Eastern Christian monasticism is the life followed by monks and nuns of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Church of the East and some Eastern Catholic Churches.

History

editChristian monasticism began in the Eastern Mediterranean in Syria, Palestine and Egypt where the Desert Fathers pioneered traditions that would influence both the Hesychast traditions of Eastern Orthodoxy as well as Western monastic traditions pioneered by John Cassian and codified in the Rule of St Benedict.

The Early Church

editThe mystical and other-worldly nature of the Christian message very early laid the groundwork for the ascetical life. The example of the Old Testament Prophets, of John the Baptist and of Jesus himself, going into the wilderness to pray and fast set the example that was readily followed by the devout. In the early Christian literature evidence is found of individuals who embraced lives of celibacy and mortification for the sake of the Kingdom of Heaven, these individuals were not yet monks, as they had not renounced the world, but lived either in towns or near the outskirts of civilization.[citation needed] We also read of communities of virgins living a common life committed to celibacy and virtue. The accounts of some of these virgins are preserved in the martyrologies of the day.

The Founders

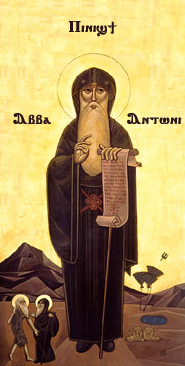

editThe beginning of monasticism per-se comes right at the end of the Great Persecution of Diocletian, and the founder is Saint Anthony the Great (251 - 356). As a young man he heard the words of the Gospel read in church: If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come and follow me (Matthew 19:21). St. Anthony was among the Desert Fathers - those who left the world to seek God in the silence and seclusion of the Egyptian desert. Around him gathered many disciples, whom he guided in the spiritual life. These first monks were hermits, solitaries who battled temptation alone in the wilderness.

As time went on, monks began to congregate into closer communities. Saint Pachomius (ca. 292 - 348) is regarded as the founder of cenobitic monasticism, wherein all live the common life together in a single place under the direction of a single Abbot. The first such monastery was in Tabennisi, Egypt.

Saint Theodore of Egypt, the principle disciple of St. Pachomius, succeeded him as head of the monastic community at Tabennisi. He would later go on to found a third type of monastic institution, the skete, as a "middle road" between anchorites and cenobites. A skete is composed of individual monastic dwellings surrounding a common church. Each monk lives by himself, or with one or two others, coming together only on Sundays and feast days. The rest of the time they spend working and praying alone.

On this threefold foundation all subsequent Christian monasticism was built.

Coptic monasticism

editAs the birthplace of monasticism, Egypt has continued the monastic tradition unbroken until the present day. After the Council of Chalcedon, the Alexandrian Patriarchate broke communion with those churches which accepted the council, and became what today is known as the Coptic Orthodox Church. Like the Byzantines, monasticism has continued to play a crucial role in the life of the church, and bishops are always chosen from among the ranks of monks. After the Islamic invasion in 639, the Egyptian Christians found themselves dispossessed in their own land. However, despite persecutions and intense pressure to convert, Coptic monasticism has survived, and some of the most ancient monastic communities in the history of Christianity continue to be inhabited to this day. A number of Coptic monasteries have also been established in the New World.

Ethiopia was one of the first nations to accept Christianity, officially converting in 341. King Abreha became the first sovereign in the world to engrave the Sign of the Cross on his coins. From the year 341 it was subject to the Patriarch of Alexandria, gaining its independence only in 1959. The church is officially known as the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church. In 480 the Nine Saints came from the Mediterranean world to establish Ethiopian monasticism which has continued to flourish despite wars and persecutions. Ancient and inaccessible monasteries are still occupied to this day throughout the Christian regions of the country. The Ethiopian Church also maintains monasteries in the Holy Land, most notably Deir Es-Sultan, on the roof of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem.

Syrian monasticism

editThe monastics of Armenia, Chaldea, and of the Syrian countries in general were influenced by neither the ecclesiastical nor imperial authority of Byzantium, and continued those observances which were known among them from the time of St. Anthony.

