This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. (June 2017) |

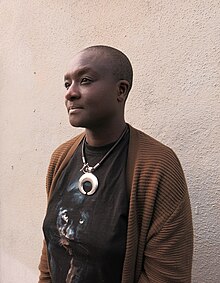

Bintou Dembélé is a dancer and a choreographer who is recognized as one of the pioneer figures of Hip hop dance in France.[1] After having danced for more than thirty years in the Hip Hop world, Bintou Dembélé has been the artistic director of her own dance company Rualité since 2002.[1][2] Her work explores the issue of the memory of the body through the prisms of colonial and post-colonial French history.[3][4]

Beginnings edit

Bintou Dembélé was born on 30 March 1975 in the suburbs of Paris to a family who emigrated to France after Sub-Saharan Africa's decolonization.[1] Bintou started dancing with her brothers when she was only ten years old; her interest in Hip Hop dance was in part influenced by the show H.I.P. H.O.P. on the French TV channel TF1.[1] Around 1985, Bintou Dembélé and her friends Gérard Léal et Anselme Terezo created the dance group Boogie Breakers and started dancing collectively in their neighborhood's public spaces.[1] In 1989, she joined the group Concept of Art,[1][5] in which was born several collectives of rappers and dancers. While in middle school, Bintou Dembélé also joined the dance groups Aktuel Force (in 1993 and 1997) and Mission Impossible (1994-1996) in which she diversified her Hip Hop dancing by learning House Dance, New Style, Break Dancing... etc.[1] She progressively acquired her dance technique and street credibility through collective trainings. She practiced in emblematic parisian spots for the French street dances as in Châtelet les Halles, the Place du Trocadéro-et-du-11-Novembre, the Place Georges-Pompidou and La Défense. In addition to her participation to different collectif trainings in Paris, she gets involved in street shows, festivals, battles and national scale Hip Hop competitions.[6][7] She also takes part in different shows in nightclubs in Belgium, at Le Palace (Paris), le Bataclan or Le Divan du Monde.[1]

Professional career edit

Dembélé's professional career began in 1996 when she was recruited by the Théâtre Contemporain de la Danse de Paris (TCD) as a dancer and choreographer.[1] In 1997, she joined the dance group the Collectif Mouv’ where she created her first show entitled Et si…! (What if...!) with the break dancer Rabah Mahfoufi.[1] While dancing for the Collectif Mouv', Dembélé also collaborated with the French Jazz saxophonist Julien Lourau and with the musical organization the Groove Gang to create a show entitled Come fly with us.[1] At the same time she also co-founded the dance group Ykanji and the female group dance Ladyside.[1] Her participation in French popular TV shows such as Graines de stars or Hit Machine enabled Dembélé to meet French rappers and dancers such as MC Solaar and Bambi Cruz.[1] In 1998, she danced for MC Solaar's concert in l'Olympia (Paris) in a show choreographed by Max-Laure Bourjolly and Bambi Cruz.[1] In 2002, as an interpreter for the dance company Käfig, Dembélé performed at the Joyce Theater in Manhattan during the New York New Europe '99 Festival.[8] The same year, she also created her own dance compagny, named Rualité.[1][2] In 2004 Dembélé created and performed her third show entitled L'Assise (The Foundation), which recounted the creative journey of individuals who explored the Hip Hop culture in France.[9] In 2010, she created her first solo show entitled Mon appart' en dit long (My apartment tells a lot about it), in which she explored the notion of femininity, spatiality and daughter-mother relationship.[10] In 2011, she choreographed the music video of the song Roméo kiffe Juliette of the French slam singer Grand Corps Malade.[1] In 2013, she created and performed in Z.H. (an abbreviation for 'zoo humains', which means in English human zoos). Z.H, which is one of Dembélé's major creations, was created for six dancers and explored the notions of memory, imperial gaze and voyeurism, racism and the dehumanization of people of color.[11][3] In 2016, she created and performed in S/T/R/A/T/E/S - Quartet et le duo (S/T/R/A/T/U/M - Duo quartet), a dancing and musical performance for two duos mixing improvisation, dance theater, gimmick and 'corporeal poetry' to interrogate the notions of the transmission of traumatic memory, of feminism and of post-colonial identities.[12] As a recognized dancer with both a street and professional background, Dembélé participates as a judge in various battles and other Hip Hop dance competitions and trains dancers as interprets for live performances all over the world.[1] Bintou and the dancers of her dance compagny Rualité have performed their shows in France and internationally (in Sweden, in Burma, in Chile, in Macedonia, in French Guiana and in Mali).

