.[20] He first worked as a street-trader, and then as a mechanic at a local factory.[citation needed] Abramovich attended the Gubkin Institute of Oil and Gas in Moscow,[21] then traded commodities for the Swiss trading firm Runicom.[22]

In 1988, as perestroika created opportunities for privatization in the Soviet Union, Abramovich gained a chance to legitimise his old business.[23] He and his first wife, Olga, set up a company making dolls. Within a few years his wealth spread from oil conglomerates to pig farms.[24] He has traded in timber, sugar, food stuffs and other products.[25] In 1992, he was arrested and sent to prison in a case of theft of government property.[26]

Friendship with Boris Berezovsky edit

According to two different sources, Abramovich first met Berezovsky either at a meeting with the Russian businessmen in 1993[27] or in the summer of 1995.[28]

Berezovsky and Abramovich registered an offshore company, Runicom Ltd., with five subsidiaries. Abramovich headed the Moscow affiliate of the Swiss firm, Runicom. In August 1995, Boris Yeltsin decreed the creation of Sibneft, of which Abramovich and Berezovsky were thought to be top executives.[26]

edit

In 1995, Abramovich and Berezovsky acquired a controlling interest in the large oil company Sibneft in a rigged auction.[29] The deal took place within the controversial loans-for-shares program and each partner paid US$100 million for half of the company, above the stake's stock market value of US$150 million at the time, and rapidly turned it up into billions. The fast-rising value of the company led many observers, in hindsight, to suggest that the real cost of the company should have been in the billions of dollars (it was worth US$2.7 billion at that time).[30][31][29] Abramovich later admitted in court that he paid billions of dollars of bribes to government officials and gangsters to acquire and protect his assets.[32] As of 2000, Sibneft annually produced US$3 billion worth of oil.[33]

The Times claimed that he was assisted by Badri Patarkatsishvili in the acquisition of Sibneft.[34][35][36][37] After Sibneft, Abramovich's next target was the aluminium industry. After privatisation, the "aluminium wars" led to murders of smelting plant managers, metals traders and journalists as groups battled for control of the industry. Abramovich was initially hesitant to enter into the aluminium business, claiming that "every three days someone was murdered in that business".[38] Abramovich sold Sibneft to the Russian government for $13 billion in 2005.[29]

Relationship with Boris Berezovsky and Badri Patarkatsishvili edit

In 2011, Abramovich's longtime business partner filed a civil suit, Berezovsky v Abramovich,[39] in the High Court of Justice in London. He accused Abramovich of blackmail, breach of trust and breach of contract. The suit sought over £3 billion in damages.[40]

On 31 August 2012, the High Court dismissed the lawsuit. The High Court judge stated that because of the nature of the evidence, the case hinged on whether to believe Berezovsky or Abramovich's evidence. The judge found Berezovsky to be "an unimpressive, and inherently unreliable witness, who regarded truth as a transitory, flexible concept, which could be moulded to suit his current purposes", whereas Abramovich was seen as "a truthful, and on the whole, reliable witness".[40][41]

Evidence in the case edit

In 2011, a transcript emerged of a taped conversation that took place between Abramovich and Berezovsky at Le Bourget airport in December 2000. Badri Patarkatsishvili, a close acquaintance of Berezovsky, was also present and secretly had the conversation recorded.[42][43] During the discussion, Berezovsky spoke of how they should "legalise" their aluminium business, and later claimed in court that he was an undisclosed shareholder in the aluminium assets and that "legalisation" in this case meant to make his ownership "official". In response, Abramovich states in the transcript that they cannot legalise because the other party in the 50–50 joint venture (Rusal) would need to do the same, in a supposed reference to his business partner Oleg Deripaska. Besides Deripaska, references are made to several other players in the aluminium industry at the time that would have had to "legalise" their stake. Abramovich's lawyers later claimed that "legalisation" meant structuring protection payments to Berezovsky to ensure they complied with Western antimoney-laundering regulations.[44][45]

The Times also observed:[34]

Mr Abramovich discloses that there was a showdown at St Moritz airport in Switzerland in 2001 when Mr [Badri] Patarkatsishvili asked him to pay US$1.3 billion (€925 million) to Mr Berezovsky. "The defendant agreed to pay this amount on the basis that it would be the final request for payment by Mr Berezovsky and that he and Mr Patarkatsishvili would cease to associate themselves publicly with him and his business interests." The payment was duly made.

Mr Abramovich was also willing to pay off Mr Patarkatsishvili. He states that he agreed to pay US$585 million (€416 million) "by way of final payment".

Mr Abramovich denies that he helped himself to Mr Berezovsky's interests in Sibneft and aluminium or that he threatened a friend of the exile. "It is denied that Mr Abramovich made or was party to the alleged explicit or implicit coercive threats or intimidation," he states.

According to court-papers submitted by Abramovich,[34] Abramovich mentions in the court-papers:

Prior to the August 1995 decree [of Sibneft's creation], the defendant [Abramovich] informed Mr Berezovsky that he wished to acquire a controlling interest in Sibneft on its creation. In return for the defendant [Abramovich] agreeing to provide Mr Berezovsky with funds he required in connection with the cash flow of [his TV company] ORT, Mr Berezovsky agreed he would use his personal and political influence to support the project and assist in the passage of the necessary legislative steps leading to the creation of Sibneft. Mr Patarkatsishvili did ... provide assistance to the defendant in the defendant's acquisition of assets in the Russian aluminium industry.

Investments in technology edit

In 2015, Abramovich invested and led a $30 million round of funding with businessman OD Kobo Chairman of PIR Equities.[46][47] Other partners include several well-known people from the music industry, among them David Guetta, Nicki Minaj, Tiësto, Avicii, will.i.am, Benny Andersson, Dave Holmes and others.[48]

Also StoreDot, founded by Doron Myersdorf, where Abramovich has invested over $30 million.[49]

Football edit

Chelsea Football Club edit

In June 2003, Abramovich became the owner of the companies that control Chelsea in West London.[50] The previous owner of the club was Ken Bates, who later bought rivals Leeds United. Chelsea immediately embarked on an ambitious programme of commercial development, with the aim of making it a worldwide brand at par with footballing dynasties such as Manchester United and Real Madrid, and also announced plans to build a new state-of-the-art training complex in Cobham, Surrey.[51]

Since the takeover, the club has won 18 major trophies – the UEFA Champions League twice, the UEFA Europa League twice, the UEFA Supercup twice, the Premier League five times, the FA Cup five times (with 2010 providing the club's first ever league and FA Cup double) and the League Cup three times, making Chelsea the most successful English trophy winning team during Abramovich's ownership, equal with Manchester United (who have also won 16 major trophies in the same time span). His tenure has also been marked by rapid turnover in managers. Detractors have used the term "Chelski" to refer to the new Chelsea under Abramovich, to highlight the modern phenomena of billionaires buying football clubs and "purchasing trophies", by using their personal wealth to snap up marquee players at will and distorting the transfer market, citing the acquisition of Andriy Shevchenko for a then-British record transfer fee of around £30 million (€35.3 million).[52]

In the year ending June 2005, Chelsea posted record losses of £140 million (€165 million) and the club was not expected to record a trading profit before 2010, although this decreased to reported losses of £80.2 million (€94.3 million) in the year ending June 2006.[53] In a December 2006 interview, Abramovich stated that he expected Chelsea's transfer spending to fall in the years to come.[54] UEFA responded to the precarious profit/loss landscape of clubs, some owned by billionaires, but others simply financial juggernauts like Real Madrid, with Financial Fair Play regulations.

Chelsea finished their first season after the takeover in second place in the Premier League, up from fourth the previous year. They also reached the semi-finals of the Champions League, which was eventually won by the surprise contender Porto, managed by José Mourinho. For Abramovich's second season at Stamford Bridge, Mourinho was recruited as the new manager, replacing the incumbent Claudio Ranieri. Chelsea ended the 2004–05 season as league champions for the first time in 50 years and only the second time in their history. Also high were Abramovich's spending regarding purchases of Portuguese football players. According to record newspaper accounts, he spent 165.1 million euros in Portugal: 90.9 with Benfica players and 74.2 with Porto players.[55]

During his stewardship of the club, Abramovich was present at nearly every Chelsea game and showed visible emotion during matches, a sign taken by supporters to indicate a genuine love for the sport, and often visited the players in the dressing room following each match. This stopped for a time in early 2007, when press reports appeared of a feud between Abramovich and manager Mourinho regarding the performance of certain players such as Andriy Shevchenko.[56] On 1 July 2013, Chelsea celebrated ten years under Abramovich's ownership. Before the first game of the 2013–14 season against Hull City on 18 August 2013, Abramovich thanked Chelsea supporters for ten years of support in a short message on the front cover of the match programme, saying: "We have had a great decade together and the club could not have achieved it all without you. Thanks for your support and here's to many more years of success."

