The Eurasian hoopoe (Upupa epops) is the most widespread species of the genus Upupa. It is a distinctive cinnamon coloured bird with black and white wings, a tall erectile crest, a broad white band across a black tail, and a long narrow downcurved bill. Its call is a soft "oop-oop-oop".

| Eurasian hoopoe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Individual in Almora, Uttarakhand, India with a raised crown | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Bucerotiformes |

| Family: | Upupidae |

| Genus: | Upupa |

| Species: | U. epops

|

| Binomial name | |

| Upupa epops | |

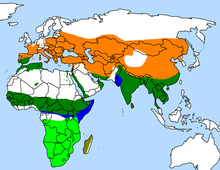

Eurasian hoopoe (breeding)

Eurasian hoopoe (resident)

Eurasian hoopoe (wintering)

Madagascar hoopoe

African hoopoe

The Eurasian hoopoe is native to Europe, Asia and the northern half of Africa. It is migratory in the northern part of its range. Some ornithologists consider the African and Madagascar hoopoes its subspecies. In 2008, the Eurasian hoopoe was elected as the national bird of Israel.[2]

Taxonomy edit

The Eurasian hoopoe was formally described in 1758 by the Swedish naturalist Carl Linnaeus in the tenth edition of his Systema Naturae.[3] He cited the earlier descriptions by the French naturalist Pierre Belon and by the Swiss naturalist Conrad Gessner, both of which had been published in 1555.[4][5] Linnaeus placed the Eurasian hoopoe with the northern bald ibis and the red-billed chough in the genus Upupa and coined the binomial name Upupa epops.[3] The specific epithet epops in the Ancient Greek word for a hoopoe.[6]

Subspecies edit

Six subspecies of the Eurasian hoopoe are recognised in the list of world birds maintained by Frank Gill, Pamela Rasmussen and David Donsker on behalf of the International Ornithological Committee (IOC).[7] The subspecies vary in size and the depth of colour in the plumage. A further subspecies has been proposed: U. e. orientalis in northwestern India.[8]

| Subspecies[7] | Breeding range[7] | Distinctive features[8] |

|---|---|---|

| U. e. epops Linnaeus, 1758 |

northwest Africa and Europe east to central south Russia, northwest China and northwest India | Nominate |

| U. e. ceylonensis Reichenbach, 1853 |

central, south India and Sri Lanka | Smaller than nominate, more rufous overall, no white in crest |

| U. e. longirostris Jerdon, 1862 |

northeast India to south China, Indochina and north Malay Peninsula | Larger than nominate, pale |

| U. e. major Brehm C.L., 1855 |

Egypt | Larger than nominate, longer billed, narrower tailband, greyer upperparts |

| U. e. senegalensis Swainson, 1837 |

Senegal and Gambia to Somalia | Smaller than nominate, shorter winged |

| U. e. waibeli Reichenow, 1913 |

Cameroon to northwest Kenya and north Uganda | As senegalensis but darker plumage and more white on wings |

Description edit

The Eurasian hoopoe is a medium-sized bird, 25–32 cm (9.8–12.6 in) long, with a 44–48 cm (17–19 in) wingspan. It weighs 46–89 g (1.6–3.1 oz).[8] The species is highly distinctive, with a long, thin tapering bill that is black with a fawn base. The strengthened musculature of the head allows the bill to be opened when probing inside the soil. The hoopoe has broad and rounded wings capable of strong flight; these are larger in the northern migratory subspecies. The hoopoe has a characteristic undulating flight, which is like that of a giant butterfly, caused by the wings half closing at the end of each beat or short sequence of beats.[8] Adults may begin their moult after the breeding season and continue after they have migrated for the winter.[9]

The call is typically a trisyllabic oop-oop-oop, which may give rise to its English and scientific names, although two and four syllables are also common. An alternative explanation of the English and scientific names is that they are derived from the French name for the bird, huppée, which means crested. In the Himalayas, the calls can be confused with that of the Himalayan cuckoo (Cuculus saturatus), although the cuckoo typically produces four notes. Other calls include rasping croaks, when alarmed, and hisses. Females produce a wheezy note during courtship feeding by the male.[10]

