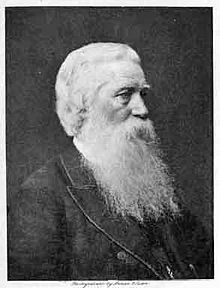

John Gibson Paton (24 May 1824 – 28 January 1907), born in Scotland , was a Protestant missionary to the New Hebrides Islands of the South Pacific.[1] He brought to the natives of the New Hebrides education and Christianity. He developed small industries for them, such as hat making. He advocated strongly against a form of slavery, which was called "Blackbirding", that involved kidnapping the natives and forcing them to work in New Zealand and elsewhere.

John Gibson Paton | |

|---|---|

Missionary to the New Hebrides | |

| Born | 24 May 1824 Braehead, Kirkmahoe, Dumfriesshire, Scotland |

| Died | 28 January 1907 (aged 82) Cross St, Canterbury, Victoria, Australia |

Though his life and work in the New Hebrides was difficult and often dangerous, Paton preached, raised a family, and worked to raise support in Scotland for missionary work. He also campaigned hard to persuade Britain to annex the New Hebrides. He was a man of robust character and personality. Paton was also an author and able to tell his story in print. He is held up as an example and an inspiration for missionary work.[2][3][4]

Early life edit

Paton was born on 24 May 1824, in a farm cottage at Braehead, Kirkmahoe, Dumfriesshire, Scotland. He was the eldest of the 11 children of James and Janet Paton.[5]

Paton was a stocking manufacturer and later a colporteur. James and his wife Janet and their three eldest children, moved c.1828/29 from Braehead to Torthorwald in the same county. There, in a humble thatched cottage of three rooms, his parents reared five sons and six daughters.

John, from the age of 12, started learning the trade of his stocking manufacturing father and, for fourteen hours a day, he manipulated one of the six "stocking frames" in his father's workshop.

However, he still studied during the two hours allotted each day for the eating of his meals.

During these years, Paton was greatly influenced by the devoutness of his father who would go three times a day to his "prayer closet" and who conducted family prayers twice a day.

During his youth Paton felt called by God to serve overseas as a missionary. Eventually he moved to Glasgow (Forty miles on foot to Kilmarnock then by train to Glasgow) where he undertook theological and medical studies.[6] For some years he also worked at distributing tracts, teaching at school, and labouring as a city missionary in a degraded section of Glasgow.[7]

Paton was ordained by the Reformed Presbyterian Church on 23 March 1858.[8] On 2 April, in Coldstream, Berwickshire, Scotland John G. Paton married Mary Ann Robson and 14 days later, on 16 April, accompanied by Mr. Joseph Copeland, they both sailed from Scotland to the South Pacific.[9][10]

The Parting edit

The following excerpt, written by John G. Paton late in his life, is from Missionary Patriarch: The True Story of John G. Paton and provides an example of the relationship between Paton and his father.

My dear father walked with me the first six miles of the way. His counsel and tears and heavenly conversation on that parting journey are fresh in my heart as if it had been but yesterday; and tears are on my cheeks as freely now as then, whenever memory steals me away to the scene. His tears fell fast when our eyes met each other in looks for which all speech was vain! He grasped my hand firmly for a minute in silence, and then solemnly said: "God bless you, my son! Your father's God prosper you, and keep you from all evil!" Unable to say more, his lips kept moving in silent prayer; in tears we embraced, and parted. I ran off as fast as I could; and, when about to turn a corner in the road where he would lose sight of me, I looked back and saw him still standing with head uncovered where I had left him gazing after me. Waving my hat in adieu, I was round the corner and out of sight in an instant. But my heart was too full and sore to carry me further, so I darted into the side of the road and wept for a time. Rising up cautiously, I climbed the dyke to see if he yet stood where I had left him; and just at that moment I caught a glimpse of him climbing the dyke and looking out for me! He did not see me, and after he had gazed eagerly in my direction for a while he got down, set his face towards home, and began to return, his head still uncovered, and his heart, I felt sure, still rising in prayers for me. I watched through blinding tears, till his form faded from my gaze; and then, hastening on my way, vowed deeply and oft, by the help of God, to live and act so as never to grieve or dishonour such a father and mother as He had given me. The appearance of my father when we parted has often through life risen vividly before my mind, and does so now as if it had been but an hour ago. In my earlier years particularly, when exposed to many temptations, his parting form rose before me as that of a guardian Angel.[11] It is no pharisaism, but deep gratitude, which makes me here testify that the memory of that scene not only helped to keep me pure from the prevailing sins, but also stimulated me in all my studies, that I might not fall short of his hopes, and in all my Christian duties, that I might faithfully follow his shining example.[12][page needed]

