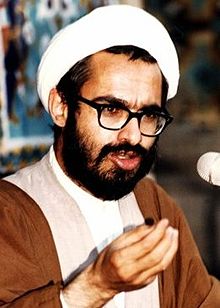

Mohammad Montazeri (Persian: محمد منتظری; 1944–28 June 1981) was an Iranian cleric and military figure. He was one of the founding members and early chiefs of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps. He was assassinated in a bombing in Tehran on 28 June 1981.

Mohammad Montazeri | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Abbas Mohammad Montazeri 1944 |

| Died | 28 June 1981 (aged 37) |

| Cause of death | Bombing |

| Resting place | Fatima Masumeh Shrine, Qom |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Occupation | Cleric |

| Years active | 1960s–1981 |

| Parents |

|

Early life and education edit

Born in Najafabad in 1944, Montazeri was the oldest son of Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri.[1][2][3] He had two brothers and two sisters.[4]

In 1963 Montazeri attended religious seminars in Qum together with his long-term confidant Mehdi Hashemi and Mehdi's brother Hadi Hashemi who future husband of Montazeri's sister.[5]

Career and activities edit

Montazeri was a low-ranking and radical cleric.[1] He began opposition activities against Mohammad Reza Pahlavi after the June 1963 events that led to the exile of Khomeini.[6] His father and he were both arrested by the Shah's security forces in March 1966.[7] In prison Mohammad was tortured and released in 1968.[6] He left Iran for Pakistan.[8] Then he settled in Najaf, Iraq, in 1971 and stayed there until 1975.[6] Next he lived in Afghanistan and in other cities of Iraq.[6]

He headed an armed group that was based in Syria and Lebanon and fought against Israeli forces.[8][9] The group, namely People's Revolutionary Organization of the Islamic Republic of Iran, was founded by Montazeri and Ali Akbar Mohtashamipur with the aim of assisting liberation movements in Muslim countries.[10]

Montazeri was trained in the Fatah camps in Lebanon.[3][11] In addition, he fought with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) and other Palestinian and Shiite armed groups in the country.[12] Montazeri was one of the three Iranian key officials along with Mostafa Chamran and Mohtashamipur who strengthened Iran's commitment to Lebanon.[13] Montazeri was called Abu Ahmad by Lebanese people.[14] Montazeri, Mohtashamipur and Jalal al-Din Farsi suggested that Iranian army should be sent to southern Lebanon to fight the Israeli army which had been invading the region.[15] Their proposal was not endorsed by the Amal Movement which considered it as an interference in Lebanon's internal affairs.[15] Montazeri also travelled to Europe during this period.[6]

In the mid-1970s Montazeri formed his base in Syria and continued his close relations with the PLO and the Libyan ruler Muammar Gaddafi’s secret service.[16] In 1978 he occupied the Mehrabad airport of Tehran with his 200 armed followers and demanded to go to Libya to search for Musa Al Sadr, a Lebanese Shia cleric who disappeared in Libya in August 1978.[17] He visited Ayatollah Khomeini when the latter was in exile in Paris.[18] Before the 1979 Iranian revolution he was one of the people who promoted the idea of the establishment of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards.[12][19]

During the revolutionary process, Montazeri was called "Ayatollah Ringo"[2] and "Red Sheikh".[20] In order to export Islamic revolution to other countries he and Mehdi Hashemi founded one of the earliest groups, the SATJA, in the spring of 1979.[14][21] In December 1979 he organized a campaign to support and join the Palestinian militants, fighting in the Lebanese civil war.[17] His activities in the SATJA caused conflicts with the government, and he was forced to disband it.[21]

Then Montazeri and Hashemi joined the Guards.[21] Montazeri headed a faction of the Guards in Tehran that functioned as a strong arm of the Supreme Leader Khomeini.[9] It was called Freedom Movements Unit.[14] In 1981 this faction was transformed into the office of liberation movements (OLM) which was first led by him and after his death, by Hashemi.[12][22] An account with the name liberation movements was opened in the Melli Bank to get financial support from Iranians.[9] The OLM put into practice the Iranian support for the Shi‘a movements in Iraq and the Gulf[22] as well as those in Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and Afghanistan.[23]

At the founding and institutionalization phase of the Guards Montazeri became a member of the Revolutionary Guards Leadership Council in 1979 which was formed by the Revolutionary Council to oversee the future tasks of the Guard.[24] He publicly declared in 1980 that the IRGC personnel "were awaiting deployment from Damascus."[25]

Montazeri joined and led the Muslim People's Republic Party[26] and became a member of the first Majlis in March 1980.[27][28] On the other hand, his party was disbanded after its members were either arrested or executed.[26] In addition, Montazeri served at the supreme defense council[29] and was the prayer leader in Tehran until his death.[30]

