Calciphylaxis, also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy (CUA) or “Grey Scale”, is a rare syndrome characterized by painful skin lesions. The pathogenesis of calciphylaxis is unclear but believed to involve calcification of the small blood vessels located within the fatty tissue and deeper layers of the skin, blood clots, and eventual death of skin cells due to lack of blood flow.[1] It is seen mostly in people with end-stage kidney disease but can occur in the earlier stages of chronic kidney disease and rarely in people with normally functioning kidneys.[1] Calciphylaxis is a rare but serious disease, believed to affect 1-4% of all dialysis patients.[2] It results in chronic non-healing wounds and indicates poor prognosis, with typical life expectancy of less than one year.[1]

| Calciphylaxis | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Calcific Uremic Arteriolopathy (CUA) |

| |

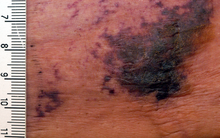

| Calciphylaxis on the abdomen of a patient with end stage kidney disease. Markings are in cm. | |

| Specialty | Nephrology |

| Symptoms | Painful necrotic skin lesions |

| Complications | Infection, sepsis |

| Risk factors | Female sex, obesity, use of Warfarin, protein C or S deficiency, hypoalbuminemia, diabetes mellitus, use of vitamin D derivatives (calcitriol, systemic steroids) |

| Diagnostic method | Clinical, skin biopsy may aid diagnosis |

| Treatment | Dialysis, analgesics, surgical wound debridement, parathyroidectomy |

| Medication | Sodium thiosulfate |

| Prognosis | 1-year mortality rate is 45–80% |

| Frequency | 1-4% of all dialysis patients in the U.S. |

Calciphylaxis is one type of extraskeletal calcification. Similar extraskeletal calcifications are observed in some people with high levels of calcium in the blood, including people with milk-alkali syndrome, sarcoidosis, primary hyperparathyroidism, and hypervitaminosis D. In rare cases, certain medications such as warfarin can also result in calciphylaxis.[3]

Signs and symptoms edit

The first skin changes in calciphylaxis lesions are mottling of the skin and induration in a livedo reticularis pattern. As tissue thrombosis and infarction occurs, a black, leathery eschar in an ulcer with adherent black slough develops. Surrounding the ulcers is usually a plate-like area of indurated skin.[4] These lesions are always extremely painful and most often occur on the lower extremities, abdomen, buttocks, and penis. Lesions are also commonly multiple and bilateral.[1] Because the tissue has infarcted, wound healing seldom occurs, and ulcers are more likely to become secondarily infected. Many cases of calciphylaxis lead to systemic bacterial infection and death.[5]

Calciphylaxis is characterized by the following histologic findings:

- systemic medial calcification of the arteries, i.e. calcification of tunica media. Unlike other forms of vascular calcifications (e.g., intimal, medial, valvular), calciphylaxis is characterized also by

- small vessel mural calcification with or without endovascular fibrosis, extravascular calcification and vascular thrombosis, leading to tissue ischemia (including skin ischemia and, hence, skin necrosis).

Heart of stone edit

Severe forms of calciphylaxis may cause diastolic heart failure from cardiac calcification, called heart of stone. Widespread intravascular calcification typical of calciphylaxis lesions occur in the myocardium and prevent normal diastolic filling of the ventricles.[6]

Cause edit

The cause of calciphylaxis is unknown. Calciphylaxis is not a hypersensitivity reaction (i.e., allergic reaction) leading to sudden local calcification. The disease is also known as calcific uremic arteriolopathy; however, the disease is not limited to patients with kidney failure. The current belief is that in end-stage kidney disease, abnormal calcium and phosphate homeostasis result in the deposition of calcium in the vessels, also known as metastatic calcification. Once the calcium has been deposited, a thrombotic event occurs within the lumen of these vessels, resulting in occlusion of the vessel and subsequent tissue infarction. Specific triggers for either thrombotic or ischemic events are unknown.[7] Adipocytes have been shown to calcify vascular smooth muscle cells when exposed to high phosphate levels in vitro, mediated by vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) and leptin released by adipocytes. Given that calciphylaxis tends to affect adipose tissue, this may be a contributing explanation.[8] Another hypothesis has been proposed, that vitamin K deficiency contributes to the development of calciphylaxis. Vitamin K acts as an inhibitor of calcification in vessel walls by activating matrix Gla protein (MGP), which in turn inhibits calcification. End-stage kidney disease patients are more likely to have vitamin K deficiency due to dietary restrictions meant to limit potassium and sodium. Many end-stage kidney disease patients are also on a medication called warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist, that limits vitamin K recycling in the body.[8]

