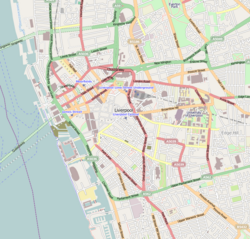

Liverpool Town Hall stands in High Street at its junction with Dale Street, Castle Street, and Water Street in Liverpool, Merseyside, England. It is recorded in the National Heritage List for England as a designated Grade I listed building, and described in the list as "one of the finest surviving 18th-century town halls".[1] The authors of the Buildings of England series refer to its "magnificent scale", and consider it to be "probably the grandest ...suite of civic rooms in the country", and "an outstanding and complete example of late Georgian decoration".[2]

| Liverpool Town Hall | |

|---|---|

Liverpool Town Hall at night | |

| Location | High Street, Liverpool, Merseyside, England |

| Coordinates | 53°24′26″N 2°59′30″W / 53.4071°N 2.9916°W |

| OS grid reference | SJ 342 905 |

| Built | 1754 |

| Rebuilt | 1802 |

| Architect | John Wood the Elder, John Foster, James Wyatt |

| Architectural style(s) | Georgian |

Listed Building – Grade I | |

| Designated | 28 June 1952 |

| Reference no. | 1360219 |

It is not an administrative building but a civic suite, Lord Mayor's parlour and Council chamber; local government administration is centred at the nearby Cunard Building. The town hall was built between 1749 and 1754 to a design by John Wood the Elder replacing an earlier town hall nearby. An extension to the north designed by James Wyatt was added in 1785. Following a fire in 1795 the hall was largely rebuilt and a dome designed by Wyatt was built. Minor alterations have subsequently been made. The streets surrounding its site have altered since its initiation, notably when viewed from Castle Street, the south-side, it appears as off-centre. This is because Water Street which ran to the junction with Dale Street, the west-east axis, was continuous and built up across the junction so that the town hall was not visible originally from that aspect. The structures were removed 150 years after this to expose the building from this position.

The ground floor contains the city's Council Chamber and a Hall of Remembrance for the Liverpool servicemen killed in the First World War. The upper floor consists of a suite of lavishly decorated rooms which are used for a variety of events and functions. Conducted tours of the building are arranged for the general public and the hall is licensed for weddings.

History edit

The first recorded town hall in Liverpool was in 1515 and it was probably a thatched building.[3] and was located in the block bounded by High Street, Dale Street & Exchange Street East. It was replaced in 1673 by a building slightly to the south of the present town hall. This town hall stood on "pillars and arches of hewen stone" and under it was the exchange for merchants and traders to carry out their business.[4]

Building of the present town hall began in 1749 on a site slightly to the north of its predecessor; its foundation stone was laid on 14 September. The architect was John Wood the Elder, who has been described as "one of the outstanding architects of the day".[4] It was completed and opened in 1754. The ground floor acted as the exchange, and a council room and other offices were on the upper floor.[4] The ground floor had a central courtyard surrounded by Doric colonnades but it was "dark and confined, and the merchants preferred to transact business in the street outside".[5] Above the building was a large square dome with a cupola.[5] In 1769 the building was provided with a turret clock manufactured by Joseph Finney of Liverpool.[6]

The town hall was bombarded by striking seamen during the 1775 Liverpool Seamen's Revolt.[7]

The very last act of the American Civil War was when Captain Waddell walked up the steps of the town hall in November 1865 with a letter to present to the mayor surrendering his vessel, the CSS Shenandoah, to the British government.[8]

Improvements began in 1785 with an extension to the north designed by James Wyatt. Buildings close to the west and north sides were demolished, and John Foster prepared plans for the west façade. In 1786 Wood's square dome was demolished and plans were made by Wyatt for a new dome over the central courtyard. In 1795, before the new dome was built, the hall was seriously damaged by a fire. Wyatt's north extension was not significantly damaged, but Wood's original building was gutted. The building was reconstructed and Wyatt's new dome was added. The work was supervised by Foster and completed in 1802. Under the dome the central courtyard was replaced with a hall containing a staircase. In 1811 a portico was added to the south side.[9] The construction and decoration of the interior was completed by about 1820.[1]

