Sempad the Constable (also Smpad and Smbat; Armenian: Սմբատ Սպարապետ, romanized: Smbat Sparapet or Սմբատ Գունդստաբլ, Smbat Gundstabl; 1208–1276) was a noble Cilician Armenia. He was an older brother of King Hetoum I. He was an important figure in Cilicia, acting as a diplomat, judge, and military officer, holding the title of Constable or Sparapet, supreme commander of the Armenian armed forces. He was also a writer and translator, especially known for providing translations of various legal codes, and the creation of an important account of Cilician history, called in French the Chronique du Royaume de Petite Armenie (Chronicle of the Kingdom of Little Armenia). He fought in multiple battles, such as the Battle of Mari, and was trusted by his brother King Hetoum to be a key negotiator with the Mongol Empire.

Biography edit

At the time of Sempad's birth there were two key dynasties in Cilicia, the Rubenids and the Hetoumids, and he was related to both. Sempad was the son of Constantine of Baberon and Partzapert (third cousin of Leo II of Armenia). Other siblings included John the Bishop of Sis, Ochine of Korykos, Stephanie (later wife of King Henry I of Cyprus), and Hetoum, who became co-ruler in 1226. The earlier ruler had been Queen Isabella of Armenia, who was married to Philip, son of Bohemond IV of Antioch. Constantine arranged for Philip to be murdered in 1225, and forced Isabella to then marry his son Hetoum on June 4, 1226, making him the co-ruler, and then sole ruler after Isabella's death in 1252.

Historical context edit

Cilicia was a Christian country, that had ties to Europe and the Crusader States, and fought against the Muslims for control of the Levant. The Mongols were also a threat, as Genghis Khan's Empire had been steadily pushing westward in its seemingly unstoppable advance. The Mongols had a deserved reputation for ruthlessness, giving new territories one opportunity to surrender, and if there was resistance, the Mongols moved in and slaughtered the local population.

In 1243, Sempad was part of the embassy to Caesarea, where he negotiated with the Mongol leader Baiju. In 1246 and again in 1259, Sempad was in charge of organizing the defense of Cilicia against the invasion of the Sultanate of Rum. In 1247, when King Hetoum I decided that his wisest course of action was to peacefully submit to the Mongols, Sempad was sent to the Mongol court in Karakorum.[2] There, Sempad met Kublai Khan's brother Möngke Khan, and made an alliance between Cilicia and the Mongols, against their common enemy the Muslims.[3] The nature of this relationship is described differently by various historians, some of whom refer to it as an alliance, while others describe it as a submission to Mongol overlordship, making Armenia a vassal state.[4] Historian Angus Donal Stewart, in Logic of Conquest, described it as, "The Armenian king saw alliance with the Mongols – or, more accurately, swift and peaceful subjection to them – as the best course of action."[5] Armenian military leaders were required to serve in the Mongol army, and many of them perished in Mongol battles.[6]

During his 1247-1250[7] visit to the Mongol court, Sempad received a relative of the Great Khan as a bride. He had a son with her, named Vasil Tatar,[8] who would later be captured by the Mamluks at the Battle of Mari in 1266.[9]

Sempad returned to Cilicia in 1250, though he returned to Mongolia in 1254, accompanying King Hetoum on his own visit to the court of the Great Khan, Möngke.

On the death of his father, Sempad became Baron of Papeŕōn (Çandır Castle) and resided in its small, but lavish baronial palace.[10]

Sempad died in 1276 either in the Second Battle of Sarvandikar, fighting against the Mamluks of Egypt, or against an invasion of the Turcomans from Marash. The Armenians won the battle, but Sempad and several other barons were lost.[11][12]

Judge edit

Sempad was a member of the Armenian supreme court, the Verin or Mec Darpas, which examined government policies and the legal codes. He created a translation of the Assizes of Antioch (a legal code) from French, and also created in Middle Armenian a Datastanagirk' (codex), which was based on and adapted from the earlier work of Mkhitar Gosh.[13]

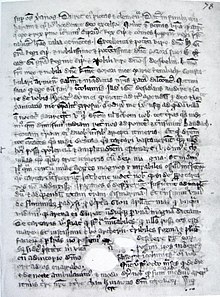

Writer edit

Sempad is best known for providing eyewitness written accounts of his era. He wrote the "Chronique du Royaume de Petite Arménie" (History of the Kingdom of Little Armenia) which begins around 951/952, and ends in 1274, two years before his death. He worked from older Armenian, Syriac, Christian, and possibly Byzantine sources, as well as from his own observations. Sempad's writings are considered a valuable resource by historians, although some have criticized them as unreliable, as Sempad was often writing for reasons of propaganda rather than history.[14][15]

