IntroductionA star is a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by self-gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night; their immense distances from Earth make them appear as fixed points of light. The most prominent stars have been categorised into constellations and asterisms, and many of the brightest stars have proper names. Astronomers have assembled star catalogues that identify the known stars and provide standardized stellar designations. The observable universe contains an estimated 1022 to 1024 stars. Only about 4,000 of these stars are visible to the naked eye—all within the Milky Way galaxy. A star's life begins with the gravitational collapse of a gaseous nebula of material largely comprising hydrogen, helium, and trace heavier elements. Its total mass mainly determines its evolution and eventual fate. A star shines for most of its active life due to the thermonuclear fusion of hydrogen into helium in its core. This process releases energy that traverses the star's interior and radiates into outer space. At the end of a star's lifetime as a fusor, its core becomes a stellar remnant: a white dwarf, a neutron star, or—if it is sufficiently massive—a black hole. Stellar nucleosynthesis in stars or their remnants creates almost all naturally occurring chemical elements heavier than lithium. Stellar mass loss or supernova explosions return chemically enriched material to the interstellar medium. These elements are then recycled into new stars. Astronomers can determine stellar properties—including mass, age, metallicity (chemical composition), variability, distance, and motion through space—by carrying out observations of a star's apparent brightness, spectrum, and changes in its position in the sky over time. Stars can form orbital systems with other astronomical objects, as in planetary systems and star systems with two or more stars. When two such stars orbit closely, their gravitational interaction can significantly impact their evolution. Stars can form part of a much larger gravitationally bound structure, such as a star cluster or a galaxy. (Full article...) Selected star - Photo credit: Digitized Sky Survey, NASA

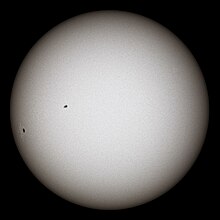

Arcturus (/ɑːrkˈtjʊərəs/; α Boo, α Boötis, Alpha Boötis) of the constellation Boötes is the brightest star in the northern celestial hemisphere. With a visual magnitude of −0.04, it is the fourth brightest star in the night sky, after −1.46 magnitude Sirius, −0.86 magnitude Canopus, and −0.27 magnitude Alpha Centauri. It is a relatively close star at only 36.7 light-years from Earth, and, together with Vega and Sirius, one of the most luminous stars in the Sun's neighborhood. Arcturus is a type K0 III orange giant star, with an absolute magnitude of −0.30. It has likely exhausted its hydrogen from its core and is currently in its active hydrogen shell burning phase. It will continue to expand before entering horizontal branch stage of its life cycle. Arcturus is a type K0 III Red giant star. It is at least 110 times more luminous than the Sun in visible light wavelengths, but this underestimates its strength as much of the "light" it gives off is in the infrared; total (bolometric) power output is about 180 times that of the Sun. The lower output in visible light is due to a lower efficacy as the star has a lower surface temperature than the Sun. As the brightest K-type giant in the sky, it was the subject of an atlas of its visible spectrum, made from photographic spectra taken with the coudé spectrograph of the Mt. Wilson 2.5m telescope published in 1968, a key reference work for stellar spectroscopy. Selected article - Photo credit: User:Alain r

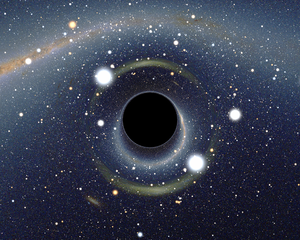

According to the general theory of relativity, a black hole is a region of space from which nothing, including light, can escape. It is the result of the deformation of spacetime caused by a very compact mass. Around a black hole there is an undetectable surface which marks the point of no return, called an event horizon. It is called "black" because it absorbs all the light that hits it, reflecting nothing, just like a perfect black body in thermodynamics. Under the theory of quantum mechanics black holes possess a temperature and emit Hawking radiation. Despite its invisible interior, a black hole can be observed through its interaction with other matter. A black hole can be inferred by tracking the movement of a group of stars that orbit a region in space. Alternatively, when gas falls into a stellar black hole from a companion star, the gas spirals inward, heating to very high temperatures and emitting large amounts of radiation that can be detected from earthbound and Earth-orbiting telescopes. Astronomers have identified numerous stellar black hole candidates, and have also found evidence of supermassive black holes at the center of galaxies. After observing the motion of nearby stars for 16 years, in 2008 astronomers found compelling evidence that a supermassive black hole of more than 4 million solar masses is located near the Sagittarius A* region in the center of the Milky Way galaxy. Selected image - Photo credit: Hubble Space Telescope/NASA and ESA

A planetary nebula is an emission nebula consisting of an expanding glowing shell of ionized gas and plasma ejected during the asymptotic giant branch phase of certain types of stars late in their life. This name originated with their first discovery in the 18th century because of their similarity in appearance to giant planets when viewed through small optical telescopes, and is otherwise unrelated to the planets of the solar system. They are a relatively short-lived phenomenon, lasting a few tens of thousands of years, compared to a typical stellar lifetime of several billion years. Planetary nebulae play a crucial role in the chemical evolution of the galaxy, returning material to the interstellar medium that has been enriched in heavy elements and other products of nucleosynthesis. Did you know?

SubcategoriesTo display all subcategories click on the ►

Selected biography - Photo credit: State Post Bureau of the People's Republic of China

Zhang Heng (simplified Chinese: 张衡; traditional Chinese: 張衡; pinyin: Zhāng Héng; Wade–Giles: Chang Heng) (CE 78–139) was a Chinese astronomer, mathematician, inventor, geographer, cartographer, artist, poet, statesman and literary scholar from Nanyang, Henan. He lived during the Eastern Han Dynasty (CE 25–220) of China. He was educated in the capital cities of Luoyang and Chang'an, and began his career as a minor civil servant in Nanyang. Eventually, he became Chief Astronomer, Prefect of the Majors for Official Carriages, and then Palace Attendant at the imperial court. His uncompromising stances on certain historical and calendrical issues led to Zhang being considered a controversial figure, which prevented him from becoming an official court historian. His political rivalry with the palace eunuchs during the reign of Emperor Shun (r. 125–144) led to his decision to retire from the central court to serve as an administrator of Hejian, in Hebei. He returned home to Nanyang for a short time, before being recalled to serve in the capital once more in 138. He died there a year later, in 139. Zhang applied his extensive knowledge of mechanics and gears in several of his inventions. He invented the world's first water-powered armillary sphere, to represent astronomical observation; improved the inflow water clock by adding another tank; and invented the world's first seismometer, which discerned the cardinal direction of an earthquake 500 km (310 mi) away. Furthermore, he improved previous Chinese calculations of the formula for pi. In addition to documenting about 2,500 stars in his extensive star catalogue, Zhang also posited theories about the Moon and its relationship to the Sun; specifically, he discussed the Moon's sphericity, its illumination by reflecting sunlight on one side and remaining dark on the other, and the nature of solar and lunar eclipses. His fu (rhapsody) and shi poetry were renowned and commented on by later Chinese writers. Zhang received many posthumous honors for his scholarship and ingenuity, and is considered a polymath by some scholars. Some modern scholars have also compared his work in astronomy to that of Ptolemy (CE 86–161).

TopicsThings to do

Related portalsAssociated WikimediaThe following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

Discover Wikipedia using portals |