In March 2017, Chelsea announced it had received approval for a revamped £500m stadium at Stamford Bridge with a capacity of up to 60,000.[57] On 15 July 2018, the renewal of Abramovich's British visa by the Home Office, and his subsequent withdrawal of the application, in May 2018 Chelsea halted plans to build a £500m stadium in south-west London due to the "unfavourable investment climate" and the lack of assurances about Abramovich's immigration status. Abramovich was set to invest hundreds of millions of pounds for the construction of the stadium.[58][59] Abramovich has been accused of purchasing Chelsea at the behest of Vladimir Putin, but he has denied the claim.[60][61][62] Putin's People, a book by journalist Catherine Belton, a former Financial Times Moscow correspondent, formerly made such an assertion, but after libel action by Abramovich against Belton and the book's British publisher HarperCollins, the claims were agreed in December 2021 to be stated as having no factual basis in future editions.[63]

In 2021, Abramovich was criticized for trying to enter Chelsea into the newly announced European Super League. The competition was widely scrutinized for encouraging greediness among the richer, larger football clubs, which would have undermined the significance of existing football competitions;[citation needed][64] however, just two days later, Abramovich pulled the club out of the new competition, with other English clubs following suit, causing the league to suspend operations. In 2022, it was reported that Abramovich was owed $2 billion from Chelsea. According to Forbes, Abramovich's loan was insurance in case the British government considered sanctioning him due to his close relationship with the Putin regime in Russia.[65] On 26 February 2022, during the Russo-Ukrainian War, Abramovich handed over "stewardship and care" of the club to the Chelsea Charitable Foundation.[66]

Abramovich released an official statement on 2 March 2022 confirming that he was selling the club due to the ongoing situation in Ukraine.[67] Although the UK government froze Abramovich's assets in the United Kingdom on 10 March[68] due to his "close ties with [the] Kremlin", it was made clear that the Chelsea club would be allowed to operate in activities which were football related.[69] On 12 March, the Premier League disqualified Abramovich as a director of Chelsea.[70]

On 7 May 2022, Chelsea announced that a new ownership group led by Todd Boehly and Clearlake Capital had agreed on the terms to acquire the club.[71]

CSKA Moscow edit

In March 2004, Sibneft agreed to a three-year sponsorship deal worth €41.3 million (US$58 million) with the Russian team CSKA Moscow.[72] Although the company explained that the decision was made at management level, some viewed the deal as an attempt by Abramovich to counter accusations of being "unpatriotic" which were made at the time of the Chelsea purchase. UEFA rules prevent one person owning more than one team participating in UEFA competitions, so Abramovich has no equity interest in CSKA. A lawyer, Alexandre Garese, is one of his partners in CSKA.

Following an investigation, Abramovich was cleared by UEFA of having a conflict of interest.[73] Nevertheless, he was named "most influential person in Russian football" in the Russian magazine Pro Sport at the end of June 2004. In May 2005, CSKA won the UEFA Cup, becoming the first Russian club ever to win a major European football competition. In October 2005, however, Abramovich sold his interest in Sibneft and the company's new owner Gazprom, which sponsors Zenit Saint Petersburg, cancelled the sponsorship deal.[74]

Russian national team edit

Abramovich also played a large role in bringing Guus Hiddink to Russia to coach the Russia national football team.[75] Piet de Visser, a former head scout of Hiddink's club PSV Eindhoven and now a personal assistant to Abramovich at Chelsea, recommended Hiddink to the Chelsea owner.[76]

National Academy of Football edit

In addition to his involvement in professional football, Abramovich sponsors a foundation in Russia called the National Academy of Football. The organization sponsors youth sports programs throughout the country and has constructed more than fifty football pitches in various cities and towns. It also funds training programs for coaches, prints instruction materials, renovates sports facilities and takes top coaches and students on trips to visit professional football clubs in England, the Netherlands and Spain. In 2006 the Academy of Football took over the administration of the Konoplyov football academy at Primorsky, near Togliatti, Samara Oblast, where over 1,000 youths are in residence, following the death at 38 of its founder, Yuri Konoplev.[77]

Political career edit

"Everyone's got their own reason. Some believe it's because I spent some of my childhood in the far north that I helped Chukotka, some believe it's because I had a difficult childhood that I helped Chukotka, some believe it's because I stole money that I helped Chukotka. None of these is real. When you come out and you see a situation and there are 50,000 people, you want to do something. I haven't seen anything worse than what I saw there in my life."

–Abramovich, on his political and charitable effort in Chukotka.[78]

In 1999, Abramovich was elected to the State Duma as the representative for the Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, an impoverished region in the Russian Far East. He started the charity Pole of Hope to help the people of Chukotka, especially children, and in December 2000, was elected governor of Chukotka, replacing Aleksandr Nazarov.

Abramovich was the governor of Chukotka from 2000 to 2008. It is believed that he invested over US$1.3 billion (€925 million) in the region.[79] Abramovich was awarded the Order of Honour for his "huge contribution to the economic development of the autonomous district [of Chukotka]", by a decree signed by the President of Russia.[80]

In early July 2008, it was announced that President Dmitry Medvedev had accepted Abramovich's request to resign as governor of Chukotka, although his various charitable activities in the region would continue. In the period 2000–2006 the average salaries in Chukotka increased from about US$165 (€117/£100) per month in 2000 to US$826 (€588/£500) per month in 2006.[26][81]

Informal Ukraine diplomacy edit

This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (April 2022) |

The day after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, Abramovich was contacted by Ukrainian magnates and asked to function as informal envoy to Putin.[82]

Abramovich played a key role in the release of Aiden Aslin and other foreign prisoners of war from Russian captivity.[83]

Sanctions edit

Abramovich is one of many Russian oligarchs named in the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, CAATSA, signed into law by President Donald Trump in 2017.[84] He is one of the Navalny 35.[85]

Following the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, on 10 March 2022 Abramovich was sanctioned by the UK as part of a group of seven Russian oligarchs.[86][87] Abramovich had his UK assets frozen and a travel ban was put in place. The British government said the sanctions were in response to Abramovich's alleged ties to the Kremlin and said the companies Abramovich controls could be producing steel used in tanks deployed offensively by Russia in Ukraine.[88] Abramovich denies that he has close ties to Vladimir Putin and the Kremlin.[10]

Also on 10 March Canada imposed sanctions against Abramovich as a businessman helping President Vladimir Putin in his war against Ukraine.[89][90]

On 14 March, Australia and on 15 March, the European Union followed Britain's suit and also imposed sanctions on Abramovich.[89][91][92] On 16 March Abramovich was added to the Swiss blacklist.[93] On 5 April 2022 Abramovich came under New Zealand sanctions for close ties with Vladimir Putin.[89][94]

On 19 October, Volodymyr Zelenskyy signed two decrees imposing personal sanctions against 256 Russian businessmen. Among them was Abramovich, being the only person on the list, the restrictions against whom will only work after the exchange of all Ukrainian prisoners and bodies of those killed during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[95]

In late March 2022, it was reported that Abramovich was house-hunting in Dubai, where his private plane had also been spotted, owing to the city's sanction-free status.[96] In March 2022, The Wall Street Journal reported that the United States administration deferred sanctions on Abramovich at the urging of President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelensky, because of the oligarch's potential role in negotiations with Russia. The Russian government spokesperson Dmitry Peskov confirmed that Abramovich took part in the negotiations "at the initial stage". No further details of the nature of Abramovich's involvement in the process were disclosed by either party to the conflict.[97]

