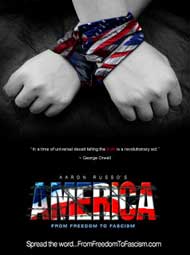

America: Freedom to Fascism is a 2006 American film by filmmaker and activist Aaron Russo, covering a variety of subjects that Russo contends are detrimental to Americans. Topics include the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the income tax, Federal Reserve System, national ID cards (REAL ID Act), human-implanted RFID tags, Diebold electronic voting machines,[1] globalization, Big Brother, taser weapons abuse, and the use of terrorism by the government as a means to diminish the citizens' rights.

| America: Freedom to Fascism | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Aaron Russo |

| Written by | Aaron Russo |

| Produced by | Aaron Russo Richard Whitley |

| Starring | Katherine Albrecht Joe Banister Dave Champion Vernice Kuglin Rep. Ron Paul Aaron Russo Irwin Schiff |

| Music by | David Benoit |

| Distributed by | Cinema Libre Studio |

Release date | July 28, 2006 |

Running time | 95 minutes Director's Cut: 111 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

The film has been criticized for its promotion of conspiracy theories, its copious factual errors, and its repeated misrepresentations of the individuals and views it purports to criticize.

Federal Reserve System issues and interviews in the film edit

The film examines the genesis and functions of the Federal Reserve System. The film asserts that the Federal Reserve System is a system of privately held, for profit corporations, not a government agency, and that the Fed was commissioned to print fiat money on behalf of the federal government, at a fee ultimately paid for by the personal income tax (through service on bond interest). The film also refers to the fact that the United States dollar is not backed by gold, and states that this means the dollar has no real backing other than future income tax payments. Consequently, the film states that Federal Reserve Notes represent debt instead of wealth.

The film argues that the Federal Reserve System manipulates what is sometimes referred to as the business cycle of economic expansion and retraction by putting new notes into circulation to increase the ease of obtaining credit, which devalues the currency, then compounds inflation by increasing interest (prime) rates. The movie argues that this manipulation is responsible for a 96% devaluation of American currency, since it was made possible to increasingly sever the link with gold backing by the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. The film says that this process of creating new money and adding it to the money supply is known as debasement and is a cause of inflation. In this way, the film concludes that the Federal Reserve System simultaneously controls the supply of money and its value.

The central thesis of the film may be that this monetary policy is the strongest form of governance that has ever existed, and is central to the unconstitutional, global power ambitions of the interests that supposedly control the Federal Reserve System.

The film also asserts that the private interests are controlling the Federal Reserve System, and have been for generations. The film proposes that most Americans are kept ignorant of how the Federal Reserve operates through actions of corrupt politicians and an increasingly centralized media. By using what the film calls legalistic and economic "mumbo-jumbo” terms such as 'monetizing the debt' or ‘adjusting monetary policy for increased fluidity of credit’, these interests, according to the film, conceal the true actions of the Fed behind veils of legitimacy. Interviews are conducted with several organizations and elected legislators who support these views.

An argument made in the film is that there is no reason why the Federal Reserve System should have a monopoly on the U.S. money supply. The film asserts that "America got along just fine before the Federal Reserve came into existence." This leads the film to the question of why the Federal Reserve System was created.

The film contends that the U.S. Congress has no control or oversight over the Fed, and hence has no control over the value of U.S. money. The film argues that Congressional control over the value of money is required by Article 1, Section 8 of the United States Constitution. The phrase in question (clause 5) states that the United States Congress shall have the power "To coin Money, regulate the Value thereof, and of foreign Coin..."

The film includes a call to action to abolish the Federal Reserve. In 2007, The Boston Globe stated that Congressman Ron Paul, "says he doesn't agree with all the film's arguments, but he says the film had 'a huge impact' on the support his campaign is drawing",[2] a reference to Paul's presidential bid in 2007 and 2008.

