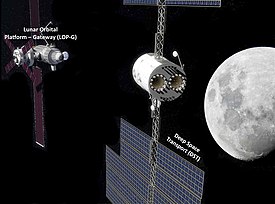

The Deep Space Transport (DST), also called Mars Transit Vehicle,[6] is a crewed interplanetary spacecraft concept by NASA to support science exploration missions to Mars of up to 1,000 days.[4][2][7] It would be composed of two elements: an Orion capsule and a propelled habitation module.[3] As of late 2019, the DST is still a concept to be studied, and NASA has not officially proposed the project in an annual U.S. federal government budget cycle.[5][8][9] The DST vehicle would depart and return from the Lunar Gateway to be serviced and reused for a new Mars mission.[2][10][11]

DST would comprise an Orion spacecraft and a propelled habitation module | |

| Mission type | Crewed Mars orbiter |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| Mission duration | 1–3 years |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Launch mass | 100 metric tons[1][2][3] |

| BOL mass | Habitat: 48 tons (includes 21 tons Habitat with 26.5 tons cargo[1]) Electric propulsion system: 24 tons[1] Chemical propellant: 16 tons[1] |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | Suggested shakedown: 2027[4] Potential Mars launch: 2037[5] |

| Rocket | Space Launch System (SLS) |

| Launch site | LC-39B, Kennedy Space Center |

| Transponders | |

| Band | Dual: radio and laser comm[4][6] |

| Bandwidth | Ka band[6] |

Architecture overview edit

Both the Gateway and the DST would be fitted with the International Docking System Standard.[2] The DST spacecraft would comprise two elements: an Orion capsule and a habitation module[3] that would be propelled by both electric propulsion and chemical propulsion, and carry a crew of four in a medium-sized habitat.[4] The fully assembled spacecraft with the Orion capsule mated would have a mass of about 100 metric tons.[1][2][3] The spacecraft's habitat portion will likely be fabricated using tooling and structures developed for the SLS propellant tank;[12] it would be 8.4 m (28 ft) in diameter and 11.7 m (38 ft) in length.[12]

The habitat portion of the DST spacecraft may also be equipped with a laboratory with research instrumentation for physical sciences, electron microscopy, chemical analyses, freezers, medical research, small live animal quarters, plant growth chambers, and 3D printing.[12] External payloads might include cameras, telescopes, detectors, and a robotic arm.[12]

Its initial target for exploration is Mars (flyby or orbit), and other suggested destinations are Venus (flyby or orbit), and a sample return from a large asteroid.[13] If the DST spacecraft were to orbit Mars, it would enable opportunities for real-time remote operation of equipment on the Martian surface, such as a human-assisted Mars sample return.[13][14]

It would use a lunar flyby to build up speed and then using solar electric propulsion (SEP) it would accelerate into a heliocentric orbit. There it would complete its transit to Mars or other possible destinations. It would use chemical propulsion to enter Mars orbit. Crews could perform remote observations or depart for the surface during a 438-day window. The vehicle would depart Mars orbit via a chemical burn. It would use a mix of SEP and lunar gravity assists to recapture into Earth's sphere of influence.[15]

| Fully assembled DST | Estimated mass[1][6] (metric tons) |

|---|---|

| Orion capsule (launched separately) |

10.3

|

| Habitat | 21.9

|

| Cargo | 26.5

|

| Solar electric propulsion system including xenon propellant |

24

|

| Chemical propellant | 16

|

| Estimated total | 98.7

|

Suggested timeline edit

If funded, the DST would be launched toward the Lunar Gateway in one SLS cargo flight,[2] probably in 2027.[4] The spacecraft would be expected to undergo 100–300 days of DST Habitat crewed operation before[3] it starts a one-year long flight test (shakedown cruise) in cislunar space in 2029 at the earliest.[4][2] It would be designed to transport a crew to orbit Mars, but not land, in the 2030s.[4] Its first mission would likely involve a Venus flyby and a short stay around Mars.[6] Additional developments and vehicles would be required for a Mars human surface mission.[3]

In August 2019, the Science and Technology Policy Institute (STPI) delivered a report commissioned by NASA in 2017 specifically for a technical and financial assessment of "a Mars human space flight mission to be launched in 2033" using the DST.[5] The report concluded that "even without budget constraints, a Mars 2033 orbital mission cannot be realistically scheduled under NASA's current and notional plans," and that "the analysis suggests that a Mars orbital mission could be carried out no earlier than the 2037 orbital window without accepting large technology development, schedule delay, cost overrun, and budget shortfall risks."[5] A mission to Mars launching in 2033, the report concluded, would need to have life support systems and propulsion tested by 2022, which is unlikely.[5] The report estimated that the total cost of the elements needed for the Mars mission, including SLS, Orion, Gateway, DST and other logistics, at $120.6 billion through fiscal year 2037.[5]

See also edit

- Deep Space Habitat

- Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships

- Mars Base Camp, Lockheed's concept of the DST

- Project Prometheus

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f Deep Space Transport (DST) and Mars Mission Architecture. (PDF) John Connolly. NASA Mars Study Capability Team. Published: October 17, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g NASA Unveils the Keys to Getting Astronauts to Mars and Beyond. Neel V. Patel, The Inverse. April 4, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Deep Space Gateway -Enabling Missions to Mars — Shakedown Cruise Simulating Key Segments of Mars Orbital Mission. Mars Study Capability Team (2018). Michelle Rucker, John Connolly. NASA.

- ^ a b c d e f g Finally, some details about how NASA actually plans to get to Mars. Eric Berger, ARS Technica. March 28, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Independent report concludes 2033 human Mars mission is not feasible. Jeff Foust, Space News. 18 April 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Human Exploration and Operations Mission Directorate - Architecture Status. (PDF) Jim Free. NASA. March 28, 2017.

- ^ Deep Space Transport approaches the Deep Space Gateway. The Planetary Society.

- ^ Cislunar station gets thumbs up, new name in President’s budget request. Philip Sloss, NASA Spaceflight. March 16, 2018.

- ^ NASA evaluates EM-2 launch options for Deep Space Gateway PPE. Philip Sloss, NASA Spaceflight. December 4, 2017.

- ^ Kathryn Hambleton (March 28, 2017). "Deep Space Gateway to Open Opportunities for Distant Destinations". NASA. Archived from the original on September 27, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ Robyn Gatens, Jason Crusan. "Cislunar Habitation & Environmental Control & Life Support System" (PDF). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 31, 2017. Retrieved March 31, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Smitherman, David; Needham, Debra; Lewis, Ruthan (February 28, 2018). Research Possibilities Beyond Deep Space Gateway (PDF). Deep Space Gateway Concept Science Workshop. February 27 – March 1, 2018. Denver, Colorado.

- ^ a b MacDonald, Alexander C. (2017). Towards an Interplanetary Spaceship: The Potential Role of Long-Duration Deep Space Habitation and Transportation in the Evolution and Organization of Human Spaceflight and Space Exploration (PDF). AIAA SPACE and Astronautics Forum and Exposition. September 12–14, 2017. Orlando, Florida. AIAA 2017-5100.

- ^ Gillard, Eric (April 25, 2018). "NASA Langley Talk to Highlight Sending Humans to the Deep Space Gateway" (Press release). NASA. Retrieved May 20, 2018.

- ^ "Deep Space Transport (DST) and Mars Mission Architecture" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 29, 2019.