In December 2022, Canada announced that it would target him for the maiden use of its SEMA seizure and forfeiture mechanism.[98] The government alleged that US$26 million held by Granite Capital Holdings Ltd was in fact Abramovich's and stated that it "will now consider making a court application to forfeit the [Abramovich Assets] permanently to the Crown."[98]

Abramovich failed to overturn, in December 2023, the EU sanctions, when the Court of Justice of the European Union dismissed his lawsuit.[99]

Alleged poisoning edit

On March 3 and 4, 2022, Abramovich attended peace talks on the Ukraine–Belarus border. Abramovich, Ukrainian politician Rustem Umierov and one other negotiator suffered initial symptoms consistent with likely poisoning with an unknown chemical substance, involving "piercing pain in the eyes", inflammation of the eyes and skin with some skin peeling. They all recovered quickly. Bellingcat investigated the allegation and said that chocolate or water that the three had consumed may have been laced with poison; experts took samples of the substance but were unable to identify the type of material used owing to the passage of time. Western sources said the low dosage of poison was aimed to serve as a warning, most likely to Abramovich, and suspected the attack may have been carried out by hardliners in Moscow who tried to sabotage peace talks.[100][101][102][103] An unnamed US official said that the illness was caused by "environmental factors" rather than poisoning. Additionally, an official in the Ukrainian president's office, Igor Zhovkva, informed the BBC that while he hadn't spoken to Mr Abramovich, participants of the Ukrainian delegation were "fine" and one had said the story was "false".[103] Frank Gardiner of the BBC said the US denial may be caused by a reluctance to respond in a retaliatory manner to Russia by accepting the deployment of chemical weapons in Ukraine.[103] A spokesman for Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy said that he had no information about a suspected poisoning.[104]

Relationship with Russian leaders edit

Boris Yeltsin edit

By 1996, at the age of 30, Abramovich had become close to President Boris Yeltsin and had moved into an apartment inside the Kremlin at the invitation of the Yeltsin family.[105]

In 1999, the 33-year-old Abramovich was elected governor of the Russian province of Chukotka. He ran for a second term as governor in 2005. The Kremlin press service reported that Abramovich's name had been sent for approval as governor for another term to Chukotka's local parliament, which confirmed his appointment on 21 October 2005.

Vladimir Putin edit

Abramovich was the first person to recommend to Yeltsin that Vladimir Putin be his successor as the Russian president.[106]: 135 When Putin formed his first cabinet as Prime Minister in 1999, Abramovich interviewed each of the candidates for cabinet positions before they were approved.[31]: 102 Subsequently, Abramovich would remain one of Putin's closest confidants. In 2007, Putin consulted in meetings with Abramovich on the question of who should be his successor as president; Medvedev was personally recommended by Abramovich.[106]: 135, 271

Chris Hutchins, a biographer of Putin, described the relationship between the Russian president and Abramovich as like that between a father and a favourite son. In the early 2000s, Abramovich said that when he addressed Putin he uses the Russian language's formal "вы" (like Spanish "usted" or German "Sie"), as opposed to the informal "ты" (like Spanish "tú" or German "du") as a mark of respect for Putin's seniority.[107] Within the Kremlin, Abramovich was referred to as "Mr. A".[108]

In September 2012, the England and Wales High Court judge Elizabeth Gloster claimed that Abramovich's influence on Putin was limited: "There was no evidential basis supporting the contention that Mr. Abramovich was in a position to manipulate, or otherwise influence, President Putin, or officers in his administration, to exercise their powers in such a way as to enable Mr. Abramovich to achieve his own commercial goals."[109]

Gloster oversaw the case between Russian oligarchs Boris Berezovsky and Abramovich. She found Berezovsky to be "an inherently unreliable witness" and sided with Abramovich in 2012. It later emerged that Gloster's stepson had been paid almost £500,000 to represent Abramovich as a barrister early in the case. Her stepson's involvement was alleged to be more than had been disclosed. Berezovsky stated, "Sometimes I have the impression that Putin himself wrote this judgment". Gloster declined to comment.[110][111][112]

In 2021, it was reported by the Washington Examiner that the U.S. intelligence community believes Abramovich is a "bag carrier", or a financial middleman, for Putin.[113]

Controversies edit

Boris Berezovsky allegations edit

In 2011, Boris Berezovsky brought a civil case against Abramovich, called Berezovsky v Abramovich,[39] in the High Court of Justice in London, but Berzovsky was unsuccessful in the case.[40]

Bribery edit

In 2008, The Times reported that court papers showed Abramovich admitting that he paid billions of dollars for political favors and protection fees for shares of Russia's oil and aluminum assets.[114]

Allegations of loan fraud edit

An allegation emerging from a Swiss investigation links Roman Abramovich, through a former company, and numerous other Russian politicians, industrialists and bankers to using a US$4.8 billion (€3.4 billion) loan from the IMF as personal slush fund; an audit sponsored by the IMF itself determined that all of the IMF funds had been used appropriately.[115]

In January 2005, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) indicated that it would be suing Abramovich over a £9 million (US$14.9 million/€10.6 million) loan.[116] The EBRD said that it is owed US$17.5 million (€12.45 million/£10.6 million) by Runicom, a Switzerland-based oil trading business which had been controlled by Abramovich and Eugene Shvidler. Abramovich's spokesman indicated that the loan had previously been repaid.[117]

Antitrust law violation in Russia edit

Russia's antitrust body, the Federal Antimonopoly Service, claimed that Evraz Holding, owned in part by Abramovich, had breached Russian competition law by offering unfavorable terms for contractors and discriminating against domestic consumers for coking coal, a key material used in steel production.[118]

Dispute with Kolomoyskyi edit

According to Putin, Abramovich has been cheated by Ukrainian-Cypriot-Israeli oligarch Igor Kolomoyskyi. Putin claimed in 2014 that Kolomoyskyi had reneged on a contract with Abramovich, saying that the pair signed a multibillion-dollar deal on which Kolomoyskyi never delivered.[119]

Pollution and climate change edit

According to The Guardian, in 2015 his $766m stake in Evraz, the steel and mining company, gave him ownership of about a quarter of Russia's largest coal mine, the Raspadskaya coal complex in Siberia, whose reserves represented 1.5GT of carbon emissions, comparable to the annual output of Russia itself.[120]

According to The Conversation, "Roman Abramovich, who made most of his $19 billion fortune trading oil and gas, was the biggest polluter on our list" of most polluting billionaires, estimating "that he was responsible for at least 33,859 metric tons of CO2 emissions in 2018 – more than two-thirds from his yacht."[121]

Funding of Israeli settlements edit

An investigation by BBC News Arabic has found that Abramovich controls companies that have donated $100 million to an Israeli settler organisation, Elad, which aims to strengthen the Jewish connection to the annexed East Jerusalem, and renew the Jewish community in the City of David. Analysis of bank documents indicate Abramovich is the largest single donor to the organization. The bank documents - known as the FinCEN Files - were leaked to BuzzFeed News, then shared with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) and the BBC.[122][123][124][125]

Personal life edit

Abramovich is described by those close to him as naturally secretive, reserved, calculating, efficient, and devoid of feeling and values. He often dresses simply. He is described as shy and rarely makes eye contact. Le Monde claimed his personal character contrasts with that of other oligarchs.[126]

Marriages and children edit

Abramovich has been married and divorced three times. In December 1987, following a brief stint in the Soviet Army, he married Olga Yurevna Lysova;[26] they divorced in 1990. In October 1991, he married a former Russian Aeroflot stewardess, Irina Malandina.[127] They have five children; Ilya, Arina, Sofia, Arkadiy and Anna.[127][128] His eldest daughter Anna is a graduate of Columbia University and lives in New York City,[129] and his daughter Sofia is a professional equestrian who lives in London after graduating from Royal Holloway, University of London.[130]

On 15 October 2006, the News of the World reported that Irina had hired two top UK divorce lawyers, following reports of Abramovich's close relationship with the then 25-year-old Dasha Zhukova, daughter of a prominent Russian oligarch, Alexander Zhukov. The Abramoviches replied that neither had consulted attorneys at that point.[131][132] However, they later divorced in Russia in March 2007,[26] with a reported settlement of US$300 million (€213 million).[127][133] Abramovich married Zhukova in 2008, and they have two children, a son, Aaron Alexander, and a daughter, Leah Lou.[128] In August 2017, the couple announced that they would separate;[134] and their divorce was finalized in 2018.[135]

