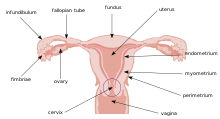

Primary fallopian tube cancer (PFTC), also known as tubal cancer, is a malignant neoplasm that originates from the fallopian tube.[1][3] Along with primary ovarian and peritoneal carcinomas, it is grouped under epithelial ovarian cancers, cancers of the ovary that originate from a fallopian tube precursor.[4][5]

| Primary fallopian tube cancer | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specialty | Oncology, gynaecology |

| Symptoms | Early: Vague, none[1][2] Later: Abnormal vaginal bleeding, abdominal distension, blood stained watery vaginal discharge, pelvic pain, loss of appetite, weight loss, feel full[1][2] |

| Diagnostic method |

|

| Differential diagnosis | Ovarian cancer, peritoneal cancer[1] |

Signs and symptoms edit

In the early stages, symptoms are typically vague.[2] Other symptoms may include abnormal vaginal bleeding, blood stained watery vaginal discharge, pelvic pain, or abdominal distension.[2] An affected person may feel full or have weight loss.[1]

Vaginal discharge in fallopian tube carcinoma results from intermittent hydrosalphinx, also known as hydrops tubae profluens.[6]

Pathology edit

The most common cancer type within this disease is adenocarcinoma; in the largest series of 3,051 cases as reported by Stewart et al. 88% of cases fell into this category.[7] According to their study, half of the cases were poorly differentiated, 89% unilateral, and the distribution showed a third each with local disease only, with regional disease only, and with distant extensions. Rarer forms of tubal neoplasm include leiomyosarcoma, and transitional cell carcinoma.

As the tumor is often enmeshed with the adjacent ovary, it may be the pathologist and not the surgeon who determines that the lesion is indeed tubal in origin.

Secondary tubal cancer usually originates from cancer of the ovaries, the endometrium, the GI tract, the peritoneum, and the breast.

Diagnosis edit

Diagnosis is by blood tests, medical imaging, and pathologic assessment of fallopian tissue.[1] Blood tests include Ca-125 and CBC.[1] Imaging includes transvaginal and abdominal ultrasound, CT scan, and MRI.[2] Pathologic assessment may include SEE-FIM Protocol.[1] A pelvic mass may be detected on a routine gynecologic examination.[2] It may be found at an early stage when removing the tubes and ovaries as a preventive measure.[1]

Differential edit

Ovarian and peritoneal cancers may present in a similar way.[1]

Staging edit

| Stage | Definition |

|---|---|

| Stage 0 | Carcinoma in situ[1] |

| Stage I | Growth limited to fallopian tubes[1] |

| Stage II | Growth involving one or both fallopian tubes with extension to pelvis[1] |

| Stage III | Tumor involving one or both fallopian tubes with spread outside pelvis[1] |

| Stage IV | Growth involving one or more fallopian tubes with distant metastases[1] |

Treatment edit

The initial approach to tubal cancer is generally surgical, and similar to that of ovarian cancer. As the lesion will spread first to the adjacent uterus and ovary, a total abdominal hysterectomy is an essential part of this approach, removing the ovaries, the tubes, and the uterus with the cervix. Also, peritoneal washings are taken, the omentum is removed, and pelvic and paraaortic lymph nodes are sampled. Staging at the time of surgery and pathological findings will determine further steps. In advanced cases when the cancer has spread to other organs and cannot be completely removed, cytoreductive surgery is used to lessen the tumor burden for subsequent treatments. Surgical treatments are typically followed by adjuvant, usually platinum-based, chemotherapy.[8][9] Radiation therapy has been applied with some success to patients with tubal cancer for palliative or curative indications.[10]

Prognosis edit

Five-year survival rate is around 65%, though may range from 30% to 92% depending on stage at diagnosis and the amount of tumor remaining after surgery.[1][4]

