The Mars Polar Lander, also known as the Mars Surveyor '98 Lander, was a 290-kilogram robotic spacecraft lander launched by NASA on January 3, 1999, to study the soil and climate of Planum Australe, a region near the south pole on Mars. It formed part of the Mars Surveyor '98 mission. On December 3, 1999, however, after the descent phase was expected to be complete, the lander failed to reestablish communication with Earth. A post-mortem analysis determined the most likely cause of the mishap was premature termination of the engine firing prior to the lander touching the surface, causing it to strike the planet at a high velocity.[2]

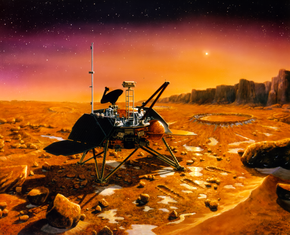

Artist's depiction of the Mars Polar Lander on Mars | |

| Names | Mars Surveyor '98 |

|---|---|

| Mission type | Lander |

| Operator | NASA / JPL |

| COSPAR ID | 1999-001A |

| SATCAT no. | 25605 |

| Website | Mars Polar Lander website |

| Mission duration | 334 days Mission failure |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Martin Marietta |

| Launch mass | 583 kg[1] |

| Power | 200 W solar array and NiH2 battery |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 20:21:10, January 3, 1999 (UTC) |

| Rocket | Delta II 7425-9.5 |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral AFS SLC-17A |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | communication failure after landing |

| Declared | January 17, 2000 |

| Last contact | 20:00, December 3, 1999 (UTC) |

| Mars lander | |

| Landing date | ~20:15 UTC ERT, December 3, 1999 |

| Landing site | Ultimi Scopuli, 76°S 195°W / 76°S 195°W (projected) |

Mars Surveyor 98 mission logo | |

The total cost of the Mars Polar Lander was US$165 million. Spacecraft development cost US$110 million, launch was estimated at US$45 million, and mission operations at US$10 million.[3]

Mission background edit

History edit

As part of the Mars Surveyor '98 mission, a lander was sought as a way to gather climate data from the ground in conjunction with an orbiter. NASA suspected that a large quantity of frozen water may exist under a thin layer of dust at the south pole. In planning the Mars Polar Lander, the potential water content in the Martian south pole was the strongest determining factor for choosing a landing location.[4] A CD-ROM containing the names of one million children from around the world was placed on board the spacecraft as part of the "Send Your Name to Mars" program designed to encourage interest in the space program among children.[5]

The primary objectives of the mission were to:[6]

- land on the layered terrain in the south polar region of Mars;

- search for evidence related to ancient climates and more recent periodic climate change;

- give a picture of the current climate and seasonal change at high latitudes and, in particular, the exchange of water vapor between the atmosphere and ground;

- search for near-surface ground ice in the polar regions, and analyze the soil for physically and chemically bound carbon dioxide and water; and

- study surface morphology (forms and structures), geology, topography, and weather of the landing site.

Deep Space 2 probes edit

The Mars Polar Lander carried two small, identical impactor probes known as "Deep Space 2 A and B". The probes were intended to strike the surface with a high velocity at approximately 73°S 210°W / 73°S 210°W to penetrate the Martian soil and study the subsurface composition up to a meter in depth. However, after entering the Martian atmosphere, attempts to contact the probes failed.[4]

Deep Space 2 was funded by the New Millennium Program, and their development costs was US$28 million.[3]

Spacecraft design edit

The spacecraft measured 3.6 meters wide and 1.06 meters tall with the legs and solar arrays fully deployed. The base was primarily constructed with an aluminum honeycomb deck, composite graphite–epoxy sheets forming the edge, and three aluminum legs. During landing, the legs were to deploy from stowed position with compression springs and absorb the force of the landing with crushable aluminum honeycomb inserts in each leg. On the deck of the lander, a small thermal Faraday cage enclosure housed the computer, power distribution electronics and batteries, telecommunication electronics, and the capillary pump loop heat pipe (LHP) components, which maintained operable temperature. Each of these components included redundant units in the event that one may fail.[4][7][8]

Attitude control and propulsion edit

While traveling to Mars, the cruise stage was three-axis stabilized with four hydrazine monopropellant reaction engine modules, each including a 22-newton trajectory correction maneuver thruster for propulsion and a 4-newton reaction control system thruster for attitude control (orientation). Orientation of the spacecraft was performed using redundant Sun sensors, star trackers, and inertial measurement units.[7]