Citizenships and residency edit

Citizenship in Israel edit

In May 2018, Abramovich became an Israeli citizen a month after the UK delayed renewing his visa. Following the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal, British authorities delayed the renewal of his visa, as tensions rose between the UK and Russia.[136] Abramovich had been travelling in and out of the UK for years on a Tier-1 investor visa, designed for wealthy foreigners who invest at least £2 million in Britain. Abramovich, who is Russian-Jewish, exercised his birthright under Israel's Law of Return, which states that Jews from anywhere in the world can become citizens of Israel. As an Israeli, Abramovich can now visit Britain visa-free but is not permitted to work or conduct business transactions.[137][138]

Abramovich owns the Varsano boutique hotel in the Neve Tzedek neighborhood of Tel Aviv, Israel, which he bought for 100 million NIS in 2015 from Israeli actress and model Gal Gadot's husband Yaron "Jaron" Varsano and his brother Guy Varsano.[139] In January 2020, Abramovich purchased a property in Herzliya Pituah, Israel, for a record 226 million NIS.[140]

In 2015, Abramovich donated approximately $30m to Tel Aviv University to establish an innovative center for nanoscience and nanotechnology, which aspires to become one of the leading facilities in the Middle East. Among Abramovich's other beneficiaries is the Sheba Medical Center in Tel HaShomer, Israel, to which he has donated in excess of $60m for various advanced medicine ventures.[141] These include the establishment of a new nuclear medicine center spanning 2,000 sq.m., the Sheba Cancer and Cancer Research Centers, the Pediatric Middle East Congenital Heart Center and the Sheba Heart Center. A donation that Abramovich made to Keren Kayemet LeIsrael-Jewish National Fund (KKL-JNF) for a comprehensive forest rehabilitation program in Israel's southern Negev desert, helps to combat the area's rising desertification and promotes increasing nature tourism to the area. Alongside his philanthropic activity, Abramovich has invested some $120m in 20 Israeli start-ups ranging from medicine and renewable energy, to social media.[139]

Recently, due to the alarming increase in COVID-19 cases in Israel, Abramovich gave Sheba Hospital another donation for a new subterranean Intensive Care Unit, spanning 5,400 sq.m., to provide Israel with vital crisis response in times of national emergencies. Abramovich continuously contributes to Jewish art and culture initiatives, such as the M.ART contemporary culture festival in Tel Aviv, Israel.[12]

Controversy in Switzerland edit

Abramovich filed an application for a residence permit in the canton of Valais, Switzerland, in July 2016, a tax-friendly home to successful businessmen, and planned to transfer his tax residency to the Swiss municipality. Valais authorities readily agreed to the request and transferred the application to the Swiss State Secretariat for Migration for approval. Once there, FedPol investigators expressed suspicions and opposed the request. As a result, Abramovich withdrew his application in June 2017. After a three-year legal saga, in 2021 Swiss authorities cleared Abramovich of any suspicion.[142]

Controversy in Portugal edit

In April 2021, Abramovich became a Portuguese citizen as part of the country's Nationality Act; his genealogy was vetted by experts who look for "evidence of interest in Sephardic [Jewish] culture".[citation needed] Though Reuters noted that there is little known history of Sephardi Jews in Russia,[143] Abramovich had donated money to projects honouring the legacy of Portuguese Sephardi Jews in Hamburg, Germany.[144][143] However, on 11 March 2022, the leader of the Jewish Community in Porto, Rabbi Daniel Litvak, was arrested by Portuguese police at Porto airport amid allegations that certification of Sephardi Jewish origin had been issued corruptly in several cases.[145][146] The allegations were later dropped for lack of evidence, with the judges criticizing the behaviour of the prosecutors and of law enforcement, and saying all the allegations were "generalities".[147][148]

Wealth edit

According to Forbes, as of March 2016, Abramovich had a net worth of US$7.6 billion, ranking him as the 155th richest person in the world.[149] Prior to the 2008 financial crisis, he was considered to be the second richest person living within the United Kingdom.[150] Early in 2009, The Times estimated that due to the global economic crisis he had lost £3 billion from his £11.7 billion wealth.[151] In the summer of 2020, Abramovich sold the gold miner Highland Gold to Vladislav Sviblov.[152][153] On 5 March 2021, Forbes listed his net worth at US$14.5 billion, ranking him 113 on the Billionaires 2020 Forbes list.[154]

Wealth rankings edit

| Year | The Sunday Times Rich List |

Forbes The World's Billionaires | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Net worth (£) | Rank | Net worth (US$) | |

| 2010[155] | 2 | £7.40 billion |

50 |

$12 billion |

| 2011[156][155] | 3 | £10.30 billion | 53 | $13.4 billion |

| 2012[157][158] | 3 | £9.50 billion | 68 | $12.1 billion |

| 2013[159][160] | 5 | £9.30 billion | 107 | $10.3 billion |

| 2014[161] | 9 | £8.42 billion | 137 | $9.10 billion |

| 2015[162][163] | 10 | £7.29 billion | 137 | $9.10 billion |

| 2016[164][149] | 13 | £6.40 billion | 151 | $7.60 billion |

| 2017[165][166] | 13 | £8.053 billion | 139 | $11.50 billion |

| 2018[167][168] | 13 | £9.333 billion | 140 | $11.70 billion |

| 2019[169][170] | 9 | £11.221 billion | 107 | $12.40 billion |

| 2020[171][172] | 12 | £10.156 billion | 113 | $11.30 billion |

| 2021[173][154] | 8 | £12.101 billion | 142 | $14.50 billion |

| Legend | |

|---|---|

| Icon | Description |

| Has not changed from the previous year | |

| Has increased from the previous year | |

| Has decreased from the previous year | |

Charitable donations edit

Abramovich has reportedly donated more money to charity than any other living Russian.[174] Between 2009 and 2013, Abramovich donated more than US$2.5 billion to build schools, hospitals and infrastructure in Chukotka. Abramovich has reportedly spent approximately £1.5 bn on the Pole of Hope, his charity set up to help those in the Arctic region of Chukotka, where he was governor.[175] In addition, Evraz Plc (EVR), the steelmaker partly owned by Abramovich, donated US$164 million for social projects between 2010 through 2012, an amount that is excluded in Abramovich's US$310 million donations during this period.[174]

Abramovich was recognized by the Forum for Jewish Culture and Religion for his contribution of more than $500 million to Jewish causes in Russia, the US, Britain, Portugal, Lithuania, Israel and elsewhere over the past 20 years.[12] In June 2019, Abramovich donated $5 million to the Jewish Agency for Israel, to support efforts to combat anti-Semitism globally.[176]

Abramovich decided to establish a forest of some 25,000 trees, in memory of Lithuania's Jews who perished in the Holocaust, plus a virtual memorial and tribute to Lithuanian Jewry.[12] He also gave a substantial donation for the rehabilitation of the Jewish cemetery of Altona, now a neighborhood in the city of Hamburg. The project is carried out by B'nai B'rith International Portugal in partnership with Hamburg's Chabad.[177] Abramovich donates money to the Chabad movement[178] and, along with Michael Kadoorie and Jacob Safra, is one of the main benefactors of the Portuguese Jewish community and of B'nai B'rith International Portugal.[179]

Abramovich funds an extended programme in Israel that brings Jewish and Arab children together in football coaching sessions. More than 1,000 Arab and Jewish children each year will be brought together through football, with Chelsea funding the expanded set-up and club staff training local coaches. The expanded Playing Fair, Leading Peace programme will break down barriers and combat discrimination by mixing communities in Israel.[180] In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Abramovich paid for NHS staff to stay at the Stamford Bridge Millennium Hotel.[181]

Opposition to anti-semitism and hatred edit

During Abramovich's ownership of the club, Chelsea agreed to a three-year partnership with the Anti-Defamation League to expand their Center on Extremism.[182] Abramovich faced antisemitic messages during the 2021 Israel–Palestine crisis.[183]

Kick It Out chief executive Tony Burnett hailed Chelsea's stance on fighting anti-Semitism, pledging the anti-discrimination organisation will now look to follow the lead of the club. "Historically it's been alleged that Kick It Out was formed to fight racism against black players and coaches. We looked at our strategy and realised we weren't doing enough on anti-Semitism and we brought together a group of stakeholders with vast experience in this area."[184]