Monasticism was very popular in early Syrian and Mesopotamian Christianity, and originally all monks and nuns there were hermits, like the notable Isaac of Nineveh. Members of the Covenant, an early monastic community was active since the 3rd century in Edessa and its environs. About 350 Mar Awgin founded the first cenobitic monastery of Mesopotamia on Mount Izla above the city of Nisibis and monastic communities began to thrive. An important personality was Saint Simeon Stylites, an ascetic who lived for 37 years on pillar close to Aleppo. A monastery was later founded around the column where he had lived.

Under pressure from their Zoroastrian rulers, the Synod of Beth Lapat in 484 declared that the teaching of Nestorius was to be the official doctrine of the Assyrian Church of the East, and decreed that all monks and nuns should marry. This severely weakened the church and spiritual life declined. Some opponents to this decision left altogether and joined the newly established Monophysite church.

This decision was reverted in 553, and in 571 Abraham the Great of Kashkar founded a new monastery on Mt. Izla with strict rules. The third abbot of this monastery was his student Babai the Great (551 - 628). Babai finally drove out the married monks from Mt. Izla, and as "visitor of the monasteries of the north" ensured that the monastic ideal was taken seriously throughout northern Mesopotamia.

Especially in the region of the Amanos Mountains, also called the Black Mountain, many monasteries by Armenian, Jacobite, Georgian, Melkite and in the 12th century Latin Christian communities flourished for several centuries.[1] Close to Antioch was also the so-called Wondrous Mountain which hosted the Monastery of Saint Simeon Stylites the Younger.

Armenian monasticism

editIn 301, Armenia became the first sovereign nation to officially accept Christianity as a state religion.[2] The Armenian Apostolic Church eventually became a great defender of Armenian nationalism.

In 451 the Armenian church rejected the Council of Chalcedon.[3] and today is a part of the Oriental Orthodox communion (not to be confused with the Eastern Orthodox communion). The first Catholicos of the Armenian church was Saint Gregory the Illuminator.[4] St. Gregory soon withdrew to the desert to live as a hermit, and his youngest son, Aristakes, was appointed bishop and head of the Armenian Church. Over the centuries of waxing and waning influence, persecution, and independence of the Armenian nation, monasticism remained a central aspect of their spiritual life.

The Armenian church has both married (secular) and monastic (celibate) clergy. Armenian monks follow much the same monastic tradition as Coptic and Byzantine monastics, but are much stricter in the matter of fasting. The novitiate lasts eight years. A Hieromonk, or celibate priest, declares a vow of celibacy the evening of the same day he is ordained and is given a veghar (Armenian: վեղար), a special head-cover, which symbolizes his renunciation of worldly things. A celibate priest is given the title of Monk (Armenian: աբեղա abegha). Upon successful completion and defense of a written thesis, on a topic of his choosing, the Monk receives the rank of Archimandrite (Armenian: վարդապետ vardapet). This indicates that he is a “Doctor” of the Church and receives the right to carry the staff of an Archimandrite. A higher rank of Senior Archimandrite (Dzayraguyn Vardapet) can be granted after completing and defending a doctoral thesis. The rank can only be granted by Bishops who themselves have attained the rank of Senior Archimandrite. The bishops are elected from among those celibate priests who have achieved the rank of archimandrite.

Most Armenian bishops live in monasteries. Etchmiadzin, the residence of the Catholikos of all Armenians, is the spiritual center of the Armenian Church. There is also a Catholicos of Cilicia, who resides in Antilyas in Lebanon, and leads the churches belonging to the Holy See of Cilicia. Since 1461 there has been an Armenian Patriarch of Constantinople. The Armenians possess the huge monastery of St. James, the centre of the Armenian Quarter of Jerusalem, where their Patriarch of Jerusalem lives, and the convent of Deir asseituni on Mount Zion with numerous nuns.

At present, there are three monastic brotherhoods in the Armenian Church: the Brotherhood of the Mother See of Holy Etchmiadzin, the Brotherhood of St. James at the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, and the Brotherhood of the Holy See of Cilicia. Each Armenian celibate priest becomes a member of the brotherhood in which he has studied and ordained in or under the jurisdiction of which he has served. The brotherhood makes decisions concerning the inner affairs of the monastery. Each brotherhood elects two delegates who take part in the National Ecclesiastical Assembly.

