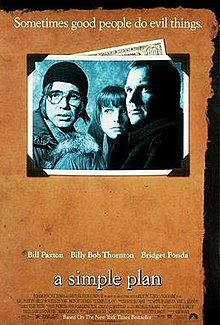

A Simple Plan is a 1998 American neo-noir crime thriller film directed by Sam Raimi and written by Scott B. Smith, based on Smith's 1993 novel of the same name. The film stars Bill Paxton, Billy Bob Thornton, and Bridget Fonda. Set in rural Minnesota, the story follows brothers Hank (Paxton) and Jacob Mitchell (Thornton), who, along with Jacob's friend Lou (Brent Briscoe), discover a crashed plane containing $4.4 million in cash. The three men and Hank's wife Sarah (Fonda) go to great lengths to keep the money a secret but begin to doubt each other's trust, resulting in lies, deceit and murder.

| A Simple Plan | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sam Raimi |

| Screenplay by | Scott B. Smith |

| Based on | A Simple Plan by Scott B. Smith |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Alar Kivilo |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Danny Elfman |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 121 minutes |

| Countries | United States United Kingdom Germany France Japan |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $17 million[3][4][5] |

| Box office | $16.3 million[3][6] |

Development of the film began in 1993 before the novel was published. Mike Nichols purchased the film rights, and the project was picked up by Savoy Pictures. After Nichols stepped down, the film adaptation became mired in development hell, with Ben Stiller and John Dahl turning down opportunities to direct it. After Savoy closed in November 1997, the project was sold to Paramount Pictures. John Boorman was hired to direct, but scheduling conflicts led to his replacement by Raimi. An international co-production between the United States, United Kingdom, Germany, France and Japan, the film was financed by Mutual Film Company, its investors and Newmarket Capital Group, which allocated a budget of $17 million. Principal photography began in January 1998 and concluded in March after 55 days of filming in Wisconsin and Minnesota. The score was produced and composed by Danny Elfman.

A Simple Plan premiered at the 1998 Toronto International Film Festival, where it was met with critical acclaim. The film's appearance at the festival preceded a limited release in the United States on December 11, 1998, followed by a general release in North America on January 22, 1999. It underperformed at the North American box office, grossing $16.3 million, but was critically acclaimed, with reviewers praising various aspects of the film's production, including the storytelling, performances and Raimi's direction. A Simple Plan earned multiple awards and nominations, among them two Academy Award nominations, one for Best Supporting Actor (Thornton) and one for Best Adapted Screenplay (Smith).

Plot edit

Hank Mitchell and his pregnant wife Sarah live in rural Wright County, Minnesota. One of the town's few college graduates, Hank works as a bookkeeper at a feed mill, while Sarah is a librarian. Hank; his older brother Jacob, who has learning difficulties; and their friend Lou Chambers chase a fox into the woods, and stumble upon a crashed airplane. Hank decides to look inside the plane where he discovers a dead pilot and a bag containing $4.4 million in $100 bills. He suggests turning the money in, but Lou and Jacob persuade him not to. Hank then proposes that he keep the money safe at his house until the end of winter when the snow will melt and the plane will be found. At that point, if no one talks about missing money, they will take their share and move away.

Sheriff Carl Jenkins drives by the area and notices the three men after they've hidden the money in Jacob's pickup truck. At Lou's suggestion, Jacob attempts to avoid suspicion by mentioning hearing a plane nearby. Hank becomes worried but they return to their truck. After Carl leaves, the three men decide to keep the money a secret, but Hank breaks the pact when he reveals the discovery to Sarah.

Sarah suggests that Hank return a small portion of the money to the plane to avoid suspicion from local authorities. She insists that he should go alone, but Hank takes Jacob with him. Hank walks through the woods to the plane while Jacob waits at the car pretending to change the tire. Elderly farmer Dwight Stephanson approaches Jacob on a snowmobile and asks him if he came across a fox that ran off with a chicken. Jacob, thinking that their cover is blown, bludgeons Dwight. Thinking Dwight is dead, Hank tells Jacob they need to split up and meet later whilst he moves the body. But Dwight regains consciousness, so Hank suffocates him. He then uses the snowmobile to drive the body off a bridge, making the murder resemble an accidental death.

