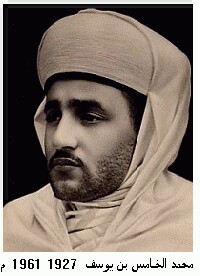

Mohammed al-Khamis bin Yusef bin Hassan al-Alawi (Arabic: محمد الخامس بن يوسف بن الحسن بن محمد بن عبد الرحمن بن هشام بن محمد بن عبد الله بن إسماعيل بن الشريف بن علي العلوي), better known simply Mohammed V (Arabic: محمد الخامس) (10 August 1909 – 26 February 1961), was the last Sultan of Morocco from 1927 to 1953 and from 1955 to 1957, and first King of Morocco from 1957 to 1961. A member of the 'Alawi dynasty, he played an instrumental role in securing the independence of Morocco from France and Spain.

| Mohammed V Mohammed bin Yusef محمد الخامس | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amir al-Mu'minin | |||||

| |||||

| King of Morocco | |||||

| Reign | 14 August 1957 – 26 February 1961 | ||||

| Successor | Hassan II | ||||

| Prime Ministers | |||||

| Sultan of Morocco | |||||

| Reign | 30 October 1955 – 14 August 1957 | ||||

| Predecessor | Mohammed bin 'Arafa | ||||

| Reign | 17 November 1927 – 20 August 1953 | ||||

| Predecessor | Yusef bin Hassan | ||||

| Successor | Mohammed bin 'Arafa | ||||

| Born | 10 August 1909 Fes, Morocco | ||||

| Died | 26 February 1961 (aged 51) Rabat, Morocco | ||||

| Burial | |||||

| Spouse | |||||

| Issue | |||||

| |||||

| Dynasty | Alawi | ||||

| Father | Yusef bin Hassan | ||||

| Mother | Lalla Yacout | ||||

| Religion | Sunni Islam | ||||

Mohammed was enthroned as sultan upon the death of his father Yusef bin Hassan in 1927. Early in his reign, his approval of the Berber Dahir drew widespread backlash and spurred an upsurge of Moroccan nationalism and opposition to continued French rule. Initially more amenable to colonial authorities, Mohammed grew increasingly supportive of the nationalist movement later on. During World War II he supported the Allies, participated in the 1943 Anfa Conference and took steps to protect Moroccan Jews from Vichy persecution.

Mohammed became a central figure of the independence cause after the war. In 1947, he delivered a historic speech in Tangier, in which he made an open appeal for Moroccan independence and emphasized the country's ties with the rest of the Arab world. His relationship with the French became increasingly strained afterwards as colonial rule grew more repressive. In 1953, French authorities deposed Mohammed, exiled him to Corsica (later transferring him to Madagascar) and installed his first cousin once removed Mohammed Ben Aarafa as sultan. The deposition sparked active opposition to the French protectorate and two years later, faced with rising violence in Morocco, the French government allowed Mohammed's return. In 1956, he successfully negotiated with France and Spain for Moroccan independence, and in the following year he assumed the title of king. Mohammed died in 1961 at the age of 51 and was succeeded by his eldest son, who took the throne as Hassan II.

Biography edit

Early life (1909–1927) edit

Sidi Mohammed bin Yusef was born on 10 August 1909 in Fes, and was his father's third son.[1][2] In March 1912, the Treaty of Fes was signed, turning Morocco into a French protectorate after a French invasion from the west and the east, resulting in an eventual capture of the capital, Fes. While Mohammed's father Yusef bin Hassan spent most of his time in the new capital, Rabat, Mohammed spent most of his time in the Royal Palace in Fes, where he received education in the traditional Moroccan way, Arabic religious lessons. However, Mohammed also learned the French language, which he did not master, as it was necessary to communicate with French authorities.[3]

Beginning of his reign (1927–1939) edit

Mohammed V was one of the sons of Sultan Yusef, who was enthroned by the French in September 1912 and his wife Yaqut.[5] On 18 November 1927, a "young and timid" 17-year-old Muhammad bin Yusef was enthroned after the death of his father and the departure of Hubert Lyautey.[6]

He married Hanila bint Mamoun in 1925 and in 1928, he married Abla bint Tahar, the latter gave birth to Hassan II in 1929. Finally he married Bahia bint Antar.

