The Battle of Puketutu (Māori: Puketutu) was an engagement that took place on 8 May 1845 between British forces, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Hulme, and Māori warriors, led by Hōne Heke and Te Ruki Kawiti, during the Flagstaff War in the Bay of Islands region of New Zealand.

| Battle of Puketutu | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Flagstaff War | |||||||

A print of the Battle of Puketutu; Heke's pā is at left centre, while the British assault parties are battling Kawiti's warriors in the distance to the right | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Māori | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

William Hulme George Johnson Tāmati Wāka Nene |

Hōne Heke Te Ruki Kawiti | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

Allied Māori

|

Māori

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

British Army

Royal Navy

Allied Māori

|

Māori

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

13 killed 30–40 wounded |

30 killed 50 wounded | ||||||

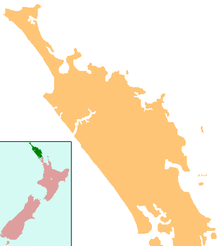

Site of the Battle of Puketutu | |||||||

After Heke and Kawiti's sacking of the Bay of Islands town of Kororāreka in March 1845, the opening act of the Flagstaff War, the British retaliated with a punitive expedition to the area. After destroying the pā (hillfort) of a local chief at nearby Otuihu on 30 April, the British moved inland, led by a Māori ally, Tāmati Wāka Nene. They planned to attack Heke's pā at Puketutu, reaching the area on 7 May after a difficult march through dense bush. The battle commenced on the morning of 8 May, with three parties of British soldiers and sailors advancing to an area behind the pā whereupon they were ambushed by Kawiti's warriors. For the next few hours, there were repeated sallies back and forth until the British retreated, leaving Heke in command of the battlefield. He subsequently abandoned the pā. The Battle of Puketutu, the first attack mounted by the British on an inland pā, is regarded as a victory for Heke and Kawiti although at the time the British declared that the Māori had been defeated by virtue of exaggerated claims of the number of their warriors that had been killed in the engagement.

Background edit

The Treaty of Waitangi signed on 6 February 1840 by Captain William Hobson, on behalf of the British Crown, and several Māori rangatira (chiefs) from the North Island of New Zealand, established British sovereignty over New Zealand. The Māori signatories understood that they would benefit from the protection provided by the British while still retaining authority over their affairs.[1]

In the Bay of Islands, dissatisfaction and resentment at the Crown's interference in local matters soon arose, with many Māori believing that its actions, such as introducing custom fees and the relocation of the colony's capital from Okiato south to the new settlement of Auckland, were contrary to their understanding of the Treaty of Waitangi. Hōne Heke, a prominent rangatira of the Ngāpuhi iwi (tribe) was angered at what he deemed to be the loss of his authority. As a protest, between July 1844 and January 1845, Heke chopped down the flagstaff, which was a symbol of British control, at the town of Kororāreka on three separate occasions.[2][3][4]

Heke's actions were a major affront to the Crown, affecting its credibility and authority.[5] Following the last felling of the flagstaff, Governor Robert FitzRoy significantly increased the military presence in Kororāreka, sending 140 men of the 96th Regiment from Auckland to reinforce the existing garrison of 30 soldiers. A blockhouse was constructed on Maiki Hill, just north of the town, at the top of which a replacement flagstaff was erected. A Royal Navy vessel, the sloop HMS Hazard, was present in the bay as well.[6]

Battle of Kororāreka edit

The opening act of the Flagstaff War[Note 1] was on 11 March, when Heke and a taua (war party) of 150 warriors, along with another taua of 200 warriors, commanded by the Ngāpuhi rangatira and Heke ally, Te Ruki Kawiti, attacked Kororāreka. The latest flagstaff was successfully cut down and the British rousted from the newly built blockhouse. Heke, who had achieved his objective, called a truce at midday; it was never his intention to threaten the residents of Kororāreka but to force redress from the Crown colony government for his grievances. Regardless the British decided to evacuate the town's women and children. As people embarked for the vessels in the bay, the town's gunpowder stocks exploded, either deliberately or accidentally, which led to panic. All of the townspeople were taken to the vessels and Kororāreka was abandoned. Hazard bombarded the town before taking its passengers to Auckland. Kororāreka was subsequently looted, not only by Heke's and Kawiti's men but other local Māori as well. Even some settlers participated in the looting.[7][8][9]

