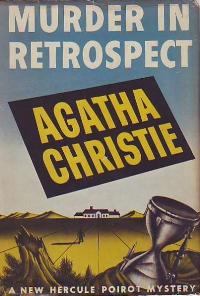

Five Little Pigs is a work of detective fiction by British writer Agatha Christie, first published in the US by Dodd, Mead and Company in May 1942 under the title Murder in Retrospect[1] and in the UK by the Collins Crime Club in January 1943 (although some sources state that publication was in November 1942).[2] The UK first edition carries a copyright date of 1942 and retailed at eight shillings[2] while the US edition was priced at $2.00.[1]

Dust-jacket illustration of the US (true first) edition with alternative title. See Publication history (below) for UK first edition jacket image with original title. | |

| Author | Agatha Christie |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Not known |

| Country | United Kingdom United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | Hercule Poirot |

| Genre | Crime novel |

| Publisher | Dodd, Mead and Company |

Publication date | May 1942 |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 234 (first edition, hardback) |

| ISBN | 0-00-616372-6 |

| Preceded by | Evil Under the Sun |

| Followed by | The Hollow |

In the book, detective Hercule Poirot investigates five people about a murder committed sixteen years earlier. Caroline Crale died in prison after being convicted of murdering her husband, Amyas Crale, by poisoning him. In her final letter from prison, she claims to be innocent of the murder. Her daughter Carla Lemarchant asks Poirot to investigate this cold case, based on the memories of the people closest to the couple.

Plot summary edit

Sixteen years after Caroline Crale was convicted for the murder of her husband Amyas, her twenty-one-year-old daughter Carla Lemarchant asks Hercule Poirot to reinvestigate the case, after she was given a letter from her late mother claiming she was innocent, which Carla believes to be true. Poirot agrees to her request and establishes that on the day of the murder at the Crales' home there were five other people present, whom Poirot dubs "the five little pigs" – stockbroker Philip Blake, amateur chemist Meredith Blake (Philip's brother), Caroline's young half-sister Angela Warren, Angela's governess Cecilia Williams and Amyas's painting model Elsa Greer. The police found that Amyas was poisoned by coniine, found in a glass he had drunk from. Caroline confessed to stealing the poison from Meredith's lab, intending to use it to commit suicide. She had brought a cold bottle of beer to Amyas and the police think she had poisoned it, because Amyas was having an affair with his model Elsa.

Poirot interviews the five other suspects and notes that none has an obvious motive. Caroline's half-sister Angela is the only one who believes Caroline was innocent. He assembles them, along with Carla and her fiancé and reveals that Caroline was innocent but chose not to defend herself because she believed Angela had committed the murder. Although Angela had handled the beer bottle she had added nothing to it before her sister took it to Amyas. Caroline later assumed that her sister had added something to the beer as a prank, causing Amyas's death. When they were much younger, Caroline had thrown a paperweight at Angela injuring her face and saw this as a way to atone for that incident.

Poirot gathers the five suspects together and states that the murderer was Elsa Greer. She had taken Amyas' promise to marry her seriously, unaware that he only wanted her to continue as his model until the painting was done. She overheard Amyas reassure his wife that he was not leaving her, felt betrayed and wanted revenge. She had seen Caroline take the poison from Meredith's lab, so she took it from Caroline's room and put it in a glass of warm beer that she gave Amyas. When Caroline later brought him a cold bottle of beer, he commented that "everything tastes foul today", and drank the cold beer from the bottle. This indicated to Poirot that the poison had been in the glass Elsa had given him. Poirot's explanation solves the case to the satisfaction of Carla and her fiancé. Although the chances of getting a pardon for Caroline or a conviction of Elsa are slim with circumstantial evidence, Poirot plans to present his findings to the police. As Elsa leaves, she claims that she is the true victim of the case because she is the one who must live with the guilt.

Characters edit

- Hercule Poirot: the Belgian Detective.

- Carla Lemarchant: the daughter of Caroline and Amyas Crale; also born Caroline Crale, she was aged 5 when her father was murdered at their home, Alderbury.

- John Rattery: fiancé of Carla.

- Amyas Crale: painter by profession and a man who liked his paintings and mistresses, but loved his wife most. He was murdered 16 years before the story opens.