Federal income tax issues and interviews in the film edit

Through interviews with various individuals including former IRS agents, Russo sets forth the tax protester argument that, "there is no law requiring an income tax", and that the personal income tax is illegally enforced to support the activities of the Federal Reserve System.

One of the listed stars of the film, Irwin Schiff, was sentenced on February 24, 2006 to 13 years and 7 months in prison for tax evasion and ordered to pay over $4.2 million in restitution.[3] In pre-sentencing documents filed with the court, Schiff's lawyers had argued that he had a mental disorder related to his beliefs about taxation.[4] Initially, the film portrays Schiff as a tax expert, though his qualifications and those of many other individuals in the film are not mentioned. Later in the film, Russo reveals that Schiff has been imprisoned.

Schiff appears in the film for another reason as well. The filmmaker lampoons Judge Kent Dawson's reaction to Schiff's defense. The film alleges that the judge "denied Irwin the ability to prove to a jury that there was no law requiring Americans to file an income tax return. He denied Irwin the right to attempt to prove to a jury there was no law ... by stating, 'I will not allow the law in my courtroom.'" At 0:48:28 of the film, Russo introduces the judge and his statement.

Under the U.S. legal system, the general rule is that neither side in a civil or criminal case is allowed to try to prove to the jury what the law is. For example, in a murder case the defendant is not generally allowed to persuade the jury that there is no law against murder, or to try to interpret the law for the jury. Likewise, the prosecution is not allowed to try to persuade the jury about what the law is, or how it should be interpreted. Disagreements about what the law is; are argued by both sides before the judge, who then makes a ruling. Prior to jury deliberations, the judge, and only the judge, instructs the jury on the law.[5]

Another listed star, Vernice Kuglin, was acquitted in her criminal trial for tax evasion in August 2003.[6] This means she was not found guilty of a willful intent to evade income taxes. (A conviction for tax evasion requires, among other things, proof by the government that the defendant engaged in one or more affirmative acts of misleading the government or of hiding income.) Kuglin's acquittal did not relieve her of liability for the taxes.[7] Kuglin entered a settlement with the government in 2004 in which she agreed to pay over $500,000 in taxes and penalties.[8] On April 30, 2007, the Memphis Daily News reported that Kuglin's Federal tax problems continued with the filing of a notice of Federal tax lien in the amount of $188,025. The Memphis newspaper also stated that Kuglin has "given up her fight against paying taxes, according to a Sept. 10, 2004, Commercial Appeal story."[9]

The preview clip for the film includes assertions contradicted by official government publications regarding the activities and nature of such institutions as the Internal Revenue Service and the Federal Reserve System.[10]

Constitutional arguments edit

Fifth Amendment edit

Russo's argument using the Fifth Amendment goes as follows:

- Premise 1: The government can criminally prosecute someone and put one in jail for information one puts on one's 1040 tax form.

- Premise 2: The fifth amendment says no one can be compelled to incriminate oneself.

- Conclusion: Since filing a 1040 incriminates oneself, filing a 1040 therefore violates one's fifth amendment rights.

Though the second premise is not completely correct, the main source of error lies in the first premise. If one truthfully reports the amount of one's income, one does not incriminate oneself in the commission of a crime.[11][12] However, falsely reporting one's income is itself the commission of a crime. Put another way, the fifth amendment protects one from incriminating oneself if testifying truthfully will incriminate oneself in the commission of a crime. It does not offer a provision for lying.[13]

The fifth amendment does, however, allow oneself to avoid disclosing the source of the income if doing so would incriminate oneself in the commission of a crime.[14] While that may be the case, a person is still required to report the amount of all income on his or her federal tax return.

Sixteenth Amendment edit

The film refers to both article 1 section 8 of the U.S. Constitution, which grants Congress the authority to impose taxes, and disputes the legitimacy of the Sixteenth Amendment (see Tax protester Sixteenth Amendment arguments), which removes any apportionment requirement.

edit

Some of the premises of the film include:

- The Federal Reserve System is unconstitutional and has maxed out the national debt and bankrupted the United States government.

