The Codex Tovar (JCB Manuscripts Codex Ind 2) is a historical Mesoamerican manuscript from the late 16th century written by the Jesuit Juan de Tovar and illustrated by Aztec painters, entitled Historia de la benida de los Yndios a poblar a Mexico de las partes remotas de Occidente (History of the arrival of the Indians to populate Mexico from the remote regions of the West). The codex is close in content, but not identical, to the Ramírez Codex.[1] It is currently kept at the John Carter Brown Library, in Providence, Rhode Island, United States.

Creation and contents edit

The Tovar Codex was created between 1587 and 1588 by the Jesuit historian Juan de Tovar, who worked under the auspices of the historian José de Acosta. Some letters exchanged between Acosta and Tovar, explaining the history of the manuscript, are present in the volume. It seems that Tovar, who arrived in New Spain in 1573, had been commissioned by the Jesuit order to prepare a history of the Aztec kingdom based on credited indigenous sources; however, his lack of familiarity with the pictographic and hieroglyphic writing system of the Aztec impaired his work considerably. Hence, Tovar met with Aztec historians and manuscript painters (tlacuiloque) to transform these pictoglyphic sources into an account more acceptable to the Western historical tradition.[2] The first result of Tovar's historical research was the Ramírez Codex.[3]

Later, in 1583, the Jesuit historian and naturalist José de Acosta arrived in New Spain. He had the intention of gathering manuscripts to prepare himself a history of the Aztec, but failed to procure for himself good manuscripts. Having failed in his task and having left New Spain, he reached out to his colleague Tovar, who was already advanced in the preparation of the Ramírez Codex. He encouraged Tovar to send a copy of his work to King Philip II of Spain, who at the time requested historical works on his American domains to be prepared: hence, the Ramírez Codex remained in Mexico, where it was later re-found, and the Tovar Codex was sent to Spain, where Acosta used the valuable information from the manuscript to write the section on Aztec history in his more general work Historia natural y moral de las Indias.[3]

The Manuscript can be divided in four sections. The first is the epistolary exchange between Acosta and Tovar. The second is the Relación or history proper. The third is a treatise on Aztec religion (Tratado de los ritos). The final part is a calendar showing the Aztec months and correlating them to the European calendar via dominical letters.[4] The contents and illustrations of the first and the historical part are noticeably close not only to the Ramírez Codex, but also to the work of Diego Durán, and Fernando Alvarado Tezozomoc. This group of works have been hypothesized by R. H. Barlow to derive from an earlier, lost work, labelled by him as Crónica X.[5] Some scholars consider that Tovar derived both of his works from Durán, given the similarities among them,[6] while others hypothesize that both come from the same group of pictographic Aztec documents, now lost.[7]

The historical section of the Codex Tovar edit

-

Chicomoztoc, the seven caves of origin at Aztlan

-

Tollan

-

The battle at Chapultepec

-

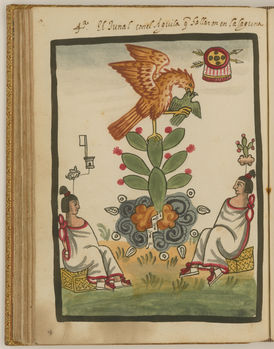

The founding of Tenochtitlan

-

Acamapichtli, the first Aztec tlatoani

-

Huitzilihuitl, the second Aztec tlatoani

-

Chimalpopoca, the third Aztec tlatoani

-

Itzcoatl, the fourth Aztec tlatoani

-

The battle of Azcapotzalco

-

The war against Coyoacan

-

An Aztec noble sacrifices his own life

-

The funerary rites of Ahuizotl

-

Moctezuma, the fifth Aztec tlatoani

-

Tizoc, the seventh Aztec tlatoani

-

Axayacatl, the seventh Aztec Tlatoani

-

Ahuizotl, the ninth Aztec tlatoani

-

The sorcerers received the water of the Cuextecatl spring

-

Moctezuma, the last Aztec emperor

Publication history edit

During the XIX century, the manuscript left Spain, being bought by Sir Thomas Phillipps circa 1837. Phillips attempted to publish the manuscript, but he was only able to publish 23 pages of the manuscript in an incomplete edition, which is exceedingly rare.[2] In 1946, the manuscript was sold in an auction to the John Carter Brown Library, where it is housed today, although a scholar, Omar Saleh Cambreros, proposes that given some slight differences between Phillipps publication and the current-day manuscript, a possibility exists that the actual Tovar Manuscript is lost. The manuscript has been published in different occasions: the calendrical section by Kubler and Gibson,[8] and a transcription and a French translation of the whole, along with the plates of the historical section only, by Jacques Lafaye.[4]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Handbook of Middle American Indians. Volume fourteen, volume fifteen, Guide to ethnohistorical sources. Robert Wauchope, Howard Francis Cline, Charles Gibson, H. B. Nicholson, Tulane University. Middle American Research Institute. Austin. 2015. pp. 225–226. ISBN 978-1-4773-0687-1. OCLC 974489206.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Tovar, Juan de (1860). Thomas Phillipps, Bart (ed.). Historia de los yndios mexicanos. Cheltenham: Jacobus Rogers. p. 2.

- ^ a b Saleh Camberos, Omar (2011). "Historia y Misterios del Manuscrito Tovar" (PDF). Revista Digital Sociedad de la Información. 35.

- ^ a b Manuscrit Tovar : origines et croyances des indiens du Mexique ... Jacques Lafaye. Graz: Akademische Druck u. Verlagsanstalt. 1972. ISBN 3-201-00247-X. OCLC 468492861.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Barlow, R. H. (1990). Los mexicas y la Triple Alianza. Jesús. Monjarás-Ruiz, Elena Limón, Maricruz Paillés H. (1 ed.). México, D.F.: INAH. ISBN 968-6254-04-8. OCLC 25412072.

- ^ Leal, Luis (1953). "El Codice Ramirez". Historia Mexicana. 3 (1): 11–33. ISSN 0185-0172. JSTOR 25134307.

- ^ Tena, Rafael (1997). "Revisión de la hipótesis sobre la Crónica X". Códices y documentos sobre México : segundo simposio. Salvador Rueda Smithers, Constanza Vega Sosa, Rodrigo Martínez Baracs, Simposio de Códices y Documentos sobre México (1 ed.). México, D.F.: Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Dirección de Estudios Históricos. pp. 163–178. ISBN 970-18-0020-6. OCLC 39146635.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Tovar, Juan de (1951). Kubler, George; Gibson, Charles (eds.). The Tovar calendar; an illustrated Mexican manuscript ca. 1585. Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts & Sciences, v. 11. New Haven: The Academy.