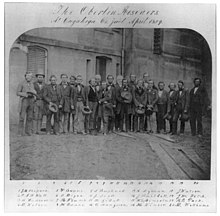

The Oberlin–Wellington Rescue of 1858 in was a key event in the history of abolitionism in the United States. A cause celèbre and widely publicized, thanks in part to the new telegraph, it is one of the series of events leading up to Civil War.

John Price, an escaped slave, was arrested in Oberlin, Ohio, under the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. To avoid conflict with locals, whose abolitionism was well known, the U.S. marshal and his party took him to the first train stop out of Oberlin heading south: Wellington. Rescuers from Oberlin followed them to Wellington, took Price by force from the marshal and escorted him back to Oberlin, from where he headed via the Underground Railroad to freedom in Canada.

Thirty-seven rescuers were indicted, but as a result of state and federal negotiations, only two were tried in federal court. The case received national attention, and defendants argued eloquently against the law. When rescue allies went to the 1859 Ohio Republican convention, they added a repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law to the party platform. The rescue and continued activism of its participants kept the issue of slavery as part of the national discussion.[1]

- Northwest Ordinance

- Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

- End of Atlantic slave trade

- Missouri Compromise

- Tariff of 1828

- Nat Turner's Rebellion

- Nullification crisis

- End of slavery in British colonies

- Texas Revolution

- United States v. Crandall

- Gag rule

- Commonwealth v. Aves

- Murder of Elijah Lovejoy

- Burning of Pennsylvania Hall

- American Slavery As It Is

- United States v. The Amistad

- Prigg v. Pennsylvania

- Texas annexation

- Mexican–American War

- Wilmot Proviso

- Nashville Convention

- Compromise of 1850

- Uncle Tom's Cabin

- Recapture of Anthony Burns

- Kansas–Nebraska Act

- Ostend Manifesto

- Bleeding Kansas

- Caning of Charles Sumner

- Dred Scott v. Sandford

- The Impending Crisis of the South

- Panic of 1857

- Lincoln–Douglas debates

- Oberlin–Wellington Rescue

- John Brown's raid on Harpers Ferry

- Virginia v. John Brown

- 1860 presidential election

- Crittenden Compromise

- Secession of Southern states

- Peace Conference of 1861

- Corwin Amendment

- Battle of Fort Sumter

Precedent

editOn March 5, 1841, a group described by local newspapers as supposed "fanatical abolition anarchists" from Oberlin, using saws and axes, freed two captured fugitive slaves from the Lorain County jail.[2]

Events

editOn September 13, 1858, a runaway slave named John Price, from Maysville, Kentucky, was arrested by a United States marshal in Oberlin, Ohio. Under the Fugitive Slave Law, the federal government assisted slave owners in reclaiming their runaway slaves, and local officials were required to assist. The marshal knew that many Oberlin residents were abolitionists, and the town and college were known for their radical anti-slavery stance. To avoid conflict with locals and to quickly get the slave to Columbus and en route to the slave's owner in Kentucky, the marshal quickly took Price to nearby Wellington, Ohio, to board a train.

As soon as residents heard of the marshal's actions, a group of men rushed to Wellington. They joined like-minded residents of Wellington and attempted to free Price, but the marshal and his deputies took refuge in a local hotel. After peaceful negotiations failed, the rescuers stormed the hotel and found Price in the attic. The group immediately returned Price to Oberlin, where they hid him in the home of James Harris Fairchild, a future president of Oberlin College. A short time later, they took Price to Canada, terminus of the Underground Railroad, where there was no slavery and fugitives were safe. Nothing is known about Price's life in Canada.

Trial

editA federal grand jury brought indictments against 37 of those who freed Price. Professor Henry E. Peck was indicted, and twelve of the rescuers indicted were free blacks, among them Charles Henry Langston, who had helped ensure that Price was taken to Canada rather than released to the authorities.[1] Charles and his brother John Mercer Langston were both Oberlin College graduates, and led the Ohio Anti-Slavery Society in 1858. They both were politically active all their lives, Charles in Kansas and John taking leadership roles in state and national politics, in 1888 becoming the first African-American to be elected to the US Congress from Virginia.[3]

On January 11, the 37 celebrated at a dinner in the Palmer House in Oberlin. In a lengthy article about it in a Cleveland paper, the toasts were published.[4]

Feelings ran high in Ohio in the aftermath of Price's rescue. When the federal grand jury issued its indictments, state authorities arrested the federal marshal, his deputies, and other men involved in John Price's detention. After negotiations, state officials agreed to release the arresting officials, while federal officials agreed to drop the charges and release 35 of the men indicted.[5]

Simeon M. Bushnell, a white man, and Charles H. Langston were the only two who went to trial.[3] Four prominent local attorneys—Franklin Thomas Backus, Rufus P. Spalding, Albert G. Riddle, and Seneca O. Griswold—acted for the defense. The jurors were all known Democrats. After they convicted Bushnell, the same jury was called to try Langston, despite his protests that they could not be impartial.