Frequency edit

Tubal cancer is thought to be a relatively rare primary cancer among women, accounting for 1 to 2 percent of all gynecologic cancers,[11] In the US, tubal cancer had an incidence of 0.41 per 100,000 women from 1998 to 2003.[7] Demographic distribution is similar to that of ovarian cancer, and the highest incidence is found in white, non-Hispanic women aged 60–79.[7] However, recent evidence suggests tubal cancer to be much more frequent.[1]

Evidence is accumulating that individuals with mutations of BRCA1 and BRCA2 are at higher risk for the development of PFTC.[12][13]

History edit

The first descriptions were made by Renaud in 1847 and Ernst Gottlob Orthmann in 1888.[14]

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Ferri, Fred F. (2024). "Fallopian tube cancer". Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2024. Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 568.e5. ISBN 978-0-323-75576-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Fallopian tube cancer". www.cancerresearchuk.org. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board, ed. (2020). "4. Tumours of the fallopian tube: introduction". Female genital tumours: WHO Classification of Tumours. Vol. 4 (5th ed.). Lyon (France): International Agency for Research on Cancer. p. 216. ISBN 978-92-832-4504-9.

- ^ a b Stasenko, Marina; Fillipova, Olga; Tew, William P. (July 2019). "Fallopian Tube Carcinoma". Journal of Oncology Practice. 15 (7): 375–382. doi:10.1200/JOP.18.00662. ISSN 1554-7477.

- ^ Rashid, Sameera; Arafah, Maria A.; Akhtar, Mohammed (1 May 2022). "The Many Faces of Serous Neoplasms and Related Lesions of the Female Pelvis: A Review". Advances in Anatomic Pathology. 29 (3): 154–167. doi:10.1097/PAP.0000000000000334. ISSN 1533-4031. PMC 8989637. PMID 35180738.

- ^ GOLDMAN JA, GANS B, ECKERLING B (November 1961). "Hydrops tubae profluens--symptom in tubal carcinoma". Obstet Gynecol. 18: 631–4. PMID 13899814.

- ^ a b c Stewart SL, Wike JM, Foster SL, Michaud F (2007). "The incidence of primary fallopian tube cancer in the United States". Gynecol. Oncol. 107 (3): 392–7. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.09.018. PMID 17961642.

- ^ Liapis A, Bakalianou K, Mpotsa E, Salakos N, Fotiou S, Kondi-Paffiti A (2008). "Fallopian tube malignancies: A retrospective clinical pathological study of 17 cases". J Obstet Gynaecol. 28 (1): 93–5. doi:10.1080/01443610701811894. PMID 18259909. S2CID 5351886.

- ^ Takeshima N, Hasumi K (2000). "Treatment of fallopian tube cancer. Review of the literature". Arch Gynecol Obstet. 264 (1): 13–9. doi:10.1007/pl00007475. PMID 10985612. S2CID 34114333.

- ^ Schray MF, Podratz KC, Malkasian GD (1987). "Fallopian tube cancer: the role of radiation therapy". Radiother. Oncol. 10 (4): 267–75. doi:10.1016/s0167-8140(87)80032-4. PMID 3444903.

- ^ UCSF. "Gynecologic Cancer: Fallopian Tube Cancer". accessed 08-14-2008

- ^ BRCA mutations link to tubal cancer, accessed 08-14-2008

- ^ Piek, J. M. J. (2004). Hereditary serous ovarian carcinogenesis, a hypothesis (PhD thesis). Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. hdl:1871/9013. ISBN 9064646406.

- ^ Laury, Anna; Huang, Eric C.; Crum, Christopher P.; Hecht, Jonathan (2013). "7. Peritoneal and tubal serous carcinoma". In Deligdisch, Liane; Kase, Nathan G.; Cohen, Carmel J. (eds.). Altchek's Diagnosis and Management of Ovarian Disorders (3rd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 111–120. ISBN 978-1-107-01281-3.