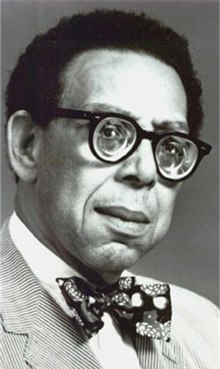

Robert Hayden (August 4, 1913 – February 25, 1980) was an American poet, essayist, and educator. He served as Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress from 1976 to 1978, a role today known as US Poet Laureate.[1] He was the first African American writer to hold the office.

Robert Hayden | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Asa Bundy Sheffey August 4, 1913 Detroit, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | February 25, 1980 (aged 66) Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S. |

| Occupation | Poet, essayist, and educator |

| Alma mater | Detroit City College (1936) University of Michigan (1944) |

| Notable works | Heart Shape in the Dust, A Ballad of Remembrance |

| Notable awards | Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress (U.S. Poet Laureate), 1976–78 |

| Spouse | Erma Inez Morris |

Biography edit

Robert Hayden was born Asa Bundy Sheffey in Detroit, Michigan, to Ruth and Asa Sheffey, who separated before his birth. He was taken in by a foster family next door, Sue Ellen Westerfield and William Hayden, and grew up in the Detroit neighborhood called "Paradise Valley".[2] The Haydens' perpetually contentious marriage, coupled with Ruth Sheffey's competition for her son's affections, made for a traumatic childhood. Witnessing fights and suffering beatings, Hayden lived in a house fraught with "chronic anger", the effects of which would stay with him throughout his life. On top of that, his severe visual problems prevented him from participating in activities such as sports in which nearly everyone else was involved. His childhood traumas resulted in debilitating bouts of depression that he later called "my dark nights of the soul".[3]

Because he was nearsighted and slight of stature, he was often ostracized by his peers. In response, Hayden read voraciously, developing both an ear and an eye for transformative qualities in literature. He attended Detroit City College (later called Wayne State University) with a major in Spanish and minor in English and left in 1936 during the Great Depression, one credit short of finishing his degree, to go to work for the Works Progress Administration Federal Writers' Project, where he researched black history and folk culture.[4]

Leaving the Federal Writers' Project in 1938, Hayden married Erma Morris in 1940 and published his first volume, Heart-Shape in the Dust (1940). He enrolled at the University of Michigan in 1941 and won a Hopwood Award there. Raised as a Baptist, he followed his wife into the Bahá'í Faith during the early 1940s,[4][5] and raised a daughter, Maia, in the religion. Hayden became one of the best-known Bahá'í poets. Erma Hayden was a pianist and composer and served as supervisor of music for Nashville public schools.[5]

In pursuit of a master's degree, Hayden studied under W. H. Auden, who directed his attention to issues of poetic form, technique, and artistic discipline. Auden's influence may be seen in the "technical pith of Hayden's verse".[2] After finishing his degree in 1942, then teaching several years at the University of Michigan, Hayden went to Fisk University in 1946, where he remained for 23 years, returning to the University of Michigan in 1969 to complete his teaching career (1969-80).[6][7] Concurrent with his teaching responsibilities at Fisk, he served as poet-in-residence at Indiana State University in 1967 and visiting poet at the University of Washington in 1969, the University of Connecticut in 1971, Dennison University in 1972, and Connecticut College in 1974.[8]

As a supporter of his religion's teaching of the unity of humanity, Hayden could never embrace Black separatism.[9] Thus, the title poem of Words in the Mourning Time ends in a stirring plea in the name of all humanity:

Reclaim now, now renew the vision of

a human world where godliness

is possible and man

is neither gook nigger honkey wop or kike

but manpermitted to be man.[5]

He died in Ann Arbor, Michigan, on February 25, 1980, aged 66.[10]

In 2012 the U.S. Postal Service issued a pane of stamps featuring ten great Twentieth Century American Poets, including Hayden.[11]

Career edit

By the 1960s and the rise of the Black Arts Movement, when a more youthful era of Afro-American artists composed politically and emotionally charged protest poetry overwhelmingly coordinated to a black audience, Hayden's philosophy about the function of poetry and the way he characterized himself as an author were settled. His refusal to revamp himself as indicated by the pictures of the 1960s earned him feedback from a few scholars and analysts. Hayden stayed consistent with his idea of poetry as an artistic frame instead of a polemical demonstration and to his conviction that poetry ought to, in addition to other things, address the qualities shared by mankind, including social injustice. Hayden's beliefs about the relationship of the artist to his poems likewise had an impact in his refusal to compose emotionally determined protest sonnets. Hayden's practice was to make separation between the speaker and the movement of the poem.[12]

His work often addressed the plight of African Americans, usually using his former home of Paradise Valley slum as a backdrop, as he does in the poem "Heart-Shape in the Dust". He made ready use of black vernacular and folk speech, and he wrote political poetry as well, including a sequence on the Vietnam War.