Distribution and habitat edit

The Eurasian hoopoe is widespread in Europe, Asia, and North Africa and northern Sub-Saharan Africa.[8] Most European and north Asian birds migrate to the tropics in winter.[11] Those breeding in Europe usually migrate to the Sahel belt of sub-Saharan Africa.[12][13] The birds predominantly migrate at night.[14] In contrast, the African populations are sedentary all year. The species has been a vagrant in Alaska;[15] U. e. saturata was recorded there in 1975 in the Yukon Delta.[16] Hoopoes have been known to breed north of their European range,[17] and in southern England during warm, dry summers that provide plenty of grasshoppers and similar insects,[18] although as of the early 1980s northern European populations were reported to be in the decline, possibly due to changes in climate.[17] In 2015, a record numbers of hoopoes were recorded in Ireland, with at least 50 birds recorded in the southwest of the country.[19] This was the highest recorded number since 1965 when 65 individuals were sighted.[20]

The hoopoe has two basic requirements of its habitat: bare or lightly vegetated ground on which to forage and vertical surfaces with cavities (such as trees, cliffs or even walls, nestboxes, haystacks, and abandoned burrows[17]) in which to nest. These requirements can be provided in a wide range of ecosystems, and as a consequence the hoopoe inhabits a wide range of habitats such as heathland, wooded steppes, savannas and grasslands, as well as forest glades.

Hoopoes make seasonal movements in response to rain in some regions such as in Ceylon and in the Western Ghats.[21] Birds have been seen at high altitudes during migration across the Himalayas. One was recorded at about 6,400 m (21,000 ft) by the first Mount Everest expedition.[10]

Behaviour and ecology edit

In what was long thought to be a defensive posture, hoopoes sunbathe by spreading out their wings and tail low against the ground and tilting their head up; they often fold their wings and preen halfway through.[22] They also enjoy taking dust and sand baths.[23]

Food and feeding edit

The diet of the Eurasian hoopoe is mostly composed of insects, although small reptiles, frogs and plant matter such as seeds and berries are sometimes taken as well. It is a solitary forager which typically feeds on the ground. More rarely they will feed in the air, where their strong and rounded wings make them fast and manoeuvrable, in pursuit of numerous swarming insects. More commonly their foraging style is to stride over relatively open ground and periodically pause to probe the ground with the full length of their bill. Insect larvae, pupae and mole crickets are detected by the bill and either extracted or dug out with the strong feet. Hoopoes will also feed on insects on the surface, probe into piles of leaves, and even use the bill to lever large stones and flake off bark. Common diet items include crickets, locusts, beetles, earwigs, cicadas, ant lions, bugs and ants. These can range from 10 to 150 mm (3⁄8 to 5+7⁄8 in) in length, with a preferred prey size of around 20–30 mm (3⁄4–1+1⁄8 in). Larger prey items are beaten against the ground or a preferred stone to kill them and remove indigestible body parts such as wings and legs.[8]

Breeding edit

The hoopoe genus is monogamous, although the pair bond apparently only lasts for a single season, and territorial. The male calls frequently to advertise his ownership of the territory. Chases and fights between rival males (and sometimes females) are common and can be brutal.[8] Birds will try to stab rivals with their bills, and individuals are occasionally blinded in fights.[24] The nest is in a hole in a tree or wall, and has a narrow entrance.[23] It may be unlined, or various scraps may be collected.[17] The female alone is responsible for incubating the eggs. Clutch size varies with location: Northern Hemisphere birds lay more eggs than those in the Southern Hemisphere, and birds at higher latitudes have larger clutches than those closer to the equator. In central and northern Europe and Asia the clutch size is around 12, whereas it is around four in the tropics and seven in the subtropics. The eggs are round and milky blue when laid, but quickly discolour in the increasingly dirty nest.[8] They weigh 4.5 g (0.16 oz).[22] A replacement clutch is possible.[17]

The incubation period for the species is between 15 and 18 days, during which time the male feeds the female. Incubation begins as soon as the first egg is laid, so the chicks are born asynchronously. The chicks hatch with a covering of downy feathers. By around day three to five, feather quills emerge which will become the adult feathers. The chicks are brooded by the female for between 9 and 14 days.[8] The female later joins the male in the task of bringing food.[23] The young fledge in 26 to 29 days and remain with the parents for about a week more.[17] Hoopoes show hatching asynchrony of eggs which is thought to allow for brood reduction when food availability is low.[25]