During World War II (1939–1945) edit

At the time of Mohammed's enthronement, the French colonial authorities were "pushing for a more assertive 'native policy.'"[6] On 16 May 1930, Sultan Muhammad V signed the Berber Dahir, which changed the legal system in parts of Morocco where Berber languages were primarily spoken (Bled es-Siba), while the legal system in the rest of the country (Bled al-Makhzen) remained the way it had been before the French invasion.[6][7] Although the sultan was under no duress, he was only 20 years old.[6] This dhahir "electrified the nation"; it was sharply criticized by Moroccan nationalists and catalyzed the Moroccan Nationalist Movement.[6]

Sultan Muhammad V participated in the Anfa Conference hosted in Casablanca during World War II.[6] On 22 January 1943, he met privately with the US president Franklin Delano Roosevelt and the Prime Minister of the UK Winston Churchill.[6] At this dinner, Roosevelt assured the sultan that "the post-war scene and the pre-war scene would ... sharply differ, especially as they related to the colonial question."[6] The sultan's 14-year-old son and future king of Morocco, Hassan II, also attended and later stated that Roosevelt said, "Ten years from now your country will be independent."[6]

"There are competing accounts of exactly what Mohammed V did or did not do for the Moroccan Jewish community" during the Holocaust.[8] However, "though a subject of debate, most scholars stress the benevolence of Mohammed V toward the Jews" during the Vichy era.[9] Mohammed reportedly refused to sign off on efforts by Vichy officials to impose anti-Jewish legislation upon Morocco and deport the country's 250,000 Jews to their deaths in Nazi concentration camps and extermination camps in Europe.[10] The sultan's stand was "based as much on the insult the Vichy diktats posed to his claim of sovereignty over all his subjects, including the Jews, as on his humanitarian instincts."[10] Partial Nazi race measures were enacted in Morocco over Mohammed's objection,[10] and Mohammed did sign, under the instructions of Vichy officials, two decrees that barred Jews from certain schools and positions.[11]

Nevertheless, Mohammed is highly esteemed by Moroccan Jews who credit him for protecting their community from the Nazi and Vichy French government,[8] and Mohammed V has been honored by Jewish organizations for his role in protecting his Jewish subjects during the Holocaust.[12] Some historians maintain that Mohammed's anti-Nazi role has been exaggerated; historian Michel Abitol writes that while Mohammed V was compelled by Vichy officials to sign the anti-Jewish dahirs, "he was more passive than Moncef Bay (ruler of Tunisia during the Second World War) in that he did not take any side and did not engage in any public act that could be interpreted as a rejection of Vichy's policy."[11]

Struggle for independence (1945–1953) edit

Sultan Muhammad V was a central figure in the independence movement in Morocco, or as it is also called: the Revolution of the King and the People (ثورة الملك والشعب). This Moroccan Nationalist Movement grew from protests regarding the Berber Dahir of 16 May 1930. He was critical of early movements for reform in French colonial administration in Morocco before becoming a supporter of independence later on.[13]

His central position in the Proclamation of Independence of Morocco further boosted his image as a national symbol. On 9 and 10 April 1947, he delivered two momentous speeches respectively at the Mendoubia and Grand Mosque of Tangier, together known as the Tangier Speech, appealing for the independence of Morocco without calling out specific colonial powers.[14][15]

In 1947, the rapid progress of the nationalist movement prompted Sidi Mohammed to demand independence for the first time during the Tangier speech, where he also called for the union of the Arabs and Morocco's membership of the Arab League which was founded in 1945, in which he praised, emphasized the close ties between Morocco and the rest of the Arab world. This rapprochement between the monarchy and the nationalist movement, whose projects differ, can be explained, according to historian Bernard Cubertafond, by the fact that "each side needs the other: the national movement sees the growing popularity of the king and his prudent but gradual emancipation from a protector who, in fact, left the treaty of 1912 to come to direct administration; the king cannot, except to discredit himself, cut himself off from a nationalist movement bringing together the living forces of his country and the elite of his youth, and he needs this power of protest to impose changes on France”.[16]

