Walter Carl Becker (February 20, 1950 – September 3, 2017) was an American musician, songwriter, and record producer. He was the co-founder, guitarist, bassist, and co-songwriter of the jazz rock band Steely Dan.[1][2]

Walter Becker | |

|---|---|

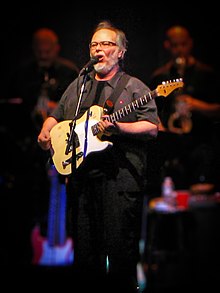

Becker performing in 2013 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Walter Carl Becker |

| Born | February 20, 1950 Queens, New York, U.S. |

| Died | September 3, 2017 (aged 67) Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz rock |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instrument(s) |

|

| Years active | 1969–2017 |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | |

| Website | walterbecker |

Becker met future songwriting partner Donald Fagen while they were students at Bard College. After a brief period of activity in New York City, the two moved to Los Angeles in 1971 and formed the nucleus of Steely Dan, which enjoyed a critically and commercially successful ten-year career. Following the group's dissolution, Becker moved to Hawaii and reduced his musical activity, working primarily as a record producer. In 1985, he briefly became a member of the English band China Crisis, producing and playing synthesizer on their album Flaunt the Imperfection.

Becker and Fagen reformed Steely Dan in 1993 and remained active, recording Two Against Nature (2000), which won four Grammy Awards. Becker released two solo albums, 11 Tracks of Whack (1994) and Circus Money (2008). Following a brief battle with esophageal cancer, he died on September 3, 2017. He and Fagen are the only two members of Steely Dan who appeared on every studio album by the band.

Early life and career (1950–1971) edit

Becker was born in Queens, New York City. After Becker's parents separated when he was a boy, his British mother returned to England. Becker was made to believe by his father and grandmother that his mother was deceased, but at some point between his childhood and late adolescence, he discovered that she was living, and he maintained a rocky relationship with her from then on.[3] He was raised in Queens and Scarsdale, New York[4] by his father and his grandmother. His father, Carl Becker, sold paper-cutting machinery in Manhattan[5] where Walter graduated from Stuyvesant High School.[6] After starting out on saxophone, he switched to guitar and received instruction in blues technique from neighbor Randy California, who later formed the band Spirit.[7]

Donald Fagen overheard Becker playing guitar at a campus coffee shop, the Red Balloon, when they were both students at Bard College in Annandale-on-Hudson, New York. In a 2007 interview Fagen said, "I hear this guy practicing, and it sounded very professional and contemporary. It sounded like, you know, like a black person, really."[8][9] They formed the band Leather Canary, which included fellow student Chevy Chase on drums.[10] At the time, Chase called the group "a bad jazz band."[11]

Becker left the school in 1969 before completing his degree and moved with Fagen to Brooklyn, where the two began to build a career as a songwriting duo. They were members of the touring band for Jay and the Americans[12] but used the pseudonyms Gus Mahler (Becker) and Tristan Fabriani (Fagen).[13] They composed music for the soundtrack to You've Got to Walk It Like You Talk It or You'll Lose That Beat, a 1971 film starring Richard Pryor.[14][15]

With Steely Dan (1971–1981) edit

In 1971, Becker and Fagen moved to Los Angeles and were hired by Gary Katz as staff songwriters at ABC Records, later forming Steely Dan with guitarists Denny Dias and Jeff "Skunk" Baxter, drummer Jim Hodder, and vocalist David Palmer. Fagen played keyboards and sang, while Becker played bass guitar.[16][17][18] Steely Dan spent the next three years touring and recording before swearing off touring in 1974, confining themselves to the studio with personnel that changed for every album. In addition to co-writing all of the band's material, Becker played guitar and bass guitar and sang background vocals.[12]

Pretzel Logic (1974) was the first Steely Dan album to feature Becker on guitar. "Once I met [session musician] Chuck Rainey", he explained, "I felt there really was no need for me to be bringing my bass guitar to the studio anymore".[19]

Despite the success of Aja in 1977, Becker suffered from setbacks during this period, including an addiction to narcotics. After the duo returned to New York in 1978, Becker's girlfriend Karen Roberta Stanley, who was an employee of ABC Dunhill Records and personal manager for the band, died of a drug overdose in his apartment on January 30, 1980, resulting in a wrongful death lawsuit against him. Soon after, he was hit by a cab in Manhattan while crossing the street and was forced to walk with crutches while recovering.[6] His exhaustion was made worse by commercial pressure and the complicated recording of the album Gaucho (1980). Becker and Fagen suspended their partnership in June 1981.[20]

