Mizane Birhan is a tabia or municipality in the Dogu'a Tembien district of the Tigray Region of Ethiopia. The tabia centre is in Ma’idi village, located approximately 13 km to the southeast of the woreda town Hagere Selam (as the crow flies).

Mizane Birhan | |

|---|---|

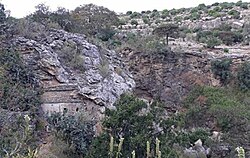

Rock church in Mizane Birhan | |

| Coordinates: 13°37′N 39°16′E / 13.617°N 39.267°E | |

| Country | Ethiopia |

| Region | Tigray |

| Zone | Debub Misraqawi (Southeastern) |

| Woreda | Dogu'a Tembien |

| Area | |

| • Total | 29.79 km2 (11.50 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 2,280 m (7,480 ft) |

| Population (2007) | |

| • Total | 7,195 |

| • Density | 242/km2 (630/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

Geography edit

The tabia is astride the Imba Dogu’a ridge, between valleys of Rubaksa and Ruba Bich’i Rivers. The highest peak is Imba Dogu’a (2620 m a.s.l.) and the lowest place at east is along Ruba Bich’i (1960 m a.s.l.) and at west 2020 m, down from Addi Welo.

Geology edit

From the higher to the lower locations, the following geological formations are present:[1]

- Mekelle Dolerite,[2] forming the large Imba Dogu’a batholite that dominates Mizane Birhan

- Upper basalt

- Interbedded lacustrine deposits

- Lower basalt

- Amba Aradam Formation

- Agula Shale[3]

- Antalo Limestone: a large quarry south of Ma’idi

- Quaternary alluvium and freshwater tufa[4]

Geomorphology and soils edit

The main geomorphic unit is the gently undulating Agula shale plateau with dolerite. Corresponding soil types are:[5]

- Dominant soil type: stony, dark cracking clays with good natural fertility (Vertic Cambisol)

- Associated soil types

- Inclusions

Climate and hydrology edit

Climate and meteorology edit

The rainfall pattern shows a very high seasonality with 70 to 80% of the annual rain falling in July and August. Mean temperature in Ma’idi is 19.8 °C, oscillating between average daily minimum of 11.1 °C and maximum of 28 °C. The contrasts between day and night air temperatures are much larger than seasonal contrasts.[6]

Rivers edit

The Giba River is the most important river in the surroundings of the tabia. It flows towards Tekezze River and further on to the Nile.[7] The drainage network of the tabia is organised as follows:[8]

- Giba River, with tributaries:

- Ruba Bich’i River, in tabia Addi Azmera

- Imba Wahti River, draining the eastern part of Mizane Birhan

- Rubaksa River, in tabia Mika'el Abiy

- May Wikul River, in Mizane Birhan

- Tsigaba River, draining the northern part of Mizane Birhan

- Ruba Bich’i River, in tabia Addi Azmera

Whereas they are (nearly) dry during most of the year, during the main rainy season, these rivers carry high runoff discharges, sometimes in the form of flash floods. Especially at the beginning of the rainy season, they are brown-coloured, evidencing high soil erosion rates.

Springs edit

As there are no permanent rivers, the presence of springs is of utmost importance for the local people. The main springs in the tabia are:[9]

- Gedel Negedu in Lafa

- May Wkul in Ma’idi

- Gemgema in Merhib

Water harvesting edit

In this area with rains that last only for a couple of months per year, reservoirs of different sizes allow harvesting runoff from the rainy season for further use in the dry season.

- Traditional surface water harvesting ponds, particularly in places without permanent springs, called rahaya

- Horoyo, household ponds, recently constructed through campaigns[10]

Vegetation and exclosures edit

The tabia holds several exclosures, areas that are set aside for regreening.[11] Wood harvesting and livestock range are not allowed there. Besides effects on biodiversity,[12][13][14] water infiltration, protection from flooding, sediment deposition,[15] carbon sequestration,[16] people commonly have economic benefits from these exclosures through grass harvesting, beekeeping and other non-timber forest products.[17] The local inhabitants also consider it as “land set aside for future generations”.[18] In this tabia, some exclosures are managed by the EthioTrees project. They have as an additional benefit that the villagers receive carbon credits for the sequestered CO2,[19] as part of a carbon offset programme.[20] The revenues are then reinvested in the villages, according to the priorities of the communities;[21] it may be for an additional class in the village school, a water pond, or conservation in the exclosures. Lafa (exclosure), near the homonymous village (44.44 ha) is managed by the Ethiotrees project.[22]

Settlements edit

The tabia centre Ma’idi holds a few administrative offices, a health post, a primary school, and some small shops.[9] There are a few more primary schools across the tabia. The main other populated places are:[8]

- Merhib

- Addi Welo

- Lafa

- May Shewani

- Neged Negedu

Agriculture and livelihood edit

The population lives essentially from crop farming, supplemented with off-season work in nearby towns. The land is dominated by farmlands which are clearly demarcated and are cropped every year. Hence the agricultural system is a permanent upland farming system.[23] The farmers have adapted their cropping systems to the spatio-temporal variability in rainfall.[24]

History and culture edit

History edit

The history of the tabia is strongly confounded with the history of Tembien.