From then on, relations became strained with the French authorities, in particular with the new Resident General, General Alphonse Juin, who applied severe measures and pressured the sultan to disavow the Istiqlal and distance himself from nationalist claims. The break with France was consummated in 1951 and Sidi Mohammed concluded with the nationalists the pact of Tangier to fight for independence. The appointment of a new Resident General, General Augustin Guillaume , accentuated the dissension between Mohammed V and France. Further demonstrations turn into riots in Morocco in 1952, notably in Casablanca, while Sidi Mohammed gives the Moroccan cause an international audience at the UN with the support of the United States.[16]

Deposition and exile (1953–1955) edit

On 20 August 1953 (the eve of Eid al-Adha), the French colonial authorities forced Mohammed V, an important national symbol in the growing Moroccan independence movement, into exile in Corsica along with his family. His first cousin once removed, Mohammed Ben Aarafa, called the "French sultan," was made a puppet monarch and placed on the throne.[17] In response, Muhammad Zarqtuni bombed Casablanca's Central Market on Christmas Eve of that year.[17]

Mohammed V and his family were then transferred to Madagascar in January 1954. Mohammed V returned from exile on 16 November 1955, and was again recognized as Sultan after active opposition to the French protectorate. His triumphant return was for many the sign of the end of the colonial era.[18] The situation became so tense that in 1955, the Moroccan nationalists, who enjoyed support in Libya, Algeria (with the FLN) and Egypt forced the French government to negotiate and recall the sultan. In February 1956 he successfully negotiated with France and Spain for the independence of Morocco.

After independence (1956–1961) edit

Mohammed V supported the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) in the struggle for Algerian Independence and offered to facilitate the participation of FLN leaders in a conference with Habib Bourguiba in Tunis.[19] On October 22, 1956, French forces hijacked a Moroccan airplane carrying leaders of the FLN during the ongoing Algerian War.[20][19][21] The plane, which was carrying Ahmed Ben Bella, Hocine Aït Ahmed, and Mohamed Boudiaf, was destined to leave from Palma de Mallorca for Tunis, but French forces redirected the flight to occupied Algiers, where the FLN leaders were arrested.[19]

As Mohammed V returned to the throne, he suppressed many insurgencies, especially in the south and in the Rif. In 1957, he took the title of King of Morocco, to symbolise the unity of the country despite the divisions between Arabs and Berbers. In terms of domestic policy, upon his return he allowed the first congress of the Istiqlal, which formed various governments under his reign. He authorized the creation of trade unions, but the unrest and the strikes lead him to take full power in the last years of his reign.[16] His state visit to the United States later that year "strengthened his position as the kingdom's sole legitimate representative".[22] This way he managed to replace the members of the nationalist movement on the global stage and turned his trip into a great publicity success. This visit marked a strategic effort to align Morocco closely with the US, showcasing the monarchy's importance on the global stage.[22] He used various techniques to project the royal authority, such as personally thanking the nationalist movement's former supporters in the name of the Moroccan people.[22] Mohammed V also acted as patron to the International Meetings, conferences on contemporary issues and interfaith dialogue hosted at the Benedictine monastery of Toumliline that attracted scholars and intellectuals from all over the world.[23]

During his reign, the Moroccan Liberation Army waged war against Spain and France, and successfully captured most of Ifni as well as Cape Juby and parts of Spanish Sahara. With the treaty of Angra de Cintra, Morocco annexed Cape Juby and the surroundings of Ifni, while the rest of the remaining colony was ceded by Spain in 1969.[24]

Death (1961) edit

He died at 51 years old 26 February 1961 following complications of a minor operation he had undergone.[25]

Nisbah edit

Mohammed V's nisbah is Mohammed bin Yusef bin Hassan bin Muhammad bin Abd al-Rahman bin Hisham bin Muhammad bin Abdullah bin Ismail bin Sharif bin Ali bin Muhammad bin Ali bin Youssef bin Ali bin Al Hassan bin Muhammad bin Al Hassan bin Qasim bin Muhammad bin Abi Al Qasim bin Muhammad bin Al-Hassan bin Abdullah bin Muhammad bin Arafa bin Al-Hassan bin Abi Bakr bin Ali bin Al-Hasan bin Ahmed bin Ismail bin Al-Qasim bin Muhammad al-Nafs al-Zakiyya bin Abdullah al-Kamil bin Hassan al-Muthanna bin Hasan bin Ali bin Abi Talib bin Abd al-Muttalib bin Hashim.[26]