Work in record production (1981–1993) edit

Following Steely Dan's breakup, Becker and his family moved to Maui. Becker ceased using drugs,[21][22][23] stopped smoking and drinking,[24] and became an "avocado rancher and self-styled critic of the contemporary scene."[25]

He produced albums for the new wave bands Fra Lippo Lippi and China Crisis, and is credited on the latter's 1985 album Flaunt the Imperfection as a member of the band.[16] He also produced albums for Michael Franks and John Beasley.[26] Becker produced Rickie Lee Jones's album Flying Cowboys (certified gold by the RIAA in 1997[27]) and played bass on the title track.[28] Becker and Fagen reunited in 1986 to collaborate on Zazu, the debut album by Rosie Vela.[29] In 1991, Becker appeared in Fagen's New York Rock and Soul Revue.[30]

Steely Dan reformation (1993–2017) edit

In 1993, Becker produced Fagen's album Kamakiriad.[31] A year later, Fagen co-produced Becker's debut album 11 Tracks of Whack.[32]

Also in 1993, Steely Dan began touring for the first time in nineteen years, resulting in the 1995 release of their first live album, Alive in America, a compilation of live recordings from different American tour dates in 1993 and 1994.

In 2000 they released Two Against Nature, their first album of new material in twenty years. The album won four Grammy Awards, including Album of the Year. In 2001 they were inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and received honorary doctorates from the Berklee College of Music, which they accepted in person.[33] In 2003, they released the album Everything Must Go with Becker singing lead vocal on "Slang of Ages".[34] They followed the album with a tour.[35]

In 2005, Becker co-produced and played bass guitar on the album All One by Krishna Das and played guitar on the album Tough on Crime by Rebecca Pidgeon. He co-wrote "I'm All Right" from the album Half the Perfect World (2006) by Madeleine Peyroux, and "You Can't Do Me" and the title track from her album Bare Bones (2009). See the "Collaborations" section below for a full list of Becker's work with other artists.

He was inducted into the Long Island Music Hall of Fame in 2008.[36]

His second solo album, Circus Money, was released on June 10, 2008, fourteen years after its predecessor.[37] The songs were inspired by reggae and other styles of Jamaican music.[7]

Instruments and equipment edit

Becker was a collector of musical equipment, accumulating hundreds of guitars and amplifiers, as well as numerous other instruments, pedals, pre-wired pedalboards, "speakers, recording gear, and ephemera."[38] In concert, he often played custom-built guitars modeled after Stratocasters.[39]

After his death, his gear was auctioned off by Julien's for US$3.3 million in total. Becker's guitar and amp collection was the largest ever sold by Julien's, whose owner said "what made [the] collection unique" was that Becker "literally played all of them."[38][40][41][42]

In a column for Guitar Player magazine published in 1994, Becker coined the acronym G.A.S. ("Guitar Acquisition Syndrome"), denoting the uncontrolled accumulation of music gear.[43][44] The term was later adapted as Gear Acquisition Syndrome in online forums and music magazines.

Personal life edit

In 1975 Becker married Juanna Fatouros.[45][46] In 1984 he married Elinor Roberta Meadows, a yoga teacher, and the couple had a son [47] and an adopted daughter Sayan.[48] They divorced in 1997. Becker wrote "Little Kawai" for his son, and it became the final song on 11 Tracks of Whack.[49][5]

Becker is survived by his wife Delia (née Cioffi).[50]

Illness and death edit

In the spring of 2017, Becker was diagnosed with "an aggressive form of esophageal cancer" during an annual medical checkup.[51] Despite undergoing vigorous treatment, the cancer rapidly worsened to the point that he did not perform at Steely Dan's concerts in the months that followed. He died from the disease on September 3, 2017, at the age of 67[52] at his home in Manhattan, New York City.[53] At the time of his death, no cause or other details were announced,[16] but a statement released in November by Becker's widow, Delia Becker, detailed his struggle with the disease.[54]

In a statement released to the media the day of Becker's death, Fagen recalled his long-time friend and musical partner as "smart as a whip, an excellent guitarist and a great songwriter," and closed by stating that he intended to "keep the music we created together alive as long as I can with the Steely Dan band."[55]

Julian Lennon,[56] Steve Lukather,[57] John Darnielle of The Mountain Goats[58] and other musicians made public statements mourning Becker's death. Rickie Lee Jones, whose album Flying Cowboys was produced by Becker, recalled her long friendship with him in an editorial she wrote for Rolling Stone.[59]