While searching newspaper clippings at the library, Sarah finds out that the money was a ransom for a kidnapped heiress from Michigan, who was abducted by two brothers, Stephen and Vernon Bokovsky. Sarah surmises that the dead pilot was one of the brothers, as the ransom was delivered, but the whereabouts of the two brothers remain unknown.

The following night, Lou drunkenly demands his portion of the money from Hank, because he is broke and has spent recklessly since the discovery. When Hank refuses, Lou threatens to go to the authorities, having learned from Jacob about Dwight's murder. Hank lies to Lou, telling him that the money is not inside his house. He gives him $40 to appease him and calms him down by telling him that they are in this together.

After giving birth to their daughter, Amanda, Sarah advises Hank to frame Lou for Dwight's murder by getting him drunk, tricking him into falsely confessing to the killing and recording the confession. The plan works, although Jacob is dismayed and reluctant to betray his friend. Lou grows enraged when he realizes that they have conspired against him, and he pulls a shotgun on Hank. Jacob then grabs his hunting rifle and, after a tense standoff, kills Lou to save Hank. Hank then tries to calm Lou's wife Nancy, who gets another gun and shoots at Hank, who in turn kills her with Lou's shotgun. Hank stages the scene to make it look like Lou shot Nancy and was about to shoot him. He and Jacob tell the police this story, and successfully avoid arrest and suspicion.

Because Jacob mentioned hearing a plane in the woods, Carl asks the brothers to assist FBI agent Neil Baxter in a search for the missing aircraft. Hank and Jacob meet with Baxter and Carl at the police station. Sarah is immediately skeptical of Baxter, suspecting he is actually Vernon Bokovsky, posing as an FBI agent to recover the money for himself. When she discovers this to be true, she calls to warn Hank, who steals a revolver and a handful of bullets from Carl's office. The four men head into the woods and split up. When he finds the plane, Baxter kills Carl, and forces Hank to retrieve the money from the plane. Hank manages to distract Baxter with the small amount of money he had returned to the plane before then shooting and killing Baxter.

Hank starts to concoct another story to tell the authorities, but Jacob tells him that he does not want to live with the memories of what they have done, asking Hank to kill him and frame Baxter for it. When Hank refuses, he threatens to commit suicide, which would implicate them both in the conspiracy. After weighing the decision, a heartbroken Hank kills Jacob with Baxter's pistol. At the police station, Hank tells his rehearsed story to real FBI agents. He is cleared of any wrongdoing and is told that many of the serial numbers on the bills used in the ransom were written down to track the cash, so the bills making up that cash could not in any case realistically be spent without the individual eventually being caught. Hank returns home and burns it all, leaving Sarah distraught. In a closing narration, Hank reflects on his losses. Although he tries to move on with his life, the murders constantly haunt him.

Cast edit

- Bill Paxton as Hank Mitchell

- Billy Bob Thornton as Jacob Mitchell

- Bridget Fonda as Sarah Mitchell

- Brent Briscoe as Lou Chambers

- Gary Cole as Vernon Bokovsky / FBI Agent Neil Baxter

- Jack Walsh as Tom Butler

- Chelcie Ross as Sheriff Carl Jenkins

- Becky Ann Baker as Nancy Chambers

Production edit

Development edit

After Scott B. Smith had published a short story for The New Yorker, the magazine's fiction editor learned of his then-unpublished novel A Simple Plan before reading it and forwarding it to an agent. Shortly thereafter, Smith learned that Mike Nichols was interested in purchasing the film rights.[7] Nichols spent a weekend reading the book, before contacting Smith's agent and finalizing a deal the following Monday morning. Nichols purchased the rights for his production company Icarus Productions[8] for $250,000, with an additional $750,000 to come later from a studio interested in pursuing the project.[9] Smith's manuscript of A Simple Plan was optioned for development at an independent film studio, Savoy Pictures. Nichols later stepped down from the project, due to scheduling conflicts with a planned film adaptation of All the Pretty Horses.[10]