Reported risk factors include female sex, obesity, elevated calcium-phosphate product, medications such as warfarin, vitamin D derivatives (e.g. calcitriol, calcium-based binders, or systemic steroids), protein C or S deficiency, low blood albumin levels, and diabetes mellitus.[9] Patients who require or have undergone any type of vascular procedures are also at increased risk for poor outcomes.[10]

Diagnosis edit

There is no diagnostic test for calciphylaxis. The diagnosis is a clinical one. The characteristic lesions are the ischemic skin lesions (usually with areas of skin necrosis). The necrotic skin lesions (i.e. the dying or already dead skin areas) typically appear as violaceous (dark bluish purple) lesions and/or completely black leathery lesions.[11] They can be extensive and found in multiples. The suspected diagnosis can be supported by a skin biopsy, usually a punch biopsy, which shows arterial calcification and occlusion in the absence of vasculitis. Excisional biopsy should not be done due to increased risk of further ulceration and necrosis.[1] Bone scintigraphy can be performed in cases where skin biopsy is contraindicated. Results of the study show increased tracer accumulation in the soft tissues.[12] In certain patients, an anti-nuclear antibody test may play a role in diagnosis of calciphylaxis.[13] Plain radiography and mammography may also show calcifications but these tests are less sensitive.[8] Laboratory studies, such as phosphate levels, calcium levels, and parathyroid levels, are nonspecific and unhelpful for diagnosis of calciphylaxis.[1]

Treatment edit

The treatment of calciphylaxis requires a multidisciplinary approach, using the knowledge of nephrologists, plastic surgeons, dermatologists, and wound care specialists working together to manage the disease and its outcomes.[8] The key to treating calciphylaxis is prevention via rigorous control of phosphate and calcium balance and management of risk factors in patients who have increased chances of developing calciphylaxis. There is no specific treatment. Most treatment recommendations lack significant data, and none are internationally recognized as the standard of care. It is generally accepted to apply a multi-pronged approach to each patient.[citation needed]

Analgesia and wound management edit

Pain management and choice of analgesia is a challenging task in managing calciphylaxis. Pain is one of the most severe and pervasive symptoms of the disease and can be unresponsive to high-dose opioids. Fentanyl and methadone are preferred analgesics over morphine, since morphine breakdown produces active metabolites that accumulate in the body of patients with kidney failure.[8] Adjunct medications such as gabapentin and ketamine may also be used for analgesia. In refractory cases, spinal anesthetics (nerve blocks) can be used for more comprehensive pain relief.[1] Wound care for calciphylaxis lesions involves using appropriate dressings, wound debridement (removal of dead tissue), and prevention of infection. Wound infections lead to sepsis, which is one of the leading causes of death in patients with calciphylaxis. Surgical wound debridement carries increased risk for infection, so it should only be considered as therapy if the survival benefit outweighs the chances of continued wound non-healing and pain.[1]Hyperbaric oxygen therapy may also be considered. There are some smaller retrospective studies that show the use of hyperbaric oxygen in improving delivery of oxygen to wounds, which improves blood flow and helps with wound healing.[14][1]

Risk factor mitigation edit

Most patients with calciphylaxis are already on hemodialysis, or simply dialysis, but the length or frequency of sessions may be increased. The majority of dialysis patients are on a 4-hour three times per week schedule. Indications for increasing dialysis session length or frequency include electrolyte and mineral abnormalities, such as hyperphosphatemia, hypercalcemia, and hyperparathyroidism, all of which are also risk factors for development of calciphylaxis.[1] Peritoneal dialysis patients should also transition to hemodialysis, as only hemodialysis carries the added benefit of better phosphate and calcium control.[15] Surgical parathyroidectomy is also recommended for those who have difficulty managing phosphate and calcium level balance. However, risks include development of post-operative hungry bone syndrome (HBS), a disease state that causes low calcium and requires use of calcium supplementation and calcitriol, which should be avoided in patients with end-stage kidney disease and calciphylaxis.[1]

