Graciliceratops (meaning "slender horn") is a genus of neoceratopsian dinosaurs that lived in Asia during the Late Cretaceous period.

| Graciliceratops Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

~ | |

|---|---|

| |

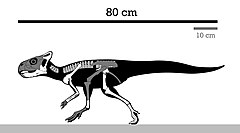

| Skeletal diagram featuring the known elements from the holotype | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Ceratopsia |

| Infraorder: | †Neoceratopsia |

| Genus: | †Graciliceratops Sereno, 2000 |

| Type species | |

| †Graciliceratops mongoliensis Sereno, 2000

| |

Discovery and naming edit

The holotype, ZPAL MgD-I/156, was discovered at the Bayan Shireh Formation in Mongolia, coming from the Sheeregeen Gashoon locality near Sainshand. The discoveries were made during field exploration by the Polish-Mongolian Palaeontological Expedition, in 1971. Four years later, in 1975, the specimen was described by Teresa Maryańska and Halszka Osmólska and referred to the genus Microceratops.[1] However, Paul Sereno noted that the referral for this specimen was injustified and overall, the genus lacked diagnosis, therefore, Microceratops (now named Microceratus[2]) was considered a nomen dubium. The referred specimen was redescribed by him, creating a new genus and species: Graciliceratops mongoliensis.[3]

The holotype is fragmentary, consisting of a very fragmented skull with mandibles; vertebrae, four cervicals, twelve dorsals and seven sacrals; right scapula; proximal end of left scapula; left coracoid; right humerus, radius and fragmentary ulna; proximal and distal end of left humerus; proximal fragments of both pubis; fragments of both ilium and fragment of right ischium; right femur, tibia and nearly complete pes; distal part of left tibia, fragmentary left pes; tarsals and isolated ribs.[1] The generic name, Graciliceratops, is derived from the Latin gracilis (meaning slender) and the Greek κέρας (kéras, meaning horn) in reference to its fragile build. Lastly, the specific name, mongolienses, is to emphasize the place of its discovery: Mongolia.[3]

Description edit

Although very damaged, the skull measures approximately 20 cm (200 mm), the arches and centra of the sacral vertebrae are not fused, which indicates that this specimen was not fully grown when it died, probably a juvenile individual.[1] Its size is estimated at 60 cm (2.0 ft) long with a weight between 2.27 to 9.1 kg (5.0 to 20.1 lb).[4] However, due to the immature nature of the specimen, the adult size is estimated around 2 m (6.6 ft), or similar to Protoceratops. The frill has large fenestrae bounded by very slender struts. This structure is very similar to that of the later Protoceratops. Graciliceratops is recognised by the fragile frill and characteristic tibial-femoral ratio (1.2:1); the frill is also briefly elongated with well developed squamosal processes.[3] Seven sacral vertebrae were identified and not fused. The scapula is very gracile in constitution but thicker at the glenoid, with a relatively large coracoid; the humerus is also very slender. The femur measures 9.5 cm (95 mm), it is lightly curved and has a large head; the fourth trochanter is fragile and place above the midlength of the femoral end. Being larger than the femur, the tibia measures 11 cm (110 mm) and its proximal articulation is more developed than distally. The right pes is virtually complete, only lacking the distal end of the IV metatarsal. The pedal unguals are dorsoventrally flattened and somewhat sharply-developed.[1]

Classification edit

During the description of Aquilops in 2014, an extensive Ceratopsia phylogenetic analysis was conducted. Graciliceratops was found to be a basal neoceratopsian. Below are the results obtained for the Neoceratopsia:[5]

Paleoecology edit

Graciliceratops was unearthed from the Sheeregeen Gashoon beds, which are part of the Upper Bayan Shireh. The presence of caliche, fluvial and lacustrine sediments, indicate a semiarid climate with rivers and large lakes around the zone.[6][7] Fossilized fruits have also been recovered from the upper and lower parts of the formation, suggesting the existence of Angiosperm plants.[8] Magnetostratigraphic and calcite U–Pb analyses indicate that the formation lies within the Cretaceous Long Normal, which was deposited until the end of the Santonian around 95.9 ± 6.0 million to 89.6 ± 4.0 million years ago.[9][10]

It lived alongside other dinosaurs from the upper part, most notably the large dromaeosaurid Achillobator, the tyrannosauroid Alectrosaurus, therizinosaurs Erlikosaurus, ‘’Enigmosaurus’’, and Segnosaurus, the pachycephalosaur Amtocephale, the ornithomimid ‘’Garudimimus’’, the ankylosaurs Talarurus, ‘’Amtosaurus’’, ‘’Maleevus’’, and Tsagantegia, the large sauropod Erketu and the basal hadrosauroid Gobihadros.[6][11][8] Additional paleofauna has been recovered, expanding the aquatic biodiversity: Paralligator,[12] Lindholmemys[13] and the shark Hybodus.[14] The discoveries of azhdarchids pterosaurs have been reported from at least two locations, compromising mainly cervical vertebrae.[15]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c d Maryańska, T.; Osmólska, H. (1975). "Protoceratopsidae (Dinosauria) of Asia" (PDF). Palaeontologia Polonica. 33: 134–143.