During descent, the lander used three clusters of pulse modulated engines, each containing four 266-newton hydrazine monopropellant thrusters. Altitude during landing was measured by a doppler radar system, and an attitude and articulation control subsystem (AACS) controlled the attitude to ensure the spacecraft landed at the optimal azimuth to maximize solar collection and telecommunication with the lander.[4][7][8]

The lander was launched with two hydrazine tanks containing 64 kilograms of propellant and pressurized using helium. Each spherical tank was located at the underside of the lander and provided propellant during the cruise and descent stages.[4][7][8]

Communications edit

During the cruise stage, communications with the spacecraft were conducted over the X band using a medium-gain, horn-shaped antenna and redundant solid state power amplifiers. For contingency measures, a low-gain omni-directional antenna was also included.[4]

The lander was originally intended to communicate data through the failed Mars Climate Orbiter via the UHF antenna. With the orbiter lost on September 23, 1999, the lander would still be able to communicate directly to the Deep Space Network through the Direct-To-Earth (DTE) link, an X band, steerable, medium-gain, parabolic antenna located on the deck. Alternatively, Mars Global Surveyor could be used as a relay using the UHF antenna at multiple times each Martian day. However the Deep Space Network could only receive data from, and not send commands to, the lander using this method. The direct-to-Earth medium-gain antenna provided a 12.6-kbit/s return channel, and the UHF relay path provided a 128-kbit/s return channel. Communications with the spacecraft would be limited to one-hour events, constrained by heat-buildup that would occur in the amplifiers. The number of communication events would also be constrained by power limitations.[4][6][7][8]

Power edit

The cruise stage included two gallium arsenide solar arrays to power the radio system and maintain power to the batteries in the lander, which kept certain electronics warm.[4][7]

After descending to the surface, the lander was to deploy two 3.6-meter-wide gallium arsenide solar arrays, located on either side of the spacecraft. Another two auxiliary solar arrays were located on the side to provide additional power for a total of an expected 200 watts and approximately eight to nine hours of operating time per day.[4][7]

While the Sun would not have set below the horizon during the primary mission, too little light would have reached the solar arrays to remain warm enough for certain electronics to continue functioning. To avoid this problem, a 16-amp-hour nickel hydrogen battery was included to be recharged during the day and to power the heater for the thermal enclosure at night. This solution also was expected to limit the life of the lander. As the Martian days would grow colder in late summer, too little power would be supplied to the heater to avoid freezing, resulting in the battery also freezing and signaling the end of the operating life for the lander.[4][7][8]

Scientific instruments edit

-

Annotated diagram of the Mars Polar Lander spacecraft

-

The spacecraft in stowed position just prior to encapsulation

-

Testing performed at the Spacecraft Assembly and Encapsulation Facility

-

The Mars Polar Lander entry capsule, just prior to being mounted to the Star 48 upper stage

- Mars Descent Imager (MARDI)

- Mounted to the bottom of the lander, the camera was intended to capture 30 images as the spacecraft descended to the surface. The images acquired would be used to provide geographic and geologic context to the landing area.[9]

- Surface Stereo Imager (SSI)

- Using a pair of charge coupled devices (CCD), the stereo panoramic camera was mounted to a one-meter-tall mast and would aid in the thermal evolved gas analyzer in determining areas of interest for the robotic arm. In addition, the camera would be used to estimate the column density of atmospheric dust, the optical depth of aerosols, and slant column abundances of water vapor using narrow-band imaging of the Sun.[10]

- Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR)

- The laser sounding instrument was intended to detect and characterize aerosols in the atmosphere up to three kilometers above the lander. The instrument operated in two modes: active mode, using an included laser diode, and acoustic mode, using the Sun as the light source for the sensor. In active mode, the laser sounder was to emit 100-nanosecond pulses at a wavelength of 0.88-micrometer into the atmosphere, and then record the duration of time to detect the light scattered by aerosols. The duration of time required for the light to return could then be used to determine the abundance of ice, dust and other aerosols in the region. In acoustic mode, the instrument measures the brightness of the sky as lit by the Sun and records the scattering of light as it passes to the sensor.[11]