- Federal income taxes were imposed in response to, or as part of, the plan implementing the Federal Reserve System.

- Federal income taxes are unconstitutional or otherwise legally invalid.

- The use of the Federal income tax to counter the economic effects of the Federal Reserve System is futile.

The filmmaker's personal views on taxes edit

As of late July 2006, Aaron Russo's biography on his website for the film stated: "The film is an exposé of the Internal Revenue Service, and proves conclusively there is no law requiring an American citizen to pay a direct unapportioned Tax on their labor."[15][16]

The New York Times article of July 31, 2006, states that when Russo asked IRS spokesman Anthony Burke for the law requiring payment of income taxes on wages and was provided a link to various documents including title 26 of the United States Code (the Internal Revenue Code), filmmaker Russo denied that title 26 was the law, contending that it consisted only of IRS "regulations" and had not been enacted by Congress. The article reports that in an interview in late July 2006, Russo claimed he was confident on this point. In the United States, statutes are enacted by Congress, and regulations are promulgated by the executive branch of government to implement the statutes. Statutes are found in the United States Code and regulations are found in the Code of Federal Regulations. The Treasury regulations to which Russo may have been referring are found at title 26 ("Internal Revenue") of the Code of Federal Regulations,[17] not title 26 of the United States Code.[18] The argument that the Internal Revenue Code is not law, the argument that the Internal Revenue Code is not "positive law," and variations of these arguments, have been officially identified as legally frivolous Federal tax return positions for purposes of the $5,000 frivolous tax return penalty imposed under Internal Revenue Code section 6702(a).[19]

The article also discloses that Russo had over $2 million of tax liens filed against him by the Internal Revenue Service, the state of California, and the state of New York for unpaid taxes. In an interview with The New York Times; however, Russo refused to discuss the liens, saying they were not relevant to his film.[20]

Inaccuracies, distortions, and misrepresentations edit

Quotation of U.S. District Judge James C. Fox edit

Aaron Russo reads a quote attributed to U.S. District Judge James C. Fox:

If you ... examined [The 16th Amendment] carefully, you would find that a sufficient number of states never ratified that amendment.

The film does not mention the specific court case, which is Sullivan v. United States in the United States District Court for the Eastern District of North Carolina, case no. 03-CV-39 (2003).[21] In the case, the plaintiffs attempted unsuccessfully to prevent the deployment of troops to Iraq. The comments with respect to the Sixteenth Amendment did not constitute a ruling in the case (see Stare decisis) and were mentioned only in passing (see Obiter dictum). The transcript reads (in part):

I will say I think, you know, colonel, I have to tell you that there are cases where a long course of history in fact does change the Constitution, and I can think of one instance. I believe I'm correct on this. I think if you were to go back and try to find and review the ratification of the 16th amendment, which was the internal revenue, income tax, I think if you went back and examined that carefully, you would find that a sufficient number of states never ratified that amendment ... And nonetheless, I think it's fair to say that it is part of the Constitution of the United States, and I don't think any court would ever...set it aside.

Quotation of President Wilson edit

Aaron Russo reads a quote widely attributed[by whom?] to Woodrow Wilson:

I am a most unhappy man. I have unwittingly ruined my country. A great industrial nation is now controlled by its system of credit. We are no longer a government by free opinion, no longer a government by conviction and the vote of the majority, but a government by the opinion and duress of a small group of dominant men.

This is a well-known conflation of several quotes, only two of which can actually be attributed to Woodrow Wilson. The source of the first two sentences is unknown, and nowhere on record can be found to be said by Wilson.[citation needed] The third sentence (although slightly altered in this version) is found in the eighth chapter of Wilson's 1913 book, The New Freedom,[22] and originally reads:

A great industrial nation is controlled by its system of credit. Our system of credit is privately concentrated. The growth of the nation, therefore, and all our activities are in the hands of a few men who, even if their action be honest and intended for the public interest, are necessarily concentrated upon the great undertakings in which their own money is involved and who necessarily, by very reason of their own limitations, chill and check and destroy genuine economic freedom.

