Lonnie Smith (July 3, 1942 – September 28, 2021), styled Dr. Lonnie Smith, was an American jazz Hammond B3 organist who was a member of the George Benson quartet in the 1960s. He recorded albums with saxophonist Lou Donaldson for Blue Note before being signed as a solo act. He owned the label Pilgrimage, and was named the year's best organist by the Jazz Journalists Association nine times.

Lonnie Smith | |

|---|---|

| |

| Background information | |

| Born | July 3, 1942 Lackawanna, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 28, 2021 (aged 79) Fort Lauderdale, Florida, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) | Musician |

| Instrument(s) | Organ |

| Years active | 1960–2021 |

| Labels | |

| Website | drlonniesmith |

Early life edit

Smith was born in Lackawanna, New York, on July 3, 1942.[1] He was raised by his mother and stepfather,[2] and the family had a vocal group and radio program. He stated that his mother was a major influence on him musically, as she introduced him to gospel, classical, and jazz music.[3]

Career edit

Smith was part of several vocal ensembles in the 1950s, including the Teen Kings which included Grover Washington Jr., on sax and his brother Daryl on drums.[4] Art Kubera, the owner of a local music store, gave Smith his first organ, a Hammond B3.[5]

George Benson Quartet edit

Smith's affinity for R&B mixed with his own personal style as he became active in the local music scene. He moved to New York City in 1965,[6] where he met George Benson, the guitarist for Jack McDuff's band. Benson and Smith connected on a personal level, and the two formed the George Benson Quartet, featuring Lonnie Smith, in 1966.[7][8]

Solo career; Finger Lickin' Good edit

After two albums under Benson's leadership, It's Uptown and Cookbook, Smith recorded his first solo album (Finger Lickin' Good Soul Organ) in 1967,[9] with George Benson and Melvin Sparks on guitar, Ronnie Cuber on baritone sax, and Marion Booker on drums. This combination remained stable for the next five years.[7]

After recording several albums with Benson, Smith became a solo recording artist and subsequently recorded over 30 albums under his own name. Numerous prominent jazz artists joined Smith on his albums and in his live performances, including Lee Morgan, David "Fathead" Newman, King Curtis, Terry Bradds, Blue Mitchell, Joey DeFrancesco and Joe Lovano.[5]

Blue Note Records edit

In 1967, Smith met Lou Donaldson, who put him in contact with Blue Note Records. Donaldson asked the quartet to record an album for Blue Note, Alligator Bogaloo, which was recorded in April 1967.[10] Blue Note signed Smith in 1968, and he released five albums on the label,[11] including Think! (with Lee Morgan, David Newman, Melvin Sparks and Marion Booker)[7] and Turning Point (with Lee Morgan, Bennie Maupin, Melvin Sparks and Idris Muhammad).[12]

Smith's next album Move Your Hand was recorded at the Club Harlem in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in August 1969.[13] The album's reception allowed his reputation to grow beyond the Northeast. He recorded another studio album, Drives, and another live album (unreleased at the time),[7] Live at Club Mozambique (recorded in Detroit on May 21, 1970),[14] before leaving Blue Note.[7]

Smith recorded one album in 1971 for Creed Taylor's CTI label,[7] which had already signed George Benson. After a break from recording, he then spent most of the mid-1970s with producer Sonny Lester and his Groove Merchant label,[15][16] then with Lester's LRC labels.[17] It resulted in four albums, with the music output veering between jazz, soul, funk, fusion and even the odd disco-styled track.[18]

Smith rejoined the Blue Note label in March 2015. He released his first Blue Note album in 45 years titled Evolution which was released January 29, 2016, featuring special guests: Robert Glasper and Joe Lovano.[19] His second Blue Note album All in My Mind was recorded live at "The Jazz Standard" in NYC (celebrating his 75th birthday with his longtime musical associates: guitarist Jonathan Kreisberg and drummer Johnathan Blake), and released January 12, 2018.[20] His third Blue Note album, Breathe was also recorded live and released March 26, 2021. It features Iggy Pop on two studio vocal tracks, "Why Can't We Live Together" and "Sunshine Superman".