At a public ceremony on 28 October 2018, 72nd Drive at 112th Street, Forest Hills, Queens, New York City, was co-named Walter Becker Way.[60][61]

Discography edit

Studio albums edit

- 1994: 11 Tracks of Whack (Giant Records)

- 2008: Circus Money (5 over 12/Mailboat Records; Sonic 360 (UK); Victor (Japan))[62]

Collaborations edit

The sources for this section include walterbecker.com,[63] AllMusic[64] and Discogs.[65]

- 1969: Terence Boylan, Alias Boona (Verve Forecast) – guitar, bass

- 1970: Linda Hoover, I Mean To Shine (Omnivore Recordings, released 2022) – bass, arranger, co-writer (with Donald Fagen) of five songs

- 1970–1971: Jay and the Americans, touring band – bass

- 1970: Jay and the Americans, Capture the Moment (United Artists), "Capture the Moment", "Tricia (Tell Your Daddy)", "She’ll Be Young Forever" and "Thoughts That I’ve Taken To Bed" – co-arranger (with Donald Fagen) strings and horns, bass

- 1971: The Original Soundtrack, You've Got to Walk It Like You Talk It or You'll Lose That Beat (Spark Records), film soundtrack – co-writer and co-arranger (with Donald Fagen), bass

- 1972: Navasota, Rootin' (ABC Records) – co-arranger strings and horns (with Donald Fagen); "Canyon Ladies" – co-writer (with Donald Fagen)

- 1973: Thomas Jefferson Kaye,Thomas Jefferson Kaye (Dunhill Records), "I’ll Be Leaving Her Tomorrow" and "Hole In The Shoe Blues" – bass

- 1974: Thomas Jefferson Kaye, First Grade (ABC/Dunhill Records), "Jones" and "American Lovers" – bass

- 1978: Pete Christlieb and Warne Marsh, Apogee (Warner Bros.) – co-producer (with Donald Fagen)

- 1985: China Crisis, Flaunt the Imperfection (Virgin) – producer, arranger, synthesiser, percussion

- 1986: Rosie Vela, Zazu (A&M) – lead guitar, guitar, synthesiser

- 1987: Fra Lippo Lippi, Light and Shade (Virgin) – producer, guitar

- 1989: China Crisis, Diary of a Hollow Horse (Virgin) – producer, synthesiser

- 1989: Michael Franks, Blue Pacific (Reprise), "All I need", "Vincent's Ear" and "Crayon Sun (Safe At Home)" – producer

- 1989: Rickie Lee Jones, Flying Cowboys (Geffen) – producer, bass on "Flying Cowboys"

- 1991: Nathalie Archangel, Owl (MCA Records) – bass

- 1991: LeeAnn Ledgerwood, You Wish (Triloka Records) – producer

- 1991: Jeff Beal, Objects In The Mirror (Triloka Records) – producer

- 1991: Bob Sheppard, Tell Tale Signs (Windham Hill Jazz) – producer

- 1991: Andy LaVerne, Pleasure Seekers (Triloka Records) – producer

- 1991: Bob Bangerter, Looking At The Bright Side (Don't Stop Music, Inc.) – mixing, co-producer (with Tom Hall)

- 1991: The New York Rock and Soul Revue, live dates – guitar

- 1992: Spinal Tap, Break Like the Wind (MCA Records) – liner notes

- 1992: Jeremy Steig, Jigsaw (Triloka Records) – producer

- 1992: John Beasley, Cauldron (Windham Hill Jazz) – producer

- 1992: Dave Kikoski, Persistent Dreams (Triloka Records) – producer, liner notes

- 1992: Marty Krystall, unreleased album, "Epistrophy" (on Windham Hill sampler Commotion 2) – producer

- 1993 The Singing Mongooses, The Singing Mongooses (Alahao Records) – executive producer

- 1993: Lost Tribe, Lost Tribe (Windham Hill Jazz) – producer

- 1993: Andy LaVerne, Double Standard (Triloka Records) – producer

- 1993: John Beasley, A Change Of Heart (Windham Hill Jazz) – producer

- 1993: Donald Fagen, Kamakiriad (Reprise) – producer, bass, guitar

- 1994: John Beasley, Mose the Fireman (Rabbit Ears Productions) – producer (music), co-writer (with John Beasley), bass, banjo, mandolin

- 1998: Sally Taylor, Tomboy Bride (Blue Elbow Publishing) – mixing

- 2005: Krishna Das, All One (Triloka Records) – producer, bass

- 2005: Marian McPartland, Marian McPartland's Piano Jazz With Steely Dan (Jazz Alliance, recorded 2002) – guitar, conversation