The final sentence (beginning with "We are no longer..."), although again slightly altered from its original version, can also be found in The New Freedom (ninth chapter), and in its original context, reads:

We have restricted credit, we have restricted opportunity, we have controlled development, and we have come to be one of the worst ruled, one of the most completely controlled and dominated, governments in the civilized world—no longer a government by free opinion, no longer a government by conviction and the vote of the majority, but a government by the opinion and the duress of small groups of dominant men.

That quotation, in this 1913-published book, was referring not at all to the Federal Reserve System, as this film alleges, but instead to the situation that preceded it and that Wilson was attacking: the "trusts" and "monopolies."

Quotation of Mussolini edit

Similarly, Russo uses a quotation that has for some time been attributed to Benito Mussolini:[23]

Fascism should more properly be called corporatism because it is the merger of state and corporate power.

Probably, the complete quote in Italian is:

"il corporativismo è la pietra angolare dello Stato fascista, anzi lo Stato fascista o è corporativo o non è fascista"[24]

Translation:

"corporatism is the corner stone of the Fascist nation, or better still, the Fascist nation is corporative or it is not fascist"

Quotation from President Bill Clinton edit

The film displays a quote:

"We can't be so fixated on our desire to preserve the rights of ordinary Americans." Bill Clinton, March 11, 1993

What Clinton actually said (on March 1, 1993[25]) was:

We can't be so fixated on our desire to preserve the rights of ordinary Americans to legitimately own handguns and rifles—it's something I strongly support—we can't be so fixated on that that we are unable to think about the reality of life that millions of Americans face on streets that are unsafe, under conditions that no other nation—no other nations—has permitted to exist.

Quotation from Judge Kent Dawson edit

Russo includes in text the following from a case against tax protester Irwin Schiff:[26]

Irwin Schiff: "But the Supreme Court said ..."

Judge Dawson: "Irrelevant! Denied!"

Irwin Schiff: "The Supreme Court is irrelevant???[sic]"

Judge Dawson: "Irrelevant! Denied!"

This is followed by Russo's verbal statement:

"Here we have a federal judge railroading an American citizen by saying Supreme Court decisions are irrelevant."

The first line of Schiff's statement in full is "But the Supreme Court said in the Cheek decision". In what follows, Dawson was stating that the Cheek v. United States decision was irrelevant to the particular argument that Schiff was trying to make at the time and not that Supreme Court decisions in general are irrelevant.[citation needed]

First Amendment edit

In the film, it is stated:

On August 31, 2005 federal judge Emmet Sullivan ruled the government does not have to answer the American people's questions, even though it is guaranteed in the First Amendment.

The text of the first amendment is as follows:

"Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances."

Claim that the film was shown at Cannes edit

Russo's promotional materials state that the film was shown at Cannes in France, implying that it was screened as part of the prestigious Cannes Film Festival. The film's web site states:

- America: Freedom to Fascism Opens to Standing Ovations at Cannes!

- The international audience at Cannes as well as the European media has been fascinated by Russo’s fiery diatribe against the direction America is heading.

According to a New York Times article by David Cay Johnston on July 31, 2006, however, the film was not "on the program" at the 2006 Cannes Film Festival itself; Russo actually rented an inflatable screen and showed the film on the beach at the town of Cannes during the time of the film festival. [dead link][20] The New York Times article states: "Photographs posted at one of Russo's Web sites depict an audience of fewer than 50 people spread out on a platform on the sand."[20]

Subsequently, it was exhibited in theaters in select U.S. cities.[27]

Reception edit

A review by The New York Times stated that "examination of the assertions in Russo’s documentary, which purports to expose 'two frauds' perpetrated by the federal government, taxing wages and creating the Federal Reserve to coin money, shows that they too collapse under the weight of fact."[20]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ Lee, Nathan (2006-07-28). "'America: Freedom to Fascism' Makes a Mess of the Mess We Are in". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved 2006-08-03.