Tours and performances edit

Smith toured the northeastern United States heavily during the 1970s. He concentrated largely on smaller neighborhood venues during this period. His sidemen included Donald Hahn on trumpet, Ronnie Cuber,[7] Dave Hubbard,[21] Bill Easley and George Adams on saxes,[22][23] George Benson,[7] Perry Hughes,[24] Marc Silver,[25] Billy Rogers and Larry McGee on guitars,[26][27] and Joe Dukes,[28] Sylvester Goshay,[27] Phillip Terrell,[29] Marion Booker,[7] Jimmy Lovelace,[30] Charles Crosby,[31][32] Art Gore,[33] Norman Connors,[34] and Bobby Durham on drums.[35]

Smith performed at several prominent jazz festivals with artists including Grover Washington Jr., Ron Carter, Dizzy Gillespie, Lou Donaldson, Ron Holloway, and Santana. He also played with musicians outside of jazz, such as Dionne Warwick, Gladys Knight,[36] and Etta James.[37]

Personal life edit

Smith had five children: Lani, Chandra, Charisse, Lonnie, and Vonnie.[2]

Smith died of pulmonary fibrosis on September 28, 2021, in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, at the age of 79.[2][15]

Public image edit

Starting in the 1970s, Smith added the "Dr." title to his name.[7] The origin of the moniker is unclear and was not an academic title. One theory is that fellow musicians called Smith this due to his ability to "doctor up" their music.[38] Another is that he adopted the title in an attempt to differentiate himself from other musicians.[39] Smith himself gave the following explanation:

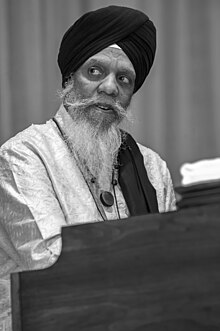

But I’m a doctor of music. I’ve been playing long enough to operate on it, and I do have a degree, and I will operate on you. I’m a neurosurgeon. If you need something done to you, I can do it. But when I go up on that stand, the only thing I’m thinking of is music. I’m thinking to touch you with that music. I don’t think about the turban, I don’t think about the doctor — I just think about how I’m going to touch you.[40]

Smith was well known for wearing a turban.[7][40] He stated that the turban had no religious significance and was something he had worn since he was young.[2][38] Matt Collar of AllMusic suggested the turban was a theatrical gesture to his spiritual views on music,[7] but Smith himself said he did not know why he started wearing a turban and referenced the iconic headwear of Sun Ra and Sonny Rollins' mohawk.[38][40]

Awards and honors edit

- Organ Keyboardist of the Year, Jazz Journalist Association, 2003–2005, 2008–2011, 2013, 2014[1]

- NEA Jazz Master, 2017[2][8]

Discography edit

As leader edit

- Finger Lickin' Good Soul Organ (Columbia, 1967)[18]

- Think! (Blue Note, 1968)[18]

- Turning Point (Blue Note, 1969)[18]

- Move Your Hand (Blue Note, 1969)[18]

- Drives (Blue Note, 1970)[18]

- Mama Wailer (Kudu, 1971)[18]

- Afro–desia (Groove Merchant, 1975)[18]

- Keep on Lovin' (Groove Merchant, 1976)[18]

- Funk Reaction (LRC [Lester Radio Corporation], 1977)[18]

- Gotcha (LRC [Lester Radio Corporation], 1978)[18]

- Lonnie Smith (America, 1979)[18]

- When the Night Is Right! (Chiaroscuro, 1980)[18]

- Lenox and Seventh (Black & Blue, 1985) – with Alvin Queen[41]

- Afro Blue: Tribute To John Coltrane (Venus; MusicMasters/BMG, 1993)[18]

- Foxy Lady: Tribute to Jimi Hendrix (Venus; MusicMasters/BMG, 1994)[18]

- Purple Haze: Tribute to Jimi Hendrix (Venus; MusicMasters/BMG, 1994)[18]

- Live at Club Mozambique (Blue Note, 1995) – recorded in 1970[18]

- The Turbanator (32 Jazz, 2000) – recorded in 1991 with Jimmy Ponder[18]

- Boogaloo to Beck: A Tribute (Scufflin', 2003)[18]

- Too Damn Hot! (Palmetto, 2004)[18]

- Jungle Soul (Palmetto, 2006)[18]

- Rise Up! (Palmetto, 2008)[18]

- The Art of Organizing (Criss Cross, 2009) – recorded in 1993[18]

- Spiral (Palmetto, 2010)[18]

- The Healer [live] (Pilgrimage, 2012)[18]

- In the Beginning (Pilgrimage, 2013) [2CD][18]

- Evolution (Blue Note, 2016)[18]

- All in My Mind (Blue Note, 2018)[18]

- Breathe (Blue Note, 2021)[18]

As sideman edit

|

With Eric Allison With George Benson

With Lou Donaldson

With Richie Hart With Red Holloway With Javon Jackson

With Jimmy McGriff

With Jimmy Ponder

|

With others

|

References edit

- ^ a b Gilbreath, Mikayla (January 7, 2008). "Dr. Lonnie Smith: Organ Guru". All About Jazz. Retrieved January 21, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e Keepnews, Peter (September 29, 2021). "Lonnie Smith, Soulful Jazz Organist, Is Dead at 79". The New York Times. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Manheim, James M. (2005). "Dr. Lonnie Smith". Contemporary Black Biography. Vol. 49. Detroit: Gale. pp. 133–135. ISBN 978-1-4144-0548-3. ISSN 1058-1316. OCLC 728680730.

