Traditional courtship in the Philippines is described as a "far more subdued and indirect"[1] approach compared to Western or Westernized cultures. It involves "phases" or "stages" inherent to Philippine society and culture.[1][2] Evident in courtship in the Philippines is the practice of singing romantic love songs, reciting poems, writing letters, and gift-giving.[3] This respect extends to the Filipina's family members. The proper rules and standards in traditional Filipino courtship are set by Philippine society.[4]

General overview edit

Often, a Filipino male suitor expresses his interest to a woman in a discreet and friendly manner in order to avoid being perceived as very "presumptuous or aggressive" or arrogant.[2] Although having a series of friendly dates is the normal starting point in the Filipino way of courting, this may also begin through the process of "teasing", a process of "pairing off" a potential teenage or adult couple. The teasing is done by peers or friends of the couple being matched. The teasing practice assists in his teasing phase actually helps in circumventing such an embarrassing predicament because formal courtship has not yet officially started can also have as many suitors, from which she could choose the man that she finally would want to date. Dating couples are expected to be conservative and not perform public displays of affection for each other. Traditionally, some courtship may last a number of years before the Filipino woman accepts her suitor as a boyfriend.[1][2][3] Conservativeness, together with repressing emotions and affection, was inherited by the Filipino woman from the colonial period under the Spaniards, a characteristic referred to as the Maria Clara attitude.[3]

After the girlfriend-boyfriend; pamamanhikan is known as tampa or danon to the Ilocanos, as pasaguli to the Palaweños, and as kapamalai to the Maranaos[5]). This is where and when the man and his parents formally ask the lady's hand[4] and blessings from her parents in order to marry. This is when the formal introduction of the man's parents and woman's parents happens. Apart from presents, the Cebuano version of the pamamanhikan includes bringing in musicians.[5] After setting the date of the wedding and the dowry,[4] the couple is considered officially engaged.[2] The dowry, as a norm in the Philippines, is provided by the groom's family.[4] For the Filipino people, marriage is a union of two families, not just of two persons. Therefore, marrying well "enhances the good name" of both families.[3]

Other courtship practices edit

Tagalog and Ilocos regions edit

Apart from the general background explained above, there are other similar and unique courting practices adhered to by Filipinos in other different regions of the Philippine archipelago. In the island of Luzon, the Ilocanos also perform serenading, known to them as tapat[5] (literally, "to be in front of" the home of the courted woman), which is similar to the harana[4] and also to the balagtasan of the Tagalogs. The suitor begins singing a romantic song, then the courted lady responds by singing too.[3] In reality, Harana is a musical exchange of messages which can be about waiting or loving or just saying no. The suitor initiates, the lady responds. As the Pamamaalam stage sets in, the suitor sings one last song and the haranistas disappear in the night.

Rooster courtship is also another form of courting in Luzon. In this type of courtship, the rooster is assigned that task of being a "middleman", a "negotiator", or a "go-between", wherein the male chicken is left to stay in the home of the courted to crow every single morning for the admired lady's family.[3]

In the province of Bulacan in Central Luzon, the Bulaqueños have a kind of courtship known as the naninilong (from the Tagalog word silong or "basement"). At midnight, the suitor goes beneath the nipa hut, a house that is elevated by bamboo poles, then prickles the admired woman by using a pointed object. Once the prickling caught the attention of the sleeping lady, the couple would be conversing in whispers.[3]

The Ifugao of northern Luzon practices a courtship called ca-i-sing (this practice is known as the ebgan to the Kalinga tribes and as pangis to the Tingguian tribes), wherein males and females are separated into "houses". The house for the Filipino males is called the Ato, while the house for Filipino females is known as the olog or agamang. The males visit the females in the olog – the "betrothal house" – to sing romantic songs. The females reply to these songs also through singing. The ongoing courtship ritual is overseen by a married elder or a childless widow who keeps the parents of the participating males and females well informed of the progress of the courtship process.[5]

After the courtship process, the Batangueños of Batangas has a peculiar tradition performed on the eve of the wedding. A procession, composed of the groom's mother, father, relatives, godfathers, godmothers, bridesmaids, and groomsmen, occurs. Their purpose is to bring the cooking ingredients for the celebration to the bride's home, where refreshments await them. When they are in the half process of the courtship, they are forced to make a baby[5]

Pangasinan region edit

In Pangasinan, the Pangasinenses utilizes the taga-amo, which literally means "tamer", a form of love potions or charms which can be rubbed to the skin of the admired. It can also be in the form of drinkable potions. The suitor may also resort to the use of palabas, meaning show or drama, wherein the Filipino woman succumbs to revealing her love to her suitor, who at one time will pretend or act as if he will be committing suicide if the lady does not divulge her true feelings.[3]

Apayao region edit

The Apayaos allow the practice of sleeping together during the night. This is known as liberal courtship or mahal-alay in the vernacular. This form of courting assists in assessing the woman's feeling for her lover.[3]

Palawan region edit

In Palawan, the Palaweños or Palawanons perform courtship through the use of love riddles. This is known as the pasaguli. The purpose of the love riddles is to assess the sentiments of the parents of both suitor and admirer. After this "riddle courtship", the discussion proceeds to the pabalic (can also be spelled pabalik), to settle the price or form of the dowry that will be received by the courted woman from the courting man.[3]

Visayas region edit

When courting, the Cebuanos also resort to serenading, which is known locally as balak. They also write love letters that are sent via a trusted friend or a relative of the courted woman. Presents are not only given to the woman being courted, but also to her relatives. Similar to the practice in the Pangasinan region, as mentioned above, the Cebuanos also use love potions to win the affection of the Filipino woman.[3]