Hoopoes have well-developed anti-predator defences in the nest. The uropygial gland of the incubating and brooding female is quickly modified to produce a foul-smelling liquid, and the glands of nestlings do so as well. These secretions are rubbed into the plumage. The secretion, which smells like rotting meat, is thought to help deter predators, as well as deter parasites and possibly act as an antibacterial agent.[26] Recent evidence suggests that the secretions may vary in composition depending on the microbiological composition of the female's uropygial gland; furthermore, the secretions may have an impact on the color of eggs, serving as an indicator of antimicrobial health for the adults during incubation. The secretions stop soon before the young leave the nest.[22] From the age of six days, nestlings can also direct streams of faeces at intruders, and will hiss at them in a snake-like fashion.[8] The young also strike with their bill or with one wing.[22]

Relationship with humans edit

The diet of the Eurasian hoopoe includes many species considered by humans to be pests, such as the pupae of the processionary moth, a damaging forest pest.[27] For this reason the species is afforded protection under the law in many countries.[8]

Hoopoes are distinctive birds and have made a cultural impact over much of their range. They were considered sacred in Ancient Egypt, and were "depicted on the walls of tombs and temples". During the Old Kingdom, the hoopoe was used in the iconography as a symbolic code to indicate the child was the heir and successor of his father.[28] They achieved a similar standing in Minoan Crete.[22]

In the Torah, Leviticus 11:13–19, hoopoes were listed among the animals that are unclean and should not be eaten. They are also listed in Deuteronomy 14:18[29] as not kosher.

The hoopoe also appears in the Quran and is known as the "Hudhud" (هدهد), in Surah Al-Naml 27:20–22: "And he Solomon sought among the birds and said: How is it that I see not the hoopoe, or is he among the absent? (20) I verily will punish him with hard punishment or I verily will slay him, or he verily shall bring me a plain excuse. (21) But he [the hoopoe] was not long in coming, and he said: I have found out (a thing) that thou apprehendest not, and I come unto thee from Sheba with sure tidings."

Hoopoes were seen as a symbol of virtue in Persia. A hoopoe was a leader of the birds in the Persian book of poems The Conference of the Birds ("Mantiq al-Tayr" by Attar) and when the birds seek a king, the hoopoe points out that the Simurgh was the king of the birds.[30]

Hoopoes were thought of as thieves across much of Europe, and harbingers of war in Scandinavia.[31] In Estonian tradition, hoopoes are strongly connected with death and the underworld; their song is believed to foreshadow death for many people or cattle.[32]

The hoopoe is the king of the birds in the Ancient Greek comedy The Birds by Aristophanes. In Ovid's Metamorphoses, book 6, King Tereus of Thrace rapes Philomela, his wife Procne's sister, and cuts out her tongue. In revenge, Procne kills their son Itys and serves him as a stew to his father. When Tereus sees the boy's head, which is served on a platter, he grabs a sword but just as he attempts to kill the sisters, they are turned into birds—Procne into a swallow and Philomela into a nightingale. Tereus himself is turned into an epops (6.674), translated as lapwing by Dryden[33] and lappewincke (lappewinge) by John Gower in his Confessio Amantis,[34] or hoopoe in A. S. Kline's translation.[35] The bird's crest indicates his royal status, and his long, sharp beak is a symbol of his violent nature. English translators and poets probably had the northern lapwing in mind, considering its crest.

The hoopoe was chosen as the national bird of Israel in May 2008 in conjunction with the country's 60th anniversary, following a national survey of 155,000 citizens, outpolling the white-spectacled bulbul.[36][37] The hoopoe appears on the Logo of the University of Johannesburg and is the official mascot of the University's sports. The municipalities of Armstedt and Brechten, Germany, have hoopoes in their coats of arms.

In Morocco, hoopoes are traded live and as medicinal products in the markets, primarily in herbalist shops. This trade is unregulated and a potential threat to local populations[38]

Three CGI enhanced hoopoes, together with other birds collectively named "the tittifers", are often shown whistling a song in the BBC children's television series In the Night Garden....

-

Hoopoe featured in The Sketching of Rare Birds by Emperor Huizong of Song in the 12th century

-

Hoopoe in Israel. The hoopoe is Israel's national bird.