- ^ Bennett, Bill (January/February 2005) "Dr Lonnie Smith - The Doctor Is In". JazzTimes.

- ^ a b Feather, Leonard; Gitler, Ira (2007). The Biographical Encyclopedia of Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 612. ISBN 978-0-19-532000-8.

- ^ Blake, Daniel (January 13, 2015). "Smith, "Dr." Lonnie". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.a2276518. ISBN 9781561592630.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Collar, Matt. "Dr. Lonnie Smith – Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ a b "Dr. Lonnie Smith". National Endowment for the Arts. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Farberman, Brad (March 24, 2021). "How Lonnie Smith Found an Unlikely New Collaborator: Iggy Pop". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Cook, Richard (2003). Blue Note Records: The Biography. Justin, Charles & Co. pp. 191–192. ISBN 1-932112-10-3. OCLC 52092736.

- ^ Minsker, Evan (September 29, 2021). "Dr. Lonnie Smith, Hammond Organ Virtuoso, Dies at 79". Pitchfork. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Turning Point – Dr. Lonnie Smith". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Lord, Tom (1999). The Jazz Discography. Vol. 21. Lord Music Reference. p. 929. ISBN 1-881993-00-0. OCLC 30547554.

- ^ Unterberger, Richie. "Live at Club Mozambique – Dr. Lonnie Smith". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Bryant, Greg (September 28, 2021). "Dr. Lonnie Smith, Master Of The Hammond Organ, Dies At 79". NPR. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Brandle, Lars (September 29, 2021). "Dr. Lonnie Smith, Legendary Hammond Organist and Jazz Master, Dies at 79". Billboard. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "The Best of Today's Jazz on Marlin Records". Billboard. Vol. 89, no. 47. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. November 26, 1977. p. 65. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac "Dr. Lonnie Smith – Album Discography". AllMusic. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ Collar, Matt. "Evolution – Dr. Lonnie Smith". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Jurek, Thom. "All in My Mind – Dr. Lonnie Smith". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Dave Hubbard – Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Kunz Goldman, Mary (August 7, 2000). "A Rainy Reunion". The Buffalo News. Archived from the original on September 30, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Jazz Journal International. Vol. 61. Billboard Limited. 2008. p. 30.

- ^ Doster, Eve (April 27, 2005). "Night and Day". Detroit Metro Times. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Contemporary Guitar Improvisation Master Class". Sweetwater Sound. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Stewart, Zan (September 25, 2008). "Drummer's dynamism drives band". The Star-Ledger. Advance Publications. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Move Your Hand – Dr. Lonnie Smith". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Joe Dukes – Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Down Beat. Vol. 33. Maher Publications. 1966.

- ^ Silbergleit, Paul (November 1, 2015). 25 Great Jazz Guitar Solos: Transcriptions, Lessons, Bios, Photos. Hal Leonard Corporation. p. 74. ISBN 9781495055416.

- ^ Jurek, Thom. "Here Comes the Whistleman – Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Roland Kirk". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Out to Lunch playlist for 10/20/2011". WKCR-FM. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Art Gore". Yamaha Corporation. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Down Beat. Vol. 43. Maher Publications. 1976.

- ^ "Legends of Acid Jazz – Red Holloway: Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Fawcett, Thomas (September 29, 2017). "Dr. Lonnie Smith's B-3 Love Affair". The Austin Chronicle. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ Legaspi, Althea (September 29, 2021). "Dr. Lonnie Smith, Lauded Hammond Organist, Dead at 79". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c Milkowski, Bill (September 29, 2021). "Dr. Lonnie Smith: The Doctor Is In!". JazzTimes. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Organ Maestro Dr. Lonnie Smith Has Died At Age 79". Music Feeds. September 29, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Dr. Lonnie Smith: 1942–2021". downbeat.com. September 29, 2021. Retrieved September 30, 2021.

- ^ "Lonnie Smith / Alvin Queen – Lenox and Seventh". Jazz Music Archives. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa "Dr. Lonnie Smith – Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved September 29, 2021.

- ^ "Remembering Wes". AllMusic. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ "Greasy Street". AllMusic. Retrieved January 12, 2018.

- ^ "Reviews – Jazz/Fusion". Billboard. Vol. 97, no. 45. Nielsen Business Media, Inc. November 9, 1985. p. 79. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Lord, Tom (1997). The Jazz Discography. Vol. 17. Lord Music Reference. p. 571. ISBN 9781881993025.

External links edit

- Lonnie Smith Interview at NAMM Oral History Library

- Dr. Lonnie Smith discography at Discogs

- Dr. Lonnie Smith at IMDb