After learning of A Simple Plan from Nichols, Ben Stiller joined the project[10] and signed a two-picture directing deal with Savoy.[11] He spent nine months working on the script with Smith. During preproduction, Stiller had a falling out with Savoy over budget disputes.[10] Unable to secure financing from another studio, Stiller left the film.[12]

In January 1995, John Dahl was announced as director, with Nicolas Cage set to appear in a starring role, and filming likely to start during the following summer in the southern hemisphere or in Canada during the following winter.[12][13] In November 1995, following a series of box office failures, Savoy announced that it was retreating from the film industry.[14] The studio was later acquired by Silver King Broadcasting/Home Shopping Network, whose chairman, Barry Diller, put A Simple Plan up for sale.[10] This resulted in both Dahl and Cage leaving the production.[10][12]

The project was purchased by Paramount Pictures, where producer Scott Rudin hired John Boorman to direct the film. Boorman cast Bill Paxton and Billy Bob Thornton in the respective leading roles of Hank and Jacob Mitchell.[15] The film marked Paxton and Thornton's second on-screen collaboration after One False Move (1992).[16] Paxton learned of the novel A Simple Plan from his father five years before securing the role of Hank. He stated, "... for five years, there was a whole list of actors and directors who kind of marched through it. Billy Bob and I were set to do these roles in 1997, and then it fell apart. That was the cruelest twist for an actor, to get a part you dreamed you'd get and then they decide to scrap the whole thing."[16]

Boorman took part in location scouting, and filming was set to begin during the first week of January 1998.[12] When a second investor left the project, Paramount refused to fully finance the $17 million production itself.[12][15] Although Boorman was able to secure financing, the studio feared that filming would not be finished before the end of winter.[12] Boorman ran into scheduling conflicts, and left the film.[12] Paramount then hired Sam Raimi,[15] who saw the film as an opportunity to direct a character-driven story that differed from his earlier works, which were highly stylized or dependent on intricate camera movements.[7] Raimi did not have time to scout locations due to studio constraints. He relied on the previous areas visited during Boorman's involvement.[12] Rudin considered casting Anne Heche as Hank's wife Sarah Mitchell.[17] In December 1997, it was announced that Bridget Fonda had secured the role. The film marks her second collaboration with Raimi after Army of Darkness (1992).[5]

The film was co-financed by Mutual Film Company and Newmarket Capital Group[4] as part of a joint venture that was formed by the two studios.[18] Mutual's international partners—the United Kingdom's BBC, Germany's Tele-München, Japan's Toho-Towa/Marubeni and France's UGC-PH—also financed the production in exchange for distribution rights in their respective territories and equity stakes on the film on a worldwide basis.[19] Paramount acquired the North American distribution rights.[5]

Writing edit

Ben [Stiller] really taught me how to write a script. I don't know that he ever explicitly said it, but by imagining the script as a verbal description of a movie, the movie that I wanted the book to be. That's very simple, but it really was the key to everything for me—just imagining what was on the page. I was shortchanging the visual in my script, concentrating on dialogue, which I imagine is a very common first-time screenwriter's mistake, and to suddenly just do it visually opened up everything for me.

—Smith on writing the screenplay.[20]

The original script that Smith had written for Nichols was 256 pages long, the equivalent of a four-and-a-half hour film. Smith kept Nichols's suggestion of having the story take place in Minnesota, rather than in Ohio, where the book is set.[12] The Minnesota Film Board joined the project and remained involved throughout principal photography.[12] After the novel was published, Nichols left the project during the script's early draft stages.[7] When Stiller became involved, he and Smith spent nine months rewriting the screenplay.[7]