- Robotic Arm (RA)

- Located on the front of the lander, the robotic arm was a meter-long aluminum tube with an elbow joint and an articulated scoop attached to the end. The scoop was intended to be used to dig into the soil in the direct vicinity of the lander. The soil could then be analyzed in the scoop with the robotic arm camera or transferred into the thermal evolved gas analyzer.[10]

- Robotic Arm Camera (RAC)

- Located on the robotic arm, the charge coupled camera included two red, two green, and four blue lamps to illuminate soil samples for analysis.[10]

- Meteorological Package (MET)

- Several instruments related to sensing and recording weather patterns, were included in the package. Wind, temperature, pressure, and humidity sensors were located on the robotic arm and two deployable masts: a 1.2-meter main mast, located on top of the lander, and a 0.9-meter secondary submast that would deploy downward to acquire measurements close to the ground.[10]

- Thermal and Evolved Gas Analyzer (TEGA)

- The instrument was intended to measure abundances of water, water ice, adsorbed carbon dioxide, oxygen, and volatile-bearing minerals in surface and subsurface soil samples collected and transferred by the robotic arm. Materials placed onto a grate inside one of the eight ovens, would be heated and vaporized at 1,000 °C. The evolved gas analyzer would then record measurements using a spectrometer and an electrochemical cell. For calibration, an empty oven would also be heated during this process for differential scanning calorimetry. The difference in the energy required to heat each oven would then indicate concentrations of water ice and other minerals containing water or carbon dioxide.[10]

- Mars Microphone

- The microphone was intended to be the first instrument to record sounds on another planet. Primarily composed of a microphone generally used with hearing aids, the instrument was expected to record sounds of blowing dust, electrical discharges and the sounds of the operating spacecraft in either 2.6-second or 10.6-second, 12-bit samples.[12] The microphone was built using off-the-shelf parts including a Sensory, Inc. RSC-164 integrated circuit typically used in speech-recognition devices.[13]

Mission profile edit

| Timeline of observations | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Launch and trajectory edit

Mars Polar Lander was launched on January 3, 1999, at 20:21:10 UTC by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration from Space Launch Complex 17B at the Cape Canaveral Air Force Station in Florida, aboard a Delta II 7425–9.5 launch vehicle. The complete burn sequence lasted for 47.7 minutes after a Thiokol Star 48B solid-fuel third stage booster placed the spacecraft into an 11-month, Mars transfer trajectory at a final velocity of 6.884 kilometers per second with respect to Mars. During cruise, the spacecraft was stowed inside an aeroshell capsule and a segment known as the cruise stage provided power and communications with Earth.[4][6][7]

Landing zone edit

The target landing zone was a region near the south pole of Mars, called Ultimi Scopuli, because it featured a large number of scopuli (lobate or irregular scarps).[citation needed]

Landing attempt edit

On December 3, 1999, Mars Polar Lander arrived at Mars and mission operators began preparations for landing. At 14:39:00 UTC, the cruise stage was jettisoned, which began a planned communication dropout to last until the spacecraft had touched down on the surface. Six minutes prior to atmospheric entry, a programmed 80-second thruster firing turned the spacecraft to the proper entry orientation, with the heat shield positioned to absorb the 1,650 °C heat that would be generated as the descent capsule passed through the atmosphere.

Traveling at 6.9 kilometers per second, the entry capsule entered the Martian atmosphere at 20:10:00 UTC, and was expected to land in the vicinity of 76°S 195°W / 76°S 195°W in a region known as Planum Australe. Reestablishment of communication was anticipated for 20:39:00 UTC, after landing. However communication was not reestablished, and the lander was declared lost.[4][6][7]

On May 25, 2008, the Phoenix lander arrived at Mars, and has subsequently completed most of the objectives of the Mars Polar Lander, carrying several of the same or derivative instruments.

Legend: Active (white lined, ※) • Inactive • Planned (dash lined, ⁂)

Intended operations edit

Traveling at approximately 6.9 kilometers/second and 125 kilometers above the surface, the spacecraft entered the atmosphere and was initially decelerated by using a 2.4 meter ablation heat shield, located on the bottom of the entry body, to aerobrake through 116 kilometers of the atmosphere. Three minutes after entry, the spacecraft had slowed to 496 meters per second signaling an 8.4-meter, polyester parachute to deploy from a mortar followed immediately by heat shield separation and MARDI powering on, while 8.8 kilometers above the surface. The parachute further slowed the speed of the spacecraft to 85 meters per second when the ground radar began tracking surface features to detect the best possible landing location.