Early years in New Hebrides edit

John and Mary Paton landed on the island of Tanna, in the southern part of the New Hebrides, on 5 November 1858 and built a small house at Port Resolution.[13] When they arrived, the Canadian missionary John Geddie (1815–72) had already been laboring in the New Hebrides since 1846, where he served primarily on the island of Aneityum.[14]

In those days the natives of Tanna were cannibals. The missionary couple were surrounded by "painted savages who were enveloped in the superstitions and cruelties of heathenism at its worst. The men and children went about in a state of nudity while the women wore abbreviated grass or leaf aprons."[citation needed]

Three months after their arrival, a son, Peter Robert Robson, was born on 12 February 1859. But just 19 days later, Mary died from tropical fever soon to be followed to the grave by the newly born Peter at 36 days of age.

Paton buried his wife and child together, close to their house in Resolution Bay. He spent nights sleeping on their grave to protect them from the local cannibals. The gravesite is still accessible to this day with a plaque marking the spot, erected in 1996.[citation needed]

Paton continued unfailingly with his missionary work in spite of constant animosity from the natives and many attempts on his life.[15] During one attack, a ship arrived just in time to rescue him and take him and missionaries from another part of the island, Mr. and Mrs. Mathieson, to safety at Aneityum.[16][17]

Visit to Australia and Scotland and second marriage edit

From Aneityum, Paton went first to Australia, then to Scotland, to arouse greater interest in the work of the New Hebrides, to recruit new missionaries, and especially to raise a large sum of money for the building and upkeep of a sailing ship to assist the missionaries in the work of evangelizing the Islands.[18][19] Later he raised a much larger sum with which to build a mission steamship.

During this time in Scotland, on 17 June 1864, in Edinburgh, Scotland, Paton married Margaret (Maggie) Whitecross, a descendant of the so-called "Whitecross Knights". She was a sister of Helen Whitecross (c. 1832 – 22 October 1902) who married Rev. James Lyall (9 April 1827 – 10 September 1905), a pioneering Presbyterian minister of Adelaide, South Australia.[20] Their son Robert Robson Paton was born at Victoria Square, Adelaide, on 24 March 1865. Later as Rev. Robert Paton, he died in Blackburn, Victoria on 11 April 1911. He was married to Bessie and had five children.[21]

Return to the New Hebrides edit

Arriving back in the New Hebrides in August 1866, John and his new wife Maggie established a new Mission station on Aniwa Island, the nearest island to Tanna.[22] There they lived in a small native hut while they built a house for themselves and two houses for orphan children. Later, a church, a printing house, and other buildings were erected.

In Aniwa they found the natives to be very similar to those on Tanna – "The same superstitions, the same cannibalistic cruelties and depravities, the same barbaric mentality, the same lack of altruistic or humanitarian impulses were in evidence."

Nevertheless, they continued in their missionary work and it was there in Aniwa that 6 of their 10 children were born, 4 of whom died in early childhood or in infancy. Their fourth son, Frank Hume Lyall Paton, who followed them as a missionary in the New Hebrides, was one of those born on Aniwa Island.

John learned the language and reduced it to writing. Maggie taught a class of about fifty women and girls who became experts at sewing, singing and plaiting hats, and reading. They trained the teachers, translated and printed and expounded the Scriptures, ministered to the sick and dying, dispensed medicines every day, taught them the use of tools, held worship services every Lord's Day and sent native teachers to all the villages to preach the gospel.