For the adaptation, certain visual changes were made from the 335-page novel. Smith explained that one change involved the discovery of the crashed plane. His script had Lou Chambers "throwing [a] snowball to uncover the plane ... In the book, they're just walking and they find it."[7] Rudin wanted to change the focus of the story to Hank and Jacob, and ordered Smith to shorten the screenplay to 120 pages. Smith explained, "I had to work to make Hank a more rational character, less evil."[7] The shortening of the script also resulted in the character of Sarah having a smaller role, and Jacob's involvement being much larger than in the book. After Billy Bob Thornton was cast as Jacob, Smith omitted the character's overweight appearance from the novel.[7] Smith described the film adaptation as being less violent than the book, explaining that it was Raimi's decision "to be more restrained [and] bring out the characters."[15]

Filming edit

Principal photography edit

Filming was scheduled to begin in Delano, Minnesota, but due to climatic changes as the result of El Niño, the production was forced to temporarily relocate to northern Wisconsin to find the snow levels described in the script.[21] Principal photography began on January 5, 1998.[22] The film marked production designer Patrizia von Brandenstein's second collaboration with Raimi, after The Quick and the Dead (1995). She found the weather difficult during filming, as she had to await good conditions to complete the necessary exterior work. Describing the overall look of the film, she stated, "We created a muted black-and-white color scheme to suggest a morality tale, the choices given between right and wrong."[21] The production began shooting in Ashland and Saxon, Wisconsin, where most of the film's exterior shots were filmed.[22] An actual plane, with one side cut open, was one of two planes used to depict the crashed aircraft.[22]

The production returned to Minnesota, where it was plagued by a lack of snow.[23] To solve this problem, the filmmakers assembled a special effects team to create a combination of real snow and fake synthetic snow that was made from shaved ice.[23]: 2 The home of Lou Chambers and his wife Nancy was filmed in an abandoned house in Delano,[22] which cinematographer Alar Kivilo described as "a very difficult [filming] location with very low ceilings and no heating".[23] Brandenstein and the art department were tasked with designing the set inside the home.[23][24]

The interior of the crashed plane was filmed on a soundstage. A second plane, designed to have frosted windows, was attached to a gimbal, about five feet off the ground. To match the interior with footage shot in Wisconsin, the art department built a set with real trees and a painted backdrop.[24] To depict Hank being attacked by a flock of crows inside the plane, puppets were used to attack Paxton as he appeared on screen, while two live crows were used to attack an animatronic replica of the actor.[24] A separate soundstage was used to create two sets depicting the interiors of the Mitchell home, where Hank and his wife Sarah (Fonda) reside. The first set was the main floor and exterior entrance way, and the second was created for the upstairs bedrooms.[24] Principal photography concluded on March 13, 1998, after 55 days of filming.[8][22]

Cinematography edit

This is a change of pace for me because the film is not about shots, but the performance within the frame. I wanted the camera work to be invisible and just allow the actors to tell this very thrilling story.

—Sam Raimi (director)[25]

Director of photography Alar Kivilo stated that, upon reading the script, his first approach to making the film "was to make the look simple, allowing the characters to tell the story."[24] He was influenced by the visuals of In Cold Blood (1967), the work of photographer Robert Frank[24] and photographs taken during location scouting in Delano, Minnesota.[23] Kivilo originally wanted to shoot the film in widescreen using the anamorphic format, but decided against it due to the lack of lenses available and the film's restricted budget.[23] He shot the film using Panavision Platinum cameras with the company's Primo series of prime lenses.[23] He used Eastman Kodak 5246 250ASA Vision film stock for all of the daylight scenes and tungsten-balanced 5279 Vision 500T film stock for the night scenes.[23]

Despite the intense weather conditions, Kivilo believed that the overcast skies created a "gray, somber, stark look."[24] He also chose not to use any lighting for daytime exterior scenes.[23] For exterior scenes shot during sunnier filming days, computer-generated imagery (CGI) was used to re-create the overcast skies[23] and counter any inconsistencies caused by the falling snow.[24] In depicting the shootout in Lou's home, Kivilo's intent was to "keep things quite sketchy in the lighting and not be clear about exactly what was happening." The camera department lit a China ball from the ceiling to depict a dimly lit kitchen light that would reveal Nancy holding a shotgun.[23] Flash photography guns were used to depict the muzzle flashes during the shootouts.[23]