The Chelsea Foundation has launched a new program in partnership with the Peres Center for Peace and Innovation and the Israeli Football Association, introducing football sessions for Arab and Jewish children across Israel, a partnership that was developed following Chelsea Women's visit to Israel in 2019, during which the team took part in football and education workshops with Arab and Jewish girls, benefiting 1,000 children in the first year alone.[12][185]

Properties edit

In 2009, he bought 16 Kensington Palace Gardens in London, a 15-bedroom mansion, for £90 million.[186]

For $74 million, Abramovich purchased four Upper East Side townhouses in Manhattan in New York City: 9, 11, 13 and 15 East 75th Street.[187] These townhouses are planned to be combined into a megamansion that will measure 19,400 square feet and it is estimated that renovation costs will be an additional $100 million.[187]

Yachts edit

Abramovich has become the world's greatest spender on luxury yachts, and always maintains a fleet of yachts which the media have called "Abramovich's Navy":[188]

- Current boats

- Eclipse 162.5 m (533 ft) – Built in Germany by Blohm + Voss, she was launched in September 2009.[189] Abramovich was due to take delivery of the yacht in December 2009,[190] but was delayed for almost a year after extensive sea trials. The yacht's interior and exterior were designed by Terence Disdale. Eclipse is believed to have cost Abramovich around US$400 million and was the world's largest privately owned yacht until it was eclipsed in 2013 by the 180 m (590 ft) Azzam. The specification includes at least two swimming pools, a cinema, two helicopter landing-pads, several on-board tenders and a submarine that can be launched and dive to a depth of 160 ft. She is also equipped with armour plating surrounding the bridge and Abramovich's master suite, as well as bullet proof windows.[191]

- Solaris[192]

- A 2022 Financial Times report linked Abramovich to the 67-meter yacht Garçon, which is moored in Antigua.[193]

- Former boats

- Pelorus 115 m (377 ft) – Built by Lurssen for Sheikh Abdul Mohsen Abdulmalik Al-Sheikh in 2003, original owner of M/Y Coral Island and M/Y Sussurro, who received six offers to sell her before she was even completed. The Sheikh accepted the highest bid which was Abramovich. The interior was designed by Terence Disdale. The exterior was designed by Tim Heywood. Pelorus was refitted by Blohm + Voss in 2005 adding a new forward helipad and zero speed stabilizers. Given to Irina in 2009 as part of the divorce settlement; she was approached on David Geffen's behalf by broker Merle Wood, with Geffen paying US$300 million to take ownership in 2011.[194]

- Sussurro 49.5 m (162 ft) – Built by Feadship in 1998 for Sheikh Abdul Mohsen Abdulmalik Al-Sheikh.

- Ecstasea 85 m (279 ft) – Largest Feadship built at launch in 2004 for Abramovich. She has a gas turbine alongside the conventional diesels which gives her high cruising speed. Abramovich sold the boat to the Al Nayhan family in 2009.[195]

- Le Grand Bleu 112 m (367 ft) – Formerly owned by John McCaw; Abramovich bought the expedition yacht in 2003 and had her completely refitted by Blohm + Voss, including a 16 ft (4.9 m) swim platform and sports dock. He presented her as a gift to his associate and friend Eugene Shvidler in June 2006.

- Luna 115 m (377 ft) – Built by Lloyd Werft and delivered to Roman Abramovich in 2009 as an upgraded replacement for his Le Grand Bleu expedition yacht.[196] Sold to close friend, Azerbaijani-born billionaire Farkhad Akhmedov, in April 2014 for US$360m. Boasts a 1 million litre fuel tank, 7 engines outputting 15,000 hp propelling Luna to a maximum speed of 25 knots, 8 tenders, 15 cm ice-class steel hull and 10 VIP Cabins.

Aircraft edit

Abramovich owns a private Boeing 767-33A/ER, registered in Aruba as P4-MES. It is known as The Bandit[197] due to its livery. Originally the aircraft was ordered by Hawaiian Airlines but the order was cancelled and Abramovich bought it from Boeing. Abramovich had it refitted it to his own requirements by Andrew Winch, who designed the interior and exterior. The aircraft was estimated in 2016 to cost US$300 million and its interior is reported to include a 30-seat dining room, a boardroom, master bedrooms, luxury bathrooms with showers, and a spacious living room. The aircraft has the same air missile avoidance system as Air Force One.[197] In 2021 Abramovich exchanged the Boeing 767 for a Boeing 787-8 Dreamliner.[citation needed]

Other interests and activities edit

Art edit

Abramovich sponsored an exhibition of photographs of Uzbekistan by renowned Soviet photographer Max Penson (1893–1959) which opened on 29 November 2006 at the Gilbert Collection at Somerset House in London. He previously funded the exhibition "Quiet Resistance: Russian Pictorial Photography 1900s–1930s" at the same gallery in 2005.[198] Both exhibits were organized by the Moscow House of Photography.[199]

In May 2008, Abramovich emerged as a major buyer in the international art auction market. He purchased Francis Bacon's Triptych 1976 for €61.4 million (US$86.3 million) (a record price for a post-war work of art) and Lucian Freud's Benefits Supervisor Sleeping for €23.9 million (US$33.6 million) (a record price for a work by a living artist).[200]

His former wife Dasha Zhukova manages the Garage Center for Contemporary Culture – a gallery of contemporary art in Moscow that was initially housed in the historical Bakhmetevsky Bus Garage building by Konstantin Melnikov. The building, neglected for decades and partially taken apart by previous tenants, was restored in 2007–2008 and reopened to the public in September 2008. Speed and expense of restoration is credited to sponsorship by Abramovich.[201]

New Year's Eve celebrations edit

In 2011, Abramovich hired the Red Hot Chili Peppers to perform at his estate in Baie de Gouverneur in St. Barth.[202] The performance included a special appearance from Toots Hibbert.[202] He reportedly spent £5 million on 300 guests, including George Lucas, Martha Stewart, Marc Jacobs, and Jimmy Buffett.[202] In 2014, he hired English singer Robbie Williams to headline a New Year's dinner for Vladimir Putin's "inner circle". The party took place in Moscow and appears to have been the inspiration for Williams' song "Party Like a Russian".[203]

In popular culture edit

Abramovich is a central character in Peter Morgan's 2022 play Patriots, dramatising the life of Boris Berezovsky.[204][205]

See also edit

References edit

Citations edit

- ^ Smith, David (24 December 2006). "Roman Abramovich interview: Inside the hidden world of Roman's empire". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "Abramovich says he will sell Chelsea". BBC Sport. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich: Rabbi investigated over Portuguese citizenship". BBC News. 12 March 2022. Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ Curado, Paulo (18 December 2021). "Roman Abramovich é cidadão português desde Abril". PÚBLICO (in Portuguese). Retrieved 28 September 2022.

- ^ "Billionaires 2021". Forbes. 5 March 2021. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich". forbes.com. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich immigrates to Israel". Globes. 28 May 2018. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich & family". Forbes. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ Conn, David (21 March 2022). "From poor orphan to billionaire oligarch: how Abramovich made his money". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

The court judgment also noted that Abramovich had "good relations" with Vladimir Putin...

- ^ a b "Ukraine war: Roman Abramovich sanctioned by UK". BBC News. 10 March 2022. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Roman Abramovich: From orphan to sanctioned billionaire oligarch". BBC. 29 March 2022. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

His mother, Irina, died of blood poisoning when he was one year old and his father died two years later after an accident with a construction crane.

