| Set of uniform p-q duoprisms | |

| Type | Prismatic uniform 4-polytopes |

| Schläfli symbol | {p}×{q} |

| Coxeter-Dynkin diagram | |

| Cells | p q-gonal prisms, q p-gonal prisms |

| Faces | pq squares, p q-gons, q p-gons |

| Edges | 2pq |

| Vertices | pq |

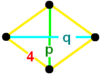

| Vertex figure |  disphenoid |

| Symmetry | [p,2,q], order 4pq |

| Dual | p-q duopyramid |

| Properties | convex, vertex-uniform |

| Set of uniform p-p duoprisms | |

| Type | Prismatic uniform 4-polytope |

| Schläfli symbol | {p}×{p} |

| Coxeter-Dynkin diagram | |

| Cells | 2p p-gonal prisms |

| Faces | p2 squares, 2p p-gons |

| Edges | 2p2 |

| Vertices | p2 |

| Symmetry | [p,2,p] = [2p,2+,2p], order 8p2 |

| Dual | p-p duopyramid |

| Properties | convex, vertex-uniform, Facet-transitive |

In geometry of 4 dimensions or higher, a double prism[1] or duoprism is a polytope resulting from the Cartesian product of two polytopes, each of two dimensions or higher. The Cartesian product of an n-polytope and an m-polytope is an (n+m)-polytope, where n and m are dimensions of 2 (polygon) or higher.

The lowest-dimensional duoprisms exist in 4-dimensional space as 4-polytopes being the Cartesian product of two polygons in 2-dimensional Euclidean space. More precisely, it is the set of points:

where P1 and P2 are the sets of the points contained in the respective polygons. Such a duoprism is convex if both bases are convex, and is bounded by prismatic cells.

Nomenclature edit

Four-dimensional duoprisms are considered to be prismatic 4-polytopes. A duoprism constructed from two regular polygons of the same edge length is a uniform duoprism.

A duoprism made of n-polygons and m-polygons is named by prefixing 'duoprism' with the names of the base polygons, for example: a triangular-pentagonal duoprism is the Cartesian product of a triangle and a pentagon.

An alternative, more concise way of specifying a particular duoprism is by prefixing with numbers denoting the base polygons, for example: 3,5-duoprism for the triangular-pentagonal duoprism.

Other alternative names:

- q-gonal-p-gonal prism

- q-gonal-p-gonal double prism

- q-gonal-p-gonal hyperprism

The term duoprism is coined by George Olshevsky, shortened from double prism. John Horton Conway proposed a similar name proprism for product prism, a Cartesian product of two or more polytopes of dimension at least two. The duoprisms are proprisms formed from exactly two polytopes.

Example 16-16 duoprism edit

| Schlegel diagram Projection from the center of one 16-gonal prism, and all but one of the opposite 16-gonal prisms are shown. |

net The two sets of 16-gonal prisms are shown. The top and bottom faces of the vertical cylinder are connected when folded together in 4D. |

Geometry of 4-dimensional duoprisms edit

A 4-dimensional uniform duoprism is created by the product of a regular n-sided polygon and a regular m-sided polygon with the same edge length. It is bounded by n m-gonal prisms and m n-gonal prisms. For example, the Cartesian product of a triangle and a hexagon is a duoprism bounded by 6 triangular prisms and 3 hexagonal prisms.

- When m and n are identical, the resulting duoprism is bounded by 2n identical n-gonal prisms. For example, the Cartesian product of two triangles is a duoprism bounded by 6 triangular prisms.

- When m and n are identically 4, the resulting duoprism is bounded by 8 square prisms (cubes), and is identical to the tesseract.

The m-gonal prisms are attached to each other via their m-gonal faces, and form a closed loop. Similarly, the n-gonal prisms are attached to each other via their n-gonal faces, and form a second loop perpendicular to the first. These two loops are attached to each other via their square faces, and are mutually perpendicular.

As m and n approach infinity, the corresponding duoprisms approach the duocylinder. As such, duoprisms are useful as non-quadric approximations of the duocylinder.

Nets edit

| 3-3 | |||||||

| 3-4 |

4-4 | ||||||

| 3-5 |

4-5 |

5-5 | |||||

| 3-6 |

4-6 |

5-6 |

6-6 | ||||

| 3-7 |

4-7 |

5-7 |

6-7 |

7-7 | |||

| 3-8 |

4-8 |

5-8 |

6-8 |

7-8 |

8-8 | ||

| 3-9 |

4-9 |

5-9 |

6-9 |

7-9 |

8-9 |

9-9 | |

| 3-10 |

4-10 |

5-10 |

6-10 |

7-10 |

8-10 |

9-10 |

10-10 |

Perspective projections edit

A cell-centered perspective projection makes a duoprism look like a torus, with two sets of orthogonal cells, p-gonal and q-gonal prisms.

| 6-prism | 6-6 duoprism |

|---|---|

| A hexagonal prism, projected into the plane by perspective, centered on a hexagonal face, looks like a double hexagon connected by (distorted) squares. Similarly a 6-6 duoprism projected into 3D approximates a torus, hexagonal both in plan and in section. | |

The p-q duoprisms are identical to the q-p duoprisms, but look different in these projections because they are projected in the center of different cells.