Pharmacotherapy edit

Sodium thiosulfate is commonly prescribed for treatment in patients with calciphylaxis. The actual mechanism of the drug is unknown, but several explanations have been proposed, including chelation of calcium, vasodilation, antioxidant properties, and restoration of endothelial function. Adverse effects of sodium thiosulfate include high anion gap metabolic acidosis and high sodium levels (hypernatremia).[16]Bisphosphonates are a popular choice for the treatment of osteoporosis, but they have also been used to treat calciphylaxis even though the exact mechanism in calciphylaxis is unknown. They are most beneficial in patients who have a genetic ENPP1 deficiency and have been shown to slow development of calciphylaxis lesions in a small prospective study.[1]Cinacalcet (medication parathyroidectomy) is an oral medication that can be used to suppress the parathyroid glands for patients who may not be able to undergo surgical parathyroidectomy. Vitamin K supplementation has also been shown to slow development of calcification in coronary arteries and the aortic valve in older patients.[17] The ability of vitamin K supplementation to slow calcification of blood vessels in calciphylaxis is not well-studied. Warfarin, a vitamin K antagonist discussed above, should be discontinued if possible.[8]

Other acceptable treatments may include one or more of the following:

- Clot-dissolving agents (tissue plasminogen activator)

- Maggot larval debridement

- Correction of the underlying plasma calcium and phosphorus abnormalities (lowering the Ca x P product below 55 mg2/dL2)

- Avoiding further local tissue trauma (including avoiding all subcutaneous injections, and all not-absolutely-necessary infusions and transfusions)

- Patients who have received kidney transplants also receive immunosuppression. Considering lowering the dose of or discontinuing the use of immunosuppressive drugs in people who have received kidney transplants and continue to have persistent or progressive calciphylactic skin lesions can contribute to an acceptable treatment of calciphylaxis.

- A group in 2013 reported plasma exchange effective and proposed a serum marker and perhaps a mechanistic mediator (calciprotein)[18]

Prognosis edit

Overall, the clinical prognosis for calciphylaxis is poor. The 1-year mortality rate in patients who have end-stage kidney disease is 45-80%.[1] Median survival in patients who do not have end-stage kidney disease is 4.2 months.[19] Response to treatment is not guaranteed. The most common cause of death in calciphylaxis patients is sepsis, severe infection originating from a non-healing ulcer.[1]

Epidemiology edit

Calciphylaxis most commonly occurs in patients with end-stage renal disease who are on hemodialysis or who have recently received a kidney transplant. When reported in patients without end-stage renal disease (such as in earlier stages of chronic kidney disease or in normal kidney function), it is called non-uremic calciphylaxis by Nigwekar et al.[20] Non-uremic calciphylaxis has been observed in patients with primary hyperparathyroidism, breast cancer (treated with chemotherapy), liver cirrhosis (due to hazardous alcohol use), cholangiocarcinoma, Crohn's disease, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). Calciphylaxis, regardless of etiology, has been reported at an incidence of 35 in 10,000 dialysis patients per year in the United States,[15] 4 in 10,000 patients in Germany,[21] and less than 1 in 10,000 patients in Japan.[22] It is unknown whether the higher incidence in the United States is due to genuinely higher incidence or due to underreporting in other countries. Annual incidence in kidney transplant patients and in non-uremic calciphylaxis patients is also unknown. The median age of patients at diagnosis of calciphylaxis is 60 years and the majority of these patients are women (60-70%).[23] The location of lesions, central (located on the trunk) or peripheral (located on the extremities), is dependent on several risk factors. Central lesions are associated with younger patients, patients with a higher body mass index, and a higher risk of death than those who have peripheral-only lesions.[23]

References edit

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Nigwekar, SU; Thadhani, R; Brandenburg, VM (May 2018). "Calciphylaxis". New England Journal of Medicine. 378 (18): 1704–1714. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1505292. PMID 29719190.