Music edit

The score was produced and composed by Danny Elfman, who was drawn to the film after learning of Raimi's involvement; the film marks his third collaboration with the director. The instruments included alto and bass flutes, re-tuned pianos and banjos, zithers, and hand drums.[26] The soundtrack album, titled A Simple Plan: Music from the Motion Picture Soundtrack, was released on January 26, 1999.[27] AllMusic's William Ruhlmann wrote, "There are occasional moments that suggest the composer's more characteristic approach, but his writing is in the service of a smaller, if still intense cinematic subjects, and it is appropriately restrained."[27]

Track listing edit

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Main Title" | 4:44 |

| 2. | "The Moon" | 0:57 |

| 3. | "A Change of Heart" | 1:07 |

| 4. | "The Farm" | 1:31 |

| 5. | "Betrayal Part 1" | 3:16 |

| 6. | "The Badge" | 1:08 |

| 7. | "Stop It" | 1:40 |

| 8. | "Tracks in the Snow" | 4:37 |

| 9. | "Death" | 4:54 |

| 10. | "Burning $" | 1:50 |

| 11. | "End Credits" | 5:10 |

| 12. | "Preachin' the Blues (The Imperial Crowns)" | 3:42 |

| 13. | "So Sleepless You (Jolene)" | 4:21 |

| 14. | "Deliver Me (Tina and the B Sides)" | 4:50 |

| Total length: | 43:47 | |

Release edit

A Simple Plan premiered at the 23rd Toronto International Film Festival on September 11, 1998.[29] On December 11, 1998, the film opened in limited release at 31 theaters, and grossed $390,563 in its first week, with an average of $12,598 per theater.[6] More theaters were added during the limited run, and on January 22, 1999, the film officially entered wide release by screening in 660 theaters across North America.[30] The film ended its North American theatrical run on May 14, 1999, having grossed $16,316,273, below its estimated production budget of $17 million.[3][6] The film was released on VHS and DVD on June 22, 1999, by Paramount Home Entertainment.[31]

Reception edit

Critical response edit

On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, 90% of 73 reviews of the film were positive, with an average rating of 8.3/10. The website's consensus calls the film "A riveting crime thriller full of emotional tension."[32] Another review aggregator, Metacritic, assigned the film a weighted average score of 82 out of 100, based on 28 reviews from mainstream critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[33]

Reviewing the film during the Toronto International Film Festival, Glen Lovell of Variety compared it to Fargo (1996), writing, "The key differences are in emphasis and tone: Fargo is deadpan noir; A Simple Plan...is a more robust Midwestern Gothic that owes as much to Poe as Chandler."[34] In an "early review" of the film prior to its limited release, Roger Ebert and his colleague, Gene Siskel, gave the film a "Two Thumbs Up" rating on their syndicated television program Siskel and Ebert at the Movies.[35] In a later episode, Ebert ranked A Simple Plan at number four on his list of the "Best Films of 1998".[36] Siskel, writing for the Chicago Tribune, said that the film was "an exceedingly well-directed genre picture by [Raimi] ... [who] does an excellent job of presaging the lethal violence that follows. From his very first images we know that bodies are going to start to pile up."[37] Ebert also named Bill Paxton as his suggested pick for the Best Actor nomination at the 1999 Academy Awards.[38]

John Simon of the National Review wrote, "the dialogue and characterization are rich in detail, and the constant surprises do not, for the most part strain credibility".[39]

Online film critic James Berardinelli praised the acting, but commended Thornton's performance as being "the most striking that A Simple Plan has to offer."[40] After Paxton's death in February 2017, Matt Zoller Seitz of RogerEbert.com cited the actor's performance as Hank to be the best in his career, stating that "The film might constitute Paxton's most sorrowful performance as well as his most frightening ... an outwardly ordinary man who has no idea what kind of evil he's capable of."[41]