| 3-3 |

3-4 |

3-5 |

3-6 |

3-7 |

3-8 |

| 4-3 |

4-4 |

4-5 |

4-6 |

4-7 |

4-8 |

| 5-3 |

5-4 |

5-5 |

5-6 |

5-7 |

5-8 |

| 6-3 |

6-4 |

6-5 |

6-6 |

6-7 |

6-8 |

| 7-3 |

7-4 |

7-5 |

7-6 |

7-7 |

7-8 |

| 8-3 |

8-4 |

8-5 |

8-6 |

8-7 |

8-8 |

Orthogonal projections edit

Vertex-centered orthogonal projections of p-p duoprisms project into [2n] symmetry for odd degrees, and [n] for even degrees. There are n vertices projected into the center. For 4,4, it represents the A3 Coxeter plane of the tesseract. The 5,5 projection is identical to the 3D rhombic triacontahedron.

| Odd | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3-3 | 5-5 | 7-7 | 9-9 | ||||||||

| [3] | [6] | [5] | [10] | [7] | [14] | [9] | [18] | ||||

| Even | |||||||||||

| 4-4 (tesseract) | 6-6 | 8-8 | 10-10 | ||||||||

| [4] | [8] | [6] | [12] | [8] | [16] | [10] | [20] | ||||

Related polytopes edit

The regular skew polyhedron, {4,4|n}, exists in 4-space as the n2 square faces of a n-n duoprism, using all 2n2 edges and n2 vertices. The 2n n-gonal faces can be seen as removed. (skew polyhedra can be seen in the same way by a n-m duoprism, but these are not regular.)

Duoantiprism edit

Like the antiprisms as alternated prisms, there is a set of 4-dimensional duoantiprisms: 4-polytopes that can be created by an alternation operation applied to a duoprism. The alternated vertices create nonregular tetrahedral cells, except for the special case, the 4-4 duoprism (tesseract) which creates the uniform (and regular) 16-cell. The 16-cell is the only convex uniform duoantiprism.

The duoprisms , t0,1,2,3{p,2,q}, can be alternated into , ht0,1,2,3{p,2,q}, the "duoantiprisms", which cannot be made uniform in general. The only convex uniform solution is the trivial case of p=q=2, which is a lower symmetry construction of the tesseract , t0,1,2,3{2,2,2}, with its alternation as the 16-cell, , s{2}s{2}.

The only nonconvex uniform solution is p=5, q=5/3, ht0,1,2,3{5,2,5/3}, , constructed from 10 pentagonal antiprisms, 10 pentagrammic crossed-antiprisms, and 50 tetrahedra, known as the great duoantiprism (gudap).[2][3]

Ditetragoltriates edit

Also related are the ditetragoltriates or octagoltriates, formed by taking the octagon (considered to be a ditetragon or a truncated square) to a p-gon. The octagon of a p-gon can be clearly defined if one assumes that the octagon is the convex hull of two perpendicular rectangles; then the p-gonal ditetragoltriate is the convex hull of two p-p duoprisms (where the p-gons are similar but not congruent, having different sizes) in perpendicular orientations. The resulting polychoron is isogonal and has 2p p-gonal prisms and p2 rectangular trapezoprisms (a cube with D2d symmetry) but cannot be made uniform. The vertex figure is a triangular bipyramid.

Double antiprismoids edit

Like the duoantiprisms as alternated duoprisms, there is a set of p-gonal double antiprismoids created by alternating the 2p-gonal ditetragoltriates, creating p-gonal antiprisms and tetrahedra while reinterpreting the non-corealmic triangular bipyramidal spaces as two tetrahedra. The resulting figure is generally not uniform except for two cases: the grand antiprism and its conjugate, the pentagrammic double antiprismoid (with p = 5 and 5/3 respectively), represented as the alternation of a decagonal or decagrammic ditetragoltriate. The vertex figure is a variant of the sphenocorona.

k_22 polytopes edit

The 3-3 duoprism, -122, is first in a dimensional series of uniform polytopes, expressed by Coxeter as k22 series. The 3-3 duoprism is the vertex figure for the second, the birectified 5-simplex. The fourth figure is a Euclidean honeycomb, 222, and the final is a paracompact hyperbolic honeycomb, 322, with Coxeter group [32,2,3], . Each progressive uniform polytope is constructed from the previous as its vertex figure.

| Space | Finite | Euclidean | Hyperbolic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| Coxeter group |

A2A2 | E6 | =E6+ | =E6++ | |

| Coxeter diagram |

|||||

| Symmetry | [[32,2,-1]] | [[32,2,0]] | [[32,2,1]] | [[32,2,2]] | [[32,2,3]] |

| Order | 72 | 1440 | 103,680 | ∞ | |

| Graph | ∞ | ∞ | |||

| Name | −122 | 022 | 122 | 222 | 322 |

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ The Fourth Dimension Simply Explained, Henry P. Manning, Munn & Company, 1910, New York. Available from the University of Virginia library. Also accessible online: The Fourth Dimension Simply Explained—contains a description of duoprisms (double prisms) and duocylinders (double cylinders). Googlebook

- ^ Jonathan Bowers - Miscellaneous Uniform Polychora 965. Gudap

- ^ http://www.polychora.com/12GudapsMovie.gif Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine Animation of cross sections

References edit

- Regular Polytopes, H. S. M. Coxeter, Dover Publications, Inc., 1973, New York, p. 124.

- Coxeter, The Beauty of Geometry: Twelve Essays, Dover Publications, 1999, ISBN 0-486-40919-8 (Chapter 5: Regular Skew Polyhedra in three and four dimensions and their topological analogues)

- Coxeter, H. S. M. Regular Skew Polyhedra in Three and Four Dimensions. Proc. London Math. Soc. 43, 33-62, 1937.

- John H. Conway, Heidi Burgiel, Chaim Goodman-Strauss, The Symmetries of Things 2008, ISBN 978-1-56881-220-5 (Chapter 26)

- N.W. Johnson: The Theory of Uniform Polytopes and Honeycombs, Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Toronto, 1966