Arrhenotoky (from Greek -τόκος -tókos "birth of -" + ἄρρην árrhēn "male person"), also known as arrhenotokous parthenogenesis, is a form of parthenogenesis in which unfertilized eggs develop into males. In most cases, parthenogenesis produces exclusively female offspring, hence the distinction.

The set of processes included under the term arrhenotoky depends on the author:[1] arrhenotoky may be restricted to the production of males that are haploid (haplodiploidy); may include diploid males that permanently inactivate one set of chromosomes (parahaploidy); or may be used to cover all cases of males being produced by parthenogenesis (including such cases as aphids, where the males are XO diploids).[1] The form of parthenogenesis in which females develop from unfertilized eggs is known as thelytoky; when both males and females develop from unfertilized eggs, the term "deuterotoky" is used.[2]

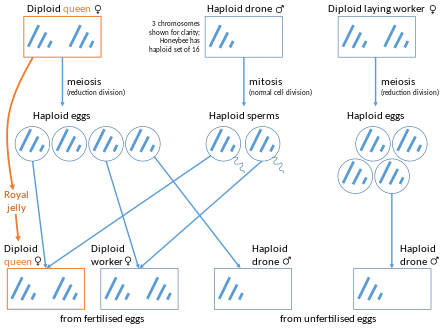

In the most commonly used sense of the term, arrhenotoky is synonymous with haploid arrhenotoky or haplodiploidy: the production of haploid males from unfertilized eggs in insects having a haplodiploid sex-determination system. Males are produced parthenogenetically, while diploid females are usually[a] produced biparentally from fertilized eggs. In a similar phenomenon, parthenogenetic diploid eggs develop into males by converting one set of their chromosomes to heterochromatin, thereby inactivating those chromosomes.[4] This is referred to as diploid arrhenotoky or parahaploidy.[5]

Arrhenotoky occurs in members of the insect order Hymenoptera (bees, ants, and wasps)[6] and the Thysanoptera (thrips).[7] The system also occurs sporadically in some spider mites, Hemiptera, Coleoptera (bark beetles), Scorpiones (Tityus metuendus) and rotifers.

See also edit

Notes edit

- ^ Unless in certain rare cases they too are produced by thelytokous parthenogenesis.[3]

References edit

- ^ a b Normark, B. B. (2003). "The evolution of alternative genetic systems in insects". Annual Review of Entomology. 48: 397–423. doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112703. PMID 12221039.

- ^ Gavrilov, I.A.; Kuznetsova, V.G. (2007). "On some terms used in the cytogenetics and reproductive biology of scale insects (Homoptera: Coccinea)" (PDF). Comparative Cytogenetics. 1 (2): 169–174. ISSN 1993-078X.

- ^ Pearcy, M.; Aron, S.; Doums, C.; Keller, L. (2004). "Conditional Use of Sex and Parthenogenesis for Worker and Queen Production in Ants". Science. 306 (5702): 1780–1783. Bibcode:2004Sci...306.1780P. doi:10.1126/science.1105453. PMID 15576621. S2CID 37558595.

- ^ Nur, U. (1972). "Diploid arrhenotoky and automictic thelytoky in soft scale insects (Lecaniidae: Coccoidea: Homoptera)". Chromosoma. 39 (4): 381–401. doi:10.1007/BF00326174. S2CID 23071909.

- ^ Nur, U. (1971). "Parthenogenesis in Coccids (Homoptera)". Integrative and Comparative Biology. 11 (2): 301–308. doi:10.1093/icb/11.2.301. JSTOR 3881755.

- ^ Grimaldi, David A.; Michael S. Engel (2005-05-16). Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press. p. 408. ISBN 9780521821490.

- ^ White, Michael J.D. (1984). "Chromosomal mechanisms in animal reproduction". Bolletino di Zoologia (free full text). 51 (1–2): 1–23. doi:10.1080/11250008409439455. ISSN 0373-4137.