Government response edit

The loss of Kororāreka was humiliating for the colonial government.[10][11] On hearing news of Kororāreka, receiving its refugees and fearing a Ngāpuhi attack on Auckland, a number of that town's settlers sold their property and sailed for Australia.[12] Lacking resources for an immediate response to the Ngāpuhi threat, FitzRoy asked for reinforcements from Sir George Gipps, the Governor of New South Wales. He also set about raising a militia.[10][11] FitzRoy found a Māori ally in the Bay of Islands in the form of Tāmati Wāka Nene, another rangatira of the Ngāpuhi iwi but one aligned with the Crown. Angered by Heke's actions, he undertook to support the government response.[13] He initially did so by establishing a pā (hillfort) at Ōkaihau, intending to disrupt Heke's movements inland.[14] There were repeated skirmishes between Nene's taua and that of Heke during April.[15]

In the meantime, FitzRoy could do little with the forces he had at his disposal and waited for the requested reinforcements from Sydney. When these, 215 men of the 58th Regiment, arrived, he acted quickly and, on 26 April, dispatched HMS North Star, a post ship, north to the Bay of Islands with a force under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Hulme.[16][17] This force was composed of 320 soldiers of the 58th and 96th Regiments, 40 militia, plus 61 Royal Navy personnel from North Star and Hazard as well as 26 Royal Marines. The naval contingent, which included a battery of Congreve rockets with eight seamen commanded by Lieutenant Egerton, was led by Commander George Johnson, the acting captain of Hazard.[18][19][20] The British were equipped with 1839 percussion smoothbore muskets, although some may have had older flintlock muskets. The muskets were able to have bayonets attached and each man carried around 120 rounds of ammunition. The sailors also had cutlasses.[21][22]

The British secured Kororāreka on 28 April and then two days later mounted a punitive expedition on the coastal pā of Pōmare at Otuihu,[17] on a headland around 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) to the south of Kororāreka.[23] It was believed that many of Pōmare's tribe had been involved in the looting of Kororāreka, with suspicions that some may also have been involved in the attack as well. Pōmare, detained when he came to parley with Hulme, ordered his men to lay down their arms and leave the pā, which was set on fire. Its destruction removed a potential threat to the British flank as they moved inland in pursuit of Heke and Kawiti.[16][17][24]

Heke in the meantime, aware of the arrival of Hulme's force in the Bay of Islands, began building a pā at Puketutu.[16] The site itself had little value to Heke; it was isolated, difficult to approach and the surrounding land was not used for cultivation of food crops. Instead, it was intended to draw the British into an attack and therefore use up resources and manpower.[25]

Plan of attack edit

Hulme proposed to retaliate against the Ngāpuhi duo of Kawiti and Heke by attacking the former's pā at Waiōmio,[17] which was up a tributary of the Kawakawa River.[26] When it became apparent that it would be difficult to move troops there, this plan was abandoned. When Hulme consulted with a local missionary, Henry Williams, he discovered that what he had assumed were roads on a crude map were actually rivers and streams. This would complicate the movements of his troops as well as logistics and supply. It was also pointed out to Hulme that there were few Māori allied to the government along the route, leaving his lines of communications vulnerable. Urged by Nene, it was then decided to attack Heke's pā at Puketutu. Nene's pā at Ōkaihau was only 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) from Puketutu, and his taua would be able to support the British.[17][27]

Nene recommended that Hulme's forces approach Puketutu via the Kerikeri River and then move overland. Heke was expecting the British to come up the Waitangi River and had posted pickets along the route. Nene's proposed route, to which Hulme agreed, was advantageous in that it offered a better opportunity to surprise Heke, required fewer river crossings, and would also mean any attacks on the British as they marched to Puketutu would occur over open ground.[17][18]

Prelude edit

Hulme disembarked his force at Onewhero Bay, near Kerikeri, on 3 May.[16] Led by Nene's scouts, the British marched across the countryside. Despite being lightly loaded, moving through the terrain proved to be quite difficult for the soldiers. Historian Ron Crosby speculates it may have been that Nene, used to easily traversing the bush with his warriors, overestimated how readily the British could march. Nene, out of respect for the missionaries' desire to not have soldiers on their property, also bypassed the mission station at Waimate which lay on the route of the march. Dense bush hindered their movements and the first night saw the soldiers, lacking tents, rained upon which wet their gunpowder. The next day they diverted to the Church Mission Society (CMS) station at Kerikeri in order to dry out their equipment. The march resumed on 6 May and by the end of the day they had reached Ōkaihau.[28][29]