Multiple translations exist of the work, in varying levels of completeness. According to historian Angus Donal Stewart, there are both French and English translations, which cover the period up until the 1270s.[16] In the 19th century, it was translated by Eduard Dulaurier and published in Receuil des Historiens des Croisades, Historiens Armeniens I, together with some other continuation excerpts by an anonymous author which cover the period after Sempad's death, up through the 1330s. This edition also includes excerpts from the work of Nerses Balients, who was writing in the later fourteenth century.[16][17]

Sempad was enthusiastic about his travel to the Mongol realm, which lasted between 1247 and 1250.[18] He sent letters to Western rulers of Cyprus and the Principality of Antioch, describing a Central Asian realm of oasis with many Christians, generally of the Nestorian rite.[19]

On February 7, 1248, Sempad sent a letter from Samarkand to his brother-in-law Henry I, king of Cyprus (who was married to Sempad's sister Stephanie (Etienette):[20]

"We have found many Christians throughout the land of the Orient, and many churches, large and beautiful.. The Christians of the Orient went to the Khan of the Tartars who now rules (Güyük), and he received them with great honour and gave them freedom and let it know everywhere that no-one should dare antagonize them, be it in deeds or in words."

— Letter from Sempad to Henry I.[21]

One of Sempad's letters was read by Louis IX of France during his 1248 stay in Cyprus, which encouraged him to send ambassadors to the Mongols, in the person of the Dominican André de Longjumeau, who went to visit Güyük Khan.

Notes edit

- ^ (in French) Mutafian. Le Royaume Armenien de Cilicie, p. 66

- ^ Edwards, p.9

- ^ Bournotian, p. 100. "Smbat met Kubali's brother, Mongke Khan and in 1247, made an alliance against the Muslims."

- ^ Weatherford, p. 181

- ^ Stewart, Logic of Conquest, p. 8. "The Armenian king saw alliance with the Mongols - or, more accurately, swift and peaceful subjection to them -- as the best course of action."

- ^ Bournotian, p. 109

- ^ Stewart, p. 35

- ^ Luisetto, p.122, who references introduction and notes in Gérard Dédéyan La Chronique attribuée au Connétable Sempad, 1980

- ^ Stewart, p. 49

- ^ Edwards, p.102-110; pls.53a-56b, 292b-295a

- ^ Mutafian, p. 61

- ^ Stewart, p. 51

- ^ Dictionary of the Middle Ages

- ^ Little, An Introduction to Mamluk Historiography

- ^ Angus Donal Stewart, Armenian Kingdom

- ^ a b Stewart, p. 22

- ^ Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Historiens Arméniens I, Chronique du Royaume de Petite Arménie, p. 610 et seq.

- ^ Grousset, p.529, Note 273

- ^ (in French) Richard. Histoire des Croisades, p. 376

- ^ Grousset, p. 529, note 272

- ^ Extract quoted in Grousset, p. 529

References edit

Primary sources edit

- Sempad the Constable, Chronique du Royaume de Petite Armenie, edition and French translation by Duraulier, in Recueil des Historiens des Croisades, Historiens Armeniens I, French translation: p. 610 et seq.; Russian translation and commentary by Galstian in Смбат спарапет. Летопись, Erevan 1974.

- Assises d'Antioche, French translation by Leon Alishan, of Sempad's Armenian translation of the now-lost Old French original

Secondary sources edit

- Bournoutian, George A. (2002). A Concise History of the Armenian People: From Ancient Times to the Present. Mazda Publishers. ISBN 1-56859-141-1.

- Edwards, Robert W. (1987). The Fortifications of Armenian Cilicia: Dumbarton Oaks Studies XXIII. Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. ISBN 0-88402-163-7.

- Luisetto, Frédéric (2007). Arméniens et autres Chrétiens d'Orient sous la domination mongole. Geuthner. ISBN 978-2-7053-3791-9.

- Maksoudian, Krikor H., American Council of Learned Societies (1989). "Smbat Sparapet". Dictionary of the Middle Ages. Charles Scribner's Sons, reproduced in History Resource Center.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mutafian, Claude (2001) [1993]. Le Royaume Armenien de Cilicie (in French). CNRS Editions. ISBN 2-271-05105-3.

- Richard, Jean (1996). Histoire des Croisades. Fayard. ISBN 2-213-59787-1.

- Stewart, Angus Donal (2001). The Armenian Kingdom and the Mamluks: War and diplomacy during the reigns of Het'um II (1289-1307). BRILL. ISBN 90-04-12292-3.

- Weatherford, Jack (2004). Genghis Khan and the Making of the Modern World. Three Rivers Press. ISBN 0-609-80964-4.

External links edit

- Smbat Sparapet's Chronicle Translated by Robert Bedrosian.

- English translation of the Chronicle - mirror if main site is unavailable

- Letter of Smbat Constable to King Henry I of Cyprus, ca. 1248