In 1857 a telegraph wire was laid from the Observatory at Waterloo Dock to the Town Hall (at the suggestion of the Director of the Observatory, John Hartnup) with the intention of using 'galvanic current' to transmit a time signal from the 'normal clock' in the observatory to the turret clock in the dome of the Town Hall, so as to ensure that it displayed accurate time.[10] This was achieved through an invention of a Mr R. L. Jones of Chester: by replacing the pendulum bob of the clock with a hollow electro-magnetic coil (in the manner of Bain's electric pendulum) and connecting it to the telegraph wire (which provided a regular pulse of current at one second intervals from the Observatory clock), the two clocks became synchronised; and so 'was seen the curious spectacle of a great clock with works nearly 100 years old keeping time with astronomical accuracy'.[11] This was the first application of clock network technology to a large public clock; it was later applied to (among others) the clock in the Victoria Tower, and the two were thenceforth heard to strike the hour simultaneously.[12]

In 1881 an attempt to blow up the town hall by the Fenians was aborted.[3] Between 1899 and 1900 the portico on the north face was rebuilt and extended,[9] and the northern extension was enlarged to form a recess in the Council Chamber for the Lord Mayor's chair, this was the work of the borough surveyor Thomas Shelmerdine.[13] In 1921 a room on the ground floor was made into the Hall of Remembrance to commemorate the military men from Liverpool who died in the First World War.[14] Part of the building was damaged in the Liverpool Blitz of 1941; this restored after the end of the Second World War.[3] Further restoration was carried out between 1993 and 1995.[15] Between 2014 and 2015 the exterior of the building was renovated as part of a £400,000 project. The work included repairing bomb damage from the 1941 Blitz and cleaning the sandstone from the effects of pollution.[16]

Architecture edit

Exterior edit

The town hall is built of stone with a slate roof and a lead dome.[1] Its plan consists of a rectangle with a portico extending to the south and Wyatt's rectangular extension to the north. The extension is slightly narrower than the rest of the building, and also has a projecting portico.[5] The building has two storeys and a basement; the stonework of the basement and lower storey is rusticated. The south face, overlooking Castle Street, has nine bays. Its central three bays are occupied by the portico. This has three rounded arches on the ground floor, and four pairs of Corinthian columns in the upper storey surrounding a balcony. The east and west faces also have nine bays in the original part of the building, plus an additional three bays to the north on Wyatt's extension. The middle three bays of the nine original bays project slightly forward and are surmounted by a pediment. The roof of the north face is higher than that of the main building. This face has five bays, with a central portico of three bays. On its first floor are four pairs of Corinthian columns and standing on the roof above these are four statues dating from 1792 by Richard Westmacott;[17] these statues have been moved from the Irish Houses of Parliament.[1] Above the upper storey windows on all faces are panels containing carvings, some of which relate to Liverpool's foreign trade.[5] The dome stands on a high drum supported on Corinthian columns. Around the base of the dome are four clock faces, each of which is supported by a lion and unicorn.[9] On the summit of the dome is a statue, representing Minerva. It is 10 feet (3 m) high and was designed by John Charles Felix Rossi.[15]

Interior edit

Ground floor edit

The main door in the south face leads to the Vestibule or Entrance Hall. It has a floor of encaustic tiles which include depictions of the arms of Liverpool and the liver bird.[18]

The room is panelled and on the east side is a large wooden fireplace containing 17th century Flemish carvings. It has a groin-vaulted ceiling, and in the lunettes are murals painted in 1909 by J.H. Amschewitz, depicting events in Liverpool's history; King John creating Liverpool a free port (west wall); Industry and Peace (North Wall); Liverpool the centre of commerce (east wall); Education and Progress (South wall).[19] Below these are brass tablets containing the names of the freemen of Liverpool. Also in the entrance hall are bardic chairs from the two Eisteddfods held in the city.[13][20]

At the rear of the ground floor in Wyatt's extension is the Council Chamber. This has mahogany-panelled walls and can seat 160 people.[13][21] Adjacent to the Council Chamber is the Hall of Remembrance. On its wall are panels bearing the names of the military men who lost their lives in the First World War, and eight murals painted by Frank O. Salisbury in 1923.[13][14]