The arrival of Hulme's force in the Bay of Islands had not gone unnoticed and Heke's scouts were tracking its progress from Onewhero Bay.[28] Despite the events at Kororāreka, there was still a high regard for the fighting prowess of the British soldiers.[19] Heke originally had around 700 warriors at his disposal but many, on hearing of the British presence, left, leaving around 200 men manning the pā. However, on 7 May, he was reinforced when Kawiti and 140 of his taua arrived at Puketutu. Kawiti opted to base his force outside the pā.[16][28] Although Hulme and a number of his officers made a reconnaissance of Puketutu the same day, Kawiti's arrival at Puketutu went unnoticed.[30] A local CMS missionary, Reverend Robert Burrows, met with Heke and implored him to surrender. Heke demurred, indicating that he would wait for the British to attack.[31] Burrows noted the presence of Kawiti's forces but chose not to inform Hulme on the grounds of maintaining his neutrality.[30]

Puketutu edit

Heke's pā, which he named Te Kahika, at Puketutu on the northeast side of Lake Ōmāpere,[Note 2] was a rectangular work estimated to be 55 metres (180 ft) by 37 metres (121 ft), with flanking projections on three sides.[33][34] There was high ground to both the northwest and eastern sides, the latter backing onto dense bush in the direction of the extinct volcano Te Ahuahu. The pā lacked a source of water so a breastwork was thrown up on the southern slope, leading towards the lake; this provided means for accessing water.[30][35][36]

The pā was enclosed by two, and in some places, three lines of palisade, each 3 metres (9.8 ft) high and made up of tree trunks dug about 1.22 metres (4.0 ft) into the ground. The innermost palisade of close set posts had a large stone breastwork on the inside, and trench firing positions, wide enough for a person, dug all round the outside. A second palisade of close set posts was present on two sides. The outermost palisade, of smaller 255-millimetre (10.0 in) diameter posts, supported the pekerangi or ball-proof screen of flax, set above the ground to enable a view of the enemy at that level. Huts and buildings within the pā were roofed in green flax as means of fire prevention. Bastions enabled fire to be directed along its sides. Heke also had a 6-pounder cannon within the pā.[30][33]

The pā was still under construction although the northern, western and eastern sides were largely complete. Only the southern side was unfinished, consisting of little more than a fence.[16][36] The departure of some of Heke's warriors as the British approached affected the progress of the work on the pā.[37] According to historian James Belich, it is also likely that Nene's skirmishing efforts during April took manpower away from the building of the pā's defences and slowed its completion.[15][16] In terms of weaponry, in the 1840s, Māori warriors had a variety of traditional close combat weapons available to them: taiaha (striking staffs) and mere or patu (war clubs). Some also had muskets or shotguns, either acquired from the battlefield or purchased from traders.[38]

Battle edit

The British assessed Heke's position as being "very strong".[30] Despite this, Hulme was confident of success, as were his men, one going as far as to later claim to historian James Cowan that they "expected to make short work of Johnny Heke".[19][39] Hulme initially envisaged making a frontal assault, physically pulling down the palisades to gain access but Nene talked him out of this, considering that there would be heavy losses. Hulme also came to believe that artillery fire would be required to breach the palisades. He instead planned for three separate parties to make their own attacks on the pā once the Congreve rockets had been fired off. Hulme organised a party of militia to be equipped with axes, so they could breach the palisades when required. Nene's taua had no planned role; they were placed on the high ground to the east of the pā.[30][40][41]

The battle commenced on 8 May, after the British advanced to the site from Ōkaihau, marching across soggy ground and positioning themselves on the high ground to the west of the pā. The first of the three attacking parties numbered about 50 sailors and was commanded by Johnson; the second was a company of soldiers from the 58th Regiment; and the third was made up of soldiers of the 96th Regiment plus the Royal Marines. The balance of Hulme's forces was kept in reserve.[30]