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly described the film as being "lean, elegant, and emotionally complex—a marvel of backwoods classicism."[42] Janet Maslin of The New York Times called it a "quietly devastating thriller directed by [Raimi] ... who makes a flawless segue into mainstream storytelling."[43] Edward Guthmann of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, "for Raimi, whose mastery of visual effects has driven all of his previous films, A Simple Plan marks a tremendously successful break from the past. He's drawn lovely, complex performances from Paxton and Thornton and proven that he can work effectively—and movingly—in a minor emotional key."[44]

In a negative review, Richard Schickel of Time stated, "There's neither intricacy nor surprise in the narrative, and these dopes are tedious, witless company."[45] Schlomo Schwartzberg of Boxoffice felt that the film "clutters up the story with unnecessary acts of violence and murder, and mainly stays on the surface, offering little more than cheap jolts of melodrama."[46]

In an interview with Empire Magazine, Sam Raimi gives his opinion about the lukewarm box-office reception and the Fargo’s comparisons:

“I don't think it was overshadowed by [Fargo]. It just didn't get a big release. Maybe people didn't like it as much as they could have.“[47]

Accolades edit

Notes edit

- ^ Tied with William H. Macy for A Civil Action, Pleasantville and Psycho.

- ^ Tied with Thursday.

- ^ Tied with Bill Murray for Rushmore and Wild Things.

References edit

- ^ a b Cox, Dan (20 December 1997). "Fonda has 'A Simple Plan'". Variety. Retrieved 9 November 2021.

- ^ "Mutual Film taps Pickering". Variety. 4 May 1998. Retrieved 10 November 2021.

- ^ a b c "A Simple Plan – Box Office Data, DVD and Blu-ray Sales, Movie News, Cast and Crew Information". The Numbers. Nash Information Services, LLC. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Molley, Claire (February 2010). "Memento and Independent Cinema: A Seductive Business". Memento. United Kingdom: Edinburgh University Press, Ltd. p. 15. ISBN 978-0748637720.

- ^ a b c Cox, Dan (December 20, 1997). "Fonda has 'A Simple Plan'". Variety. Variety. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c "A Simple Plan (1998) – Weekend Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g Anderson, Jeffrey M. (November 18, 1998). "Interview with Scott B. Smith". Combustible Celluloid. Jeffrey M. Anderson. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b "Simple Plan, A (1998) – Misc Notes". Turner Classic Movies. Turner Entertainment Networks, Inc. Archived from the original on 2015-02-04. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Elias, Thomas D. (January 4, 1993). "Entertainment World Proves Entertaining". Deseret News. Deseret News. Retrieved February 24, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Ascher-Walsh, Rebecca (April 11, 1997). "Fighting Words". Entertainment Weekly. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Producer Has Plans For South Florida". Orlando Sentinel. Orlando Sentinel. August 5, 1994. Archived from the original on 2015-07-14. Retrieved July 14, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Strickler, Jeff (December 5, 1998). "Making 'A Simple Plan' became a difficult task". Star Tribune. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Sluggish Savoy Revs Up Production Under Fried". Variety. January 22, 1995. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Company Town Annex – Los Angeles Times". Los Angeles Times. November 15, 1995. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d Fetzer, Bret (October 9, 2006). "The Simple Complex". Seattle Weekly. Seattle Weekly. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger (December 15, 1998). "Bill Paxton doesn't monkey around". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 7, 2015.

- ^ Pearlman, Cindy (October 3, 1997). "Entertainment news for October 3, 1997". Entertainment Weekly. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved February 20, 2015.

- ^ Carver, Benedict (May 18, 1998). "Capital building". Variety. Variety. Retrieved February 9, 2015.

- ^ Hindes, Andrew (February 4, 1998). "Mutual agreement". Variety. Variety. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ^ David S. Cohen (February 2008). "Chance, Fate, and Homework: A Simple Plan: Scott Smith". Screen Plays. United States: HarperCollins. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-0-06-143157-9.

