Barton Hartshorn is a civil parish about 4 miles (6.4 km) southwest of Buckingham in Buckinghamshire, within the Buckinghamshire Council unitary authority area. Its southern boundary is a brook called the Birne, and this and the parish's western boundary form part of the county boundary with Oxfordshire. At the 2011 Census the population of the parish was included in the civil parish of Chetwode

| Barton Hartshorn | |

|---|---|

St. James' parish church | |

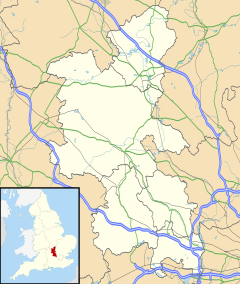

Location within Buckinghamshire | |

| Population | 88 (Mid-2010 pop est)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SP6431 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Buckingham |

| Postcode district | MK18 |

| Dialling code | 01280 |

| Police | Thames Valley |

| Fire | Buckinghamshire |

| Ambulance | South Central |

| UK Parliament | |

The toponym "Barton" is derived from the Old English for "Barley Farm", and is a common place name in England. In the 11th century it was recorded as Bertone.[2] In the 15th century it was recorded as Barton Hertishorne and Beggars Barton, and in the 16th century it was Little Barton.[2] "Hartshorn" comes from a separate hamlet in the same parish and is thought[by whom?] to refer to the shape of the land locally: it[clarification needed] lies in the shape of a deer's horn.[citation needed]

Manor edit

Before the Norman Conquest of England Wilaf, a thegn of Earl Leofwine Godwinson, held the manor.[2] The Domesday Book of 1086 records that it was one of the extensive landholdings of Odo, Bishop of Bayeux.[2] However, by then Odo had already been imprisoned for disobeying William I and forfeited his estates to the Crown.[2]

In the 13th century both Nutley Abbey in Long Crendon and Osney Abbey in Oxford held land at Barton.[2] Both abbeys retained their estates here until the dissolution of the monasteries in the late 1530s,[2] when they were required to surrender them to the Crown. After the dissolution, Nutley's land at Barton was granted to the same secular owner as the adjacent manor of Chetwode, and the two descended together until the 20th century.[2]

Part of the manor house is 17th century and a stone on the west gable is inscribed with the date 1635.[2][3] Surviving 17th century features include some mullioned windows, a fireplace, staircase, and panelling.[3] Alterations and major extensions to the house made in 1903 and 1908 were designed by the architect was Robert Lorimer.[3]

Parish church edit

The nave of the Church of England parish church of Saint James may be 13th century: it has a 13th-century lancet window in the west wall and a 13th-century doorway (not in its original position) in the south wall.[2] The windows either side of the south door are 14th century, and so too may be the north door.[2] The blocked west doorway is late 15th or early 16th century and in the north wall are two 16th century windows. The south porch may be 17th century. The chancel was added in the 19th century and the transepts in 1841.[2]

Economic history edit

The parish's common lands were enclosed by an Act of Parliament passed in 1812.[2]

In 1899 the Great Central Railway completed its main line to London through the southernmost part of the parish. The nearest station was Finmere for Buckingham, which was just over the Oxfordshire county boundary on the main road between Buckingham and Bicester and only 3⁄4 mile (1.2 km) from Barton Hartshorn. The station was 5 miles (8 km) from Buckingham, more than 1 mile (1.6 km) from Finmere and was actually in Shelswell parish next to the village of Newton Purcell. In about 1922 the Great Central renamed the station Finmere. British Railways closed the station in 1963 and the line in 1966.

References edit

Sources edit

- Page, W.H., ed. (1927). A History of the County of Buckingham, Volume 4. Victoria County History. pp. 147–149.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1973) [1966]. Buckinghamshire. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 60–61. ISBN 0-14-071019-1.

External links edit

- Media related to Barton Hartshorn at Wikimedia Commons

- Barton [Hartshorn] in the Domesday Book