The blue-tailed hummingbird (Saucerottia cyanura) is a species of hummingbird in the "emeralds", tribe Trochilini of subfamily Trochilinae. It is found in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, and Nicaragua.[4][3]

| Blue-tailed hummingbird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Saucerottia cyanura | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Clade: | Strisores |

| Order: | Apodiformes |

| Family: | Trochilidae |

| Genus: | Saucerottia |

| Species: | S. cyanura

|

| Binomial name | |

| Saucerottia cyanura | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Amazilia cyanura[3] | |

Taxonomy and systematics edit

The blue-tailed hummingbird was formerly placed in the genus Amazilia. A molecular phylogenetic study published in 2014 found that the genus Amazilia was polyphyletic. In the revised classification to create monophyletic genera, the blue-tailed hummingbird was moved by most taxonomic systems to the resurrected genus Saucerottia.[5][6][4][7][8] However, BirdLife International's Handbook of the Birds of the World retains it in Amazilia.[3]

Three subspecies are recognized, the nominate S. c. cyanura, S. c. guatemalae, and S. c. impatiens.[4]

Description edit

The blue-tailed hummingbird is 9 to 10 cm (3.5 to 3.9 in) long. One male specimen weighed 3.9 g (0.14 oz) and females weigh about 4.5 g (0.16 oz). Both sexes of all subspecies have a black bill with a reddish base to the mandible. Males of the nominate subspecies have a deep metallic green crown and back, a dull purplish bronze rump, and dark metallic bluish uppertail coverts. Their primaries and secondaries are chestnut and show as a patch on the closed wing. Their tail is dark metallic violet blue. Their underparts are mostly bright metallic green with dull steel blue undertail coverts. Females are similar to males but duller. Their rump is less purplish and their underparts' feathers usually have narrow whitish margins. Their belly has some dull buffy whitish mixed in and their undertail coverts are grayish.[9]

Subspecies S. c. guatemalae is much darker than the nominate. The chestnut on the wings is darker, the tail's blue more violaceous to metallic purple, and the undertail coverts dark steel blue to blue-black. S. c. impatiens is somewhat larger than the nominate. Its head and back are darker green, the rufous or cinnamon patch on the wings is larger, and the undertail coverts are dull steel blue with rich ferruginous edges.[9]

Distribution and habitat edit

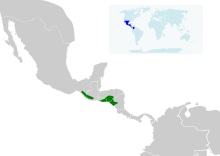

The blue-tailed hummingbird subspecies S. c. guatemalae is found on the Pacific slope from southeastern Chiapas in Mexico to southern Guatemala. The nominate S. c. cyanura is found in southern Honduras, eastern El Salvador, and northwestern Nicaragua. S. c. impatiens is found in northwestern and central Costa Rica. (The map omits this last subspecies' range.) It inhabits a variety of semi-open landscapes such as the edges and clearings of humid and dry oak and pine forest, secondary forest, scrublands, and shade coffee plantations. In elevation it ranges between 100 and 1,800 m (330 and 5,900 ft) in Mexico and Guatemala and from near sea level to 1,200 m (3,900 ft) in El Salvador, Honduras, and Nicaragua.[9]

Behavior edit

Movement edit

The blue-tailed hummingbird's movements, if any, have not been documented.[9]

Feeding edit

The blue-tailed hummingbird forages for nectar at all levels of its habitat. Though details of its diet are lacking, it is known to frequent Inga trees. It is assumed to also consume insects like other hummingbirds.[9]

Breeding edit

Nothing is known about the blue-tailed hummingbird's breeding phenology. Its nest and eggs have not been described.[9]

Vocalization edit

The blue-tailed hummingbird's song is "a short twitter". Its calls include "a hard, raspy bzzzrt ... hard chips, and high, sharp siik!, the last of which it makes in flight.[9]

Status edit

The IUCN has assessed the blue-tailed hummingbird as being of Least Concern. It has a large range and an estimated population of at least 50,000 mature individuals, though the latter is believed to be decreasing. No immeditate threats have been identified.[1] "Human activity probably has little short term effect on [the] Blue-tailed Hummingbird."[9]

References edit

- ^ a b BirdLife International (2021). "Blue-tailed Hummingbird Amazilia cyanura". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021. Retrieved 6 September 2022.

- ^ "Appendices | CITES". cites.org. Retrieved 2022-01-14.

- ^ a b c HBW and BirdLife International (2021) Handbook of the Birds of the World and BirdLife International digital checklist of the birds of the world. Version 6. Available at: http://datazone.birdlife.org/userfiles/file/Species/Taxonomy/HBW-BirdLife_Checklist_v6_Dec21.zip retrieved August 7, 2022

- ^ a b c Gill, F.; Donsker, D.; Rasmussen, P., eds. (August 2022). "Hummingbirds". IOC World Bird List. v 12.2. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ McGuire, J.; Witt, C.; Remsen, J.V.; Corl, A.; Rabosky, D.; Altshuler, D.; Dudley, R. (2014). "Molecular phylogenetics and the diversification of hummingbirds". Current Biology. 24 (8): 910–916. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.016. PMID 24704078.

- ^ Stiles, F.G.; Remsen, J.V. Jr.; Mcguire, J.A. (2017). "The generic classification of the Trochilini (Aves: Trochilidae): Reconciling taxonomy with phylogeny". Zootaxa. 4353 (3): 401–424. doi:10.11646/zootaxa.4353.3. PMID 29245495.

- ^ "Check-list of North and Middle American Birds". American Ornithological Society. August 2022. Retrieved August 9, 2022.

- ^ Clements, J. F., T. S. Schulenberg, M. J. Iliff, S. M. Billerman, T. A. Fredericks, J. A. Gerbracht, D. Lepage, B. L. Sullivan, and C. L. Wood. 2021. The eBird/Clements checklist of Birds of the World: v2021. Downloaded from https://www.birds.cornell.edu/clementschecklist/download/ Retrieved August 25, 2021

- ^ a b c d e f g h Arizmendi, M. d. C., C. I. Rodríguez-Flores, C. A. Soberanes-González, and T. S. Schulenberg (2021). Blue-tailed Hummingbird (Saucerottia cyanura), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (T. S. Schulenberg, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.blthum1.01.1 retrieved September 6, 2022