-

The Hoopoe bird was recorded as residing in Britain in the 18th century

Conservation edit

The Eurasian Hoopoe is listed as a species of "Least concern" by the IUCN. Despite the fact, the species has been in a continuous decline according to the organisation since 2008,[39] the causes being loss of habitat and over-hunting.

Hunting is of concern in southern Europe and Asia.[16]

In Europe, the hoopoe seems to have a stable population though it is threatened in several regions. The bird is considered extinct in Sweden[40] and "needing active conservation" in Poland.[41] The species has recovered and stabilised in Switzerland, however they remain vulnerable.[42]

Citations edit

- ^ BirdLife International (2020). "Upupa epops". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22682655A181836360. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22682655A181836360.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ "Caring, but not kosher, national bird for Israel". NBC_News. May 29, 2008. Retrieved November 7, 2023.

- ^ a b Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis (in Latin). Vol. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Stockholm): Laurentii Salvii. p. 117.

- ^ Belon, Pierre (1555). L'histoire de la natvre des oyseavx : avec levrs descriptions, & naïfs portraicts retirez du natvrel, escrite en sept livres (in French). Paris: Gilles Corrozet. p. 293.

- ^ Gesner, Conrad (1555). Historiae animalium liber III qui est de auium natura. Adiecti sunt ab initio indices alphabetici decem super nominibus auium in totidem linguis diuersis: & ante illos enumeratio auium eo ordiné quo in hoc volumine continentur (in Latin). Zurich: Froschauer. p. 743.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 147. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ a b c Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (January 2023). "Mousebirds, Cuckoo Roller, trogons, hoopoes, hornbills". IOC World Bird List Version 13.1. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Krištin, A. (2001). "Family Upupidae (Hoopoes)". In del Hoyo, J.; Elliott, A.; Sargatal, J. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World. Vol. 6: Mousebirds to Hornbills. Barcelona, Spain: Lynx Edicions. pp. 396–411 [410]. ISBN 978-84-87334-30-6.

- ^ RSPB Handbook of British Birds (2014). UK ISBN 978-1-4729-0647-2.

- ^ a b Ali, Sálim; Ripley, S. Dillon (1970). Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan, together with those of Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan and Ceylon. Vol. 4: Frogmouths to Pittas. Bombay, India: Oxford University Press. pp. 124–129.

- ^ Reichlin, T.S.; Schaub, M.; Menz, M.H.M.; Mermod, M.; Portner, P.; Arlettaz, R.; Jenni, L. (2009). "Migration patterns of Hoopoe Upupa epops and Wryneck Jynx torquilla: an analysis of European ring recoveries". Journal of Ornithology. 150 (2): 393–400. doi:10.1007/s10336-008-0361-3. S2CID 43360238.

- ^ Bächler, E.; Hahn, S.; Schaub, M.; Arlettaz, R.; Jenni, L.; Fox, J.W.; Afanasyev, V.; Liechti, F. (2010). "Year-round tracking of small trans-Saharan migrants using light-level geolocators". PLOS ONE. 5 (3): e9566. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9566B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009566. PMC 2832685. PMID 20221266.

- ^ Van Wijk, R.E.; Bauer, S.; Schaub, M. (2016). "Repeatability of individual migration routes, wintering sites, and timing in a long-distance migrant bird". Ecology and Evolution. 6 (24): 8679–8685. doi:10.1002/ece3.2578. PMC 5192954. PMID 28035259.

- ^ Liechti, F.; Bauer, S.; Dhanjal-Adams, K.L.; Emmenegger, T.; Zehtindjiev, P.; Hahn, S. (2018). "Miniaturized multi-sensor loggers provide new insight into year-round flight behaviour of small trans-Sahara avian migrants". Movement Ecology. 6 (1): 19. doi:10.1186/s40462-018-0137-1. PMC 6167888. PMID 30305904.

- ^ Dau, Christian; Paniyak, Jack (1977). "Hoopoe, A First Record for North America" (PDF). Auk. 94 (3): 601.

- ^ a b Heindel, Matthew T. (2006). Jonathan Alderfer (ed.). Complete Birds of North America. National Geographic Society. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-7922-4175-1.

- ^ a b c d e f Pforr, Manfred; Alfred Limbrunner (1982). The Breeding Birds of Europe 2: A Photographic Handbook. London: Croom and Helm. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-7099-2020-5.