Religion and churches edit

Most inhabitants are Orthodox Christians. The following churches are located in the tabia:

- Lafa Gebri’el

- Neged Negedu Mika’el

- Ma’idi

- Addi Welo Teklehaimanot

- Merhib Mika’el

Inda Siwa, the local beer houses edit

In the main villages, there are traditional beer houses (Inda Siwa), often in unique settings, where people socialise. Well known in the tabia are[9]

- Roman Gebreayezgi at Ma’idi

- Nigas Dimtsu at Ma’idi

- Haymanot Gidey at Ma’idi

Roads and communication edit

The main road Mekelle – Hagere Selam – Abiy Addi runs 8 km north of the tabia. There is a good dirt road across the tabia with regular bus services to the main asphalt road and directly to Mekelle or Hagere Selam these towns.

Tourism edit

Its mountainous nature and proximity to Mekelle make the tabia fit for tourism.[25] As compared to many other mountain areas in Ethiopia the villages are quite accessible, and during walks visitors may be invited for coffee, lunch or even for an overnight stay in a rural homestead.[26]

Touristic attraction edit

The Lafa Gebri’al rock church (13°35.87′N 39°17.25′E / 13.59783°N 39.28750°E) is now disused. It was hewn in a tufa plug. The church boosts a semi-circular wooden arch of approx. 1.5 metre across (in one piece).[27] A new church has been constructed nearby.

Geotouristic sites edit

The large batholite made of dolerite, the high variability of geological formations and the rugged topography invite for geological and geographic tourism or "geotourism".[28]

Birdwatching edit

Birdwatching can be done particularly in the bushlands of the eastern slopes op Imba Dogu’a.[29] in the tabia and mapped.[8] The main Dogu'a Tembien page holds more details on the bird species.

Trekking routes edit

Trekking routes have been established in this tabia.[27] The tracks are not marked on the ground but can be followed using downloaded .GPX files.[30]

- Trek 13, from Ma’idi towards Hagere Selam, largely through limestone landscapes

- Trek 17, from Togogwa along Lafa and the eastern slopes of Imba Dogu’a towards Merhib

See also edit

- Dogu'a Tembien district.

References edit

- ^ Sembroni, A.; Molin, P.; Dramis, F. (2019). Regional geology of the Dogu'a Tembien massif. In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains — The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ Tefera, M.; Chernet, T.; Haro, W. Geological Map of Ethiopia (1:2,000,000). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopian Institute of Geological Survey.

- ^ Bosellini, A.; Russo, A.; Fantozzi, P.; Assefa, G.; Tadesse, S. (1997). "The Mesozoic succession of the Mekelle Outlier (Tigrai Province, Ethiopia)". Mem. Sci. Geol. 49: 95–116.

- ^ Moeyersons, J. and colleagues (2006). "Age and backfill/overfill stratigraphy of two tufa dams, Tigray Highlands, Ethiopia: Evidence for Late Pleistocene and Holocene wet conditions". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 230 (1–2): 162–178. Bibcode:2006PPP...230..165M. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2005.07.013.

- ^ Nyssen, Jan; Tielens, Sander; Gebreyohannes, Tesfamichael; Araya, Tigist; Teka, Kassa; Van De Wauw, Johan; Degeyndt, Karen; Descheemaeker, Katrien; Amare, Kassa; Haile, Mitiku; Zenebe, Amanuel; Munro, Neil; Walraevens, Kristine; Gebrehiwot, Kindeya; Poesen, Jean; Frankl, Amaury; Tsegay, Alemtsehay; Deckers, Jozef (2019). "Understanding spatial patterns of soils for sustainable agriculture in northern Ethiopia's tropical mountains". PLOS ONE. 14 (10): e0224041. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1424041N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224041. PMC 6804989. PMID 31639144.

- ^ Jacob, M. and colleagues (2019). "Dogu'a Tembien's Tropical Mountain Climate". Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains. GeoGuide. SpringerNature. pp. 45–61. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_3. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6. S2CID 199105560.