Enduring many years of deprivation, danger from natives and disease, they continued with their work and after many years of patient ministry, the entire island of Aniwa professed Christianity. In 1899 Paton saw his Aniwa New Testament printed and the establishment of missionaries on twenty-five of the thirty islands of the New Hebrides.[23][page needed]

Final years edit

In 1889, his brother Reverend James Paton published his biography.[24]

Maggie Whitecross Paton died at the age of 64 on 16 May 1905[25] at "Kennet" - believed to be the family home at 74 Princess Street, Kew, Victoria, Australia.

Paton outlived his wife by nearly two years, dying at the age of 82 on 28 January 1907[25] at Cross St, Canterbury, Victoria, Australia.

They are both buried at Boroondara[25] at the intersection of High Street and Park Hill Road, Kew, Victoria.

The student group at the Presbyterian Theological College in Victoria is named in his honour.

See also edit

- John Williams (missionary) — Early 19th century missionary in the South Pacific

- William Taylor (missionary) — 19th century missionary in central Africa

- Robert Moffat (missionary) — 19th century missionary in South Africa

Bibliography edit

- The Varieties of Religious Experience. In this book the psychiatrist and philosopher William James mentions Paton with a comment on Paton's character, and a lengthy quotation from Paton's autobiography.[26]

- Letters and Sketches from the New Hebrides. Written by Margaret Whitecross Paton.[27]

- John G. Paton's life has been recorded in a series of books edited by his brother James Paton and by his son Frank H. L. Paton together with A. K. Langridge.

- Paton, John (1889). John G. Paton, Missionary to the New Hebrides : an autobiography. Vol. First Part. New York: Carter.

- Edited by his brother Rev. Dr. James Paton

- ——— (1889). John G. Paton, Missionary to the New Hebrides : an autobiography. Vol. Second Part. New York: Carter.

- Edited by his brother Rev. Dr. James Paton

- ——— (1892). The story of John G. Paton: told for young folks, or, Thirty years among South Sea cannibals. New York: Carter.

- ——— (29 January 1907). John G. Paton – Missionary to the New Hebrides – Later Years & Farewell. Melbourne.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

- ———, Langridge, A. K; Paton, F. H. L (eds.), Later Years and Farewell, C. D. Michael.

- Paton, Maggie Whitecross (1895). Letters and sketches from the New Hebrides. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 382.

- Unseth, Benjamin, ed. (1996). John Paton. Minneapolis: Bethany House. p. 160.

- Missionary Patriarch: The True Story of John G. Paton. Evangelist for Jesus Christ Among the South Sea Cannibals, San Antonio, TX: Vision Forum, 2006.

References edit

- ^ Boston University website, Paton, John Gibson (1824-1907)

- ^ Paton, James, The Story of John G. Paton; Or Thirty Years Among South Sea Cannibals, Project Gutenberg.

- ^ "John Gibson Paton", Missions (biography), Wholesome Words, 2015, archived from the original on 4 February 2007, retrieved 23 February 2007.

- ^ Lal, Brij V; Fortune, Kate, eds. (2000), The Pacific Islands: An Encyclopedia, vol. 1, University of Hawaii Press, p. 193, ISBN 978-0-82482265-1.

- ^ Thurn, Everard im (1912). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography (2nd supplement). Vol. 3. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ^ Couper, W. J. (1925). The Reformed Presbyterian Church in Scotland, its congregations, ministers and students. Scottish Church History Society. pp. 136, et passim.

- ^ Mennell, Philip (1892). . The Dictionary of Australasian Biography. London: Hutchinson & Co – via Wikisource.

- ^ Robb, James E. (1975). Cameronian Fasti: Ministers and Missionaries of the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland, 1680-1929. Edinburgh: Reformed Heritage. p. 26.