At 10:00 am, the British parties began to move, bayonets fixed, to their starting positions for the attack which involved traversing the ground between the south side of the pā and Lake Ōmāpere. At the same time, the Congreve rockets were fired off but most either overshot or passed through the pā without hitting anything. One did explode within the pā but caused little damage. This was due to the faulty placement of the launcher for the Congreve rockets. Originally sited further away by Egerton, Hulme ordered it to be moved forward to within 140 metres (460 ft) of the pā.[20][30] According to Frederick Maning, a notable settler who was well connected to the Ngāpuhi, the failure of the rockets may have provided Heke's men with a morale boost, as they were convinced that this was as a result of protective rituals performed during the construction of the pā.[19]

The advancing British were exposed to gun fire from the pā as they moved forward. Then, the naval party and the soldiers of the 58th Regiment encountered Kawiti and his men, sheltering behind the breastwork on the slope behind the pā. After firing a volley of shots, the British immediately charged and engaged the Māori in hand-to-hand combat, while still under fire from the pā. After 15 minutes of fighting, Kawiti and his men withdrew and the British took shelter in the now vacated high ground. At 11:00 am, Hulme ordered the attacking parties to prepare to advance and they formed up close to the breastwork.[30][42] Then, Honi Ropiha, a Māori guide leading the British, spotted Kawiti and around 200 warriors moving behind and to the right of the British. Now alerted, the British peremptorily attacked Kawiti's force, leaving around 70 soldiers of the 58th Regiment at the breastwork, directing fire at the pā.[22][42]

Kawiti's men refrained from shooting their weapons until the British were in close proximity and then opened fire. This caused a number of casualties among the British. The fighting then reverted to combat at close quarters. Then, a number of warriors, led by Haratua, an ally of Heke, sallied out from the pā, making for the 70 soldiers that had been left at the breastwork. Just prior to this, a red flag had been raised and lowered within the pā; Cowan speculates that this was a signal to Kawiti's men. These soldiers were pushed back but by then, Kawiti's forces had been dispersed back to the bush so the remainder of the British regathered and advanced on Haratua's party. More hand-to-hand fighting ensued and the Māori withdrew to the pā.[22][42]

In the meantime, Kawiti had regathered his forces and, as Haratua and his men withdrew into Heke's pā, mounted yet another attack on the British. The exhausted British sailors and soldiers had to switch fronts and meet Kawiti's attack in one final skirmish. The Māori were driven off, taking to the bush. A quarter of the British attackers had become casualties since the commencement of battle. Acknowledging the effect of the engagement on his men, Hulme ordered a retreat. The fighting had lasted for over four hours and sporadic gunfire from the pā continued until sunset.[22][35][43]

Nene's taua of 300 warriors was not actively involved in the attack on the pā but provided cover fire as the British forces withdrew from the field. Crosby notes that this was likely to have been important in deterring Heke's men from sallying from the pā and attacking the soldiers as they cleared the battlefield of the British wounded during their withdrawal. As the British made their way back to Nene's pā at Ōkaihau, rain set in.[43][44][45]

The British casualties amounted to 13 killed and 30 to 40 wounded. Two of the wounded later died.[44][46] Māori losses were higher; around 30 killed, the majority being from Kawiti's taua. Another 50 or so were wounded.[41][46][Note 3] Kawiti himself was wounded and was fortunate to not have been killed; falling to the ground, he had been overrun by the British who had been ordered to kill any wounded warriors to prevent them reengaging in the battle.[22] Burrows arranged for the burial of the British dead, which Hulme had left behind, on the battlefield after being requested to do so by Heke.[47]

Aftermath edit

After spending a damp night at Ōkaihau with minimal food and cover, Hulme withdrew his demoralised force to Kerikeri, abandoning the prospect of any further attacks at Puketutu. Nene provided some assistance in moving the wounded and on 13 May, Hulme and the wounded left on the North Star for Auckland. In the meantime, Kawiti and his taua withdrew from Puketutu, carrying their dead and wounded, moving to Pakaraka on the way to Waiōmio, their home region. Heke also withdrew his forces from Puketutu, abandoning the pā which had served its purpose. He and his men moved to Maungakawakawa, south of Ōhaeawai. The next day, Nene's forces burnt the pā down.[43][46][48]

Hulme had estimated that around 200 of Heke and Kawiti's warriors had been killed or wounded at Puketutu;[49] however his official report did not state this number, only that their losses "must have been great".[50] FitzRoy, on receiving Hulme's report of the engagement, declared that the battle was a major victory for the British, and that Heke and Kawiti had taken 200 casualties and were "beaten and dispersed".[41] However, this was treated with scepticism by some; for example, Maning believed that only about 28 of the Māori combatants had been killed. Until he abandoned it on 9 May, Heke retained control of the battlefield following Hulme's withdrawal, and as such, Puketutu was his victory.[41][46][51]