People from Leyte performs the pangagad'[5] or paninilbihan or "servitude",[4] instead of paying a form of dowry[5] during the courtship period. In this form of courting, the Filipino suitor accomplishes household and farm chores for the family of the Filipino woman. The service normally lasts for approximately a year before the man and woman can get married.[3] The Tagalogs of Luzon also refers to this courtship custom as paninilbihan meaning "being of service", but is also referred to as subok meaning a trial or test period for the serving suitor. The Bicolanos of Luzon's Bicol region, call this custom as the pamianan.[5] The practice of performing paninilbihan, throwing the rice over bride and groom for prosperity, paying dowry, visiting a shrine to pray for fertility, etc. are among strong traces of continuity of Hindu influence in Philippines,[6] even the term "asawa" (from swami in sanskrit) for the spouse is a loan word from the Indian language sanskrit.[7]

Mindanao region edit

Reckless courtship, known in the vernacular as palabas, sarakahan tupul, or magpasumbahi, is practiced by the Tausog people of Mindanao. Similar to the palabas version practiced in Luzon island, a suitor would threaten to stab his heart while in front of the courted woman's father. If the father of the woman refuses to give his daughter's hand to the suitor, the suitor is smitten by a knife.[3]

The Bagobo, on the other hand, sends a knife or a spear as a gift to the home of the courted woman for inspection. Accepting the weapon is equivalent to accepting the Filipino man's romantic intention and advances.[3]

Pre-arranged marriages and betrothals are common to Filipino Muslims. These formal engagements are arranged by the parents of men and the women. This also involves discussions regarding the price and the form of the dowry.[3] The Tausog people proclaims that a wedding, a celebration or announcement known as the pangalay, will occur by playing percussive musical instruments such as the gabbang, the kulintang, and the agong. The wedding is officiated by an Imam. Readings from the Quran is a part of the ceremony, as well as the placement of the groom's fingerprint over the bride's forehead.[5]

19th-century Hispanic Philippines edit

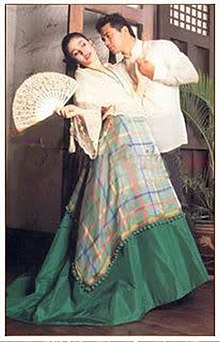

During the 19th century in Spanish Philippines, there was a set of body language expressed by courted women to communicate with their suitors. These are non-verbal cues which Ambeth Ocampo referred to as "fan language". These are called as such because the woman conveys her messages through silent movements that involve a hand-held fan. Examples of such speechless communication are as follows: a courted woman covering half of her face would like her suitor to follow her; counting the ribs of the folding fan sends out a message that the lady would like to have a conversation with her admirer; holding the fan using the right hand would mean the woman is willing to have a boyfriend, while carrying the fan with the left hand signifies that she already has a lover and thus no longer available; fanning vigorously symbolizes that the lady has deep feelings for a gentleman, while fanning slowly tells that the woman courted does not have any feelings for the suitor; putting the fan aside signals that the lady does not want to be wooed by the man; and the abrupt closing of a fan means the woman dislikes the man.[8]

Modern-day influences edit

Through the liberalism of modern-day Filipinos, there have been modifications of courtship that are milder than that in the West. Present-day Filipino courtship, as in the traditional form, also starts with the "teasing stage" conducted by friends. Introductions and meetings between prospective couples are now done through a common friend or whilst attending a party.[4] Modern technology has also become a part of present-day courting practises. Romantic conversations between both parties are now through cellular phones – particularly through texting messages – and the internet.[3] Parents, however, still prefer that their daughters be formally courted within the confines of the home, done out of respect to the father and mother of the single woman. Although a present-day Filipina wants to encourage a man to court her or even initiate the relationship,[3] it is still traditionally "inappropriate" for a suitor to introduce himself to an admired woman, or vice versa, while on the street. Servitude and serenading are no longer common, but avoidance of pre-marital sex is still valued.[4]

Other than the so-called modern Philippine courtship through texting and social media, there is another modern style that is not widely discussed in public discourse: North American pickup as documented by Neil Strauss in his book The Game: Penetrating the Secret Society of Pickup Artists. While there exist a few local companies that offer pickup training, it remains to be seen whether these methods will even gain widespread acceptance since these methods, along with the paradigm from which they are rooted, flout the values of most Filipinos.[citation needed]

See also edit

References edit

- ^ a b c Filipino Courtship Customs – How to court a Filipina, asiandatingzone.com

- ^ a b c d Alegre, Edilberto. Tuksuhan, Ligawan: Courtship in Philippine Culture, Tagalog Love Words (An Essay), Our loving ways Archived August 27, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, seasite.niu.edu

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Courtship in the Philippines Today, SarahGats's Blog, sarahgats.wordpress.com, March 29, 2009

- ^ a b c d e f g h Borja-Slark, Aileen. "Filipino Courtship: Traditional vs. Modern". Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved September 19, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Love and Romance Filipino Style Archived January 27, 2010, at the Wayback Machine and Family Structure Archived February 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine: The Betrothal House (Ifugao, Mountain Province), Courtship Through Poetry and Song (Ilocos province), The Eve of the Wedding (Province of Batangas), The Formal Proposal (Province of Cebu), Bride Service (Province of Leyte), The Wedding (Tausug), livinginthephilippines.com

- ^ Cecilio D. Duka, 2008, Struggle for Freedom, Rex Bookstore, p. 35.

- ^ M.c. Halili, 2004, Philippine History, Rex Bookstore, p. 49.

- ^ Ocampo, Ambeth R. Fan Language, Looking Back, Philippine Daily Inquirer, February 2, 2005, page 13, news.google.com