- Caroline Crale: wife of Amyas, half-sister to the younger Angela Warren. She was found guilty of the murder of her husband and died in prison within a year.

- Sir Montague Depleach: Counsel for the Defence in the original trial.

- Quentin Fogg, KC: Junior for the Prosecution in the original trial.

- George Mayhew: son of Caroline's solicitor in the original trial.

- Edmunds: Managing clerk in Mayhew's firm.

- Caleb Jonathan: Family solicitor for the Crales.

- Superintendent Hale: Investigating officer in the original case.

The five people Poirot questions, who he dubs "the five little pigs" after the nursery rhyme This Little Piggy, are:

- Philip Blake: a stockbroker ("This little piggy went to market"). He expressed disdain for Caroline, but was actually attracted to her.

- Meredith Blake: Philip's elder brother, a reclusive one-time amateur herbalist who owns the adjacent property Handcross Manor ("This little piggy stayed at home"). He had at one point hoped to marry Caroline, but after the murder he proposed to Elsa and was rejected.

- Elsa Greer (Lady Dittisham): a spoiled society lady, then twenty-year-old mistress to Amyas Crale ("This little piggy had roast beef").

- Cecilia Williams: the devoted governess ("This little piggy had none").

- Angela Warren: half-sister of Caroline Crale, a disfigured archaeologist ("This little piggy cried 'wee wee wee' all the way home"). Caroline disfigured her as an infant in a fit of jealousy, an incident she was deeply ashamed of as an adult and caused her to be overly protective of Angela. She was a teenager at the time of the murder.

Literary significance and reception edit

Author and critic Maurice Willson Disher's review in The Times Literary Supplement of 16 January 1943 concluded, "No crime enthusiast will object that the story of how the painter died has to be told many times, for this, even if it creates an interest which is more problem than plot, demonstrates the author's uncanny skill. The answer to the riddle is brilliant."[3]

Maurice Richardson reviewed the novel in the 10 January 1943 issue of The Observer, writing: "Despite only five suspects, Mrs Christie, as usual, puts a ring through the reader's nose and leads him to one of her smashing last-minute showdowns. This is well up to the standard of her middle Poirot period. No more need be said."[4]

J D Beresford in The Guardian's 20 January 1943 review, wrote: "...Christie never fails us, and her Five Little Pigs presents a very pretty problem for the ingenious reader". He concluded that the clue as to who had committed the crime was "completely satisfying".[5]

Robert Barnard has strong praise for this novel and its plot. He remarked that it was "The-murder-in-the-past plot on its first and best appearance – accept no later substitutes. Presentation more intricate than usual, characterization more subtle."[6] His judgment was that "All in all, it is a beautifully tailored book, rich and satisfying. The present writer would be willing to chance his arm and say that this is the best Christie of all."[6]

Charles Osborne praised this novel, saying that "The solution of the mystery in Five Little Pigs is not only immediately convincing but satisfying as well, and even moving in its inevitability and its bleakness."[7]

References and allusions edit

This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2017) |

The novel's title is from the nursery rhyme This Little Piggy, which is used by Poirot to organise his thoughts regarding the investigation. Each of the five little pigs mentioned in the nursery rhyme is used as a title for a chapter in the book, corresponding to the five suspects.[8] Agatha Christie used this style of title in other novels, including One, Two, Buckle My Shoe, Hickory Dickory Dock, A Pocket Full of Rye, and Crooked House.[9]

Hercule Poirot mentions the celebrated case of Hawley Harvey Crippen as an example of a crime reinterpreted to satisfy the public enthusiasm for psychology.[10]

Romeo and Juliet is a theme among characters recalling the trial, starting with solicitor Caleb Jonathan reading Juliet's lines from the balcony scene: "If that thy bent of love...". Jonathan compares Juliet to the character of Elsa Greer, for their passion, recklessness, and lack of concern about other people.[11]

Coniine (in the story, specifically coniine hydrobromide, derived from poison hemlock) was indeed the poison with which Socrates took his own life, as described by Phaedo, and has indeed been used to treat whooping cough and asthma.[12] The "poisons act" referred to is the Pharmacy and Poisons Act 1933, now superseded by the Poisons Act 1972.