On the first poem of the sequence, he said: "I was trying to convey the idea that the horrors of the war became a kind of presence, and they were with you in the most personal and intimate activity, having your meals and so on. Everything was touched by the horror and the brutality and criminality of war. I feel that's one of the best of the poems."[13]

The impact of Euro-American innovation on Hayden's poetry and also his continuous assertions that he needed to be viewed as an "American poet" as opposed to a "black poet" prompted much feedback of him as an abstract "Uncle Tom" by Afro-American critics during the 1960s. However, Afro-American history, contemporary black figures, for example, Malcolm X, and Afro-American communities, especially Hayden's native Paradise Valley, were the subjects of a significant number of his poems.[10]

On April 7, 1966, Hayden's Ballad of Remembrance was awarded, by unanimous vote, the Grand Prize for Poetry at the first World Festival of Negro Arts in Dakar, Senegal.[4] The festival had more than ten thousand people from thirty-seven nations in attendance. However, on April 22, 1966, Hayden was denounced at a Fisk University conference of black writers by a group of young protest poets led by Melvin Tolson for refusing to identify himself as a black poet.[4]

Nature Poetry edit

Hayden is also known as a nature poet and is included in the anthology Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry. His poem "A Plague of Starlings" is one of the more famous of his nature-based poems.[14] The poem "Night-Blooming Cereus" is another example of Hayden's depiction of the natural world. The poem presents a series of haiku-like stanzas. Hayden said that he was inspired by a trip to Duluth, Minnesota during the smelt fishing season. He describes how the poem "[...]turned into a haiku, where you get it all by suggestion and implication".[15]

Poetic Influences edit

Robert Hayden has often been praised for his work crafting poems, the unique perspectives in his work, his exact language, and his absolute command of traditional poetic techniques and structures.[citation needed] Hayden's influences included Elinor Wylie, Countee Cullen, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Langston Hughes, Arna Bontemps, John Keats, W. H. Auden and W. B. Yeats.[citation needed]

As he became a well-known poet, he influenced society in a way that enforced the many ideas that were created during the 1900s. Some of his influential poems are, Angle of Ascent, Elegies for Paradise Valley, Night, Death, Mississippi, and Those Winter Sundays.[citation needed]

Legacy edit

Although Hayden was a very well-known poet in the present day, he was not as well-known back during his time as a poet. His poems were not highly regarded due to the vast discrimination and prejudice that was during the 1900s. However, in the modern day, his work is highly sought after as his poems big contributions to society.

Hayden was elected to the American Academy of Poets in 1975. His most famous poem is "Those Winter Sundays",[4][9] which deals with the memory of fatherly love and loneliness. It ranks among the most anthologized American poems of the twentieth century. He declined the position later called United States Poet Laureate previously, accepted the appointment for 1976–1977 during America's Bicentennial, and again in 1977–1978 though his health was failing then. He was awarded successive honorary degrees by Brown University (1976) and Fisk, (1978). In 1977 he was interviewed for television in Los Angeles on At One With by Keith Berwick.[13] In January 1980 Hayden was among those gathered to be honored by President Jimmy Carter and his wife at a White House reception celebrating American poetry.[16] He served for a decade as an editor of the Bahá'í journal World Order.[17]

Other famed poems include "The Whipping" (about a small boy being severely punished for some undetermined offense), "Middle Passage" (inspired by the events surrounding the United States v. The Amistad affair), "Runagate, Runagate", and "Frederick Douglass".[9]

Bibliography edit

- Heart-Shape in the Dust. Detroit, MI: Falcon Press 1940.

- The Lion and the Archer: Poems. With Myron O'Higgins. Nashville: Counterpoise, 1948.[18]

- A Ballad of Remembrance. London: Paul Breman, 1962.

- Selected Poems. NY: October House 1966.

- Words in the Mourning Time. NY: October House, 1970.

- The Night-Blooming Cereus. London: Paul Breman, 1972.

- Angle of Ascent: New and Selected Poems. NY: Liveright, 1975.

- American Journal. MA: Effendi Press, 1978.

- American Journal (expanded): NY: Liveright, 1982.

- Collected Prose: Robert Hayden. Ed. Frederick Glaysher. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan, 1984.