In the centre of the ground floor is the Staircase Hall described in the Buildings of England series as "one of the great architectural spaces of Liverpool".[13] A broad staircase rises between two pairs of Corinthian columns to a half-landing, and narrower flights climb from that on each side to the upper floor. On the ground floor on each side of the staircase are display cabinets holding the city's silver. On the half-landing is a statue of George Canning dated 1832 by Francis Chantrey, and hanging on the wall above this is a portrait of Queen Elizabeth II by Sir Edward Halliday.[18]

Above the staircase the dome is carried by four pendentives; it rises to a height of 106 feet (32 m) and its interior is coffered. Around the base of the dome is inscribed Liverpool's motto, "Deus Nobis Haec Otia Fecit", and in the pendentives are paintings dated 1902 by Charles Wellington Furse depicting scenes of dock labour.[22][23]

Upper floor edit

| Upper floor plan | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Central Reception Room | B | West Reception Room | |||

| C | Dining Room | D | Large Ballroom | |||

| E | Small Ballroom | F | East Reception Room | |||

All the rooms on this floor are designed for entertainment and they have connecting doors that allow for a complete circuit of the floor. The middle room on the south side of the building is the Central Reception Room. It has a circular ceiling with pendentives, and plasterwork in neoclassical style designed by Francesco Bernasconi.[24] The room leads to the balcony overlooking Castle Street.[25] A door to the right leads to the West Reception Room, with a segmented-vaulted ceiling; it contains a marble chimneypiece with brass and cast iron fittings.[24] This room leads to the Dining Room which occupies the west side of the building. It has been described as "the most sumptuous room in the building".[24] Around the room are Corinthian pilasters. The plaster ceiling has moulded compartments and under these is a frieze decorated with scrolls, urns and crouching dogs. The roundels between the capitals of the pilasters contain paintings of pairs of cupids.[24][26]

The next room on the circuit is a small room which leads into the Large Ballroom. This occupies the whole of Wyatt's north extension and measures 89 feet (27 m) by 42 feet (13 m); the ceiling is 40 feet (12 m) high. Around the room are Corinthian pilasters and on each of the shorter walls is a massive mirror. In the south wall is a niche for musicians, over which is a coffered semi-dome; on each side of this is a white marble chimneypiece.[27][28] Hanging from the ceiling are "three of the finest Georgian chandeliers in Europe";[28] each is 28 feet (9 m) high, contains 20,000 pieces of cut glass crystal, and weighs over one ton. They were made in Staffordshire in 1820. The floor is a maple sprung dance floor.[28] Most of the east side of the hall is occupied by the Small Ballroom, also known as the East Reception Room or Music Room. This room is surrounded by pilasters and at each end is a shallow apse; the apse in the north wall has two niches for musicians. Suspended from the ceiling are three 19th century chandeliers.[2][29] Completing the circuit is the East Reception Room, similar in style to the West Reception Room.[2] The rooms contain a number of portraits; one of these is of James Maury, America's first consul.[30]

Current use and surroundings edit

Liverpool City Council meets every seven weeks in the Council Chambers to conduct the business of the city.[21] The town hall is open to the general public each month when conducted tours take place.[31] The hall is licensed for weddings and, in addition to providing a venue for the ceremony, catering facilities can be supplied for a reception or a meal.[32] Catering is also available for other events and functions.[33] Council officers and their departments are based in the nearby Cunard Building.[34]

Immediately to the north of the town hall is a paved square known as Exchange Flags; this is surrounded on all sides by modern office buildings. In the square is the Nelson Monument, celebrating the achievements of Horatio Nelson. It is a Grade II* listed building and is the earliest surviving public monument in the city.[35]

Gallery edit

-

Liverpool Town Hall in 1907, looking down Water Street, painting by J. Hamilton Hay

-

Dome with statue of Britannia

-

Liverpool Exchange and its members, 1847

-

Entrance Hall

-

These encaustic tiles are on the ground floor of Liverpool Town Hall

-

Encaustic tiles in the Entrance Hall

-

Hall of Remembrance

-

Hall of Remembrance

-

Gents toilets

-

Statue of George Canning 1832 by Francis Leggatt Chantrey

-

Central Reception Room

-

Niche in Central Reception Room

-

Small Ballroom

-

Large Ballroom

-

Orchestra balcony, Large Ballroom

-

Dining Room

-

Urn in the Dining Room

See also edit

References edit

Citations

- ^ a b c d Historic England, "Town Hall, Liverpool (1360219)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 20 August 2013

- ^ a b c Pollard & Pevsner 2006, p. 291.