- ^ Angelis, M; Wong, LM; Wong, LL; Myers, S (1997). "Calciphylaxis in patients on hemodialysis: A prevalence study". Surgery. 122 (6): 1083–1090. doi:10.1016/S0039-6060(97)90212-9. PMID 9426423.

- ^ Yu, Wesley Yung-Hsu; Bhutani, Tina; Kornik, Rachel; Pincus, Laura B.; Mauro, Theodora; Rosenblum, Michael D.; Fox, Lindy P. (1 March 2017). "Warfarin-Associated Nonuremic Calciphylaxis". JAMA Dermatology. 153 (3): 309–314. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.4821. PMC 5703198. PMID 28099971.

- ^ Zhou Qian; Neubauer Jakob; Kern Johannes S; Grotz Wolfgang; Walz Gerd; Huber Tobias B (2014). "Calciphylaxis". The Lancet. 383 (9922): 1067. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60235-X. PMID 24582472. S2CID 208788507.

- ^ Wolff, Klaus; Johnson, Richard; Saavedra, Arturo (2013-03-06). Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology (7th ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-07-179302-5.

- ^ Tom, Cindy W.; Talreja, Deepak R. (March 2006). "Heart of Stone". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 81 (3): 335. doi:10.4065/81.3.335. PMID 16529137.

- ^ Wilmer, William; Magro, Cynthia (2002). "Calciphylaxis: Emerging Concepts in Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment". Seminars in Dialysis. 15 (3): 172–186. doi:10.1046/j.1525-139X.2002.00052.x. PMID 12100455. S2CID 45511014.

- ^ a b c d e f Chang, John J. (May 2019). "Calciphylaxis: Diagnosis, Pathogenesis, and Treatment". Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 32 (5): 205–215. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000554443.14002.13. PMID 31008757. S2CID 128352461.

- ^ Arseculeratne, G; Evans, AT; Morley, SM (2006). "Calciphylaxis – a topical overview". Journal of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology. 20 (5): 493–502. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2006.01506.x. PMID 16684274. S2CID 20586832.

- ^ Lal, Geeta; Nowell, Andrew G.; Liao, Junlin; Sugg, Sonia L.; Weigel, Ronald J.; Howe, James R. (December 2009). "Determinants of survival in patients with calciphylaxis: A multivariate analysis". Surgery. 146 (6): 1028–1034. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2009.09.022. PMID 19958929.

- ^ Baby, Deepak; Upadhyay, Meenakshi; Joseph, MDerick; Asopa, SwatiJoshi; Choudhury, BasantaKumar; Rajguru, JagadishPrasad; Gupta, Shivangi (2019). "Calciphylaxis and its diagnosis: A review". Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care. 8 (9): 2763–2767. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_588_19. PMC 6820424. PMID 31681640.

- ^ Araya CE, Fennell RS, Neiberger RE, Dharnidharka VR (2006). "Sodium thiosulfate treatment for calcific uremic arteriolopathy in children and young adults". Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 1 (6): 1161–6. doi:10.2215/CJN.01520506. PMID 17699342.

- ^ Rashid RM, Hauck M, Lasley M (Nov 2008). "Anti-nuclear antibody: a potential predictor of calciphylaxis in non-dialysis patients". J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 22 (10): 1247–8. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2008.02606.x. PMID 18422539. S2CID 37539737.

- ^ Edsell ME, Bailey M, Joe K, Millar I (2008). "Hyperbaric oxygen therapy in the treatment of skin ulcers due to calcific uraemic arteriolopathy: experience from an Australian hyperbaric unit". Diving and Hyperbaric Medicine. 38 (3): 139–44. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ a b Nigwekar, Sagar U.; Zhao, Sophia; Wenger, Julia; Hymes, Jeffrey L.; Maddux, Franklin W.; Thadhani, Ravi I.; Chan, Kevin E. (November 2016). "A Nationally Representative Study of Calcific Uremic Arteriolopathy Risk Factors". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 27 (11): 3421–3429. doi:10.1681/ASN.2015091065. PMC 5084892. PMID 27080977.