The painting that is hung upon the wall of Cecilia Williams' room, described as a "blind girl sitting on an orange," is by George Frederic Watts and is called "Hope." In it, a blind girl is featured with a harp which, though it has only one string left, she does not give up playing. The description is by Oswald Bastable, a character in the third book in the Bastable series by E. Nesbit, titled The New Treasure Seekers.[13] The other identifiable prints are Dante and Beatrice, and Primavera by Botticelli.

Amyas has two paintings in the Tate. Miss Williams remarks disparagingly that "So is one of Mr Epstein's statues," referring to American-born British sculptor Jacob Epstein.

When Poirot approaches Meredith Blake, he introduces himself as a friend of Lady Mary Lytton-Gore, a character known from Three Act Tragedy. This case is later referred to by Poirot many years later, in Elephants Can Remember, published in 1972.

"Take what you want and pay for it, says God" is referred to as an "old Spanish proverb" by Elsa. The same proverb is cited in Hercule Poirot's Christmas. The proverb is mentioned in South Riding (1936), by Winifred Holtby, and in Windfall's Eye (1929), by Edward Verrall Lucas.

The "interesting tombs in the Fayum" refers to the Fayum Basin south of Cairo, famous for Fayum mummy portraits.

Angela Warren refers to Shakespeare, and quotes John Milton's Comus: "Under the glassy, cool, translucent wave".

In the UK version of the story Five Little Pigs, Poirot refers to the novel The Moon and Sixpence, by W. Somerset Maugham, when he asks Angela Warren if she had recently read it at the time of the murder. Poirot deduces that Angela must have read The Moon and Sixpence from a detail given in Philip Blake's account of the murder, in which he describes an enraged Angela quarrelling with Amyas and expressing the hope that Amyas would die of leprosy.[14] The central character of The Moon and Sixpence, Charles Strickland, is a stockbroker who deserts his wife and children to become an artist and eventually dies of leprosy.[15][note 1]

Adaptations edit

1960 play edit

In 1960, Christie adapted the book into a play, Go Back for Murder, but edited Poirot out of the story. His function in the story is filled by a young lawyer, Justin Fogg, son of the lawyer who led Caroline Crale's defence. During the course of the play, it is revealed that Carla's fiancé is an obnoxious American who is strongly against her revisiting the case, and in the end, she leaves him for Fogg. Go Back for Murder previewed in Edinburgh, Scotland. It later came to London's Duchess Theatre on 23 March 1960, but it lasted for only thirty-seven performances.[19]

Go Back for Murder was included in the 1978 Christie play collection, The Mousetrap and Other Plays.[19]

Television edit

- 2003: Five Little Pigs – Episode 1, Series 9, of Agatha Christie's Poirot, starring David Suchet as Poirot. There were many changes to the story. Caroline was executed, instead of being sentenced to life in prison and then dying a year later. Philip has a romantic infatuation with Amyas, rather than Caroline, the root of his dislike for Caroline. Carla's name was changed to Lucy and she has no fiancé. She does not fear she has hereditary criminal tendencies; she merely wishes to prove her mother innocent. After Poirot exposes Elsa, Lucy threatens her with a pistol; Elsa dares her to shoot, but Poirot persuades her to leave Elsa to face justice.

- The cast of the 2003 version includes Rachael Stirling as Caroline, Julie Cox as Elsa, Toby Stephens as Philip, Aidan Gillen as Amyas, Sophie Winkleman as adult Angela, Talulah Riley as young Angela, Aimee Mullins as Lucy, Marc Warren as Meredith, Patrick Malahide as Sir Montague Depleach, and Gemma Jones as Miss Williams.

- 2011: Cinq petits cochons – Episode 7, Series 1, of Les Petits Meurtres d'Agatha Christie, a French television series. The setting is changed to France, Poirot is omitted, and the case is solved by Émile Lampion (Marius Colucci), a police detective turned private investigator, and his former boss, Chief Inspector Larosière (Antoine Duléry). The plot is once again adapted very loosely. The character of Philip Blake is omitted. Caroline is alive and exonerated at the end. The identification of the "five little pigs" with the suspects is omitted, but the rhyme appears in the Carla character's childhood memories of her father.

Radio edit

Five Little Pigs was adapted for radio and broadcast on BBC Radio 4 in 1994, featuring John Moffatt as Poirot.