- Collected Poems: Robert Hayden. Ed. Frederick Glaysher. NY: Liveright, 1985.

Further reading edit

- Hatcher, John (1984). From the Auroral Darkness: The Life and Poetry of Robert Hayden (First ed.). Oxford: George Ronald. ISBN 0-85398-188-4.

- Related documents on Baháʼí Library Online.

- Williams, Pontheolla (1987). Robert Hayden: A Critical Analysis of His Poetry. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. pp. 241. ISBN 0-252-01289-5. Retrieved February 15, 2019.

- Goldstein, Laurence; Chrisman, Robert (2013). Robert Hayden: Essays on the Poetry. Ann Arbor,MI: University of Michigan Press. p. 350. ISBN 978-0-472-11233-3. Retrieved February 15, 2015.

- Bloom, Harold (2005). Robert Hayden: Bloom's Modern Critical Views. New York: Chelsea House. pp. 278. ISBN 0-791-08127-3.

References edit

- ^ "Poet Laureate Timeline: 1971-1980". Library of Congress. 2008. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- ^ a b Ramazani, Jahan; Ellmann, Richard; O'Clair, Robert (2003). The Norton Anthology of Modern and Contemporary Poetry. Vol. 2 (Third ed.). New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 0-393-97792-7.

- ^ "My Dark Nights of Soul - Poet Robert Hayden | Brown Foundation". brownvboard.org. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Buck, Christopher (2004). "Chapter 4: Robert Hayden". Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Vol. 2. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 177–181. ISBN 0-19-516725-2.

- ^ a b c Harriet Jackson Scarupa (January 1978). "Robert Hayden 'Poet Laureate'". Ebony. Vol. 33, no. 3. pp. 78–80, 82. ISSN 0012-9011. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Robert Hayden: African American Writer". www.myblackhistory.net. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ "Robert Hayden: American poet". Retrieved 3 Feb 2024.

- ^ Buck, Christopher (1 December 2006). "Hayden, Robert". The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Oxford African American Studies Center.

- ^ a b c Pontheolla T. Williams (1987). Robert Hayden: A Critical Analysis of His Poetry. University of Illinois Press. pp. 26–27, 66, 154, 162. ISBN 978-0-252-01289-1.

- ^ a b Poets, Academy of American. "About Robert Hayden | Academy of American Poets". poets.org. Retrieved August 4, 2019.

- ^ Beyondtheperf.com,

- ^ DeJong, Timothy (13 August 2013). Feeling With Imagination: Sympathy and Postwar American Poetry (Thesis).[page needed]

- ^ a b Goldstein, Laurence; Robert Chrisman, eds. (2001). Robert Hayden: Essays on the Poetry. University of Michigan Press. pp. 23, 106. ISBN 0-472-11233-3.

- ^ Dungy, Camille T., ed. (2009). Black Nature: Four Centuries of African American Nature Poetry. University of Georgia Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-8203-3431-8.

- ^ Laurence, Goldstein; Robert Chrisman, eds. (2001). Robert Hayden: Essays on the poetry. Michigan: University of Michigan Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 9780472112333.

- ^ "Carters host poets". Santa Cruz Sentinel. Santa Cruz, California. January 4, 1980. p. 22. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ "Poets, writers honor Robert Hayden". Baháʼí News. April 1990. pp. 8–9. Retrieved December 24, 2014.

- ^ Sorett, Josef (2016). Spirit in the Dark: A Religious History of Racial Aesthetics. Oxford University Press. pp. 120–121. ISBN 9780199844937.

External links edit

- Those Winter Sundays hermeneusis by ex-Poet Laureate Robert Pinsky

- Academy of American Poets listing

- About Hayden's Life And Career

- Online Selection of Poems

- Audio of Hayden's poem Soledad

- "On 'Middle Passage"":

- Poetry Foundation

- Modern American Poetry

- A Comprehension Review of Robert Hayden Essay

- Beagle, Donald (2018). The Hopwood Poets Revisited: Eighteen Major Award Winners. Library Partners Press. ISBN 978-1-61846-069-1., features an original essay about Robert Hayden by his fellow-poet and faculty colleague Laurence Goldstein, recalling the impact and aftermath of Hayden's Hopwood "Major Poetry" Award at the University of Michigan.

- "Hayden, Robert, 1913-1980". ProQuest Biographies. 2010. ProQuest 2137941089.

- ROBERT HAYDEN (1913–1980) from The New Anthology of American Poetry: Postmodernisms 1950-Present on JSTOR (stthomas.edu)

- Robert Hayden (1913-1980): An Appreciation on JSTOR (stthomas.edu)