Langston gave a speech in court that was a rousing statement of the case for abolition and for justice for colored men. He closed with these words:

But I stand up here to say, that if for doing what I did on that day at Wellington, I am to go to jail six months, and pay a fine of a thousand dollars, according to the Fugitive Slave Law, and such is the protection the laws of this country afford me, I must take upon my self the responsibility of self-protection; and when I come to be claimed by some perjured wretch as his slave, I shall never be taken into slavery. And as in that trying hour I would have others do to me, as I would call upon my friends to help me; as I would call upon you, your Honor, to help me; as I would call upon you [to the District-Attorney], to help me; and upon you [to Judge Bliss], and upon you [to his counsel], so help me GOD! I stand here to say that I will do all I can, for any man thus seized and help, though the inevitable penalty of six months imprisonment and one thousand dollars fine for each offense hangs over me! We have a common humanity. You would do so; your manhood would require it; and no matter what the laws might me, you would honor yourself for doing it; your friends would honor you for doing it; your children to all generations would honor you for doing it; and every good and honest man would say, you had done right!

— Great and prolonged applause, in spite of the efforts of the Court and the Marshal to silence it.[6]

The jury also convicted Langston. The judge gave light sentences: Bushnell 60 days in jail and Langston 20.

Appeal

editBushnell and Langston filed a writ of habeas corpus with the Ohio Supreme Court, claiming that the federal court did not have the authority to arrest and try them because the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was unconstitutional. The Ohio Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the law by a three-to-two ruling. Although Chief Justice Joseph Rockwell Swan was personally opposed to slavery, he wrote that his judicial duty left him no choice but to acknowledge that an Act of the United States Congress was the supreme law of the land (see Supremacy Clause), and to uphold it.

Members of Ohio's abolitionist community were incensed. More than 10,000 people participated in a Cleveland rally to oppose the federal and state courts' decisions. Appearing with Republican leaders such as Gov. Salmon P. Chase and Joshua Giddings, John Mercer Langston was the sole black speaker that day.[3] Because of his decision, Chief Justice Swan failed to win reelection and his political career was ruined in Ohio.

Aftermath

editIn time, regional tensions over slavery, constitutional interpretation, and other factors led to the outbreak of the Civil War. The Oberlin-Wellington rescue is considered important as it not only attracted widespread national attention but occurred in a region of Ohio known for its Underground Railroad activity. Those who participated in the rescue and their allies continued to be active in Ohio and national politics. In 1859 those who attended the Ohio Republican convention succeeded in adding a repeal of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 to the Ohio party platform. The rescue and continued actions of its participants brought the issue of slavery into national discussion.[1]

Two participants in the Oberlin–Wellington Rescue—Lewis Sheridan Leary and John A. Copeland, along with Oberlin resident Shields Green—went on to join John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry in 1859. Leary was killed during the attack. Copeland and Green were captured and tried along with John Brown. They were convicted of treason and executed on December 16, 1859, two weeks after Brown.

See also

edit- Chatham Vigilance Committee, a related set of rescues with former graduates of Oberlin College

References

edit- ^ a b c Matt Lautzenheiser, "Book Review: Ronald M. Baumann, 'The 1858 Oberlin-Wellington Rescue: A Reappraisal' " Archived July 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Northern Ohio Journal of History, accessed Dec 15, 2008

- ^ "Abolitionism—Oberlin Negro Riot". Democratic Standard (Georgetown, Ohio). March 23, 1841. p. 2. Archived from the original on October 3, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2019 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c William and Aimee Cheek, "John Mercer Langston: Principle and Politics", in Leon F. Litwack and August Meier, eds., Black Leaders of the Nineteenth Century, University of Illinois Press, 1991, pp. 106–111

- ^ "'Felon Feast' at Oberlin". Cleveland Daily Leader (Cleveland, Ohio). January 13, 1859. p. 2 – via newspapers.com.

- ^ "Oberlin-Wellington Rescue Case" Archived 7 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Ohio History Central, 2008, accessed Dec 15, 2008

- ^ "Charles Langston's Speech in the Cuyahoga County Courthouse, May 1859" Archived 5 September 2008 at the Wayback Machine, Oberlin College, accessed Dec 15, 2008

Further reading

edit- Baumann, Roland. The 1858 Oberlin-Wellington Rescue: A Reappraisal (2003)

- Brandt, Nat. The Town that Started The Civil War (1990) (ISBN 0-8156-0243-X/BRTT)

- Shipherd, Jacob R. History of the Oberlin-Wellington Rescue (1859) (ISBN 0837127297 ) Available in full at OhioMemory.org

- Plumb, Ralph (April 22, 1888). "Congressman Plumb Tells the Story of the Oberlin Rescuers, of Who He Was One". St. Louis Globe-Democrat (St. Louis, Missouri). p. 32 – via newspapers.com.

External links

edit- Oberlin Heritage Center

- "An Account of the Trials of Simeon Bushnell and Charles Langston", by the Oberlin–Wellington Rescuers, 1859, Oberlin College

- "Charles Langston's Speech at the Cuyahoga County Courthouse, May 12, 1859", Oberlin College