In mathematics, extrapolation is a type of estimation, beyond the original observation range, of the value of a variable on the basis of its relationship with another variable. It is similar to interpolation, which produces estimates between known observations, but extrapolation is subject to greater uncertainty and a higher risk of producing meaningless results. Extrapolation may also mean extension of a method, assuming similar methods will be applicable. Extrapolation may also apply to human experience to project, extend, or expand known experience into an area not known or previously experienced so as to arrive at a (usually conjectural) knowledge of the unknown[1] (e.g. a driver extrapolates road conditions beyond his sight while driving). The extrapolation method can be applied in the interior reconstruction problem.

Method edit

A sound choice of which extrapolation method to apply relies on a prior knowledge of the process that created the existing data points. Some experts have proposed the use of causal forces in the evaluation of extrapolation methods.[2] Crucial questions are, for example, if the data can be assumed to be continuous, smooth, possibly periodic, etc.

Linear edit

Linear extrapolation means creating a tangent line at the end of the known data and extending it beyond that limit. Linear extrapolation will only provide good results when used to extend the graph of an approximately linear function or not too far beyond the known data.

If the two data points nearest the point to be extrapolated are and , linear extrapolation gives the function:

(which is identical to linear interpolation if ). It is possible to include more than two points, and averaging the slope of the linear interpolant, by regression-like techniques, on the data points chosen to be included. This is similar to linear prediction.

Polynomial edit

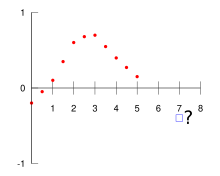

A polynomial curve can be created through the entire known data or just near the end (two points for linear extrapolation, three points for quadratic extrapolation, etc.). The resulting curve can then be extended beyond the end of the known data. Polynomial extrapolation is typically done by means of Lagrange interpolation or using Newton's method of finite differences to create a Newton series that fits the data. The resulting polynomial may be used to extrapolate the data.

High-order polynomial extrapolation must be used with due care. For the example data set and problem in the figure above, anything above order 1 (linear extrapolation) will possibly yield unusable values; an error estimate of the extrapolated value will grow with the degree of the polynomial extrapolation. This is related to Runge's phenomenon.

Conic edit

A conic section can be created using five points near the end of the known data. If the conic section created is an ellipse or circle, when extrapolated it will loop back and rejoin itself. An extrapolated parabola or hyperbola will not rejoin itself, but may curve back relative to the X-axis. This type of extrapolation could be done with a conic sections template (on paper) or with a computer.

French curve edit

French curve extrapolation is a method suitable for any distribution that has a tendency to be exponential, but with accelerating or decelerating factors.[3] This method has been used successfully in providing forecast projections of the growth of HIV/AIDS in the UK since 1987 and variant CJD in the UK for a number of years. Another study has shown that extrapolation can produce the same quality of forecasting results as more complex forecasting strategies.[4]

Geometric Extrapolation with error prediction edit

Can be created with 3 points of a sequence and the "moment" or "index", this type of extrapolation have 100% accuracy in predictions in a big percentage of known series database (OEIS).[5]

Example of extrapolation with error prediction :

Quality edit

Typically, the quality of a particular method of extrapolation is limited by the assumptions about the function made by the method. If the method assumes the data are smooth, then a non-smooth function will be poorly extrapolated.

In terms of complex time series, some experts have discovered that extrapolation is more accurate when performed through the decomposition of causal forces.[6]

Even for proper assumptions about the function, the extrapolation can diverge severely from the function. The classic example is truncated power series representations of sin(x) and related trigonometric functions. For instance, taking only data from near the x = 0, we may estimate that the function behaves as sin(x) ~ x. In the neighborhood of x = 0, this is an excellent estimate. Away from x = 0 however, the extrapolation moves arbitrarily away from the x-axis while sin(x) remains in the interval [−1, 1]. I.e., the error increases without bound.

Taking more terms in the power series of sin(x) around x = 0 will produce better agreement over a larger interval near x = 0, but will produce extrapolations that eventually diverge away from the x-axis even faster than the linear approximation.

This divergence is a specific property of extrapolation methods and is only circumvented when the functional forms assumed by the extrapolation method (inadvertently or intentionally due to additional information) accurately represent the nature of the function being extrapolated. For particular problems, this additional information may be available, but in the general case, it is impossible to satisfy all possible function behaviors with a workably small set of potential behavior.