The mutual cooperation between the respective forces of Kawiti and Heke was important to their success in the battle, an aspect not given much credit by contemporary reports at the time. Instead, Kawiti's actions, and then Haratua's, were seen as being fortuitous rather than premediated, notwithstanding the use during the battle of what are likely to have been signal flags.[41] Furthermore, the Māori realised that fighting in the open with the British was to be avoided, as evidenced by Kawiti's losses. The engagement at Puketutu was to be the only time large bodies of British troops and Māori warriors clashed over open ground. Future battles would mainly be sieges or involve bush fighting.[52] For the British, while their first attack on an inland pā was a failure, there was at least a better understanding of the environment in which their soldiers had to fight. There was also some confidence to be had in that in man-to-man fighting over open ground at least, they were at least a match for the Māori.[32][46][51]

With the British temporarily leaving the field, Nene and Heke's forces fought an engagement at nearby Te Ahuahu on 12 June; the latter was defeated and seriously wounded in the battle. This took Heke out of the campaign, leaving Kawiti and his men to bear the brunt of the future fighting. The British, now reinforced and under the command of Colonel Henry Despard, attacked Kawiti at his pā at Ōhaeawai on 1 July. Despite the pā being subject to an artillery bombardment in the days prior to the attack, the resulting battle was a defeat for the British, having incurred at least 100 casualties. Several days later, Kawiti abandoned the position which allowed Despard to enter the pā and claim success.[53][54] The final engagement of the Flagstaff War was at Kawiti's new pā at Ruapekapeka, which the British besieged from 31 December to 11 January 1846; Heke, recovered from his wounds, was present for the early stages of the siege and urged Kawiti to evacuate, which he refused to do. The pā was taken on 11 January when the British and Nene's men realised it was largely empty and entered. Kawiti and a few others were still present at the rear of the position and escaped. By this time, Nene wanted an end to the fighting in the Bay of Islands while Heke and Kawiti lacked the necessary supplies and manpower for an extended campaign. Meanwhile the new Governor of New Zealand, George Grey, also sought an end to the fighting. The three Māori rangatira agreed to lower arms and in return, Nene obtained a pardon for Heke and Kawiti from Grey thus ending the Flagstaff War.[55][56]

Current battlefield edit

The remains of Heke's pā were clearly evident up until prior to the First World War, when it was mostly cleared with earth moving equipment.[33] Cowan, visiting the site in 1919, noted that some trenches were still visible.[57] As of 2010, the site of the Battle of Puketutu[Note 4] is privately owned farmland, used for grazing livestock, about 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) from present day Ōkaihau. State Highway 1 runs past the location.[59][60]

Notes edit

Footnotes edit

- ^ Also known as the Northern War or Hōne Heke’s Rebellion.[7]

- ^ Also referred to as Te Mawhe due to its proximity to that nearby pā, and as Ōkaihau due to its proximity to the village to the northwest.[32]

- ^ Some of the dead included Kawiti's relatives, among them his son.[44]

- ^ Historian James Cowan notes that some early commentators on the Flagstaff War incorrectly referred to the site as being Ōkaihau, which was actually Nene's pā a few kilometres to the west.[58]

Citations edit

- ^ "The Treaty in Brief: Introduction". New Zealand History. Ministry for Culture & Heritage. Archived from the original on 26 April 2021. Retrieved 20 January 2023.

- ^ O'Malley 2019, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Keenan 2021, pp. 131–132.

- ^ "Origins of the Northern War". New Zealand History. Ministry for Culture & Heritage. Archived from the original on 12 January 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Belich 1998, p. 33.

- ^ Keenan 2021, p. 134.

- ^ a b "The Northern War: Introduction". New Zealand History. Ministry for Culture & Heritage. Archived from the original on 1 February 2023. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Belich 1998, pp. 36–39.

- ^ O'Malley 2019, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b Belich 1998, pp. 36–37.

- ^ a b Crosby 2015, p. 45.

- ^ Dennerly 2018, p. 65.

- ^ Crosby 2015, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Crosby 2015, p. 40.

- ^ a b Crosby 2015, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c d e f g Belich 1998, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f Crosby 2015, pp. 48–49.

