Ton Satomi (里見 弴, Satomi Ton, July 14, 1888 - January 21, 1983) is the pen-name of Japanese author Hideo Yamanouchi (山内英夫, Yamanouchi Hideo).[1] Satomi was known for the craftsmanship of his dialogue and command of the Japanese language. His two elder brothers, Ikuma Arishima and Takeo Arishima, were also authors.

Ton Satomi | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

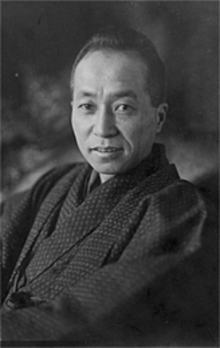

Ton Satomi in 1927 | |||||

| Native name | 里見 弴 | ||||

| Born | Hideo Yamanouchi 14 July 1888 Yokohama, Japan | ||||

| Died | 21 January 1983 (aged 94) Kamakura, Kanagawa, Japan | ||||

| Resting place | Kamakura Reien Public Cemetery, Kamakura, Japan | ||||

| Occupation | Writer | ||||

| Genre | Novels, short stories | ||||

| Literary movement | Shirakaba | ||||

| Notable awards | Kikuchi Kan Award (1940) Yorimuri Prize (1956, 1971) Order of Culture (1959) | ||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 里見 弴 | ||||

| Hiragana | さとみ とん | ||||

| |||||

Early life edit

Satomi Ton was born in Yokohama into the wealthy Arishima family, but was later legally adopted by his mother's family, thus inheriting their surname of Yamanouchi. He was educated at the Gakushuin Peers' School, where he became interested in literature, and briefly attended Tokyo Imperial University, but left in 1910 without graduating.[2]

Literary career edit

Through his brother Ikuma Arishima, he became acquainted with other alumni authors from Gakushuin, including Naoya Shiga and Saneatsu Mushanokōji. They formed a group named after their literary magazine Shirakaba, which was first published in 1910. Satomi claimed that he decided on his pen-name by picking out names at random from a telephone directory. In his early years, he was a frequent visitor to Yoshiwara together with Naoya Shiga, but he later married a former geisha from Osaka, Masa Yamanaka, and later novelized the story in the novels Kotoshidake (今年竹) and Tajō Busshin (多情仏心). Although he wrote some works in 1913 and 1914, Satomi’s literary debut was in 1915 in Chūōkōron. Satomi became a disciple of Kyōka Izumi after his works came to the attention of the older novelist.[2]

Satomi strove to remain aloof from any particular literary clique or political school throughout his career. He was a prolific author known for his autobiographical works and promotion of purely literary values. In the West he is largely known for Tsubaki ("Camellia"), a disturbing short story written after the Great Kantō earthquake of 1923, which came a few months after the suicide of his brother Takeo Arishima. From 1932, he worked as an instructor at Meiji University. He was awarded the Kikuchi Kan Prize in 1940.

In 1945, together with Yasunari Kawabata, he created the Kamakura Bunko. He was made a member of the Japan Art Academy in 1947. In 1958, his novel Higanbana (Equinox Flower) was made into a movie by Yasujirō Ozu, starring Kinuyo Tanaka.

In 1959, Satomi received the Order of Culture from the Japanese government.[2] In 1960, Satomi published Late Autumn, which was later made into a movie by Yasujirō Ozu starring Setsuko Hara. He was awarded the Yomiuri Prize in 1956 and in 1971.

He lived in Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture from 1924 until his death, and often socialized with the other literati residing in that city. With the establishment of the Shochiku movie studios in Ofuna, north of Kamakura, he also collaborated with film director Yasujirō Ozu on numerous movie scripts.

Satomi died in 1983. His grave is located at the Kamakura Reien Public Cemetery.

Major works edit

- Zen Shin Aku Shin ("Good Heart Evil Heart")

- Tajo Busshin ("The Compassion of Buddha", 1922–1923)

- Anjo Ke no Kyodai ("The Anjo Brothers")

- Gokuraku Tombo ("A Carefree Fellow", 1961)

See also edit

References edit

- Flowler, Edward. The Rhetoric of Confession: Shishosetsu in Early Twentieth-Century Japanese Fiction. University of California Press (1992). ISBN 0-520-07883-7

- Keene, Donald. Dawn to the West. Columbia University Press; 2nd Rev Ed edition (1998). ISBN 0-231-11435-4

- Morris,Ivan. Modern Japanese Stories: An Anthology. Tuttle Publishing (2005). ISBN 0-8048-3336-2

Notes edit

- ^ Mortimer, Maya (2002). Meeting the Sensei: The Role of the Master in Shirakaba. Brill. ISBN 9004116559. page 5

- ^ a b c Miller, Scott J (2009). The A to Z of Modern Japanese Literature and Theater. Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 978-0810876156. page 107