In the complex plane edit

In complex analysis, a problem of extrapolation may be converted into an interpolation problem by the change of variable . This transform exchanges the part of the complex plane inside the unit circle with the part of the complex plane outside of the unit circle. In particular, the compactification point at infinity is mapped to the origin and vice versa. Care must be taken with this transform however, since the original function may have had "features", for example poles and other singularities, at infinity that were not evident from the sampled data.

Another problem of extrapolation is loosely related to the problem of analytic continuation, where (typically) a power series representation of a function is expanded at one of its points of convergence to produce a power series with a larger radius of convergence. In effect, a set of data from a small region is used to extrapolate a function onto a larger region.

Again, analytic continuation can be thwarted by function features that were not evident from the initial data.

Also, one may use sequence transformations like Padé approximants and Levin-type sequence transformations as extrapolation methods that lead to a summation of power series that are divergent outside the original radius of convergence. In this case, one often obtains rational approximants.

Fast edit

The extrapolated data often convolute to a kernel function. After data is extrapolated, the size of data is increased N times, here N is approximately 2–3. If this data needs to be convoluted to a known kernel function, the numerical calculations will increase N log(N) times even with fast Fourier transform (FFT). There exists an algorithm, it analytically calculates the contribution from the part of the extrapolated data. The calculation time can be omitted compared with the original convolution calculation. Hence with this algorithm the calculations of a convolution using the extrapolated data is nearly not increased. This is referred as the fast extrapolation. The fast extrapolation has been applied to CT image reconstruction.[7]

Extrapolation arguments edit

Extrapolation arguments are informal and unquantified arguments which assert that something is probably true beyond the range of values for which it is known to be true. For example, we believe in the reality of what we see through magnifying glasses because it agrees with what we see with the naked eye but extends beyond it; we believe in what we see through light microscopes because it agrees with what we see through magnifying glasses but extends beyond it; and similarly for electron microscopes. Such arguments are widely used in biology in extrapolating from animal studies to humans and from pilot studies to a broader population.[8]

Like slippery slope arguments, extrapolation arguments may be strong or weak depending on such factors as how far the extrapolation goes beyond the known range.[9]

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ Extrapolation, entry at Merriam–Webster

- ^ J. Scott Armstrong; Fred Collopy (1993). "Causal Forces: Structuring Knowledge for Time-series Extrapolation". Journal of Forecasting. 12 (2): 103–115. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.42.40. doi:10.1002/for.3980120205. S2CID 3233162. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ AIDSCJDUK.info Main Index

- ^ J. Scott Armstrong (1984). "Forecasting by Extrapolation: Conclusions from Twenty-Five Years of Research". Interfaces. 14 (6): 52–66. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.715.6481. doi:10.1287/inte.14.6.52. S2CID 5805521. Retrieved 2012-01-10.

- ^ V. Nos (2021). "Probnet: Geometric Extrapolation of Integer Sequences with error prediction". Retrieved 2023-03-14.

- ^ J. Scott Armstrong; Fred Collopy; J. Thomas Yokum (2004). "Decomposition by Causal Forces: A Procedure for Forecasting Complex Time Series". International Journal of Forecasting. 21: 25–36. doi:10.1016/j.ijforecast.2004.05.001. S2CID 8816023.

- ^ Shuangren Zhao; Kang Yang; Xintie Yang (2011). "Reconstruction from truncated projections using mixed extrapolations of exponential and quadratic functions" (PDF). Journal of X-Ray Science and Technology. 19 (2): 155–72. doi:10.3233/XST-2011-0284. PMID 21606580. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-09-29. Retrieved 2014-06-03.

- ^ Steel, Daniel (2007). Across the Boundaries: Extrapolation in Biology and Social Science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195331448.

- ^ Franklin, James (2013). "Arguments whose strength depends on continuous variation". Informal Logic. 33 (1): 33–56. doi:10.22329/il.v33i1.3610. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

References edit

- Extrapolation Methods. Theory and Practice by C. Brezinski and M. Redivo Zaglia, North-Holland, 1991.

- Avram Sidi: "Practical Extrapolation Methods: Theory and Applications", Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-66159-5 (2003).

- Claude Brezinski and Michela Redivo-Zaglia : "Extrapolation and Rational Approximation", Springer Nature, Switzerland, ISBN 9783030584177, (2020).