- ^ Amanuel Zenebe, and colleagues (2019). "The Giba, Tanqwa and Tsaliet Rivers in the Headwaters of the Tekezze Basin". Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains. GeoGuide. SpringerNature. pp. 215–230. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_14. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6. S2CID 199099067.

- ^ a b c Jacob, M. and colleagues (2019). Geo-trekking map of Dogu'a Tembien (1:50,000). In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains — The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ a b c What do we hear from the farmers in Dogu'a Tembien? [in Tigrinya]. Hagere Selam, Ethiopia. 2016. p. 100.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Developers and farmers intertwining interventions: the case of rainwater harvesting and food-for-work in Degua Temben, Tigray, Ethiopia

- ^ Aerts, R; Nyssen, J; Mitiku Haile (2009). "On the difference between "exclosures" and "enclosures" in ecology and the environment". Journal of Arid Environments. 73 (8): 762–763. Bibcode:2009JArEn..73..762A. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2009.01.006.

- ^ Aerts, R.; Lerouge, F.; November, E. (2019). Birds of forests and open woodlands in the highlands of Dogu'a Tembien. In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ Mastewal Yami, and colleagues (2007). "Impact of Area Enclosures on Density and Diversity of Large Wild Mammals: The Case of May Ba'ati, Douga Tembien Woreda, Central Tigray, Ethiopia". East African Journal of Sciences. 1: 1–14.

- ^ Aerts, R; Lerouge, F; November, E; Lens, L; Hermy, M; Muys, B (2008). "Land rehabilitation and the conservation of birds in a degraded Afromontane landscape in northern Ethiopia". Biodiversity and Conservation. 17: 53–69. doi:10.1007/s10531-007-9230-2. S2CID 37489450.

- ^ Descheemaeker, K. and colleagues (2006). "Sediment deposition and pedogenesis in exclosures in the Tigray Highlands, Ethiopia". Geoderma. 132 (3–4): 291–314. Bibcode:2006Geode.132..291D. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2005.04.027.

- ^ Wolde Mekuria, and colleagues (2011). "Restoration of Ecosystem Carbon Stocks Following Exclosure Establishment in Communal Grazing Lands in Tigray, Ethiopia". Soil Science Society of America Journal. 75 (1): 246–256. Bibcode:2011SSASJ..75..246M. doi:10.2136/sssaj2010.0176.

- ^ Bedru Babulo, and colleagues (2006). "Economic valuation methods of forest rehabilitation in exclosures". Journal of the Drylands. 1: 165–170.

- ^ Jacob, M. and colleagues (2019). Exclosures as Primary Option for Reforestation in Dogu'a Tembien. In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ Reubens, B. and colleagues (2019). Research-based development projects in Dogu'a Tembien. In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ EthioTrees on Plan Vivo website

- ^ EthioTrees on Davines website

- ^ De Deyn, Jonathan (2019). Benefits of reforestation on Carbon storage and water infiltration in the context of climate mitigation in North Ethiopia. Master thesis, Ghent University, Belgium.

- ^ Nyssen, J.; Naudts, J.; De Geyndt, K.; Haile, Mitiku; Poesen, J.; Moeyersons, J.; Deckers, J. (2008). "Soils and land use in the Tigray highlands (Northern Ethiopia)". Land Degradation and Development. 19 (3): 257–274. doi:10.1002/ldr.840. S2CID 128492271.

- ^ Frankl, A. and colleagues (2013). "The effect of rainfall on spatio‐temporal variability in cropping systems and duration of crop cover in the Northern Ethiopian Highlands". Soil Use and Management. 29 (3): 374–383. doi:10.1111/sum.12041. hdl:1854/LU-3123393. S2CID 95207289.

- ^ Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains — The Dogu'a Tembien District. GeoGuide. SpringerNature. 2019. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6. S2CID 199294303.

- ^ Nyssen, Jan (2019). "Logistics for the Trekker in a Rural Mountain District of Northern Ethiopia". Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains. GeoGuide. Springer-Nature. pp. 537–556. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_37. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6. S2CID 199198251.

- ^ a b Description of trekking routes in Dogu'a Tembien. In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains - The Dogu'a Tembien District. GeoGuide. SpringerNature. 2019. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6. S2CID 199294303.

- ^ Miruts Hagos and colleagues (2019). "Geosites, Geoheritage, Human-Environment Interactions, and Sustainable Geotourism in Dogu'a Tembien". Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains. GeoGuide. SpringerNature. pp. 3–27. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_1. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6. S2CID 199095921.

- ^ Aerts, R.; Lerouge, F.; November, E. (2019). Birds of forests and open woodlands in the highlands of Dogu'a Tembien. In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains – The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- ^ "Public GPS traces tagged with nyssen-jacob-frankl". OpenStreetMap. Retrieved 2019-10-11.