Views edit

Montazeri was one of the most radical followers of Ayatollah Khomeini.[31] Before the Iranian revolution he was close ally of Muammar Gaddafi and advocated strong ties with Libya.[31] And, he did not support the approach of the Amal movement and Musa Al Sadr due to their being non-revolutionary.[6][8] Montazeri was also a fierce critic of the interim government led by Mahdi Bazargan due to the same reason.[8]

Both Montazeri and his father actively encouraged the rebellion of Shia Muslims against the governments in the Muslim countries and also, strongly argued for the export of the Islamic regime to other countries, often called "Islamic Internationale".[3][9] The latter goal was mostly achieved through the OLM,[12][22] and it is one of two pillars of ideology guided the revolution along with the propagation of Islam.[32] In addition, he argued that all Muslims could enter Islamic states without passport or visas.[33]

Montazeri supported the development of links with Shia Muslims in Lebanon.[19] He tried to make Iran a key player in the Palestinian-Israeli conflict.[12] Just three days before his death, he argued for the execution of the followers of the ousted President Abolhassan Banisadr.[30]

Controversy edit

At the initial phase of the Iranian revolution the activities of the Montazeri's group, SATJA, led to tensions between Montazeri and both the Guards's leadership and the provisional government.[21] His father, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, publicly reprimanded him and stated that Mohammad had poor mental health because he had been tortured by the former Shah's secret police.[21] Eventually, elder Montazeri disassociated himself from his son’s activities.[20]

Mohammad Montazeri was part of the Libya-friendly group in the court of Khomeini, and there was a feud between his group and the faction, called "Syrian mafia", led by Sadegh Ghotbzadeh.[34] Ghotbzadeh's faction was called previously the Liberation Movement of Iran (LMI), and Mostafa Chamran was also part of it.[31] In addition, Montazeri had serious disagreements with Ayatollah Mohammad Beheshti, cofounder of the Islamic Republican Party.[9]

Death edit

Montazeri was killed in a bombing at the central headquarters of the then ruling party, Islamic Republican Party, in Tehran on 28 June 1981.[35] The Islamic Republic of Iran suspected various organizations and individuals, including SAVAK, the Iraqi regime, the People's Mujahedin of Iran, the United States, royalist army officers, and "internal mercenaries". The death toll in the attack was 73, including Behesti, cabinet ministers and the members of the Majlis.[30][36] A state funeral was held for the victims on 30 June and a week of mourning was proclaimed.[30] Montazeri was buried in the Fatima Masumeh Shrine in Qom where his father would also be buried on 21 December 2009.[37]

Four Iraqi agents and Mehdi Tafari were executed for the incident.[19][38][39]

Legacy edit

A street in Qom was named after him, Martyr Mohammad Montazeri boulevard.[40]

References edit

- ^ a b Mehdi Khalaji (February 2012). "Supreme Succession. Who Will Lead Post-Khamenei Iran" (Policy Focus (No. 117)). The Washington Institute. Washington DC.

- ^ a b Steven O'Hern (2012). Iran's Revolutionary Guard: The Threat that Grows While America Sleeps. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, Inc. p. 216. ISBN 978-1-59797-701-2.

- ^ a b c Dominique Avon; Anaïs-Trissa Khatchadourian; Jane Marie Todd (2012). Hezbollah: A History of the "Party of God". Cambridge, MA; London: Harvard University Press. p. 207. ISBN 978-0-674-06752-3.

- ^ Michael R. Fischbach, ed. (200). "Montazeri, Hossein Ali (1922–)". Biographical Encyclopedia of the Modern Middle East and North Africa. Thomson Gale. ISBN 978-1-4144-1889-6.

- ^ Ulrich von Schwerin (2015). "Mehdi Hashemi and the Iran-Contra-Affair". British Journal of Middle Eastern Studies. 42 (4): 522. doi:10.1080/13530194.2015.1028520. S2CID 218602348.

- ^ a b c d e f Rula Jurdi Abisaab (2006). "The Cleric as Organic Intellectual: Revolutionary Shiism in the Lebanese Hawzas". In Houchang Chehabi (ed.). Distant Relations: Iran and Lebanon in the Last 500 Years. Oxford; London: I.B. Tauris. p. 182. ISBN 978-1-86064-561-7.

- ^ "Seyed Mohammad Khatami". Iran Chamber Society. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d Mohammad Ataie (Summer 2013). "Revolutionary Iran's 1979 endeavor in Lebanon". Middle East Policy. XX (2): 137–157. doi:10.1111/mepo.12026.

- ^ a b c d e Ali Alfoneh (2013). Iran Unveiled: How the Revolutionary Guards Is Transforming Iran from Theocracy into Military Dictatorship. Washington, DC: AEI Press. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-8447-7255-4.

- ^ Shahryar Sadr (July 2010). "How Hezbollah Founder Fell Foul of Iranian Regime". IRN (43). Archived from the original on 10 October 2014.