- 2005: Rebecca Pidgeon, Tough on Crime (Fuel 2000), "Tough on Crime" – guitar solo

- 2006: Madeleine Peyroux, Half the Perfect World (Rounder/Universal), "I'm All Right" – co-writer (with Larry Klein and Madeleine Peyroux)

- 2008: Lucy Schwartz, "Beautiful" (single) – co-producer (with Larry Klein)

- 2009: Madeleine Peyroux, Bare Bones (Rounder/Universal), "Bare Bones" and "You Can't Do Me" – co-writer (with Larry Klein and Madeleine Peyroux)

- 2009: Roger Rosenberg, Baritonality (Sunnyside Communications) – producer

References edit

- ^ "STEELY DAN biography". Great Rock Bible. Archived from the original on October 23, 2013. Retrieved August 3, 2013.

- ^ Russonello, Giovanni, "Listen to 13 Essential Walter Becker Songs." New York Times, 2017-09-04. Accessed 2019-05-29.

- ^ J. L. Kelley (2021). "West of Hollywood: Humor as reparation in the life and work of Walter Becker." In: E. Vanderheiden & C.-H. Mayer (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Humour Research (pp. 363-379). London: Palgrave Macmillan

- ^ Wllkinson, Alec (March 30, 2000). "Steely Dan: Return of the Dark Brothers". rollingstone.com. Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 21, 2019.

- ^ a b Wilkinson, Alec (March 30, 2000). "Steely Dan: Return of the Dark Brothers". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ a b Sweet, Brian (2000). Steely Dan: Reelin' in the Years. Omnibus Press. pp. 11–. ISBN 978-0-7119-8279-6. Retrieved June 18, 2009.

Walter Becker was born on Monday, February 20, 1950, in the Forest Hills area of Queens in New York

- ^ a b Bonzai, Mr. (September 1, 2008). "Solo 'Circus Money' Has Deep Grooves". Mix Online. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ Brunner, Rob (March 17, 2006). "Back to Annandale: The Origins of Steely Dan". EW.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2007. Retrieved March 22, 2012.

- ^ Brunner, Rob (March 17, 2006). "Back to Annandale (article originally from Entertainment Weekly)". The Steely Dan Reader. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Morris, Chris (September 3, 2017). "Walter Becker, Steely Dan Guitarist, Dies at 67". Variety. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel (2012). Rock 'n' Roll Myths: The True Stories Behind the Most Infamous Legends. Minneapolis, MN: Voyageur Press. p. 204. ISBN 978-0760342305.

- ^ a b Kreps, Daniel (September 3, 2017). "Walter Becker, Steely Dan Co-Founder, Dead at 67". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Perry, Charles (August 15, 1974). "Steely Dan Comes Up Swinging: Number Five With a Dildo". Rolling Stone. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ Weiler, A. H. (September 20, 1971). "'You've Got to Walk It...,' Genial Put-Down of Establishment". The New York Times. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "You've Got to Walk It Like You Talk It or You'll Lose That Beat". IMDB. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c Pareles, Jon (September 3, 2017). "Walter Becker, Guitarist, Songwriter and Co-Founder of Steely Dan, Dies at 67". The New York Times. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ "The Return of Steely Dan". Mojo Magazine. October 1995. Retrieved December 15, 2006.

- ^ "Official Steely Dan FAQ". Archived from the original on December 27, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2007.

- ^ Gill, Andy (April 1995). "Hasn't He Grown". Q. No. 103. EMAP Metro. pp. 41–43.

- ^ Anderson, Stacy (June 21, 2011). "When Jimmy Page Debuted With the Yardbirds and Steely Dan Broke Up". Rolling Stone. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ Kamiya, Gary (March 14, 2000). "Sophisticated Skank". Salon. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Cromelin, Richard (November 3, 1991). "Return of the Nightfly". The Steely Dan Reader. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Powell, Mike (June 27, 2006). "Steely Dan – Gaucho". Stylus Magazine. Archived from the original on August 7, 2020. Retrieved June 19, 2008.

- ^ Woodard, Josef (November 2017). "Remembering Walter Becker: A Maverick in Plain Sight". Downbeat. Elmhurst, Illinois. p. 24.

- ^ "Timeline Bio". Steely Dan. Archived from the original on March 16, 2012. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ "RIP Walter Becker of Steely Dan". Rhino Records. Retrieved September 4, 2017.