- ^ Udomkarnjananun, Suwasin; Kongnatthasate, Kitravee; Praditpornsilpa, Kearkiat; Eiam-Ong, Somchai; Jaber, Bertrand L.; Susantitaphong, Paweena (February 2019). "Treatment of Calciphylaxis in CKD: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Kidney International Reports. 4 (2): 231–244. doi:10.1016/j.ekir.2018.10.002. PMC 6365410. PMID 30775620.

- ^ Shea, M Kyla; O’Donnell, Christopher J; Hoffmann, Udo; Dallal, Gerard E; Dawson-Hughes, Bess; Ordovas, José M; Price, Paul A; Williamson, Matthew K; Booth, Sarah L (1 June 2009). "Vitamin K supplementation and progression of coronary artery calcium in older men and women". The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 89 (6): 1799–1807. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27338. PMC 2682995. PMID 19386744.

- ^ Cai MM, Smith ER, Brumby C, McMahon LP, Holt SG (2013). "Fetuin-A-containing calciprotein particle levels can be reduced by dialysis, sodium thiosulphate and plasma exchange. Potential therapeutic implications for calciphylaxis?". Nephrology (Carlton). 18 (11): 724–7. doi:10.1111/nep.12137. PMID 24571743. S2CID 5252893.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Bajaj, Richa; Courbebaisse, Marie; Kroshinsky, Daniela; Thadhani, Ravi I.; Nigwekar, Sagar U. (September 2018). "Calciphylaxis in Patients With Normal Renal Function: A Case Series and Systematic Review". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 93 (9): 1202–1212. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2018.06.001. PMID 30060958. S2CID 51883048.

- ^ Nigwekar SU, Wolf M, Sterns RH, Hix JK (Jul 2008). "Calciphylaxis from nonuremic causes: a systematic review". Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 3 (4): 1139–43. doi:10.2215/cjn.00530108. PMC 2440281. PMID 18417747.

- ^ Brandenburg, Vincent M.; Kramann, Rafael; Rothe, Hansjörg; Kaesler, Nadine; Korbiel, Joanna; Specht, Paula; Schmitz, Sophia; Krüger, Thilo; Floege, Jürgen; Ketteler, Markus (29 January 2016). "Calcific uraemic arteriolopathy (calciphylaxis): data from a large nationwide registry". Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation. 32 (1): 126–132. doi:10.1093/ndt/gfv438. PMID 26908770.

- ^ Hayashi, Matsuhiko (August 2013). "Calciphylaxis: diagnosis and clinical features". Clinical and Experimental Nephrology. 17 (4): 498–503. doi:10.1007/s10157-013-0782-z. PMID 23430392. S2CID 28517319.

- ^ a b McCarthy, James T.; el-Azhary, Rokea A.; Patzelt, Michelle T.; Weaver, Amy L.; Albright, Robert C.; Bridges, Alina D.; Claus, Paul L.; Davis, Mark D.P.; Dillon, John J.; El-Zoghby, Ziad M.; Hickson, LaTonya J.; Kumar, Rajiv; McBane, Robert D.; McCarthy-Fruin, Kathleen A.M.; McEvoy, Marian T.; Pittelkow, Mark R.; Wetter, David A.; Williams, Amy W. (October 2016). "Survival, Risk Factors, and Effect of Treatment in 101 Patients With Calciphylaxis". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 91 (10): 1384–1394. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.025. PMID 27712637.

Further reading edit

- Weenig RH (2008). "Pathogenesis of calciphylaxis: Hans Selye to nuclear factor kappa-B". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 58 (3): 458–71. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.12.006. PMID 18206262.

- Weenig RH, Sewell LD, Davis MD, McCarthy JT, Pittelkow MR (2007). "Calciphylaxis: natural history, risk factor analysis, and outcome". J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 56 (4): 569–79. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.065. PMID 17141359.

- Li JZ, Huen W (2007). "Images in clinical medicine. Calciphylaxis with arterial calcification". N. Engl. J. Med. 357 (13): 1326. doi:10.1056/NEJMicm060859. PMID 17898102.