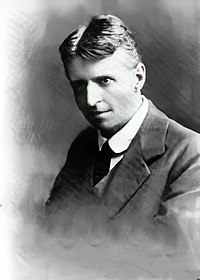

Otto Hans Adolf Gross (17 March 1877 – 13 February 1920) was an Austrian psychoanalyst. A maverick early disciple of Sigmund Freud, he later became an anarchist and joined the utopian Ascona community.

Otto Gross | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Otto Hans Adolf Gross 17 March 1877 |

| Died | 13 February 1920 (aged 42) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychoanalysis |

His father Hans Gross was a judge turned pioneering criminologist. Otto initially collaborated with him, and then turned against his determinist ideas on character.[1]

A champion of an early form of anti-psychiatry and sexual liberation, he also developed an anarchist form of depth psychology (which rejected the civilising necessity of psychological repression proposed by Freud). He adopted a modified form of the proto-feminist and neo-pagan theories of Johann Jakob Bachofen,[2] with which he attempted to return civilization to a 'golden age' of non-hierarchy. Gross was ostracized from the larger psychoanalytic movement, and was not included in histories of the psychoanalytic and psychiatric establishments. He died in poverty.

Greatly influenced by the philosophy of Max Stirner[3] and Friedrich Nietzsche and the political theories of Peter Kropotkin, he in turn influenced D. H. Lawrence (through Gross's affair with Frieda von Richthofen), Franz Kafka and other artists, including Franz Jung and other founders of Berlin Dada. His influence on psychology was more limited. Carl Jung claimed his entire worldview changed when he attempted to analyse Gross and partially had the tables turned on him.[4]

He became addicted to drugs in South America where he served as a naval doctor. He was hospitalized several times for drug addiction, sometimes losing his guardianship of himself to his father in the process.[5] As a Bohemian drug user from youth, as well as an advocate of free love, he is sometimes credited as a founding grandfather of 20th-century counterculture.

Contributions to depth psychology edit

Carl Jung credited Gross with having described two general types – "inferiority with shallow consciousness" and "inferiority with contracted consciousness" – that very closely resemble what Jung described as the extraverted feeling and introverted thinking types a decade later. Despite having issues with Gross's theoretical assumptions of a secondary cell function and the "individual" nature of a person's passion, Jung credited Gross with major advances in typological and psychological theory.

In his 1913 work A Contribution to the Study of Psychological Types, Jung devoted a paragraph to Otto Gross's contributions.

The relation he [Gross] established between manic-depressive insanity and the type with a shallow consciousness shows that we are dealing with extraversion, while the relation between the psychology of the paranoiac and the type with a contracted consciousness indicates the identity with introversion (Jung, [1921] 1971: par. 879).

In Jung's monumental work Psychological Types, all of chapter VI, The Type Problem in Psychopathology, analyzes and reconciles Gross's theory as expressed in Die zerebrale Sekundärfunktion (1902) and Über psychopathische Minderwertigkeit (1903).

Gross deserves full credit for being the first to set up a simple and consistent hypothesis to account for this [the extraverted] type (Jung, [1921] 1971: par. 466).

In fiction edit

Otto Gross, played by Vincent Cassel, is one of the characters in the 2011 film A Dangerous Method, which focused on the relations among Jung, Sabina Spielrein and Freud. In the film, Gross considerably influenced Jung's theories as well as Jung's private life, encouraging Jung to shed his inhibitions and start an extra-marital affair with Spielrein, Jung's patient who became his colleague and one of the first female psychoanalysts.

According to Brenda Maddox, Otto Gross "talked all the time — even, if his portrait in D.H. Lawrence's novel Mr Noon is accurate, during sexual intercourse."[6]

Death edit

Gross died of pneumonia, possibly related to drug addiction, in Berlin on 13 February 1920, after being found in the street, near-starved and freezing.[7]

Notes edit

- ^ Ronald Hayman, A Life of Jung (1999), p. 99.

- ^ Hayman, p. 101.

- ^ Bernd A. Laska, Otto Gross zwischen Max Stirner und Wilhelm Reich, In: Raimund Dehmlow and Gottfried Heuer, eds.: 3. Internationaler Otto-Gross-Kongress, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, München. Marburg, 2003, pp. 125–162, ISBN 3-936134-06-5 LiteraturWissenschaft.de.

- ^ Hayman, p. 102.

- ^ Heuer, Gottfried. Otto Gross, 1877-1920, Biographical Survey.

- ^ Maddox, Brenda, Freud's Wizard: The Enigma of Ernest Jones, London: John Murray (Publishers), 2006, p. 55.

- ^ Heuer, Gottfried. Otto Gross, 1877-1920, Biographical Survey.

References edit

- Jung, C.G. (1971 [1921]). Psychological Types, Collected Works, Volume 6, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01813-8.

- Le Rider, Jacques (1993). Modernity and Crises of Identity: Culture and Society in Fin-de-siecle Vienna. Verlag: Polity Press. ISBN 0-7456-0970-8.

External links edit

- The responsibility of the Otto Gross Society is to research the social impact of the activity of the doctor, scientist, and revolutionary Otto Gross; to depict his influence on the development of intellectual history in the 20th century; and to make the results of this work publicly accessible through publications and meetings of all kinds.

- Gross, Otto Die Zerebrale Sekundärfunction. Leipzig : F. C. W. Vogel, 1902. Otto Gross Society