- ^ Byrum, Bessie L (23 June 2005), John G. Paton: Hero of the South Seas, Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 978-1-41799313-0.

- ^ Paton, John G (2009) [1889], Missionary to the New Hebrides: An Autobiography, Christian Focus, pp. 7–49, ISBN 978-1-84550-453-3.

- ^ Paton, John G (1 October 1965) [1889], John G. Paton: THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF THE PIONEER MISSIONARY TO THE NEW HEBRIDES (VANUATU), Banner of Truth, pp. 24–25, ISBN 9781848712768.

- ^ Paton, John Gibson (2001), Missionary Patriarch: The True Story of John G. Paton, Vision Forum, pp. 24–25, ISBN 978-1-92924137-8.

- ^ Hutchison, Matthew (1893). The Reformed Presbyterian Church in Scotland; its origin and history 1680-1876. Paisley: J. and R. Parlane. pp. 320-322.

- ^ John Geddie, Dictionary of Scottish Church History & Theology, Nigel M. de S. Cameron, Editor. Downers Grove: Intervarsity Press, 1993, 353).

- ^ Paton, John G (2009) [1889], Missionary to the New Hebrides: An Autobiography, Christian Focus, pp. 126–167, ISBN 978-1-84550-453-3.

- ^ Paton, John Gibson. The Story of Dr. John G. Paton's Thirty Years with South Sea Cannibals. George H. Doran Company. (1923)

- ^ Paton, John G (2009) [1889], Missionary to the New Hebrides: An Autobiography, Christian Focus, pp. 168–171, ISBN 978-1-84550-453-3.

- ^ Hutchison, Matthew (1893). The Reformed Presbyterian Church in Scotland; its origin and history 1680-1876. Paisley: J. and R. Parlane. pp. 323-359.

- ^ Paton, John G (2009) [1889], Missionary to the New Hebrides: An Autobiography, Christian Focus, pp. 176–183, ISBN 978-1-84550-453-3.

- ^ Paton, John G (2009) [1889], Missionary to the New Hebrides: An Autobiography, Christian Focus, pp. 214–216, ISBN 978-1-84550-453-3.

- ^ "News". Bairnsdale Advertiser and Tambo and Omeo Chronicle. No. 4661. Victoria, Australia. 13 April 1911. p. 2. Retrieved 4 January 2022 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ Hutchison, Matthew (1893). The Reformed Presbyterian Church in Scotland; its origin and history 1680-1876. Paisley: J. and R. Parlane. pp. 360-365.

- ^ Paton, Margaret Whitecross (1895), Letters and Sketches from the New Hebrides, Stoughton.

- ^ Gutenberg website, The Story of John G. Paton, by James Paton (online copy)

- ^ a b c Hilliard, David (23 September 2004). "Paton, John Gibson (1824–1907), missionary". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 1 (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/35411. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ James, William (2000), The Varieties of Religious Experience, Random House, note 14, ISBN 978-0-67964158-2.

- ^ Paton, Margaret Whitecross (1895), Letters and Sketches from the New Hebrides, Stoughton.

External links edit

- Works by John Gibson Paton at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about John Gibson Paton at Internet Archive

- "You Will Be Eaten by Cannibals!" Lessons from the Life of John G. Paton (biography), Desiring God.

- Reformation History website, John G Paton (Worms, Cannibals and the History of Scottish RP Mssions)

- Beeke, Joel, "Preface", The Letters and Sketches of Maggie Paton from the New Hebrides.

- Paton, John Gibson (1891), "Unter Kannibalen auf den Neuen Hebriden", in Paul, Johannes [in German] (ed.), Von Grönland bis Lambarene. Reisebeschreibungen christlicher Missionare aus drei Jahrhunderten (in German), Evangelische Verlagsanstalt, Berlin 1951, 1952, 1953 (po. 83–96) and Kreuz-Verlag, Stuttgart 1958 (pp. 79–92). Formerly published in: ——— (1891), Missionar auf den Neuen Hebriden. Eine Selbstbiographie, Leipzig: H. G. Wallmann.