Legacy edit

The Mohammed V International Airport, Stade Mohammed V and Mohammed V Square in Casablanca, the Mohammed V Avenue, Mohammed V University and Mohammadia School of Engineering in Rabat, and the Mohammed V Mosque in Tangier are among numerous buildings, locales and institutions named after him. There's a mausoleum of Mohammed V in Rabat. There is an Avenue Mohammed V in nearly every Moroccan city and a major one in Tunis, Tunisia, and in Algiers, Algeria. The Mohammed V Palace in Conakry, Guinea, is named in his honour.

In December 2007, The Jewish Daily Forward reported on a secret diplomatic initiative by the Moroccan government to have Mohammed V admitted to the Righteous Among the Nations.[27]

Personal life edit

His first wife was Hanila bint Mamoun. They married in 1925.[28][29] She was the mother of his first daughter Fatima Zohra.

His second wife was his first cousin Abla bint Tahar. She was the daughter of Mohammed Tahar bin Hassan, son of Hassan I of Morocco. She married Mohammed V in 1928 and died in Rabat on 1 March 1992. She gave birth to five children: the future King Hassan II, Aisha, Malika, Abdallah and Nuzha.[30]

His third wife was Bahia bint Antar, with whom he had a daughter Amina.

Honours edit

- Order of Blood of the Tunisian Republic

- Grand Cross of the Legion of Honour of the French Republic (1927)[citation needed]

- Collar of the Order of Charles III of the Kingdom of Spain (1929)[31]

- Companion of the Order of Liberation of the French Republic (1945)[citation needed]

- Chief Commander of the Legion of Merit of the United States (1945)

- Grand Collar of the Imperial Order of the Yoke and Arrows of Francoist Spain (3 April 1956)[32]

- Grand Collar of the Order of Idris I of the Kingdom of Libya (1956)

- Collar of the Order of the Hashemites of the Kingdom of Iraq (1956)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of Umayyad of Syria (1960)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of Merit of Lebanon, special class (1960)

- Collar of the Order of the Nile of the Republic of Egypt (1960)

- Collar of the Order of Al-Hussein bin Ali of Jordan (1960)

- Grand Cordon of the Order of King Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia (1960)

See also edit

References edit

- ^ "Mohammed Al Hassan". geni_family_tree. 1909. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ "Mohammed Al Hassan, V". geni_family_tree. 10 August 1909. Retrieved 4 February 2024.

- ^ "محمد الخامس.. تعليم لا يليق بالملوك". 14 May 2014. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ photographique (commanditaire), Agence Rol Agence (1930). "8-7-30, [de g. à d.] El Mokri, le sultan, maréchal Liautey, M. Saint : [photographie de presse] / [Agence Rol]". Gallica. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Prince Moulay Hicham El Alaoui (9 April 2014). Journal d'un Prince Banni: Demain le Maroc (Grasset ed.). Grasset. ISBN 978-2-246-85166-0.

allait devenir la petite-fille préférée de Hassan II, le roi s'est émerveillé sans aucune gêne des yeux bleus de la nouveau-née. « Elle tient ça de son arrière-grand-mère turque », faisait-il remarquer en rappelant les yeux azur de la mère de Mohammed V

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Susan Gilson Miller (2013). A history of modern Morocco. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-62469-5. OCLC 855022840.

- ^ "الأمازيغية والاستعمار الفرنسي (24) .. السياسة البربرية والحرب". Hespress (in Arabic). 9 June 2018. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

- ^ a b Jessica M. Marglin. (2016). Across Legal Lines: Jews and Muslims in Modern Morocco (Yale University Press), p. 201.

- ^ Orit Bashkin & Daniel J. Schroeter. (2016). "Historical themes: Muslim-Jewish relations in the modern modern Middle East and North Africa" in The Routledge Handbook of Muslim-Jewish Relations (Routledge), p. 54.