- ^ Soper, Tony (1982). Birdwatch. Exeter, England: Webb & Bower. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-906671-55-9.

- ^ Healy, Alison (27 April 2015). "Hoopoe causing a hoopla in southeast as 50 exotic birds spotted". The Irish Times. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- ^ "Hoopoe invasion of Ireland's south coast". Ireland's Wildlife. 2015-04-15. Retrieved 2020-07-27.

- ^ Champion-Jones, RN (1937). "The Ceylon Hoopoe (Upupa epops ceylonensis Reichb.)". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 39 (2): 418.

- ^ a b c d e Fry, Hilary C. (2003). Christopher Perrins (ed.). Firefly Encyclopedia of Birds. Firefly Books. pp. 382. ISBN 978-1-55297-777-4.

- ^ a b c Harrison, C.J.O.; Christopher Perrins (1979). Birds: Their Ways, Their World. The Reader's Digest Association. pp. 303–304. ISBN 978-0-89577-065-3.

- ^ Martín-Vivaldi, Manuel; Palomino, José J.; Soler, Manuel (2004). "Strophe length in spontaneous songs predicts male response to playback in the Hoopoe Upupa epops". Ethology. 110 (5): 351–362. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0310.2004.00971.x.

- ^ Hildebrandt, B.; Schaub, M. (2018). "The effects of hatching asynchrony on growth and mortality patterns in Eurasian Hoopoe Upupa epops nestlings". Ibis. 160 (1): 145–157. doi:10.1111/ibi.12529.

- ^ Martín-Platero, Antonio M.; et al. (2006). "Characterization of antimicrobial substances produced by Enterococcus faecalis MRR 10-3, isolated from the uropygial gland of the Hoopoe (Upupa epops)". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 72 (6): 4245–4249. Bibcode:2006ApEnM..72.4245M. doi:10.1128/AEM.02940-05. PMC 1489579. PMID 16751538.

- ^ Battisti, A; Bernardi, M.; Ghiraldo, C. (2000). "Predation by the hoopoe (Upupa epops) on pupae of Thaumetopoea pityocampa and the likely influence on other natural enemies". Biocontrol. 45 (3): 311–323. doi:10.1023/A:1009992321465. S2CID 11447864.

- ^ Marshall, Amandine (2015). "The child and the hoopoe in ancient Egypt". KMT. 72 (26.1): 59–63.

- ^ Deuteronomy Chapter 14:18 Archived 2019-01-22 at the Wayback Machine. mechon-mamre.org

- ^ Smith, Margaret (1932). The Persian Mystics 'Attar'. New York: E.P.Dutton and Company. p. 27.

- ^ Dupree, N (1974). "An interpretation of the role of the Hoopoe in Afghan folklore and magic". Folklore. 85 (3): 173–93. doi:10.1080/0015587X.1974.9716553. JSTOR 1260073.

- ^ Mall Hiiemäe, Forty birds in Estonian folklore IV. translate.google.com

- ^ Garth, Samuel; Dryden, John; et al. "'Metamorphoses' by Ovid".

- ^ Book 5, lines 6041 and 6046. Gower, John (2008-07-03). Confessio Amantis. Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ^ Kline, A.S. (2000). "The Metamorphoses: They are transformed into birds". Archived from the original on 2007-07-11. Retrieved 2009-02-17.

- ^ "Day in pictures". San Francisco Chronicle. Reuters. May 29, 2008. Archived from the original on January 28, 2012. Retrieved January 25, 2022.

- ^ Erlichman, Erez (30 May 2008). "Hoopoe Israel's new national bird". ynet.

- ^ "Illegal trade in wild birds in Morocco: photo-report". MaghrebOrnitho. 23 December 2013. Retrieved 2018-06-03.

- ^ "decrease". IUCN. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "extinct". Artfakta. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "conservation". Polska. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

- ^ "VU". BAFU. Retrieved 18 January 2022.

Sources edit

- Cramp, Stanley, ed. (1985). "Upupa epops Hoopoe". Handbook of the Birds of Europe the Middle East and North Africa. The Birds of the Western Palearctic. Vol. IV: Terns to Woodpeckers. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 786–799. ISBN 978-0-19-857507-8.