- ^ a b c Liverpool Town Hall and its history, City of Liverpool, archived from the original on 10 May 2012, retrieved 23 October 2009

- ^ a b c Pollard & Pevsner 2006, p. 286.

- ^ a b c d Pollard & Pevsner 2006, p. 287.

- ^ Fairclough, Oliver (Winter 1976). "Joseph Finney of Liverpool". Antiquarian Horology. 10 (1): 35.

- ^ Hunter, B. (2002), Forgotten Hero - The Life and Times of Edward Rushton, Living History Library. ISBN 0-9542077-0-X

- ^ "Surrender of the Shenandoah", 26 June 2015, archived from the original on 26 June 2015, retrieved 1 January 2017

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b c Pollard & Pevsner 2006, p. 288.

- ^ Hartnup, John (1858). "On Controlling the Movements of Ordinary Clocks by Galvanic Currents". Report of the Twenty-seventh Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science; held at Dublin in August and September 1857. 2: 13.

- ^ "Horology". Chambers's Encyclopaedia, volume V. London: W. and R. Chambers. 1880. p. 423.

- ^ "On Controlling Clocks by Electricity". Report of the Council to the Forty-first Annual General Meeting of the Society. XXI (4): 112. 8 February 1861.

- ^ a b c d e Pollard & Pevsner 2006, p. 289.

- ^ a b Hall of Remembrance, City of Liverpool, retrieved 24 October 2009

- ^ a b Town Hall, Liverpool City Council, archived from the original on 26 October 2009, retrieved 24 November 2009

- ^ Graves, Steve (29 May 2014), "Liverpool Town Hall begins to return to its former glory", Liverpool Echo, retrieved 1 January 2017

- ^ Pollard & Pevsner 2006, pp. 286–289.

- ^ a b "Town Hall", Spike say Cheese, retrieved 10 April 2020

- ^ Pevsner' Pollard (2006), p289

- ^ Entrance Hall, City of Liverpool, archived from the original on 29 August 2010, retrieved 24 October 2009

- ^ a b Council Chamber, City of Liverpool, archived from the original on 29 August 2010, retrieved 24 October 2009

- ^ Pollard & Pevsner 2006, pp. 289–290.

- ^ The Staircase, City of Liverpool, archived from the original on 3 August 2012, retrieved 24 October 2009

- ^ a b c d Pollard & Pevsner 2006, p. 290.

- ^ Reception Rooms, City of Liverpool, archived from the original on 26 June 2007, retrieved 26 October 2009

- ^ Dining Room, City of Liverpool, archived from the original on 23 August 2008, retrieved 1 November 2009

- ^ Pollard & Pevsner 2006, pp. 290–291.

- ^ a b c Large Ballroom, City of Liverpool, archived from the original on 23 December 2012, retrieved 1 November 2009

- ^ Small Ballroom, City of Liverpool, archived from the original on 26 June 2007, retrieved 1 November 2009

- ^ Cultural Connections: Liverpool, Embassy of the United States, archived from the original on 21 August 2008, retrieved 2 November 2009

- ^ Open days and tours, City of Liverpool, archived from the original on 13 February 2010, retrieved 1 November 2009

- ^ Weddings, City of Liverpool, retrieved 1 November 2009

- ^ Functions, City of Liverpool, retrieved 1 November 2009

- ^ "Licensing: Responsible authorities". Liverpool City Council. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ Historic England, "Nelson Monument, Exchange Flags, Liverpool (1068235)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 20 August 2013

Sources

- Pollard, Richard; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2006), Lancashire: Liverpool and the South-West, The Buildings of England, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-10910-5

External links edit

Media related to Liverpool Town Hall at Wikimedia Commons