When the spacecraft had slowed to 80 meters per second, one minute after parachute deployment, the lander separated from the backshell and began a powered descent while 1.3 kilometers aloft. The powered descent was expected to have lasted approximately one minute, bringing the spacecraft 12 meters above the surface. The engines were then shut off and the spacecraft would expectedly fall to the surface and land at 20:15:00 UTC near 76°S 195°W in Planum Australe.[4][6][7][8]

Lander operations were to begin five minutes after touchdown, first unfolding the stowed solar arrays, followed by orienting the medium-gain, direct-to-Earth antenna to allow for the first communication with the Deep Space Network. At 20:39 UTC, a 45-minute transmission was to be broadcast to Earth, transmitting the expected 30 landing images acquired by MARDI and signaling a successful landing. The lander would then power down for six hours to allow the batteries to charge. On the following days, the spacecraft instruments would be checked by operators and science experiments were to begin on December 7 and last for at least the following 90 Martian Sols, with the possibility of an extended mission.[4][6][7][8]

Loss of communications edit

On December 3, 1999, at 14:39:00 UTC, the last telemetry from Mars Polar Lander was sent, just prior to cruise stage separation and the subsequent atmospheric entry. No further signals were received from the spacecraft. Attempts were made by Mars Global Surveyor to photograph the area in which the lander was believed to be. An object was visible and believed to be the lander. However, subsequent imaging performed by Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter resulted in the identified object being ruled out. Mars Polar Lander remains lost.[14][15]

The cause of the communication loss is not known. However, the Failure Review Board concluded that the most likely cause of the mishap was a software error that incorrectly identified vibrations, caused by the deployment of the stowed legs, as surface touchdown.[16] The resulting action by the spacecraft was the shutdown of the descent engines, while still likely 40 meters above the surface. Although it was known that leg deployment could create the false indication, the software's design instructions did not account for that eventuality.[17]

In addition to the premature shutdown of the descent engines, the Failure Review Board also assessed other potential modes of failure.[2] Lacking substantial evidence for the mode of failure, the following possibilities could not be excluded:

- surface conditions exceed landing design capabilities;

- loss of control due to dynamic effects;

- landing site not survivable;

- backshell/parachute contacts lander;

- loss of control due to center-of-mass offset; or

- heatshield fails due to micrometeoroid impact.

The failure of the Mars Polar Lander took place two and a half months after the loss of the Mars Climate Orbiter. Inadequate funding and poor management have been cited as underlying causes of the failures.[18] According to Thomas Young, chairman of the Mars Program Independent Assessment Team, the program "was under funded by at least 30%."[19]

| Quoted from the report[2] |

|---|

|

"A magnetic sensor is provided in each of the three landing legs to sense touchdown when the lander contacts the surface, initiating the shutdown of the descent engines. Data from MPL engineering development unit deployment tests, MPL flight unit deployment tests, and Mars 2001 deployment tests showed that a spurious touchdown indication occurs in the Hall Effect touchdown sensor during landing leg deployment (while the lander is connected to the parachute). The software logic accepts this transient signal as a valid touchdown event if it persists for two consecutive readings of the sensor. The tests showed that most of the transient signals at leg deployment are indeed long enough to be accepted as valid events, therefore, it is almost a certainty that at least one of the three would have generated a spurious touchdown indication that the software accepted as valid. The software—intended to ignore touchdown indications prior to the enabling of the touchdown sensing logic—was not properly implemented, and the spurious touchdown indication was retained. The touchdown sensing logic is enabled at 40 meters altitude, and the software would have issued a descent engine thrust termination at this time in response to a (spurious) touchdown indication. At 40 meters altitude, the lander has a velocity of approximately 13 meters per second, which, in the absence of thrust, is accelerated by Mars gravity to a surface impact velocity of approximately 22 meters per second (the nominal touchdown velocity is 2.4 meters per second). At this impact velocity, the lander could not have survived." |

Aftermath edit

Despite the Mars Polar Lander's failure, Planum Australe, which served as the exploration target for the lander and the two Deep Space 2 probes,[20] would in later years be explored by European Space Agency's MARSIS radar, which examined and analyzed the site from Mars' orbit.[21][22][23][24]

See also edit

- Mars Surveyor 2001 Lander, similar design lander, mission cancelled. Lander used for Phoenix.