- ^ a b c d e "Everything you need to know about mega philanthropist Roman Abramovich". The Jerusalem Post. 12 September 2021. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich. Biography. Abramovich, Roman Arkadievich – biography Who is Abramovich and what does he do". ezoteriker.ru. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Roman Abramovich – biography of a wealthy man". vk-spy.ru. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Roman Abramovich: the orphan who came in from the cold". The Daily Telegraph. 31 October 2011. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 1 November 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ "Beneath the cold 'death mask' of Abramovich". The Straits Times. 14 December 2015. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ Dunst, Charles (21 June 2018). "Billionaire Roman Abramovich helps brings ill Israeli kids to the World Cup". Jewish Telegraphic Agency. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ^ "Еврейский музей и центр толерантности". www.jewish-museum.ru. Archived from the original on 10 March 2014. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Abramovich makes 'significant' donation to forest in memory of Lithuanian Jews". jewishnews.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich built multi-billion-dollar career during his army service". Pravda. Archived from the original on 21 August 2011. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ Asthana, Anushka. "Roman Abramovich". The Times. London. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ FRONTLINE/WORLD . Moscow – Rich in Russia . How to Make a Billion Dollars – Roman Abramovich. PBS. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ "The Biography of the Great Oil Tycoon Roman Abramovich". Archived from the original on 10 February 2011. Retrieved 10 February 2011.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). Leadership Biographies (12 February 2010). - ^ "Battle of the oligarchs... the amazing showdown between Roman". Evening Standard. 6 October 2007. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ Gardham, Duncan (31 August 2012). "Berezovsky v Abramovich: How Roman Abramovich made his fortune". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 26 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Vandysheva, Olga (3 July 2008). "Roman Abramovich is no longer Chukotka's governor". Komsomolskaya Pravda. spb.kp.ru. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ Strauss, Julius. Shy orphan who rose to join Russia's super-rich. The Daily Telegraph. 6 November 2003. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ "He Was the Penniless Orphan". Archived from the original on 20 December 2010. Retrieved 20 December 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). bmi Voyager (28 October 2008). Retrieved 3 December 2010. - ^ a b c "Roman Abramovich: New evidence highlights corrupt deals". BBC News. 14 March 2022. Retrieved 14 March 2022.

- ^ Bandeira, Luiz Alberto Moniz (2019). The World Disorder: US Hegemony, Proxy Wars, Terrorism and Humanitarian Catastrophes. Springer. ISBN 9783030032043.

- ^ a b Midgley, Dominic; Hutchins, Chris (3 May 2005). Abramovich: The Billionaire from Nowhere. Harper Collins Willow. ISBN 978-0-00-718984-7.

- ^ "Chelsea owner admits he paid out billions in bribes". The Independent. Ireland. 5 July 2008. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ Wolosky, Lee S. (March–April 2000). "Putin's Plutocrat Problem". Foreign Affairs. 79 (2): 21. doi:10.2307/20049638. JSTOR 20049638.

- ^ a b c Kennedy, Dominic. Roman Abramovich admits paying out billions on political favours. The Times. 5 July 2008. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ OAO Siberian Oil Company (Sibneft) – Company History. Fundinguniverse.com. Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ Russia, Economy, Putin, Oligarchs, Loans for Shares – JRL 9–30–05 Archived 6 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Cdi.org (29 September 2005). Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ Russia, Oil, Gazprom, Sibneft – JRL 9–29–05 Archived 6 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine. Cdi.org (29 September 2005). Retrieved 3 December 2010.

- ^ "Abramovich Says He Feared Russia's Murderous Aluminum Trade". Bloomberg.com. 3 November 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Berezovsky v Abramovich Action 2007 Folio 942" (PDF). www.judiciary.gov.uk. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "Court win 'vindicates' Abramovich". Press Association. 31 August 2012. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich Wins Court Battle Against Berezovsky". BBC. 31 August 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2012.

- ^ Gardham, Duncan (11 October 2011). "Roman Abramovich is a "gangster", court told". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Gardham, Duncan (31 August 2012). "Berezovsky v Abramovich trial: Timeline". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Chazan, Guy (31 October 2011). "Evidence in Oligarch Case Makes New Link". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Franchetti, Mark (23 October 2011). "Roman Abramovich firm linked to Russian gangsters". The Sunday Times. ISSN 0956-1382. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Abramovich leads $30m round in OD Kobo's music start-up. Globes.co.il. Retrieved 20 April 2015.

- ^ Music Messenger, the App That Nicki Minaj and David Guetta Invested In, Is Exploding -- Here's Why. billboard.com. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ^ "Abramovich leads $30 million investment round in Music Messenger app". Reuters. 21 April 2015. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ Neuman, Nadav (12 June 2014). "Roman Abramovich invests $10m in StoreDot". Globes. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich receives apology from HarperCollins over Putin claims". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "Chelsea to build new training complex". Worldsoccer.com. 27 September 2004. Archived from the original on 11 October 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2007.

- ^ Scott, Matt (28 November 2006). "Rummenigge hits out over Chelsea's massive spending". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 28 November 2006.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich Calm About Chelsea's Record Losses". MosNews. 30 January 2006. Archived from the original on 23 March 2006. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- ^ "We will cut spending — Abramovich". BBC. 24 December 2006. Retrieved 19 January 2007.

- ^ "Reinado 'louco' de Abramovich no Chelsea: Agora são 120 milhões por Lukaku". www.record.pt (in European Portuguese). Retrieved 5 August 2021.

- ^ Lowe, Sid (13 April 2007). "Instability at Chelsea could force me to leave, says Mourinho". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 13 April 2007.

- ^ "Chelsea's new £500m stadium gets green light from London mayor". The Guardian. Press Association. 6 March 2017. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ "Abramovich's Chelsea FC shelves plan for £500m football stadium". Financial Times. 31 May 2018. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ "Chelsea halts stadium plans in latest Abramovich uncertainty". USA TODAY. 31 May 2018. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ "Russian Billionaire Abramovich Sues Author Catherine Belton for Defamation". Moscow Times. 23 March 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ Ahmed, Murad (22 March 2021). "Roman Abramovich sues HarperCollins over Chelsea acquisition claims". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2021.

- ^ "Russia tycoon sues publisher and Reuters reporter over Putin book". Reuters. 23 March 2021. Retrieved 12 June 2021.

- ^ Harding, Luke (22 December 2021). "Roman Abramovich settles libel claim over Putin biography". The Guardian. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ^ "Man Utd, Liverpool, Chelsea, Arsenal, Man City, and Tottenham agree to join European Super League". Sky Sports. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Dawkins, David. "Roman Abramovich Has Sanction Insurance: A $2 Billion Loan To Chelsea FC". Forbes. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Abramovich hands 'stewardship and care of Chelsea' to charitable foundation". the Guardian. 26 February 2022. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Statement from Abramovich". Chelsea FC. 2 March 2022. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ "Abramovich and Deripaska among 7 oligarchs targeted in estimated £15 billion sanction hit". GOV.UK. Retrieved 29 August 2023.

- ^ "UK freezes assets of Abramovich, six other Russian oligarchs". www.aljazeera.com. Retrieved 11 March 2022.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich: Premier League disqualifies Chelsea owner as director of club". BBC Sport. 12 March 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "Club statement". Chelsea F.C. 7 May 2022.

- ^ "CSKA strike it rich with oil giant". CNN. 17 March 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ "Abramovich's Soccer Interests Cleared by Uefa". Archived from the original on 11 November 2006. Retrieved 30 August 2016., mosnews.com (2 September 2004). Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ^ Sibneft ends CSKA Moscow sponsorship deal – ESPN FC. ESPN.COM (28 November 2005). Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ Australia & PSV Coach Guus Hiddink Recommended To Russia Football Union By Chelsea Owner Roman Abramovich, Who Will Pay Wages. Worldcuplatest.com. Archived 10 September 2006 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dutch scout is Abramovich's secret link. The Daily Telegraph. 9 June 2005.

- ^ Wilson, Jonathan (2 January 2008). "Russia reaps rewards of visionary school". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ^ Smith, David (24 December 2006). "Inside the hidden world of Roman's empire". The Guardian. Moscow. Archived from the original on 11 July 2012.

- ^ Smale, Will (29 September 2005). "What Abramovich may do with his money". BBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ "Russia's Putin Awards Order of Honor to Abramovich". Archived from the original on 6 February 2006. Retrieved 30 August 2016.. MosNews.com (20 January 2006). Retrieved 19 October 2006.

- ^ Walker, Shaun (4 July 2008). "Abramovich quits job in Siberia to spend more time on Western front". The Independent. London. Retrieved 4 July 2008.

- ^ Grove, Max Colchester, Jared Malsin and Thomas (1 April 2022). "Roman Abramovich's Abrupt Transformation From Shunned Oligarch to Wartime Envoy". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Retrieved 1 April 2022.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Roman Abramovich 'played key part' in release of Aiden Aslin and prisoners of war in Russia". The Daily Telegraph. 22 September 2022.