- ^ Robin Wright (21 December 2009). "Iran's Opposition Loses a Mentor but Gains a Martyr". Time. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d e Afshon P. Ostovar (2009). Guardians of the Islamic Revolution Ideology, Politics, and the Development of Military Power in Iran (1979–2009) (PhD thesis). University of Michigan. hdl:2027.42/64683.

- ^ Ray Takeyh (2009). Guardians of the Revolution:Iran and the World in the Age of the Ayatollahs. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-19-979313-6.

- ^ a b c Mohammad Ataie (Summer 2013). "Revolutionary Iran's 1979 Endeavor in Lebanon". Middle East Policy. XX (2): 137–157. doi:10.1111/mepo.12026.

- ^ a b Roschanack Shaery-Eisenlohr (February 2007). "Imagining Shi'ite Iran: Transnationalism and Religious Authenticity in the Muslim World". Iranian Studies. 40 (1): 21. doi:10.1080/00210860601138608. JSTOR 4311873. S2CID 145569571.

- ^ Darioush Bayandor (2019). The Shah, the Islamic Revolution and the United States. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 151. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-96119-4_6. ISBN 978-3-319-96119-4.

- ^ a b "1,000 Iranians prepare to fight Israelis". The Phoenix. Tehran. AP. 12 December 1979. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ Baqer Moin (1999). Khomeini: Life of the Ayatollah. London; New York: I.B.Tauris. p. 194. ISBN 978-1-85043-128-2.

- ^ a b c Meir Javedanfar (21 December 2009). "Filling Montazeri's shoes in Iran". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ a b Gary G. Sick (Spring 1987). "Iran's Quest for Superpower Status". Foreign Affairs.

- ^ a b c d e Helen Chapin Metz, ed. (1987). "Concept of Export of Revolution". Iran: A Country Study. Washington, DC: GPO for the Library of Congress. ISBN 9780160867019.

- ^ a b c Toby Matthiesen (Spring 2010). "Hizbullah al-Hijaz: A History of The Most Radical Saudi Shi'a Opposition Group". The Middle East Journal. 64 (2): 179–197. doi:10.3751/64.2.11. S2CID 143684557.

- ^ Laurence Louër (2012). Transnational Shia Politics: Religious and Political Networks in the Gulf. London: Hurst Publishers. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-84904-214-7.

- ^ Amir Farshad Ebrahim (7 September 2010). "IRGC History". Iran Briefing. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ Abbas William Samii (Winter 2008). "A Stable Structure on Shifting Sands: Assessing the Hizbullah-Iran-Syria Relationship". The Middle East Journal. 62 (1): 32–53. doi:10.3751/62.1.12.

- ^ a b Eric Rouleau (1980). "Khomenei's Iran". Foreign Affairs. 59 (1).

- ^ Bahman Baktiari (1996). Parliamentary Politics in Revolutionary Iran: The Institutionalization of Factional Politics. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-8130-1461-6.

- ^ Arash Reisinezhad (2019). The Shah of Iran, the Iraqi Kurds, and the Lebanese Shia. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 241. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-89947-3. ISBN 978-3-319-89947-3. S2CID 187523435.

- ^ "Khomeini plans to oust cleric". Calgary Herald. Tehran. Reuters. 18 May 1981. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ a b c d "64 leaders slain Iranian bombing". The Tuscaloosa News. Beirut. AP. 29 June 1981. p. 2. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ a b c Tony Badran (8 September 2010). "Moussa Sadr and the Islamic Revolution in Iran… and Lebanon". NOW News. Archived from the original on 10 September 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ^ Shmuel Bar (2009). "Iranian terrorist policy and "export of revolution"" (PDF). Interdisciplinary Center.

- ^ Shaul Bakhash (1989). "The Islamic Republic of Iran, 1979-1989". The Wilson Quarterly. 13 (4): 54–62. JSTOR 40257945.

- ^ Mark Gayn (20 December 1979). "Into the depths of a boiling caldron". Edmonton Journal. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ "33 High Iranian Officials Die in Bombing at Party Meeting; Chief Judge is among Victims". The New York Times. 29 June 1981.

- ^ Semira N. Nikou. "Timeline of Iran's Political Events". United States Institute of Peace. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ "Funeral of A Revered Ayatollah, Hossein Ali Montazeri". Payvand. 21 December 2009. Archived from the original on 30 September 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2013.

- ^ Ervand Abrahamian (1989). Radical Islam: The Iranian Mojahedin. London: I.B. Tauris. pp. 219–220. ISBN 978-1-85043-077-3.

- ^ "Iranians mass for funeral". The Day. 30 June 1981. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

- ^ "Million-Man Show of Force". Rooz. 23 December 2009. Retrieved 27 July 2013.

External links edit

- Media related to Mohammad Montazeri at Wikimedia Commons