- Phoenix lander, 2008

- Exploration of Mars

- ExoMars rover

- List of missions to Mars

- Mars Science Laboratory rover

References edit

- ^ "Mars Polar Lander". NASA Space Science Data Coordinated Archive. Retrieved 2022-12-01.

- ^ a b c "Report on the Loss of the Mars Polar Lander and Deep Space 2 Missions" (PDF). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. March 22, 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-03-16.

- ^ a b "Mars Polar Lander Mission Costs". The Associated Press. December 8, 1999. Retrieved 2020-09-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "1998 Mars Missions Press Kit" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-04-30. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- ^ Huh, Ben (March 3, 1998). "Kids' Names Going To Mars". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on 2013-12-02. Retrieved 2013-05-30.

- ^ a b c d e f "Mars Polar Lander/Deep Space 2 Press Kit" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-12-23. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Mars Polar Lander". NASA/National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- ^ a b c d e f g "MPL: Lander Flight System Description". NASA / JPL. 1998. Archived from the original on 2011-07-21. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- ^ "Mars Descent Imager (MARDI)". NASA/National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- ^ a b c d e "Mars Volatiles and Climate Surveyor (MVACS)". NASA/National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- ^ "Light Detection and Ranging (LIDAR)". NASA/National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- ^ "Mars Microphone". NASA/National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- ^ "Projects: Planetary Microphones -- The Mars Microphone". The Planetary Society. Archived from the original on 2006-08-18.

- ^ "Mars Polar Lander Found at Last?". Sky and Telescope. May 6, 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-07-23. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ^ "Release No. MOC2-1253: Mars Polar Lander NOT Found". Mars Global Surveyor / Mars Orbiter Camera. NASA/JPL/Malin Space Science Systems. October 17, 2005. Archived from the original on 2008-12-07. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ^ NASA 3: Mission Failures. Youtube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21.

- ^ Nancy G. Leveson. The Role of Software in Recent Aerospace Accidents (PDF) (Report).

- ^ Thomas Young (March 14, 2000). Mars Program Independent Assessment Team Summary Report (Report). Draft #7 3/13/00. House Science and Technology Committee. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ^ Jeffrey Kaye (April 14, 2000). "NASA in the Hot Seat". NewsHour with Jim Lehrer. PBS. Archived from the original (transcript) on 2013-12-26. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- ^ Evans, Ben (2019). "'Could Not Have Survived': 20 Years Since NASA's Ill-Fated Mars Polar Lander". AmericaSpace. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- ^ Orosei, R.; et al. (July 25, 2018). "Radar evidence of subglacial liquid water on Mars". Science. 361 (6401): 490–493. arXiv:2004.04587. Bibcode:2018Sci...361..490O. doi:10.1126/science.aar7268. hdl:11573/1148029. PMID 30045881.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth; Overbye, Dennis (July 25, 2018). "A Watery Lake Is Detected on Mars, Raising the Potential for Alien Life – The discovery suggests that watery conditions beneath the icy southern polar cap may have provided one of the critical building blocks for life on the red planet". The New York Times. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- ^ "Huge reservoir of liquid water detected under the surface of Mars". EurekAlert. July 25, 2018. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

- ^ "Liquid water 'lake' revealed on Mars". BBC News. July 25, 2018. Retrieved 2022-04-15.

Further reading edit

- "Mars Polar Lander (1999-001A)". NSSDC Master Catalog. NASA. 2001. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

- Michael C. Malin (July 2005). "Hidden in Plain Sight: Finding Martian Landers". Sky and Telescope. 110 (7): 42–46. Bibcode:2005S&T...110a..42M. ISSN 0037-6604.

- "Press Kit: 1998 Mars Missions" (.PDF) (Press release). National Aeronautics and Space Administration. December 8, 1998. Retrieved 2009-04-22.

External links edit

- Mars Polar Lander site at Jet Propulsion Laboratory

- Mars Polar Lander Mission at The NASA Solar System Exploration Home Page

- Report of the Loss of the Mars Polar Lander and Deep Space 2 Missions