- ^ a b c Susan Gilson Miller. (2013). A History of Modern Morocco (Cambridge University Press), pp. 142-143.

- ^ a b Abdelilah Bouasria. (2013). "The second coming of Morocco's 'Commander of the Faithful': Mohammed VI and Morocco's religious policy" in Contemporary Morocco: State, Politics and Society Under Mohammmed VI (eds. Bruce Maddy-Weitzman & Daniel Zisenwine), p. 42.

- ^ "KIVUNIM Convocation Honoring the Memory of King Mohammed V of Morocco". Kivunim. 24 December 2015.

- ^ Lawrence, Adria K. (2013). Imperial Rule and the Politics of Nationalism: Anti-Colonial Protest in the French Empire. Cambridge University Press. pp. 70–72. ISBN 978-1-107-03709-0.

- ^ Atlasinfo (6 April 2016). "Evènements du 7 avril 1947 à Casablanca, un tournant décisif dans la lutte pour la liberté et l'indépendance". Atlasinfo.fr: l'essentiel de l'actualité de la France et du Maghreb (in French). Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- ^ Safaa Kasraoui (10 April 2018). "Morocco Commemorates Sultan Mohammed V's 'Historic Visits' to Tangier and Tetouan". Morocco World News.

- ^ a b c Saïd., Bouamama (2014). Figures de la révolution africaine : de Kenyatta à Sankara. Découverte. ISBN 978-2-35522-037-1. OCLC 898169872.

- ^ a b "Histoire : Le Noël sanglant du marché central de Casablanca". Yabiladi (in French). Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ Stenner, David (2019). Globalizing Morocco : transnational activism and the postcolonial state. Stanford, California. p. 162. ISBN 978-1503608993.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Yabiladi.com. "22 October 1956 : Ben Bella, King Mohammed V and the story of the re-routed plane". en.yabiladi.com. Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ Essemlali, Mounya (2011). "Le Maroc entre la France et l'Algérie (1956-1962)". Relations Internationales. 146 (2): 77. doi:10.3917/ri.146.0077. ISSN 0335-2013.

- ^ Essa (22 October 2020). "أكتوبر في تاريخ المغرب أحداث وأهوال | المعطي منجب". القدس العربي (in Arabic). Retrieved 22 August 2022.

- ^ a b c Stenner, David (2019). Globalizing Morocco : transnational activism and the postcolonial state. Stanford, California. p. 189. ISBN 978-1503608993.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Foster, Elizabeth A.; Greenberg, Udi (29 August 2023). Decolonization and the Remaking of Christianity. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 114–115. ISBN 978-1-5128-2497-1. Retrieved 23 January 2024.

- ^ Pennell, C. R. (2000). Morocco Since 1830: A History. Hurst. ISBN 978-1-85065-273-1.

- ^ "Mohammed V of Morocco Dies at 51 After Surgery". The New York Times. 26 February 1961. Retrieved 13 June 2008.

King Mohammed V died today after a minor operation. He was 51 years old and had occupied the throne since 1927

- ^ "الإستقصا لأخبار دول المغرب الأقصى" (PDF) (ZIP archive) (in Arabic). 9 April 2020. Archived from the original on 9 April 2020. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ An Arab King Righteous Among the Nations?. The Forward, 12 December 2007

- ^ Triple royal wedding in Morocco

- ^ "Feue la princesse Lalla Fatima Zahra décedée le 10 aout 2014". Skyrock (in French). 13 August 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2018.

- ^ International Business Publications, Morocco Foreign Policy and Government Guide p. 84

- ^ Guía oficial de España, p. 211

- ^ Boletín Oficial del Estado

Bibliography edit

- David Bensoussan, Il était une fois le Maroc : témoignages du passé judéo-marocain, éd. du Lys, www.editionsdulys.ca, Montréal, 2010 (ISBN 2-922505-14-6); Second edition: www.iuniverse.com, Bloomington, IN, 2012, ISBN 978-1-4759-2608-8, 620p. ISBN 978-1-4759-2609-5 (ebook);

External links edit

- History of Morocco (in French) (archived 4 December 2008)