- ^ "Report to Congress Pursuant to Section 241 of the Countering America's Adversaries Through Sanctions Act of 2017 Regarding Senior Foreign Political Figures and Oligarchs in the Russian Federation and Russian Parastatal Entities" (PDF). 29 January 2018.

- ^ Johnson Hess, Abigail (30 January 2021). "Russian anti-corruption group founded by Navalny calls for Biden to sanction Putin allies in letter". CNBC. Retrieved 26 February 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine war: Roman Abramovich sanctioned by UK". BBC News. 10 March 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Amy Woodyatt and Niamh Kennedy (10 March 2022). "UK sanctions Russian oligarch and Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich". CNN. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ Ward, Victoria (10 March 2022). "Roman Abramovich accused of 'destabilising Ukraine' by supplying steel for 'Russian tanks'". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 10 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "ABRAMOVICH Roman Arkadyevich - biography, dossier, assets | War and sanctions". sanctions.nazk.gov.ua. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Canada slaps sanctions on Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich".

- ^ "EU hits Roman Abramovich with sanctions in new action against Russia". the Guardian. 15 March 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "Australia joins the UK and US in sanctioning key Russian oligarchs".

- ^ swissinfo.ch/urs (16 March 2022). "Swiss extend blacklist over Russia's invasion of Ukraine". SWI swissinfo.ch. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "Chelsea FC owner Roman Abramovich included in latest round of NZ sanctions". NZ Herald. Retrieved 1 January 2023.

- ^ "УКАЗ ПРЕЗИДЕНТА УКРАЇНИ №727/2022".

- ^ Ben Bartenstein, Nicolas Parasie, and Archana Narayanan (25 March 2022). "Abramovich's Dubai House Hunt Shows Russian Diaspora Widening". Bloomberg.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Kremlin confirms Roman Abramovich's role in Ukraine-Russia negotiations". CNN. 26 March 2022. Retrieved 26 March 2022.

- ^ a b "Canada announces first use of seizure and forfeiture mechanism against sanctioned persons | McCarthy Tétrault". 20 December 2022.

- ^ "Russian billionaire Abramovich fails to overturn EU sanctions as top court rejects appeal". 20 December 2023.

- ^ Trofimov, Yaroslav; Colchester, Max (28 March 2022). "Roman Abramovich and Ukrainian Peace Negotiators Suffer Symptoms of Suspected Poisoning". The Wall Street Journal. ISSN 0099-9660. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ Rose, David (28 March 2022). "Roman Abramovich 'had symptoms of poisoning'". The Times. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "Ukraine war latest: Russia plans to curb entry from 'unfriendly' states - LavrovRussian oligarch Roman Abramovich suffered suspected poisoning, reports say". BBC News. 28 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ a b c "Abramovich suffered suspected poisoning at talks". BBC News. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- ^ "Abramovich, Ukrainian Peace Negotiators Suffer Poisoning Symptoms – WSJ". The Moscow Times. 28 March 2022.

- ^ Levy, Adrian; Scott-Clark, Cathy (8 May 2004). "He won, Russia lost". Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ a b Sakwa, Richard (2011). The Crisis of Russian Democracy: The Dual State, Factionalism and the Medvedev Succession. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Inside the hidden world of Roman's empire". The Guardian. United Kingdom. 24 December 2006.

- ^ Fricker, Martin (5 November 2011). "Roman Abramovich revealed: The dangerous world of Roman and Russia's oligarchs". The Daily Mirror. United Kingdom.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich 'could not pull strings' with Putin". BBC News. 19 September 2012.

- ^ Belton 2020, pp. 4, 505–506.

- ^ Leppard, David (22 September 2012). "Berezovsky cries foul over £3.5bn Abramovich trial judge". The Times. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich wins court battle against Berezovsky". BBC News. 31 August 2012. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ "Come to America to write about Roman Abramovich". Washington Examiner. 24 November 2021. Retrieved 1 December 2021.

- ^ The Times: "Roman Abramovich admits paying out billions on political favours" Archived 7 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine 5 July 2008.

- ^ Kennedy, Dominic. Chelsea boss linked to $4.8bn loan scandal. The Times. 16 August 2004. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Sweeney, John; Behar, Richard (16 January 2005). "Bank to sue Abramovich over '£9m debt'". BBC News. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Hope, Christopher (19 January 2005). "European bank sues Abramovich over £9.4m 'debt'". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ Santarris, Ben (10 September 2008). "Evraz Accused of Breaking Russian Antitrust Laws". The Oregonian. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- ^ "Press conference on the situation in Ukraine". Genius. 4 March 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2020.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich among 'dirty dozen' people with biggest stakes in coal". The Guardian. 15 June 2015.

- ^ "Private planes, mansions and superyachts: What gives billionaires like Musk and Abramovich such a massive carbon footprint". The Conversation. 16 February 2021. Retrieved 27 September 2021.

- ^ "Israeli settlers' Chelsea boss backer". BBC. 21 September 2020.

- ^ "Leaks show Chelsea owner Abramovich donated $100m to Israeli right-wing group". The Times of Israel. 21 September 2020.

- ^ "Chelsea owner Abramovich 'donated $100m' to Israeli settler group". Al Jazeera. 22 September 2020.

- ^ "Companies Linked to Roman Abramovich Donated $100 Million to E. Jerusalem Right-wing Group". Haaretz. 21 September 2020.

- ^ Minisini, Lucas; Tonet, Aureliano (13 September 2023). "Looking for Roman Abramovich, the human chameleon". Le Monde. Paris. Archived from the original on 13 September 2023.

- ^ a b c "Abbandonata dal marito, Galina Berezovskij si consola con 227 milioni di euro". Il Giornal (in Italian). 24 July 2011.

Irina Vyacheslavovna Malandina, ex-hostess dell'Aeroflot nonché madre dei suoi 5 figli,

- ^ a b Miami Newsday: "Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich celebrates birth of his seventh child, his second with model Daria Zhukova" Archived 16 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine 14 April 2013.

- ^ "School of General Studies Class Day Ceremony - Columbia University". Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "The Russian elite daughters of Putin's inner circle slam his invasion of Ukraine". Fortune. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Kennedy, Dominic; Stewart, Will (17 October 2006). "Abramovich is 'deeply hurt' by claims his wife wants a divorce". The Times. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Mikhailova, Anna (13 July 2008). "Meeting Dasha Zhukova, Roman Abramovich's girl". The Times. Archived from the original on 11 May 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Harding, Luke (16 March 2007). "Goodnight Irina: Abramovich settles for mere £155m". Vedomosti reported in The Guardian. London: Guardian News and Media Ltd. Retrieved 16 March 2007.

- ^ "Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich splits from wife". BBC News. 7 August 2017. Archived from the original on 7 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ^ Rhoads, Julie (13 May 2021). "Chelsea Soccer Has Gone Untouched Despite Owner Roman Abramovich's $300 Million and $92.3 Million Divorces". Sportscasting | Pure Sports. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Oliphant, Roland (20 May 2018). "Roman Abramovich's UK visa delayed after government orders review of wealthy Russians in Britain". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ^ Sanchez, Raf (29 May 2018). "Roman Abramovich becomes an Israeli citizen a month after his UK visa was delayed". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ Oliver Bullough (30 September 2018). "Forget the pledges to act – London is still a haven for dirty Russian money". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ a b "Roman Abramovich to take out Israeli citizenship – report". Globes. 24 May 2018. Retrieved 3 November 2018.

- ^ Mirovsky, Arik (1 June 2020). "Roman Abramovich buys Herzliya home for NIS 226m – exclusive". Globes. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- ^ Welch, Ben (5 March 2018). "Roman Abramovich gives over £14m to Israeli hospital for nuclear medicine research". The Jewish Chronicle.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich cleared of all suspicions in Switzerland". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ^ a b Khalip, Andrei (18 December 2021). "Chelsea owner Abramovich gets Portuguese citizenship". Reuters. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich gains EU citizenship via Portuguese passport". Guardian. 19 December 2021. Retrieved 19 December 2021.

