Discoverer 1 was the first of a series of satellites which were part of the CORONA reconnaissance satellite program. It was launched on a Thor-Agena A rocket on 28 February 1959 at 21:49:16 GMT from Vandenberg Air Force Base in California. It was a prototype of the KH-1 satellite, but did not contain either a camera or a film capsule.[4] It was the first satellite launched toward the South Pole in an attempt to achieve a polar orbit, but was unsuccessful. A CIA report, later declassified, concluded that "Today, most people believe the Discoverer 1 landed somewhere near the South Pole".[5]

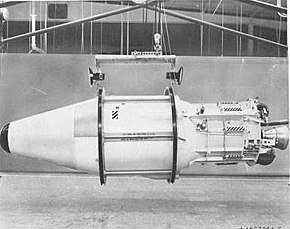

An Agena-A stage [1] | |

| Mission type | Technology |

|---|---|

| Operator | U.S. Air Force / CIA |

| Harvard designation | 1959 Beta 1 |

| COSPAR ID | 1959-002A |

| SATCAT no. | 00013 |

| Mission duration | 17 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft | Discoverer |

| Spacecraft type | CORONA Test Vehicle |

| Bus | Agena-A |

| Manufacturer | Douglas Aircraft Company |

| Launch mass | 618 kg |

| Dimensions | 5.73 m long 1.52 m diameter |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | 28 February 1959, 21:49:16 GMT |

| Rocket | Thor-Agena A (Thor 163 – FTV 1022) [2] |

| Launch site | Vandenberg, LC 75-3-4 |

| Contractor | Douglas Aircraft Company |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Deorbited |

| Decay date | 17 March 1959 |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Reference system | Geocentric orbit[3] |

| Regime | Low Earth orbit |

| Perigee altitude | 163 km |

| Apogee altitude | 968 km |

| Inclination | 89.7° |

| Period | 96.0 minutes |

The Discover program was managed by the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) of the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Air Force. The primary goal of the program was to develop a film-return photographic surveillance satellite to assess how rapidly the Soviet Union was producing long-range bombers and ballistic missiles and where they were being deployed, and to take photos over the Sino-Soviet bloc to replace the Lockheed U-2 spyplanes. It was part of the secret CORONA program which was also used to produce maps and charts for the Department of Defense and other U.S. government mapping programs. The goal of the program was not revealed to the public at the time; it was presented as a program to orbit large satellites to test satellite subsystems and investigate the communication and environmental aspects of placing humans in space, including carrying biological packages for return to Earth from orbit. In all, 38 Discoverer satellites were launched by February 1962, although the satellite reconnaissance program continued until 1972 as the CORONA project. The program documents were declassified in 1995.[3]

Discoverer 1 was a test of the performance capabilities of the propulsion and guidance system of the booster and satellite. The launch took place from Vandenberg Air Force Base on a Thor-Agena A. After first stage burnout at 28,529 km/h, the rocket coasted to an orbital altitude where the second stage guidance system-oriented the spacecraft by means of pneumatic nitrogen jets. The second stage engine ignited when the correct attitude was achieved, putting the spacecraft into a polar orbit where it remained until re-entry on 17 March 1959. Discoverer 1 became the first man-made object ever put into a polar orbit. The difficulty was encountered receiving signals after launch, but the satellite broadcast intermittently later in the flight.[3]

In 1959, it was believed to have obtained orbit with speculation that the protective nose cone over the antennas was ejected just before the Agena fired and that the Agena then rammed into the nose cone, damaging the antennas.[6]

Discoverer 1 was a 5.73 m long, 1.52 m diameter cylindrical Agena-A upper-stage capped by a conical nosecone. The satellite casing was made of magnesium. Most of the 18 kg payload, consisting of communication and telemetry equipment, was housed in the nosecone. It included a high-frequency low-power beacon transmitter for tracking and a radar beacon transmitter with a transponder to receive command signals and allow long-range radar tracking. Fifteen telemetry channels (10 continuous and 5 commuted) were used to relay roughly 100 aspects of spacecraft performance. Unlike future Discoverer flights, this one did not carry a camera or film capsule.[3]

The satellite launched atop a Thor-Agena rocket. The Thor used liquid oxygen and RP-1 as propellants. The Agena used hypergolic fuels to boost the satellite into polar orbit. This combination of Thor and Agena would become the first booster rocket to send a payload to orbit using 2 stages.

Five young men were in the launch crew of this historic mission placing the first spy satellite for the U.S. into polar orbit. The names of the young men, alphabetically, were James Boyle, Mark Jonah, John Lane, Jack Shields, the Test Conductor, and Erwin Warshawsky. Jack was 30 years of age. The others were all in their early to mid twenties.

Just months before, in 1958 this same launch crew launched the first Intermediate Range Ballistic Missile from the West Coast of the United States. A couple of years later, Mr. Mark Jonah was an Assistant Test Conductor for the Titan 1 ICBM weapons program at Vandenberg AFB and in 1961, at 27 years of age, was promoted to Test Conductor for the Titan II ICBM weapons system at Vandenberg AFB. He was the youngest person in the U.S. weapons program to be given the responsibility to integrate all the ground support equipment, flight control, guidance, propellant and pressurization systems, launch control, and all other systems and launch a fully operational ballistic missile 5,000 miles down range to target.

See also edit

References edit

- ^ "Discoverer 1".

- ^ https://www.thespacereview.com/article/1347/1 – 13 avril 2009

- ^ a b c d "Discoverer-1 1959-002A". NASA. 14 May 2020. Retrieved 6 January 2021. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Clayton K. S. Chun, Thunder Over the Horizon: From V-2 Rockets to Ballistic Missiles (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2006), pp. 74–75

- ^ David L. Hancock (1995). Kevin C. Ruffner (ed.). "CORONA: America's First Satellite Program" (PDF). Center for the Study of Intelligence. CIA Cold War series. CIA. p. 16. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2007. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ CIA.gov – 1995, p. 16 This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

External links edit

- KH-1 at Encyclopedia Astronautica

- https://web.archive.org/web/20071003082210/http://msl.jpl.nasa.gov/Programs/corona.html

- Day, Dwayne A. (13 April 2009). "Lost over the horizon: Discoverer 1 explores Antarctica". The Space Review.