- ^ "Gold & Platinum". RIAA. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "Flying Cowboys". AllMusic. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ Henderson, Alex. "Zazu – Rosie Vela". AllMusic. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Willman, Chris (September 3, 2017). "The 1993 interview when Walter Becker opened up about Steely Dan's subversive intentions". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Browne, David (May 28, 1993). "Kamakiriad". EW.com. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ Ruhlmann, William. "11 Tracks of Whack". AllMusic. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ "Commencement 2001 – Berklee College of Music". Berklee.edu. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Frazier, Preston (October 13, 2013). "Steely Dan Sunday, "Slang of Ages" (2003)". Something Else!. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ Sweet, Brian (February 9, 2015). Steely Dan: Reelin' in the Years. Omnibus Press. ISBN 9781783235292. Retrieved September 3, 2017 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Long Island Music Hall of Fame – Preserving & Celebrating the Long Island musical heritage". Limusichalloffame.org. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "walter becker – circus money – official site". Walter Becker. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ a b "Event Details". www.juliensauctions.com. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ "Can Buy a Thrill: The luthier-built guitars of Walter Becker". Fretboard Journal. September 17, 2020. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ Chelin, Pamela (October 21, 2019). "Steely Dan's Walter Becker Estate Auction Fetches $3.3M on Hundreds of Guitars, Amps & More". Billboard. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ "Steely Dan's Walter Becker was a gearhead's gearhead. Now his entire collection is up for auction". Los Angeles Times. October 17, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2022.

- ^ "Auction results: property from the estate of Walter Becker". Julien's Auctions. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ Walter Becker: "The Dreaded G.A.S.", in: Guitar Player, April 1994, p. 15.

- ^ Becker, Walter (1996). "G.A.S." The Steely Dan Internet Archive. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ Sweet, Brian (2015). Steely Dan: Reelin' in the Years (2nd ed.). Omnibus Press. pp. 320–321. ISBN 978-1783056231.

- ^ "Steely Dan secret wife". Now To Love. September 10, 2007. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ Smith, Giles (January 27, 1994). "A big hello from Hawaii". The Independent. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ McIver, Joel (September 4, 2017). "Walter Becker obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ Menconi, David (September 3, 2017). "Walter Becker, reeling in the years to the end". The News Observer. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Walter Becker". IMDb. Retrieved December 30, 2018.

- ^ "Walter Becker's Widow Says Steely Dan Co-Founder Died of Esophageal Cancer". November 15, 2017.

- ^ "Walter Becker's Widow Details Steely Dan Co-Founder's Swift Illness, Death". Rolling Stone. November 15, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ "Official Walter Becker | February 20, 1950 – Sep 3, 2017". Walter Becker. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Walter Becker's Widow Says Steely Dan Co-Founder Died of Esophageal Cancer". Variety. November 15, 2017. Retrieved November 15, 2017.

- ^ Saperstein, Pat (September 3, 2017). "Steely Dan's Donald Fagen on Walter Becker: 'Hysterically Funny, a Great Songwriter'". Variety. Retrieved September 23, 2017.

- ^ Lennon, Julian [@JulianLennon] (September 3, 2017). "So, so sad to hear this news.. SD played locally a few years ago, they were as amazing as ever... I asked to go" (Tweet). Retrieved September 3, 2017 – via Twitter.

- ^ Lukather, Steve [@stevelukather] (September 3, 2017). "Really sad to hear Walter Becker has passed... Steely Dan music touched me deep. My desert Island music. RIP Walter. Condolences Donald." (Tweet). Retrieved September 3, 2017 – via Twitter.

- ^ Darnielle, John [@mountain_goats] (September 3, 2017). "Steely Dan changed the way I understand music forever; I started writing songs under the name "the Mountain Goats" the same month 1/2" (Tweet). Retrieved September 3, 2017 – via Twitter.

- ^ Jones, Rickie Lee (September 3, 2017). "Read Rickie Lee Jones' Poignant Tribute to Steely Dan's Walter Becker". Rolling Stone. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ^ "Walter Becker Way". Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ Perlman, Michael (November 2018). "Walter Becker Way Unveiled in Forest Hills". Rego-Forest Preservation Council. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ Jones, Chris (July 16, 2008). "BBC Music Review". BBC. Retrieved September 3, 2017.

- ^ "Discography, guest appearances, production". walterbecker.com. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

- ^ "Walter Becker | Credits | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved October 8, 2017.

- ^ "Walter Becker". Discogs. August 17, 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

External links edit

- Official website and companion media website www.walterbeckermedia.com

- Walter Becker at AllMusic

- Walter Becker discography at Discogs

- Google (August 24, 2023). "Walter Becker Way" (Map). Google Maps. Google. Retrieved August 24, 2023.