- ^ a b Dennerly 2018, p. 66.

- ^ a b c d Simons 2019, p. 121.

- ^ a b Cowan 1955, p. 42.

- ^ Ryan & Parham 2002, pp. 29–31.

- ^ a b c d e Dennerly 2018, p. 68.

- ^ Crosby 2015, p. 33.

- ^ Simons 2019, p. 119.

- ^ Belich 1998, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Crosby 2015, p. 50.

- ^ Simons 2019, p. 102.

- ^ a b c Simons 2019, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Crosby 2015, pp. 50–51.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Dennerly 2018, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Moon 2001, pp. 107–108.

- ^ a b Cowan 1955, p. 41.

- ^ a b c Challis 1990, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Prickett 2016, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Keenan 2021, p. 138.

- ^ a b Cowan 1955, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Moon 2001, p. 106.

- ^ Ryan & Parham 2002, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Cowan 1955, p. 39.

- ^ Crosby 2015, p. 52.

- ^ a b c d e Belich 1998, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b c Cowan 1955, pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b c Cowan 1955, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Crosby 2015, p. 54.

- ^ O'Malley 2019, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d e Simons 2019, p. 122.

- ^ Cowan 1955, p. 47.

- ^ Crosby 2015, p. 55.

- ^ Moon 2001, p. 111.

- ^ Hulme, W. (31 May 1845). "Despatches" (PDF). New Zealand Government Gazette. No. 12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 5 February 2024.

- ^ a b Dennerly 2018, p. 69.

- ^ Belich 1998, pp. 44–45.

- ^ O'Malley 2019, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Keenan 2021, pp. 139–141.

- ^ O'Malley 2019, pp. 54–57.

- ^ Keenan 2021, pp. 143–144.

- ^ Cowan 1955, p. 48.

- ^ Cowan 1955, p. 38.

- ^ Green 2010, p. 34.

- ^ Finlay 1998, pp. 16–17.

References edit

- Belich, James (1998) [1986]. The New Zealand Wars and the Victorian Interpretation of Racial Conflict. Auckland: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-027504-9.

- Challis, Aidan J. (1990). "The location of Heke's Pa, Te Kahika, Okaihau, New Zealand: A Field Analysis". New Zealand Journal of Archaeology. 12: 5–27. ISSN 0110-540X.

- Cowan, James (1955) [1922]. The New Zealand Wars: A History of the Māori Campaigns and the Pioneering Period: Volume I (1845–64). Wellington: R.E. Owen. OCLC 715908103.

- Crosby, Ron (2015). Kūpapa: The Bitter Legacy of Māori Alliances with the Crown. Auckland: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-357311-1.

- Dennerly, Peter (2018). "The Navy in the Northern War: New Zealand 1845–46". In Crawford, John; McGibbon, Ian (eds.). Tutu Te Puehu: New Perspectives on the New Zealand Wars. Wellington: Steele Roberts Aotearoa. pp. 57–84. ISBN 978-0-947493-72-1.

- Finlay, Neil (1998). Sacred Soil: Images and Stories of the New Zealand Wars. Auckland: Random House New Zealand. ISBN 978-1-86-941357-6.

- Green, David (2010). Battlefields of the New Zealand Wars: A Visitor's Guide. Auckland: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-320418-3.

- Keenan, Danny (2021) [2009]. Wars Without End: New Zealand's Land Wars – A Māori Perspective. Auckland: Penguin Random House New Zealand. ISBN 978-0-14-377493-8.

- Moon, Paul (2001). Hone Heke Nga Puhi Warrior. Auckland: David Ling Publishing. ISBN 978-0-90-899076-4.

- O'Malley, Vincent (2019). The New Zealand Wars: Nga Pakanga O Aotearoa. Wellington: Bridget Williams Books. ISBN 978-1-988545-99-8.

- Prickett, Nigel (2016). Fortifications of the New Zealand Wars (PDF). Wellington: Department of Conservation. ISBN 978-0-478-15070-4.

- Ryan, Tim; Parham, Bill (2002). The Colonial New Zealand Wars. Wellington: Grantham House Publishing. ISBN 978-1-86934-082-7.

- Simons, Cliff (2019). Soldiers, Scouts & Spies: A Military History of the New Zealand Wars 1845–1864. Auckland, New Zealand: Massey University Press. ISBN 978-0-9951095-7-5.