The Mechitarists (Armenian: Մխիթարեան), also spelled Mekhitarists, are a congregation, founded in 1712 by Mechitar, of Armenian Benedictine monks in communion with the Catholic Church. They are best known for their series of scholarly publications of ancient Armenian versions of otherwise lost ancient Greek texts.

Byzantine monasticism

editSt. Basil the Great

editSaint Basil the Great (c. 330 - 379) is one of the most important influences on both Byzantine and Western monasticism. Before forming his own monastic community, he visited Egypt, Mesopotamia, Palestine and Syria, observing the monastic life and learning both from the positive and negative examples he encountered. He later composed his Asketikon for the members of the monastery he founded about the year 356 on the banks of the Iris river in Cappadocia. St Basil's work entailed two sets of monastic regulations: the Lesser Asketikon and the Greater Asketikon. Correspondence exists between him and St. Gregory Nazianzen which gives further insight into the type of monastic life he established.

St. Theodore the Studite

editThe monks, as a rule, enjoyed the favor of the emperors and patriarchs, but during the iconoclastic persecution they suffered terribly for the orthodoxy of their faith; the stand they took in this aroused the anger of the imperial powers and many were martyred for the faith, monasticism itself (not merely individual monks) became the target of the heretical emperors. Many of them were condemned to exile, and some took advantage of this condemnation to reorganize their religious life in Italy. Ironically, St. John of Damascus, living in a Moslem nation was independent of the iconoclast emperors and could defend the faith from afar.

The second half of the 8th century seems to have been a time of very general decadence; but about the year 800 St. Theodore the Studite (c. 758 - c. 826)—destined to be one of the most creative names in Eastern monasticism—became abbot of the monastery of St. John the Baptist, called the "Studium" (founded at Constantinople in the fifth century). He set himself to reform his monastery and restore St. Basil's spirit in its primitive vigour. But to effect this, and to give permanence to the reformation, he saw that there was need of a more practical code of laws to regulate the details of the daily life, as a supplement to St Basil's teachings. He therefore drew up constitutions, afterwards codified, which became the norm of the life at the Studium monastery, and gradually spread thence to the monasteries of the rest of the Eastern Roman Empire. At the same time the monastery was an active center of intellectual and artistic life and a model which exercised considerable influence on monastic observances in the East. Thus to this day the Asketikon of Basil and the Constitutions of Theodore, along with the canons of the Councils, constitute the chief part of Greek and Slavic monastic tradition.

Later Byzantine monasticism

editMonastic life on Mount Athos was founded towards the close of the 10th century through the aid of the Emperor Basil the Macedonian and became the largest and most celebrated of all the monastic centers of the Eastern Roman Empire. The peninsula is actually an independent monastic republic, governed by twenty "Sovereign Monasteries", with its own elected president (protos) and governing council. Mount Athos is the site of innumerable priceless cultural and spiritual treasures, and up to this day it is considered the capital of Orthodox monasticism.

The Saint Catherine's Monastery on Mount Sinai in Egypt was inhabited by hermits from the early days of monasticism. But the monastery as it is now was built by order of Emperor Justinian I between 527 and 565, enclosing the Chapel of the Burning Bush which had been built by St. Helena, the mother of St. Constantine the Great, at the site where Moses is supposed to have seen the burning bush. The site has been inhabited by monks ever since and is sacred to three major world religions – Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Many sacred icons there escaped the ravages of iconoclasm because of the remoteness of the location. Probably the most well-known item to come from the monastery is the Codex Sinaiticus, a 4th-century manuscript of the Septuagint which is of enormous value for textual research of the scriptures.

Notable Byzantine monks include:

- Leontius of Byzantium (d. 543), author of a treatise against the Nestorians and Eutychians;

- St. Sophronius, Patriarch of Jerusalem (d. 638), one of the most vigorous adversaries of the Monothelite heresy;[5]

- St. Maximus the Confessor, Abbot of Chrysopolis (d. 662), the most brilliant representative of Byzantine monasticism in the seventh century, who in his writings and letters steadily combated the partisans of the doctrines of Monothelitism;[6]

- St. John Damascene (d. 749), together with St. Theodore the Studite defender of the veneration of icons, whose works include theological, ascetic, hagiographical, liturgical, and historical writings;[7]

- Saint Gregory Palamas (1296–1359), who defended the tradition of hesychasm;

- Saint Paisius Velichkovsky (1722–1794), responsible for the renewal of monastic life in the 18th century, on Mount Athos, Romania and Imperial Russia.