Publication history edit

- 1942, Dodd Mead and Company (New York), May 1942, Hardback, 234 pp

- 1943, Collins Crime Club (London), January 1943, Hardback, 192 pp

- 1944, Alfred Scherz Publishers (Berne), Paperback, 239 pp

- 1948, Dell Books, Paperback, 192 pp (Dell number 257 [mapback])

- 1953, Pan Books, Paperback, 189 pp (Pan number 264)

- 1959, Fontana Books (Imprint of HarperCollins), Paperback, 192 pp

- 1982, Ulverscroft Large-print Edition, Hardcover, 334 pp; ISBN 0-7089-0814-4

- 2008, Agatha Christie Facsimile Edition (Facsimile of 1943 UK First Edition), HarperCollins, 1 April 2008, Hardback; ISBN 0-00-727456-4

The novel was first serialized in the US in Collier's Weekly in ten installments from 20 September (Volume 108, Number 12) to 22 November 1941 (Volume 108, Number 21) as Murder in Retrospect with illustrations by Mario Cooper.

Notes edit

- ^ However, in the US version, Murder in Retrospect, Poirot only refers to a book of "a life of the painter Gauguin" without mentioning any title or author, but with the reference to leprosy unchanged.[16] At one time it was thought Gauguin had died of leprosy but this had been debunked as early as 1921.[17][18]

References edit

- ^ a b Marcum, J S (May 2007). "American Tribute to Agatha Christie: The Classic Years: 1940 – 1944". Insight BB. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ a b Peers, Chris; Spurrier, Ralph; Sturgeon, Jamie (March 1999). Collins Crime Club – A checklist of First Editions (Second ed.). Dragonby Press. p. 15.

- ^ Disher, Maurice Wilson (16 January 1943). "Review". The Times Literary Supplement. p. 29.

- ^ Richardson, Maurice (10 January 1943). "Review". The Observer. p. 3.

- ^ Beresford, J D (20 January 1943). "Review". The Guardian. p. 3.

- ^ a b Barnard, Robert (1990). A Talent to Deceive – an appreciation of Agatha Christie (Revised ed.). Fontana Books. pp. 85, 193. ISBN 0-00-637474-3.

- ^ Osborne, Charles (1982). The Life and Crimes of Agatha Christie. London: Collins. p. 130. ISBN 0002164620.

- ^ Cawthorne, Nigel (2014). A brief guide to Agatha Christie. London: Little, Brown Book Group. ISBN 9781472110572. OCLC 878861225.

- ^ Maida, Patricia D; Spornick, Nicholas B. (1982). Murder she wrote : a study of Agatha Christie's detective fiction. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 0879722150. OCLC 9167004.

- ^ "Ghosts of Painters Past: Five Little Pigs | 1942". The Year of Agatha. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Sawabe, Yuko (15 March 2015). "To See or Not To See, That Is the Question: The Elusive Riches of Literary Allusions". Memoirs. 47 (3).

- ^ "coniine". oup.com.

- ^ Tromans, Nicholas (2011). 'Hope' : the life and times of a Victorian icon. Watts Gallery (Compton, Surrey). Compton: Watts Gallery. ISBN 9780956102270. OCLC 747085416.

- ^ Christie, Agatha (1991). Murder on the Orient Express; Cards on the table; Five little pigs; Hercule Poirot's Christmas. Diamond Books. pp. 637, 597. ISBN 0-583-31348-5. reprinting Christie, Agatha (1942). Five Little Pigs. Great Britain: William Collins Sons.

- ^ Maugham, W. Somerset (1919). The Moon and Sixpence. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. pp. 294–300.

- ^ Christie, Agatha (1984). Murder in Retrospect. Berkeley Publishing Corporation. pp. 191, 138. ISBN 0-425-09325-5. reprinting Christie, Agatha (1942). Murder in Retrospect. New York: Dodd, Mead.

- ^ Maurer, Naomi Margolis (1998). The Pursuit of Spiritual Wisdom: The Thought and Art of Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 167. ISBN 0-8386-3749-3.

- ^ Fletcher, John Gould (1921). Paul Gauguin: His Life and Art. New York: Nicholas L. Brown.

- ^ a b Kabatchnik, Amnon (2011). Blood on the stage, 1950-1975 : milestone plays of crime, mystery, and detection. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810877849. OCLC 715421383.

External links edit

- Five Little Pigs at the official Agatha Christie website

- Five Little Pigs (2003) at IMDb