- ^ Lisa Wangsness (2007-09-27). "Paul's their all". Boston Globe. at [1].

- ^ The sentence resulted from convictions on multiple counts of filing false tax returns for the years 1997 through 2002, aiding and assisting in the preparation of false tax returns filed by other taxpayers, conspiring to defraud the United States and income tax evasion. Schiff is currently serving his sentence.

- ^ In Schiff's objection to the prosecutor's presentence report, Schiff's lawyers stated that Schiff "suffers from severe mental problems" (see p. 2, Defendant Schiff's Objections to the Presentence Report, docket entry 373, Feb. 14, 2006, United States v. Schiff, case no. 2:04-cr-00119-KJD-LRL, U.S. District Court for the District of Nevada), and cited the results of a competency examination of Schiff conducted by Dr. Daniel Hayes to the effect that Schiff's conduct was "being driven by his mental illness." (p. 2, Id.).

- ^ For examples of application of this rule in tax cases, see United States v. Ambort, 405 F.3d 1109, 2005-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) paragr. 50,453 (10th Cir. 2005); United States v. Bonneau, 970 F.2d 929, 92-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) paragr. 50,385 (1st Cir. 1992); United States v. Willie, 91-2 U.S. Tax Cas. (CCH) paragr. 50,409 (10th Cir. 1991).

- ^ United States v. Kuglin, docket entry 39, case no. 2:03-cr-20111-JPM, United States District Court for the Western District of Tennessee, Memphis Div. (dated Aug. 8, 2003, entered Aug. 13, 2003).

- ^ David Cay Johnston, "Mistrial Is Declared in Tax Withholding Case," Nov. 27, 2003, The New York Times, at [2].

- ^ Kuglin v. Commissioner, United States Tax Court, docket no. 21743-03; 2004 TNT 177-6 (Sept. 13, 2004), as cited at [3]; and Daily Digest, Memphis Daily News, April 30, 2007, at [4].

- ^ Daily Digest, Memphis Daily News, April 30, 2007, at [5].

- ^ Regarding Federal income tax, see Article I, section 8, clause 1 of the United States Constitution, the Sixteenth Amendment, and various provisions of Title 26 of the United States Code defining gross income and taxable income, imposing the tax on the taxable income of individuals and imposing obligations to file the related tax returns, including 26 U.S.C. § 1, 26 U.S.C. § 61, 26 U.S.C. § 63, 26 U.S.C. § 6012, 26 U.S.C. § 6151, 26 U.S.C. § 6651, and 26 U.S.C. § 7203. At one point in the film (playback time 1:33:37) an individual named Edwin Vieira asserts that "The definition of income in the Constitution was given in the Eisner versus Macomber case. And it turns on gains or profits that are made from some activity. So the Supreme Court has rules. Income is not wages. It's not labor. It's gain from corporate activity." The Vieira quotation does not disclose the fact that neither the U.S. Supreme Court nor any other Federal court has ever ruled that wages are not income or that income means only gain from corporate activity. The terms "wage" and "salary" do not appear in the text of Eisner v. Macomber, 252 U.S. 189 (1920).

- ^ United States v. Schiff, 612 F.2d 73, 83 (2d Cir. 1979)

- ^ United States v. Sullivan, 274 U.S. 259, 263, 264 (1927)

- ^ United States v. Wong, 431 U.S. 174, 97 S.Ct. 1823, 52 L.Ed.2d 231, No. 74-635 (1977) "...the Fifth Amendment privilege does not condone perjury. It grants a privilege to remain silent without risking contempt, but it 'does not endow the person who testifies with a license to commit perjury.'"

- ^ United States v. Brown, 600 F.2d 248, 252 (10th Cir. 1979), cert. denied, 444 U.S. 917 (1979).

