Emil Bessels (2 June 1847 – 30 March 1888) was a German zoologist, entomologist, physician, and Arctic researcher who is best known for his controversial role in the attempted but ill-fated Polaris expedition to the North Pole in 1871. Circumstantial evidence strongly points to Bessels as the most likely suspect in the death of the expedition's commander, American explorer Charles Francis Hall, by arsenic poisoning.

Emil Bessels | |

|---|---|

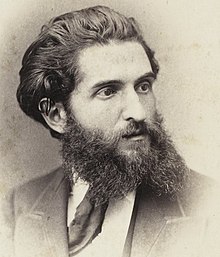

Bessels in 1880 | |

| Born | 2 June 1847 |

| Died | 30 March 1888 (aged 40) |

| Alma mater | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medicine, entomology, zoology |

| Institutions | |

Expeditions | |

Bessels spent much of his scientific career at the Smithsonian Institution.

Career edit

German North Polar expedition edit

In 1869, on suggestion from August Petermann, Bessels joined the German North Polar expedition to the Arctic Sea with the aim of investigating the islands of Spitsbergen and Novaya Zemlya, and surveying the ocean in their vicinity.[1] Because of adverse ice conditions, only the first destination could be reached. During the expedition, hydrographical measurements were performed and the climatological influence of the Gulf Stream on the eastern coast of Spitsbergen was demonstrated.

Franco-Prussian War edit

After his return to his home country in 1870, he joined the Royal Prussian Army in time for the Franco-Prussian War. He was called to the field as military surgeon and rendered service in the hospitals, for which he received a public commendation from Frederick I, Grand Duke of Baden.

Polaris expedition edit

In 1871, Bessels joined the United States North Polar expedition, better known as the Polaris expedition, commanded by eccentric American explorer Charles Francis Hall, who aimed to be the first to reach the North Pole. Bessels signed on as ship's physician and as head of the scientific team.[2]

He and Hall soon came into conflict over control of scientific research on the expedition. When Hall became ill in October 1871, Bessels remained by his bedside for several days, ostensibly to administer medical treatment. However, Hall suspected that Bessels was poisoning him and refused further contact.

After Hall's death several weeks later, Bessels was among those who remained with the Polaris, when most of the crew became separated while trying to salvage supplies. Bessels and his party were eventually forced to abandon the ship, but were rescued and arrived back in the United States in 1873.

Bessels and the other surviving members of the expedition crew were questioned by a naval board of inquiry about the events leading to Hall's death. The official conclusion was that Hall had died of natural causes and had been treated by Bessels to the best of his ability. But in a forensic investigation of Hall's exhumed remains in 1969, lethal amounts of arsenic were found under his fingernails and toenails, fueling speculation and adding weight to Hall's accusations.[3]

Later life edit

Bessels stayed with the Smithsonian Institution for several years in the 1870s, where he worked preparing the publication of the expedition's scientific results.[4] The most important of these results was the proof that Greenland was an island, deduced from tidal observations and the discovery of walnut drift wood, indicating a connection between the Greenland Sea and the Bering Sea.

The publication was planned for a total of three volumes, the first two of which were written by Bessels. However, only the first volume, Physical Observations, was ever published, and this was later suppressed for errors and never reissued. He planned a work on the Inuit, but all his manuscripts were destroyed by fire in 1885.[5]

Bessels later considered mounting his own Arctic expedition, but eventually decided against it. In 1875, he took part in another expedition to the American northwestern coast aboard the USS Saranac, but the voyage had to be interrupted after the ship was wrecked in the Seymour Narrows, between Vancouver Island and the mainland. In 1879, he published Die amerikanische Nordpol-expedition, an account of the Polaris expedition. This work was translated by historian William Barr and released as Polaris: The Chief Scientist's Recollections of the American North Pole Expedition in 2016.

Bessels died of a stroke in Stuttgart in 1888, at the age of 40.

References edit

Footnotes edit

- ^ Hantzsch 1902, p. 479.

- ^ Gilman 1905, p. 808.

- ^ Loomis 1971, p. 356.

- ^ Adler 1906, p. 133.

- ^ Wilson 1900, p. 251.

Bibliography edit

- Adler, C.; et al., eds. (1906). . The Jewish Encyclopedia. Vol. 3. New York: Funk & Wagnalls. p. 113.

- Barr, W., ed. (2016). The Chief Scientist's Recollections of the American North Pole Expedition. UCalgary Press. ISBN 9781552388754.

- Gilman, D. C.; et al., eds. (1905). . The New International Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co. p. 808.

- Hantzsch, V., ed. (1902). . Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (in German). Vol. 46. Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot. pp. 479–481.

- Henderson, B. B. (2001). Fatal North: Adventure and Survival Aboard USS Polaris. New York: New American Library. ISBN 9780451409355.

- Loomis, C. C. (1971). Weird and Tragic Shores: The Story of Charles Francis Hall. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780375755255.

- Moseley, H. N. (June 1881). "Dr. Bessels' Account of the "Polaris" Expedition". Nature. 24 (609): 194–197. Bibcode:1881Natur..24..194M. doi:10.1038/024194a0.

- Schroeder, K., ed. (1955). "Bessels, Emil Israel". Neue Deutsche Biographie (in German). Vol. 2. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot. p. 181.

- Wilson, J. G.; et al., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. Vol. 1. New York: D. Appleton & Co. p. 251.

External links edit

- Works by Emil Bessels at Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Works by Emil Bessels at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Emil Bessels at Open Library

- Works by or about Emil Bessels at Internet Archive