- ^ "Rabino que fez de Abramovich português tem mais de 3 milhões depositados em bancos". CNN. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ "Rabino que certificou nacionalidade de Abramovich detido pela PJ". Público. 11 March 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2022.

- ^ Willem Marx, Inside Roman Abramovich’s Quest for Portuguese Citizenship—An All-Access Pass to the EU, May 16, 2023, Vanity Fair

- ^ Sam Jones and Beatriz Ramalho da Silva, Portugal to change law under which Roman Abramovich gained citizenship, 16 March 2022, The Guardian

- ^ a b "The World's Billionaires 2016". Forbes. 2016. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ "Sunday Times Rich List 2008". The Sunday Times. 2008.

- ^ Hartley, Joanna (18 January 2009). "Abramovich looks to Gulf for Chelsea buyer". Arabian Business.

- ^ "Новый хозяин золота Абрамовича: кто покупает 40% Highland Gold". Forbes.ru. 13 August 2020. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ "Ñòðóêòóðà Ñâèáëîâà àíîíñèðîâàëà ïðèíóäèòåëüíûé âûêóï äîëåé ìèíîðèòàðèåâ Highland Gold". Interfax.ru. 17 November 2020.

- ^ a b "Forbes World's Billionaire List: The Richet in 2021". Forbes. Archived from the original on 27 May 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ a b "The World's Billionaires 2011". Forbes. 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Lipman, Jennifer (9 May 2011). "Chelsea's Abramovich scores on Rich List". The Jewish Chronicle. United Kingdom. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Sawer, Patrick (24 April 2012). "Sunday Times Rich List 2012: Wealth of richest grows to record levels". The Telegraph. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Walker, Tim (21 March 2012). "Rupert Murdoch makes Roman Abramovich 'an offer' to buy his newspaper titles". The Telegraph. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ "The Sunday Times Rich List, 2013 (annotated)". Genius. Genius Media Group Inc. 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Hickman, Martin (4 March 2013). "2013 Forbes Billionaires list: Record number of new entries appear on rich list, but Carlos Slim and Bill Gates still top the charts". The Independent. United Kingdom. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ "'Rich List' counts more than 100 UK billionaires". BBC News. United Kingdom. 11 May 2014. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ "Here is the list of Britain's 25 richest people". The Independent. United Kingdom. Press Association. 26 April 2015. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Blankfeld, Keren (23 March 2015). "Rags To Richest 2015: Billionaires Despite the Odds". Forbes. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ Brinded, Lianna (24 April 2016). "These are the top 25 richest people in Britain". Business Insider. United Kingdom. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ "These are the 25 richest people in Britain". Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "The World's Billionaires". Forbes. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ "These are the 19 richest people in Britain". Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "The List 2018 Ranking". Forbes. Retrieved 23 October 2018.

- ^ "The Sunday Times Rich List 2019". Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ "Billionaires 2019". Forbes. Retrieved 11 January 2020.

- ^ "The Sunday Times Rich List 2020". Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "Forbes Billionaires 2020". Forbes. Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- ^ "The Sunday Times Rich List 2021". Archived from the original on 29 May 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2021.

- ^ a b Meter, Henry; Sazonov, Alex (24 April 2013). "Most Charitable Russian Abramovich Leads Billionaires". Bloomberg News.

- ^ Lock, Georgina (5 October 2005). "The charitable side of ... Roman Abramovich". Third Sector.co.uk. Retrieved 17 December 2015.

- ^ Gross, Elana Lyn. "Roman Abramovich's $5 Million Gift Is The Latest Donation From Billionaires Fighting Hate Crimes". Forbes. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ "Descendants of Jews who died centuries ago in Altona will rehabilitate the local cemetery". Mazal News (in Portuguese). 8 September 2021. Retrieved 8 September 2021.

- ^ Goldman, M. (2 June 2003). The Piratization of Russia: Russian Reform Goes Awry. Routledge. p. 132.

- ^ "Bnei Brith". Holocaust Museum of Oporto. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Reporter, Jewish News. "Chelsea owner Roman Abramovich to fund Israeli coexistence football project". jewishnews.timesofisrael.com. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ Cuccinello, Hayley C. "Billionaire Tracker: Actions The World's Wealthiest Are Taking In Response To The Coronavirus Pandemic". Forbes. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Chelsea FC joins Anti-Defamation League in partnership". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved 7 July 2021.

- ^ "Chelsea keep faith in anti-discrimination projects despite rise in abuse". The Independent. 20 July 2021. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Chelsea to continue anti-discrimination projects despite anti-Semitism rise". Sky Sports. Retrieved 21 July 2021.

- ^ "Antisemitism in European soccer on the rise". Anti-Defamation League. 8 June 2021. Retrieved 7 September 2021.

- ^ Stewart, Heather (1 March 2022). "Roman Abramovich hastily selling UK properties, MP claims". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 March 2022.

- ^ a b Yannello, Christina (19 March 2019). "Roman Abramovich $180M UES "Urban Castle" Construction has Begun". Broker Pulse. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ "Admiral Chelski wins sea supremacy". The Sunday Times. 17 January 2007.

- ^ Sorrel, Charlie (21 September 2009). "Russian Billionaire Installs Anti-Photo Shield on Giant Yacht". Wired. Retrieved 21 September 2009.

- ^ Pancevski, Bojan. Roman Abramovich zaps snappers with laser shield. The Times. 20 September 2009. Retrieved 23 April 2010.

- ^ Stenning, Paul (31 October 2010). Waste of Money: Overspending in Football. Pitch Publishing. ISBN 978-1905411931.

- ^ T, Neha; Sharma, on (4 August 2021). "Take a look at Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich's $610M megayacht Solaris – The monster is 460ft long, comprises 48 cabins across eight decks, and is secure as the Air Force One". Luxurylaunches. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

- ^ Massoudi, Arash; Smith, Robert; Terazono, Emiko (29 March 2022). "Antigua investigates yacht with possible Abramovich ties". Financial Times. Archived from the original on 10 December 2022. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- ^ Stern, Jared Paul (14 July 2011). "David Geffen's New $300 Million Yacht Gets Upstaged By A Russian Businessman's Boat In Mallorca". businessinsider.com. Archived from the original on 7 January 2012. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- ^ Ecstasea video and pictures Archived 5 November 2006 at the Wayback Machine. Kupoprodaja.com.

- ^ Motor Yacht Luna 115m Delivered to Roman Abramovich Archived 15 April 2010 at the Wayback Machine. Superyachts.com (12 April 2010). Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ a b "20 Private Jets And The Famous People That Own Them". WorldLifeStyle. 2016. Archived from the original on 3 January 2020. Retrieved 12 March 2017.

- ^ "Roman Abramovich funds London exhibition". Archived from the original on 11 February 2007. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link). The Art Newspaper. 27 November 2006. - ^ Roman Abramovich and Dasha Zhukova Art Collection. artmagazine.nicholaschistiakov.com

- ^ "Roman Abramovich brings home the $86.3m Bacon and the $33.6m Freud" Archived 25 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. The Art Newspaper (1 June 2008).

- ^ Osipovich, Alexander (16 September 2008). "Abramovich's girlfriend opens major Moscow art gallery". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2008.

- ^ a b c Willis, Amy (28 December 2011). "Roman Abramovich hires Red Hot Chili Peppers for exclusive £5m News Year's Eve party". The Telegraph. United Kingdom. Archived from the original on 11 January 2022. Retrieved 15 December 2016.

- ^ Tucker, Maxim (28 October 2016). "Email leak reveals Robbie entertained top Putin aide". The Sunday Times.

- ^ "The Crown's Peter Morgan Spotlights Russian Oligarchs In World Premiere Of New Play, Tom Hollander To Star". Deadline Hollywood. 5 May 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "The Crown's Peter Morgan to premiere play about Russian oligarchs". The Guardian. 6 May 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

Sources edit

- Belton, Catherine (23 June 2020). Putin's People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and Then Took on the West. New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux. ISBN 978-0374238711.

Further reading edit

- Midgley, Dominic; Hutchins, Chris (3 May 2005). Abramovich: The Billionaire from Nowhere. Harper Collins Willow. ISBN 978-0-00-718984-7.

- Hoffman, David (4 December 2003). The Oligarchs: Wealth and Power in the New Russia. Public Affairs. ISBN 978-1-58648-202-2.