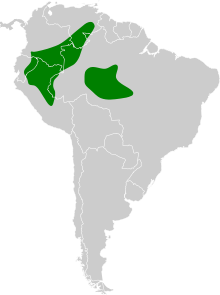

The pearly antshrike (Megastictus margaritatus) is a species of bird in subfamily Thamnophilinae of family Thamnophilidae, the "typical antbirds".[2] It is found in Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru, and Venezuela.[3]

| Pearly antshrike | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Thamnophilidae |

| Genus: | Megastictus Ridgway, 1909 |

| Species: | M. margaritatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Megastictus margaritatus (PL Sclater, 1855)

| |

| |

Taxonomy and systematics edit

The pearly antshrike was described by the English zoologist Philip Sclater in 1855 and given the binomial name Myrmeciza margaritatus.[4] The genus Megastictus was erected by the American ornithologist Robert Ridgway in 1909.[5]

The pearly antshrike is the only member of genus Megastictus and has no subspecies.[2]

Description edit

The pearly antshrike is 12 to 13 cm (4.7 to 5.1 in) long and weighs 18 to 21 g (0.63 to 0.74 oz). Adult males have a gray face, crown, and upperparts with white tips on the uppertail coverts. Their wings are black with large round white spots on the coverts and tertials. Their tail is black with white feather tips. Their underparts are gray that is lighter on the chin, throat, and the belly center. Adult females have a yellowish brown face, crown, and upperparts with a blackish tinge on the crown and pale buffish spots on the uppertail coverts. Their wings and tail are yellowish brown and spotted with pale buffish where the male has white spots. Their flight feathers have ochraceous edges. Their underparts are cinnamon-tinged ochraceous that is palest on the throat and belly center.[6][7][8][9]

Distribution and habitat edit

The pearly antshrike has a disjunct distribution. One population is found in eastern and southern Colombia, southern Venezuela, eastern Ecuador, northeastern and east-central Peru, and northwestern Brazil to the upper Rio Negro. The other is in Brazil south of the Amazon from the Rio Juruá to the watershed of the Rio Madeira. The pearly antshrike inhabits the understorey of evergreen forest and nearby secondary woodland. In Ecuador it favors terra firme and in most locations forest on sandy soils. It has been observed on the edges of lagoons but apparently does not frequent riverside forest. In elevation it reaches 1,200 m (3,900 ft) in Brazil and the tepui region of Venezuela. It occurs mostly below 300 m (1,000 ft) in Ecuador and 400 m (1,300 ft) in Colombia.[6][7][8][9]

Behavior edit

Movement edit

The pearly antshrike is believed to be a year-round resident throughout its range.[6]

Feeding edit

The pearly antshrike's diet has not been detailed but is known to include insects and other arthropods. It mostly forages singly, in pairs, and family groups, and seldom as a member of a mixed-species feeding flock. It typically forages between 2 and 6 m (7 and 20 ft) above the ground but also as low as 1 m (3 ft) and as high as 10 m (30 ft). It captures prey with an upward sally from a perch to capture it from foliage, stems, and vines, by sallying to capture it in mid-air, and by hover-gleaning.[6][7][8][9]

Breeding edit

A nesting pair of pearly antshrikes was recorded in August in Brazil but the species' breeding season is otherwise unknown. One nest was a cup made of plant fibers, rootlets, and dead leaves, suspended from a fork low down in a sapling. It resembled a pile of dead leaves or debris. The clutch size was two eggs and the male was observed incubating during the day. The incubation period, time to fledging, and other details of parental care are not known.[6]

Vocalization edit

The pearly antshrike's song is "2–3 slowly delivered whistles, slurred up and down, followed by 6–7 flat raspy notes at much faster pace".[6] It has been written as "whee? whee? whee? jrr-jrr-jrr-jrr-jrr-jrr".[8] Its alarm or contact call is "whistled, upslurred 'wheet' notes" and it makes a "hard rattle" in agonistic encounters.[6]

Status edit

The IUCN has assessed the pearly antshrike as being of Least Concern. It has a very large range. Its population size is not known and is believed to be decreasing. No immediate threats have been identified.[1] It is considered rare to locally uncommon in most areas, and its distribution appears to be patchy. "Existence of vast areas of relatively inaccessible, intact, and seemingly suitable habitat should guarantee that this species is not at risk."[6]

References edit

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2016). "Pearly Antshrike Megastictus margaritatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22701352A93825469. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22701352A93825469.en. Retrieved 26 February 2024.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (January 2024). "Antbirds". IOC World Bird List. v 14.1. Retrieved January 4, 2024.

- ^ Remsen, J. V., Jr., J. I. Areta, E. Bonaccorso, S. Claramunt, G. Del-Rio, A. Jaramillo, D. F. Lane, M. B. Robbins, F. G. Stiles, and K. J. Zimmer. Version 26 November 2023. Species Lists of Birds for South American Countries and Territories. https://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCCountryLists.htm retrieved November 27, 2023

- ^ Sclater, Philip L. (1854). "Descriptions of six new species of birds of the subfamily Formicarinae". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 22 (275): 253–255 [253] Plate 71. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1854.tb07273.x. The title page gives the year 1854 but the volume was not published until the following year.

- ^ Ridgway, Robert (1909). "New genera, species and subspecies of Formicariidae, Furnariidae, and Dendrocolaptidae". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 22: 69–74 [69].

- ^ a b c d e f g h Zimmer, K. and M.L. Isler (2020). Pearly Antshrike (Megastictus margaritatus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, J. Sargatal, D. A. Christie, and E. de Juana, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.peaant1.01 retrieved February 25, 2024

- ^ a b c van Perlo, Ber (2009). A Field Guide to the Birds of Brazil. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 232–233. ISBN 978-0-19-530155-7.

- ^ a b c d Ridgely, Robert S.; Greenfield, Paul J. (2001). The Birds of Ecuador: Field Guide. Vol. II. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. p. 398. ISBN 978-0-8014-8721-7.

- ^ a b c McMullan, Miles; Donegan, Thomas M.; Quevedo, Alonso (2010). Field Guide to the Birds of Colombia. Bogotá: Fundación ProAves. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-9827615-0-2.