Commitments edit

Rualité 's aim is to explore new forms of political engagements and representations by gathering diverse artists and researchers.[2] The photograph and video maker Denis Darzacq and the anthropologist of colonial representations Sylvie Chalaye are one of the personalities linked to Rualité.[2] Organized around the ideas of creation, transmission and research, Rualité not only produces dance shows but also works for enhancing the access to culture and to cultural activities both in the French metropole (and especially in its most marginalized communities) and in its overseas territories (and more especially in French Guiana).[2] In the context of her company, Bintou Dembélé frequently animates pedagogical and/or exploratory workshops aiming to gather people from different backgrounds and orientations in order to produce new insights on what being a committed artist means.[2] Bintou Dembélé's engagements led her to work with students and scholars in schools and universities, with musicians and dancers from different backgrounds as well as with some of the Parisian suburbs' carceral population.[2]

Bintou Dembélé's commitment to the development of the Hip Hop culture and to the recognition and legitimacy of its actors in the French public spaces and common discourse led her to integrate the SeFeA laboratory organized by Université Sorbonne Nouvelle - Paris 3 in 2014.[2][13] In September 2016, she is hosted by the Gender and Women studies department of the University of California, Berkeley in a conference to talk about the video documentary of her performance Z.H.[14] In the French and francophone contexts, Bintou Dembélé's work can be related to the one of Maboula Soumahoro, Alice Diop or Isabelle Boni-Claverie.[15] Bintou Demélé is one of the spokesperson of the scholars Mame-Fatou Niang and Kaytie Nielsen recent documentary Mariannes Noires (Black Mariannes) whose aim is to give voice and make visible Afro-French female identities.[16][17]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Africultures (2014). "Un témoignage de Bintou Dembele: S/T/R/A/T/E/S. Trente ans de Hip-Hop dans le corps" (3 (n° 99 - 100)): 250–261.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b c d e f g h "Compagnie Rualité - Collectif12". Collectif12. Retrieved 2017-02-26.

- ^ a b Foundation, Magenta. "Le Hip Hop de Bintou Dembélé contre le racisme (France)". I CARE - News - Internet Centre Anti Racism Europe. Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- ^ Africultures. "S/T/R/A/T/E/S de Bintou Dembele". Retrieved 2017-02-22.

- ^ Thierry, Gustave (2014). "Un témoignage de Thierry Gustave " Steevy Gustave. Un rhizome entre l'art et la politique "". Africultures. (n° 99 - 100) (3): 262–269.

- ^ McCarren, Felicia (2013). French moves: the cultural politics of le hip hop (2013 ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Shapiro, Roberta (2004). "The Aesthetics of Institutionalization: Breakdancing in France". Journal of Arts Management. 4: 316 (Law & Society 33).

- ^ Kisselgoff, Anna (16 May 2002). "DANCE REVIEW; Hip-Hop Head-Spinning, But With a French Twist". The New York Times. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ "Break Dancing session". lacigale.fr. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ Bartolucci, Enrico (2011). "Bintou Dembélé 'Mon appart' en dit long'". vimeo.fr. Retrieved 28 March 2017.

- ^ Arquié, Marie (13 March 2013). "'Z.H' de Bintou Dembélé". novaplanet.com. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ^ Kabuya, Ramcy (19 July 2016). "S/T/R/A/T/E/S de Bintou Dembele". africultures.com. Africultures. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ "Laboratoire SeFea". Afritheatre.com. Afrithéâtre: Théâtre contemporains du monde noir francophone. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ Facebook event, Z.H le film (20 September 2016). "Z.H // UC Berkeley". Facebook. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

{{cite web}}:|last1=has generic name (help) - ^ Dechaufour, Pénélope (2014). "Tisser sa trame". Africultures. (n° 99 - 100) (3): 8–15.

- ^ Candy, Eye (16 February 2017). "Black and French: 'Mariannes Noires' film explores the intersections of identity". afropunk.com. Afropunk magazine. Archived from the original on 13 April 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- ^ Mariannes Noires le film (7 February 2017). "Mariannes Noires - film teaser". youtube.com. Mariannes Noires le film. Retrieved 22 March 2017.