- ^ Mateus, O. (2008). "Two ornithischian dinosaurs renamed: Microceratops Bohlin 1953 and Diceratops Lull 1905". Journal of Paleontology. 82 (2): 423. doi:10.1666/07-069.1. S2CID 86021954.

- ^ a b c Sereno, P. C. (2000). "The fossil record, systematics and evolution of pachycephalosaurs and ceratopsians from Asia". The Age of Dinosaurs in Russia and Mongolia (PDF). Cambridge University Press. pp. 489–492.

- ^ Holtz, T. R.; Rey, L. V. (2007). Dinosaurs: The Most Complete, Up-to-Date Encyclopedia for Dinosaur Lovers of All Ages. Random House. Genus List for Holtz 2012 Weight Information

- ^ Farke, A. A.; Maxwell, W. D.; Cifelli, R. L.; Wedel, M. J. (2014). "A Ceratopsian Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Western North America, and the Biogeography of Neoceratopsia". PLOS ONE. 9 (12): e112055. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9k2055F. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0112055. PMC 4262212. PMID 25494182.

- ^ a b Jerzykiewicz, T.; Russell, D. A. (1991). "Late Mesozoic stratigraphy and vertebrates of the Gobi Basin". Cretaceous Research. 12 (4): 345–377. doi:10.1016/0195-6671(91)90015-5. ISSN 0195-6671.

- ^ Sochava, A. V. (1975). "Stratigraphy and lithology of the Upper Cretaceous sediments in southern Mongolia. In Stratigraphy of Mesozoic sediments of Mongolia". Transactions of Joint Soviet–Mongolian Scientific Research and Geological Expedition. 13: 113–182.

- ^ a b Ksepka, D. T.; Norell, M. A. (2006). "Erketu ellisoni, a long-necked sauropod from Bor Guvé (Dornogov Aimag, Mongolia)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3508): 1–16. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2006)3508[1:EEALSF]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Hicks, J.F.; Brinkman, D.L.; Nichols, D.J.; Watabe, M. (1999). "Paleomagnetic and palynologic analyses of Albian to Santonian strata at Bayn Shireh, Burkhant, and Khuren Dukh, eastern Gobi Desert, Mongolia". Cretaceous Research. 20 (6): 829–850. doi:10.1006/cres.1999.0188.

- ^ Kurumada, Y.; Aoki, S.; Aoki, K.; Kato, D.; Saneyoshi, M.; Tsogtbaatar, K.; Windley, B. F.; Ishigaki, S. (2020). "Calcite U–Pb age of the Cretaceous vertebrate-bearing Bayn Shire Formation in the Eastern Gobi Desert of Mongolia: usefulness of caliche for age determination". Terra Nova. 32 (4): 246–252. Bibcode:2020TeNov..32..246K. doi:10.1111/ter.12456.

- ^ Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmolska, H. (2004). "Dinosaur Distribution". The Dinosauria, Second Edition. University of California Press. pp. 596–597.

- ^ Turner, A. H. (2015). "A Review of Shamosuchus and Paralligator (Crocodyliformes, Neosuchia) from the Cretaceous of Asia". PLOS ONE. 10 (2): e0118116. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1018116T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0118116. PMC 4340866. PMID 25714338.

- ^ Sukhanov, V. B.; Danilov, I. G.; Syromyatnikova, E. V. (2008). "The Description and Phylogenetic Position of a New Nanhsiungchelyid Turtle from the Late Cretaceous of Mongolia". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 53 (4): 601–614. doi:10.4202/app.2008.0405.

- ^ Averianov, A.; Sues, H. (2012). "Correlation of Late Cretaceous continental vertebrate assemblages in Middle and Central Asia" (PDF). Journal of Stratigraphy. 36 (2): 462–485. S2CID 54210424. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-03-07.

- ^ Watabe, M.; Suzuki, D.; Tsogtbaatar, K. (2009). "The first discovery of pterosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous of Mongolia" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 54 (2): 231–242. doi:10.4202/app.2006.0068.