The Byzantine monasteries furnish a long line of historians who were also monks: John Malalas, whose hronographia[8] served as a model for Eastern chroniclers; Georgius Syncellus, who wrote a "Selected Chronographia"; his friend and disciple Theophanes (d. 817), Abbot of the "Great Field" near Cyzicus, the author of another Chronographia;[9] the Patriarch Nikephoros, who wrote (815 – 829) an historical Breviarium (a Byzantine history), and an "Abridged Chronographia";[10] George the Monk, whose Chronicle stops at 842 AD.[11]

There were, besides, a large number of monks, hagiographers, hymnologists, and poets who had a large share in the development of the Greek Liturgy. Among the authors of hymns may be mentioned: St. Maximus the Confessor; St. Theodore the Studite; St. Romanus the Melodist; St. Andrew of Crete; St. John Damascene; Cosmas of Jerusalem, and St. Joseph the Hymnographer.

Fine penmanship and the copying of manuscripts were held in honor among the Byzantines. Among the monasteries which excelled in the art of copying were the Studium, Mount Athos, the monastery of the Isle of Patmos and that of Rossano in Sicily; the tradition was continued later by the monastery of Grottaferrata near Rome. These monasteries, and others as well, were studios of religious art where the monks toiled to produce miniatures, manuscripts, paintings, and goldsmith work. The triumph of Orthodoxy over the iconoclastic heresy infused an extraordinary enthusiasm into this branch of their labors.

Byzantine monasticism in Ukraine

editFollowing the Union of Brest and partitions of Poland, the Ruthenian Church was catholicized and later dissolved by the Russian authorities. All of its property including churches and monasteries were transferred to the Russian Orthodox Church. The remaining eparchies of the Ruthenian Church that were kept by the Austrian Empire were reorganized into the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.

Following the Union Brest which catholicized the Ruthenian Church, there was established a religious order of Basilians by Jazep Rutsky. In 20th century Andrey Sheptytskyi revived another religious orders of Studites. Both orders follow Byzantine-rite monasticism.

Slavic Monasteries

editSerbia

edit- Saint Sava of Serbia 1169 - 1236

Russia

editSt. Anthony of Kiev, St. Theodosius of Kiev, St. Sergius of Radonezh, St. Seraphim of Sarov and Saint Ambrose of Optina are among the most highly venerated monks in Russia.

Some Orthodox Christian Monasteries in the United States

editAs of December 2015 there were 79 Orthodox Christian monasteries in the United States of America, 40 monastic communities for men and 39 for women, with 573 monastics (monks, nuns, and novices), 308 men and 265 women.[12]

Of these 79 monasteries, three are:

References

edit- ^ Hamilton, Bernard; Jotischky, Andrew (22 Oct 2020). Latin and Greek Monasticism in the Crusader States. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781108915922.

- ^ "Information about Armenia on nationalgeographic.com". Archived from the original on 2007-01-30. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ^ "Armenian Church History and Doctrine". Archived from the original on 2009-07-30. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ^ "The Holy City and the Mother Church of St. Etchmiadzin". Archived from the original on 2017-08-23. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ^ Patrologia Graecae, LXXXVII, 3147–4014

- ^ Patrologia Graecae, XC and XCI.

- ^ Patrologia Graecae, XCIX.

- ^ Patrologia Graecae, XCVII, 9–190.

- ^ Patrologia Graecae, CVIII.

- ^ Patrologia Graecae, C, 879–991.

- ^ Patrologia Graecae, CX.

- ^ Alexei Krindatch, ed. (2016). Atlas of American Orthodox Christian Monasteries (PDF). Brookline, Massachusetts, USA: Holy Cross Orthodox Press. p. xii. ISBN 9781935317616.

Sources

edit- Thomas, John P. (1987). Private Religious Foundations in the Byzantine Empire. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks. ISBN 9780884021643.