- ^ a b "A Simple Plan – Movie Production Notes". CinemaReview.com. CinemaReview. Archived from the original on 2015-02-04. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Calhoun, John (January 1, 1999). "Snow blind: DP Alar Kivilo witnesses A Simple Plan gone awry". LiveDesign. Penton. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Holben, Jay (December 1998). "The Root of All Evil". American Cinematographer. 79 (12). United States: American Society of Cinematographers. Archived from the original on September 10, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Rogers, Pauline. "Alar Kivilo". IATSE Local 600. International Cinematographers Guild. Retrieved February 6, 2015.

- ^ "A Simple Plan – Movie Production Notes". CinemaReview.com. CinemaReview. Archived from the original on 2015-02-04. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "Film Music on the Web CD Reviews March 1999: Interview with Danny Elfman, composer". Film Music on the Web. Cinemedia Promotions. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ a b "A Simple Plan [Original Score] – Danny Elfman". AllMusic. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "A Simple Plan (Music from the Motion Picture Soundtrack)". Soundtrack.net.

- ^ "23rd Toronto International Film Festival Coverage". Retrieved October 11, 2013.

- ^ "A Simple Plan (1998) – Weekend Box Office Results – Box Office Mojo". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "VHS: A Simple Plan (VHS)". Tower Video. Tower Records. Archived from the original on 2015-02-04. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "A Simple Plan". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. 12 September 1998. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ^ "A Simple Plan Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Lovell, Glenn (September 15, 1998). "A Simple Plan". Variety. Variety. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert (December 5, 1998). Siskel and Ebert and the Movies.

- ^ Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert (January 2, 1999). Siskel and Ebert and the Movies.

- ^ Siskel, Gene (February 5, 1999). "The story of a young blind man". Chicago Tribune. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "Siskel & Ebert - Memo the Academy (1999)". YouTube.

- ^ Simon, John (2005). John Simon on Film: Criticism 1982-2001. Applause Books. p. 581.

- ^ Berardinelli, James. "A Simple Plan". Reelviews. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ "The Consummate Everyman: Goodbye to Bill Paxton". RogerEbert.com. Ebert Digital LLC. February 27, 2017. Retrieved February 28, 2017.

- ^ Glieberman, Owen (December 11, 1998). "A Simple Plan". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (11 December 1998). "Movie Review - A Simple Plan - FILM REVIEW; A Frozen Setting Frames a Chilling Tale". The New York Times. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Guthmann, Edward (December 11, 1998). "Cold, 'Simple' Truths / Taut, nuanced tale of greed". San Francisco Chronicle. San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Schickel, Richard (December 14, 1998). "Cinema: Cold Comfort". Time. Vol. 152, no. 24. United States: Time.

- ^ Schwartzberg, Shlomo (December 11, 1998). "A Simple Plan". BoxOffice. BOXOFFICE Media, LLC. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ^ Hewitt, Chris (2023). "In Conversation with Sam Raimi". Empire.

- ^ "The 71st Academy Awards (1999) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org. Retrieved 19 November 2011.

- ^ "BSFC Winners: 1990s". Boston Society of Film Critics. 27 July 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1988-2013 Award Winner Archives". Chicago Film Critics Association. January 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2021.

- ^ "The BFCA Critics' Choice Awards :: 1998". Broadcast Film Critics Association. Archived from the original on December 12, 2008.

- ^ "A Simple Plan – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Previous Sierra Award Winners". lvfcs.org. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "The 24th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "1996 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. 19 December 2009. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ^ "3rd Annual Film Awards (1998)". Online Film & Television Association. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "1998 Awards (2nd Annual)". Online Film Critics Society. 3 January 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2021.

- ^ "International Press Academy website – 1999 3rd Annual SATELLITE Awards". Archived from the original on 1 February 2008.

- ^ "Past Saturn Awards". Saturn Awards.org. Archived from the original on September 14, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2008.

- ^ "The 5th Annual Screen Actors Guild Awards: Nominees and Recipients". Screen Actors Guild. 1999. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "1998 SEFA Awards". sefca.net. Retrieved May 15, 2021.

- ^ "Past Scripter Awards". USC Scripter Award. Retrieved November 8, 2021.

- ^ "WGA Awards: Previous Nominees and Winners". Writers Guild of America Award. 1999. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 16 September 2016.