- ^ "America: Freedom to Fascism". Archived from the original on 2006-08-13. Retrieved 2006-07-31.

- ^ No Federal court at any level, either before or after the year 1913 ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, has upheld this argument. See tax protester arguments about taxation of labor or income from labor.

- ^ "Available CFR Titles on GPO Access". Archived from the original on 2007-07-01. Retrieved 2006-07-31.

- ^ The Internal Revenue Code is a set of statutes enacted by the U.S. Congress, not a set of administrative regulations. According to the United States Statutes at Large (published by the United States Government Printing Office) the Internal Revenue Code of 1954, the predecessor to the current 1986 code, was enacted by the Eighty-Third Congress of the United States with the phrase "Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled" and was "approved" (signed into law) at 9:45 A.M., Eastern Daylight Time, on August 16, 1954, and published as volume 68A of the United States Statutes at Large. Section 1(a)(1) of the enactment states: "The provisions of this Act set forth under the heading 'Internal Revenue Title' may be cited as the 'Internal Revenue Code of 1954'. Section 1(d) of the enactment is entitled "Enactment of Internal Revenue Title Into Law", and the text of the Code follows, beginning with the statutory Table of Contents. The enactment ends with the approval (enactment) notation on page 929. The '54 Code was also separately codified as title 26 of the United States Code and, according to CCH, Inc., a publisher of legal materials, all amendments to the 1954 Code (including the Tax Reform Act of 1986 which changed the name of the '54 Code to "Internal Revenue Code of 1986") have been made in the form of Acts of Congress. The table of contents for the United States Code at the website for the Legal Information Institute at Cornell University Law School lists title 26 of the United States Code as the "Internal Revenue Code"[6], as does the table of contents at the website for the U.S. Government Printing Office "United States Code: Browse". Archived from the original on 2005-09-30. Retrieved 2005-09-22.. See also positive law and the United States Code.

- ^ 26 U.S.C. § 6702, as amended by section 407 of the Tax Relief and Health Care Act of 2006, Pub. L. No. 109-432, 120 Stat. 2922 (Dec. 20, 2006). See Notice 2007-30, item (2), Internal Revenue Service, U.S. Dep’t of the Treasury (March 15, 2007). [Note: As of late September 2007, the linked page at the Cornell University Law School web site for section 6702 does not yet reflect the increase in the penalty amount from $500 to $5,000.]

- ^ a b c d Johnston, David Cay (2006-07-31). "Facts Refute Filmmaker's Assertions on Income Tax in 'America'". The New York Times. Retrieved 2006-08-03.

- ^ "Transcript of March 23, 2003 Hearing on Motion for Temporary Restraining Order in Sullivan v. United States" (PDF). Retrieved 2007-08-19.

- ^ Wilson, Woodrow. The New Freedom: A Call For the Emancipation of the Generous Energies of a People. Public domain.

- ^ "PublicEye.org – Fascism: Corporatism v. Corporations". Archived from the original on 2009-01-29. Retrieved 2007-02-14.

- ^ Somma, Alessandro (2005). I giuristi e l'Asse culturale Roma-Berlino: Economia e politica nel diritto fascista e nazionalsocialista. Klostermann. ISBN 9783465034469.

- ^ William J. Clinton: Remarks and a Question-and-Answer Session at the Adult Learning Center in New Brunswick, New Jersey

- ^ United States v. Schiff, 379 F.3d 621 (9th Cir. 2004)

- ^ Douglas, Edward (2006-07-28). "Also in Limited Release". Your Weekly Guide to New Movies for July 28, 2006. ComingSoon.net. Archived from the original on 10 August 2006. Retrieved 2006-08-03.

External links edit

- America: Freedom to Fascism

- America: Freedom to Fascism at IMDb

- America: Freedom to Fascism at AllMovie

- Income Tax: Voluntary or Mandatory? Archived 2007-10-24 at the Wayback Machine A law professor comments on the issues discussed in Russo's film

- Refutations of tax protester arguments from the Internal Revenue Service